A World Disjointed

China, Russia, and the Coming Era of Inter-imperialist Rivalry

November 3, 2025

doi.org/10.63478/FQIMWV2C

In This Feature

THE GLOBAL POLITICAL economic order is not just changing; it is out of joint. Most strikingly, the United States under the second Trump administration is partially dismantling the very foundations of its postwar global power.1Research for this article was supported by the Alameda Institute. Trump’s wrecking ball has targeted “soft power” institutions, such as USAID, Voice of America, and Radio Free Europe. Moreover, by consistently ceding ground to Putin and suggesting that Europe is largely on its own, Trump is changing the map of alliances that defined the US position during the postwar era.

There are also signs of retrenchment in other parts of the world: for example, the United States is reportedly considering scrapping the US Africa Command, reducing its military presence on the continent.2Courtney Kube and Gordon Lubold, “Trump Admin Considers Giving up NATO Command That Has Been American since Eisenhower,” NBC News, March 18, 2025.

The administration shut down the Millennium Challenge Corporation—an aid agency that invested primarily in Africa—and dismissed 1,350 State Department workers, 15 percent of its staff. Marco Rubio, the new secretary of state, declared the emergence of the “multipolar world,” seemingly implying that the US needs to rethink the goal of strategic primacy, that is, overarching global leadership.3“Secretary Marco Rubio with Megyn Kelly of The Megyn Kelly Show” (Interview), United States Department of State, January 30, 2025, tinyurl.com/bd63tdse.

In this alleged “multipolar world,” the United States remains in a uniquely powerful position. International Relations (IR) scholars Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth assert that “partial unipolarity” is a more apt description of the current international system.4Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Myth of Multipolarity: American Power’s Staying Power,” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 3 (2023): 76–91.

They cite continuing military dominance of the United States, especially the command of the commons (the air, open sea, and space), with China and Russia not even close to matching US supremacy. They also highlight the imperatives of technological authority: US companies account for 53 percent of the profits of the world’s top high-tech firms, while the share of the country’s closest competitors (China and Japan) is in the single digits.

To this we should add the continuing dominance of the US dollar. In January 2025, it accounted for 57 percent of global foreign exchange reserves, 54 percent of export invoicing, and 88 percent of foreign exchange transactions.55. “Dollar Dominance Monitor,” Atlantic Council, 2025, tinyurl.com/53kj4b2f. The dollar’s preeminence gives the United States a unique ability to inflict economic pain on other countries through financial sanctions. In effect, the US is not just one “pole” among many: it is by the most powerful country in the world. How do we square this extreme power imbalance with the “multipolar” vision of the Trump administration? What will this tension lead to?

The story of US hegemony, however, is complicated by one glaring weakness. While the United States has an undisputed military and financial lead, China is similarly dominant in manufacturing. Recently China has been identified as the world’s only manufacturing superpower: its global share of the gross manufacturing output (35 percent) is now higher than that of its ten closest competitors combined.6Richard Baldwin, “China Is the World’s Sole Manufacturing Superpower: A Line Sketch of the Rise,” VoxEU (CEPR), January 17, 2024.

In some strategically important industries, the gap is even wider. For example, China commands over 50 percent of global shipbuilding capacity while the US share is less than 1 percent. If the US–China relationship is indeed “the most important bilateral relationship in the 21st century” which “will determine the future of the world,” as Rubio claims, what does the radical asymmetry between the two countries (US military and financial dominance, Chinese manufacturing dominance) mean for their present and future relations?7“Wang Yi Has a Phone Call with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China (Minister’s Activities), January 24, 2025, fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbzhd/202501/t20250125_11545093.html.

The characteristic differences between countries are significant, but is it appropriate to view the organization of global capitalism in national terms to analyze the current conjuncture? Political theorists have argued that the emergence of the transnational capitalist class (TCC) renders obsolete any analysis that hinges on individual country characteristics (for example, China’s 35 percent share of global manufacturing and the United States’s 60 percent share of the global stock market).8William I. Robinson, Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107590250. According to the TCC school, the differing capabilities of the US and Chinese economies should not be seen as resources possessed by their respective national elites engaged in inter-imperialist rivalry, but rather as elements of functional specialization within the global accumulation regime organized by the class of transnational capitalists.

For this class, China is a manufacturing platform, and the United States is a financial center and consumer market. Yet in fact, the US and Chinese economies remain powerfully interconnected (far more than, say, British and German economies on the eve of the First World War). And yet the political elites of the two countries seem to be on an inexorable spiral of confrontation, with mutual trade and investment restrictions and other hostile measures. National politics refuses to give way to the transnational state serving the interests of trans-national capitalists, as suggested by the TCC school. Subsequently, how can we theorize the relationship between the national and the transnational in the current moment?

The world in 2025 is clearly very different from 1913, 1989, or even 2008. Historical analogies, as well as all-encompassing theories such as the TCC, illuminate only certain aspects of the current global conjuncture. The aim of this article is to provide a fresh analysis of global economic competition, one that builds on existing theoretical foundations but seeks to juxtapose different theories in critical and Marxist IR scholarship to produce a holistic picture of the current moment.

2025 is clearly very different from 1913, 1989, or even 2008. Historical analogies illuminate only certain aspects of the current global conjuncture.

With events such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Trump’s radical foreign policy shift, we are entering uncharted territory. The article focuses on China and Russia, their changing global position, the political and economic factors behind their relations with the United States and the rest of the world, and the articulation of the national and the transnational within their economies. The goal is to uncover the mechanics of the current inter-imperialist rivalry, its structural and subjective (ideological) factors and the scenarios for the future.

For socialists, the study of imperialism has always been a highly practical exercise. Our alliances and strategies are based on our theoretical understanding of the global imperialist conjuncture. Today, we are grappling with the multiplicity of imperialisms, which has been starkly revealed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, our current thinking about imperialism is still largely influenced by the late twentieth century unipolar moment. This article attempts to provide a theoretical basis for the new reality of global inter-imperialist rivalry.

How To Think about Major Non-Western Powers

There is a lively debate in critical and Marxist IR scholarship on the place and role of major non-Western powers, such as the original BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). One position, advanced by TCC theory, is that the BRICS economies are integrated into the global accumulation regime, and BRICS capitalists join the ranks of the TCC. Consequently, local state structures are reorganized so that they can act as nodes of the transnational state serving the interests of the TCC.9William I. Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS: A Global Capitalism Perspective,” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2015): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.976012.

This perspective acknowledges the role of the state; however, state power is expected to be deployed precisely to manage the integration of the BRICS economies into global capitalism. At best, local states may try to negotiate a wider space for “their” TCC contingents within the global accumulation regime, but the potential for geopolitical rivalries is generally downplayed within the TCC school.

Another perspective is that of subimperialism. Building on the insights of the Brazilian dependency theorist Ruy Mauro Marini, this perspective differs significantly in its approach from the TCC theory. The lens is national: BRICS states and capitalists are not seen as extensions of the transnational state and transnational capitalist class. Both political and economic elites in the BRICS countries are fundamentally dependent on the West. Their position is intermediate.

The political elites of the BRICS countries pursue “antagonistic cooperation” with the West, avoiding an all-out conflict while conducting assertive regional foreign policy. In turn, BRICS economic elites both depend on the Western centers of capital accumulation and export capital in their respective regions.10Patrick Bond, “Sub-Imperialism as Lubricant of Neoliberalism: South African ‘Deputy Sheriff’ Duty within BRICS,” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 2 (2013): 251–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.775783. In effect, BRICS countries act as regional “transmission belts” of global capitalism (which is ultimately anchored in the West), although they maintain significant autonomy in geopolitical and geoeconomic terms.

Finally, the geopolitical economy perspective emphasizes the autonomous role and agency of the state within (and possibly against) Western-led global capitalism. Like the subimperialism school, the lens is national: BRICS countries are seen as independent political and economic units.

Unlike the subimperialism perspective, the geopolitical economy school does not see political and economic dependence on the West as inevitable. BRICS countries can engage in state-led catch-up development, thereby improving the fortunes of national economies rather than transnational capital. In fact, they are already doing so, making the “multipolar world” a reality.11Radhika Desai, Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire (London: Pluto Press, 2013); Desai, “Geopolitical Economy: The Discipline of Multipolarity,” Valdai Papers 24 (2015): 1–12. According to a closely related heartland/contender theory, today’s contender states (most notably China) mobilize state power to coordinate their economies and counter the encroachment of the dominant Western capital.12Kees van der Pijl, “Is the East Still Red? The Contender State and Class Struggles in China,” Globalizations 9, no. 4 (2012): 503–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2012.699921.

There is strong empirical evidence to support all three perspectives. In line with the theoretical expectations of the TCC school, BRICS economies are closely intertwined with Western economies, BRICS capitalists are joining the interlocking global networks of ownership and control. Moreover, elements of BRICS state structures (such as central banks and economic ministries) are being reorganized to advance neoliberal globalization.

In turn, the strength of the subimperialism theory is the analysis of the BRICS’s multilateral institutions, which indeed largely act as “transmission belts” of Western-led global capitalism. For example, the New Development Bank, a BRICS institution, continues to make most of its loans in US dollars. A week into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the bank paused all transactions in Russia in line with US sanctions—despite Russia being one of its founding members. This vindicated Patrick Bond’s analysis of BRICS banking in terms of subimperialism.13Patrick Bond, “BRICS Banking and the Debate over Sub-Imperialism,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 611–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1128816.

Finally, the geopolitical economy perspective also has strong empirical support. BRICS countries have shown themselves capable of departing from the neoliberal agenda and implementing various protectionist and industrial policy measures to support their respective national capitals, sometimes at the expense of foreign firms. Defying the transnational state thesis, BRICS states continue to view the world in decidedly national terms, sometimes crafting their policy under the assumption of a zero–sum game between national economies (as opposed to their transnational integration).

The very success of all three theories in illuminating certain aspects of the BRICS economic and political development indicates that none of them can serve as an all-encompassing framework for analysis. The articulations of the national and the transnational vary in time and space—for example, China in the 2000s is quite different from Russia in the 2020s. Moreover, all three theories share a blind spot.

TCC theory—as promulgated by William Robinson—seemingly claims that all colonial and imperialist violence occurs on behalf of the TCC, be it the United States intervening in Iraq and Afghanistan, or Rwanda intervening in the Central African Republic and Mozambique.14William I. Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism, and Transnational Class Exploitation,” Science & Society 88, no. 3 (2024): 319–29, https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2024.88.3.319. The purpose of this violence is to expand and reinforce transnational capitalism.

Robinson does acknowledge that certain state policies, such as the reciprocal trade and investment restrictions between the United States and China, “undercut transnational capital integration.”15Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism,” 327. He goes on to claim that such policies contradict the interests of the TCC and their roots lie in the resurgent nationalism propagated by the political elites: “Make America Great Again! Make China Great Again! Make Russia Great Again!”16William I. Robinson, “The Travesty of ‘Anti-Imperialism,’” Journal of World-Systems Research 29, no. 2 (2023): 587–601, 598, https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2023.1221. In effect, Robinson’s theory of the state is simultaneously hyper-functionalist and entirely “autonomist.” States around the world are expected both to serve the interests of the TCC, regardless of the national context, and to act against the TCC’s wishes when local political elites are gripped by nationalist ideas.

Perhaps an easier way out of this conundrum is to relax the theoretical assumptions of TCC theory. Capital in the current moment has indeed achieved an unprecedented level of global integration, nevertheless, the concept of multiple nation-based capitals is not entirely outdated. Companies still identify with “their” countries and lobby their domestic governments to protect them from other nation-based capitals (which, in turn, lobby their own domestic governments).

The process of the TCC formation, both in terms of transnational ownership interlocks and the transnational “class consciousness” shaped by platforms such as the Davos Forum, is fragile and prone to reversal.17David Chen, “Rethinking Globalization and the Transnational Capitalist Class: China, the United States, and Twenty-First Century Imperialist Rivalry,” Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis 85, no. 1 (2021): 82–110, https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2021.85.1.82. We have to recognize the reality of inter-imperialist rivalries in which the national political and economic elites grow closer together (despite the latter’s tendency towards transnationalization).

The initial impulse might come from either the political or the economic elites (or a complex combination of the two), however, the very notion of an inter-imperialist rivalry as theorized by Lenin is not outdated as Robinson claims.18Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism,” 321. In effect, autonomous non-Western imperialism (which is not a manifestation of TCC interests) is entirely possible. Specific articulations of the national and the transnational across time and space represent an empirical question which should not be replaced by the axioms of any theory.

The subimperialism theory also suffers from a bit of an axiomatic blindness when it comes to non-Western imperialism. Patrick Bond has recently acknowledged that “a US relationship with a generally-reliable sub-imperial partner [China] could evolve into a far more serious inter-imperial rivalry, especially if Taiwan or South China Sea become sites of military competition.”19Patrick Bond, “After Johannesburg: BRICS+ Humbled as Sub- (Not Anti- or Inter-) Imperialists,” CounterPunch, August 31, 2023. He also acknowledged that Putin’s “invasion of Ukraine broke the rules of how far a regional gendarme was typically allowed to roam,” testifying to the “rogue character of subimperialism” in Putin’s Russia.20Bond, “After Johannesburg.”

In effect, Bond recognizes that China and Russia no longer fit into the subimperialist role. However, his theory cannot explain why Russia went rogue or why China’s rivalry with the United States went beyond the notion of “antagonistic cooperation”—precisely because Bond’s theory is based on the axiom that the BRICS states are subimperialist. Moreover, with Russia going rogue and China becoming too powerful to be the US’s junior partner, can we still say that other major non-Western states (Brazil, India, South Africa, Turkey) maintain sufficient levels of political and economic dependence on the US to warrant the label “subimperialism”? Perhaps the very hierarchy of imperialist–subimperialist formations is gradually becoming a thing of the past—a temporary artifact of the post–1989 “unipolar moment.”

The geopolitical economy school seems best suited to explain non-Western imperialism, as it postulates a high degree of autonomy from the West and close interlocking of political and economic elites in the BRICS contender states. However, this autonomy is seen as fundamentally defensive: “Contender states epitomize the defense of state sovereignty against the sovereignty of transnational capital championed by the West.”21Kees Van der Pijl, “The BRICS—An Involuntary Contender Bloc Under Attack,” Estudos Internacionais 5, no. 1 (2017): 25–46, 29, https://doi.org/10.5752/P.2317-773X.2017v5n1p25.

Imperialism is thus equated with the Western heartland, while contender states are portrayed as somehow escaping either the economic contradictions (such as overaccumulation of capital) or political trends (such as the rise of revanchist nationalism) that could turn them into imperialist actors going on the offensive, rather than merely defending themselves against the West. This omission (or, rather, deliberate rejection) of the very possibility of non-Western imperialism leads to rather tortured narratives where Russia’s decades-long imperialist aggression against Ukraine is portrayed as a “defense” against the (nonexistent) “NATO siege” of Russia.22Pijl, “The BRICS,” 26.

Resurgent Russian imperialism does not really fit into any of the existing theories.

In sum, despite the proliferation of critical analyses, there remains a curious theoretical vacuum on the left. In the most glaring example, resurgent Russian imperialism—whose existence by now could only be doubted by bad-faith actors—does not really fit into any of the three theories mentioned above. It is not an expression of the interests of the TCC, nor is it a regional power play within the framework of antagonistic cooperation with the West, nor a defense against the encroachment of Western imperialism.

In this article I do not intend to offer a new and comprehensive theory of non-Western imperialism. Instead, my aim is a conjunctural analysis that draws on, and benefits from, the juxtaposition of existing theories. I will begin with China and then move on to Russia.

China: The Power of National Capital

There is much evidence to support the TCC thesis in China’s economic development. By the mid–2000s, the Chinese economy had achieved an unprecedented level of integration with Western economies, particularly the United States, so that the “the scale of the financial transactions between the two halves [China and the US] was comparable with the flows that traditionally have occurred within nation states rather than between them.”23Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick, “‘Chimerica’ and the Global Asset Market Boom,” International Finance 10, no. 3 (2007): 215–39, 229, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2362.2007.00210.x.

The arrangement, described by Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick as “Chimerica,” involved China’s gigantic trade surplus with the US and the reinvestment of export profits in US public debt. This scheme boosted investment-driven manufacturing growth in China, debt-driven consumption growth in the United States and the corporate profits of transnational capital. It also created huge global imbalances, such as the wave of deindustrialization in the United States known as the China shock, and it depressed wages and consumption in China (the basis of its export competitiveness).24David H. Autor, David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” Annual Review of Economics 8, no. 1 (2016): 205–40, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080315-015041.

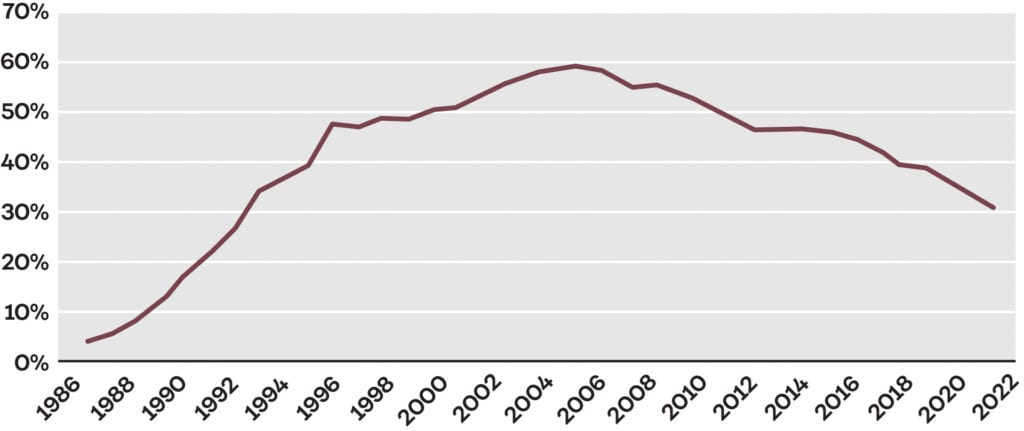

Figure 1: Imports and exports of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in China

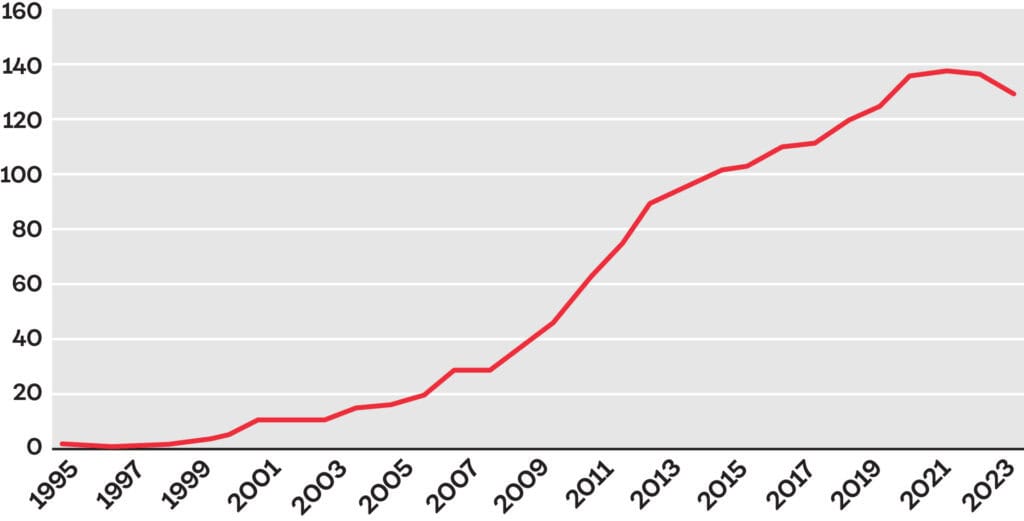

Initially, transnational capital in China was represented by Western companies moving production there. By the mid–2000s, foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) accounted for some 60 percent of Chinese imports and exports (Figure 1). However, export-led economic growth triggered the expansion of China’s own transnational corporations. The number of Chinese companies on the Fortune Global 500 list has risen steadily since the mid–2000s (Figure 2). By 2018, China overtook the United States as the country with the most companies on the list, only for the United States to regain the top spot in 2023.

Figure 2: Number of Chinese companies on the Fortune Global 500 list

TCC theorists would argue that the origins of transnational corporations do not matter because their ownership, control, and operations are highly globalized. But they clearly matter in the Chinese case as China’s largest businesses are simultaneously enmeshed in networks of transnational ties and networks of domestic political control. Chinese corporations (including state-owned enterprises) invest all over the world and invite foreigners, particularly from the West, to join their boards.

Moreover, a large segment of the Chinese business elite has economics and management degrees from Western universities.25Nana de Graaff, “China Inc. Goes Global: Transnational and National Networks of China’s Globalizing Business Elite,” Review of International Political Economy 27, no. 2 (2020): 208–33, 216, https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1675741. At the same time, Chinese state-owned enterprises are monitored and controlled by party and state institutions, with their top management nominated through the nomenclature system of appointments and receiving regular party training.26Nathan Sperber, “Servants of the State or Masters of Capital? Thinking through the Class Implications of State-Owned Capital,” Contemporary Politics 28, no. 3 (2022): 264–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2021.2022323.

Private businesses are bound to the state through the network of party cells (all of China’s five hundred largest private firms currently have them), as well as through public investment and joint ventures.27Jeffrey Becker, “Fused Together: The Chinese Communist Party Moves Inside China’s Private Sector,” In Depth, CNA September 6, 2024. Studies generally conclude that while Chinese companies have operational autonomy, the ultimate decision-making power rests with the party–state elites.28Naná de Graaff and Bastiaan van Apeldoorn, “US Elite Power and the Rise of ‘Statist’ Chinese Elites in Global Markets,” International Politics 54, no. 3 (2017): 338–55, 352, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0031-2.

In fact, the transnationalization of the Chinese economy was a strategic choice made by the country’s leadership rather than the result of lobbying by foreign or domestic capital. Adopting a “post-Listian” developmental strategy, the Chinese state sought to maximize national advantages within globalization rather than simply pursue autonomous development, as argued by Friedrich List in his 1841 treatise The Natural System of Political Economy.29Gerard Strange, “China’s Post-Listian Rise: Beyond Radical Globalisation Theory and the Political Economy of Neoliberal Hegemony,” New Political Economy 16, no. 5 (2011): 539–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.536210.

In practice, this translated into proactive engagement with international institutions such as the IMF and the WTO, as well as multiple measures to prioritize and support Chinese companies domestically, while taking full advantage of the opportunities created by foreign direct investment (FDI). The support for domestic (private and state) capital at the expense of FIEs has included the strategic use of antitrust law, intellectual property law, and product and technological standards; public procurement policies; and pressure on FIEs to engage in technology transfer.30Thomas A. Hemphill and George O. White, “China’s National Champions: The Evolution of a National Industrial Policy—Or a New Era of Economic Protectionism?” Thunderbird International Business Review 55, no. 2 (2013): 193–212, https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21535.

The “Made in China 2025” plan set specific targets for Chinese companies’ domestic and global market share in several key industries, unsurprisingly causing a stir in the West.31Max J. Zenglein and Anna Holzmann, “Evolving Made in China 2025: China’s Industrial Policy in the Quest for Global Tech Leadership,” MERICS Papers on China 8 (July 2019), 32. Far from acting as a node of the transnational state serving the interests of the TCC, the Chinese state revealed a vision of the global economy as a zero–sum competition between national capitals in which China and its corporations must win.

During the heyday of “Chimerica,” US corporations lobbied the US government to promote deeper economic integration with China, culminating in China’s ascension to the WTO in 2001. According to Ho-fung Hung, “Powerful American corporations were the glue, stabilizer, and fuel for the Chimerica formation.”32Ho-fung Hung, Clash of Empires: From “Chimerica” to the “New Cold War,” Elements in Global China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108895897. However, faced with China’s growing support for its own national capital, US corporations have increasingly advocated for a tougher stance on China, including tariffs, to pressure the Chinese government to reverse its course.

In January 2025, Jamie Dimon, the head of JPMorgan Chase—who was once a staunch opponent of protectionism—claimed that tariffs could be used to “bring people to the table.”33Rob Copeland, “In Shift, Jamie Dimon Backs Trump’s Tariffs, Saying ‘Get Over It,’” New York Times, January 22, 2025. A recent Financial Timesop-ed chastises US business for not doing enough to protect free trade multilateralism.34Alan Beattie, “Big Business Tries a Dangerous Dalliance with Populist Protectionists,” Financial Times, June 24, 2024. In fact, US corporations are adapting by bringing production back to the United States (a process known as reshoring) and taking advantage of the country’s resurgent industrial policy, such as the CHIPS act.35Noah Smith, “Yes, Reshoring American Industry Is Possible: Americans Can Make Stuff After All,” Noahpinion, January 24, 2025, noahpinion.blog/p/yes-reshoring-american-industry-is.

In response to the threat of Chinese capital fused with the party–state elites, US capital itself is being partially “nationalized” in its mode of accumulation as well as its relation to the US state. This trend is far from absolute, but it is observable. It seems that neither the TCC theory nor the heartland/contender theory, but rather the classic Leninist notion of an inter-imperialist rivalry between nation-based state–capital formations is increasingly applicable to the US–China relations.36By way of comparison: “Capitalist economic competition is an emergent property of multiple capitals seeking their self-expansion in conflict with other capitals. The efforts of multiple capitalist states to open different parts of the Global South to their ‘own’ transnational capital’s trade and investment comes in conflict with the efforts of other national capitalist states to secure access for ‘their’ transnationals. Particularly in periods of stagnant and declining profitability and exacerbated market competition, these state policies create the conditions for political-military rivalry among imperialist powers.” Charles Post, “Explaining Imperialism Today,” Spectre, no. 7 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.63478/81CQPIAU. This is Hung’s conclusion as well.37Hung, Clash of Empires, 65. See also Chen, “Rethinking Globalization.”

The major difference with the Anglo–German rivalry before the First World War is the much more interdependent character of the US and Chinese economies. Elements of “Chimerica” are still in place. China’s trade surplus with the United States was $361 billion in 2024, more than a third of its total surplus of almost $1 trillion.38Dian Zhang, “US–China Trade Deficit Grew in December as Potential Tariffs Loomed,” USA Today, January 15, 2025. In the same year, China held $1.8 trillion of US securities, including $1 trillion of US public debt, second only to Japan.39Karen M. Sutter, “US–China Trade Relations,” In Focus, IF1124 Version 32, Congressional Research Service Reports and Issue Briefs, April 11, 2025, congress.gov/crs-product/IF11284.

Until recently, this combination of rivalry and interdependence resulted in limited but gradually escalating conflict. Prior to Trump’s second election, neither side wanted to pull the trigger on a “hard” decoupling that would have cost both countries trillions of dollars in the long run.40Daniel Rosen and Lauren Gloudeman, “Understanding US–China Decoupling: Macro Trends and Industry Impacts” (Report), Rhodium Group, February 17, 2021, rhg.com/research/us-china-decoupling/. Instead, the conflict took the form of targeted, reciprocal moves to establish centrality in global infrastructure, digital, production, and finance networks.41Seth Schindler et al., “The Second Cold War: US–China Competition for Centrality in Infrastructure, Digital, Production, and Finance Networks,” Geopolitics 29, no. 4 (2024): 1083–120, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432.

This struggle for network centrality did not imply exclusive territorial control over the two countries’ “spheres of influence,” which was characteristic of the original Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. As a result, competing visions of national capitalist development could actually produce mutual benefits on the ground in specific countries.

A study of the Belt and Road Initiative in Egypt found that Chinese investment in infrastructure has filled the gap left by Western states, making Egypt more attractive for Western investment (which has indeed outstripped Chinese investment in recent years).42Yahya Gülseven, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative and South–South Cooperation,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 25, no. 1 (2023): 102–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2022.2129321. In other words, the United States and China may not have converged on the transnational state, but their rivalry could be productive for global capitalism.

With Trump’s tariff war, however, a hard decoupling could indeed become a reality. At the time of writing, both countries have imposed massive tariffs on each other. The outcome of this conflict remains to be seen.

There are other reasons, both structural and agency-related, to expect the US–China rivalry to intensify in the future, possibly in unpredictable directions. Structural factors include the contradictions of Chinese capitalism. As noted in the introduction, China currently accounts for 35 percent of global manufacturing output. To maintain high growth rates, the country’s leadership intends to double down on industrial exports, potentially increasing China’s share of global manufacturing even further—at the expense of other countries.

There are other reasons to expect the US–China rivalry to intensify in the future, in unpredictable directions.

With the United States and Europe turning to protectionism, only the developing world can absorb China’s rising industrial output. This has led to speculation about a possible “China Shock 2.0,” this time in developing countries.43Jason Douglas, John Emont and Samantha Pearson, “China’s Flood of Cheap Goods Is Angering Its Allies, Too,” Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2024. Katia Dmitrieva Philip Heijmans and Prima Wirayani, “A New ‘China Shock’ Is Destroying Jobs Around the World,” Bloomberg, March 19, 2025. With the Global South erecting its own barriers against Chinese exports, China could resort to coercion, weaponizing existing economic ties to seek expanded market access. Alternatively, it could increase manufacturing FDI instead of supplies of finished goods, using developing countries as a platform to sustain exports to the West. This contradicts Western efforts to securitize their supply chains against undue Chinese influence.44Camille Boullenois and Charles Austin Jordan, “How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies” (Note),

Rhodium Group, June 18, 2024, rhg.com/research/how-chinas-overcapacity-holds-back-emerging-economies/.

In sum, Chinese overcapacity and overaccumulation of capital could lead it to adopt more coercive (that is, imperialist) behavior in the Global South, thus sharpening an inter-imperialist rivalry with the West over the influence in the developing world. Glimpses of the future could be seen in Indonesia’s criticism of cheap Chinese exports and plans to introduce tariffs on certain Chinese goods—plans that were scrapped after a sharp rebuke by the Chinese Foreign Ministry.45Douglas, Emont and Pearson, “China’s Flood.” The United States can then pose as the region’s protector against “China’s coercive and unfair trade policies,” as Rubio put it after a meeting with the Japanese and South Korean foreign ministers, even as the United States strongarms its “partners” with new tariffs.46Secretary Marco Rubio’s post in full reads: “It’s not that complicated: China threatens our security and prosperity. At today’s meeting with the Indo-Pacific partners, we agreed the region needs to be free from China’s coercive and unfair trade policies. Our security depends on it” (@SecRubio, X, April 3, 2025).

Economic contradictions are superimposed on geopolitical tensions. This is where the situation is most unpredictable. Taiwan remains a flashpoint. There is not much we can say about China’s possible use of force against Taiwan that would not amount to mere speculation (apparently a favorite pastime of the US commentariat when it comes to Taiwan). One thing that is certain is Taiwan’s crucial importance for Xi’s ideological vision of “national rejuvenation,” as he himself emphasized in multiple speeches.47“Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Speech at First Session of 14th NPC,” Xinhua, March 14, 2023; “China’s Xi Calls for Taiwan Reunification on Eve of National Day,” Voice of America, September 30, 2024.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine demonstrates that the independent causal role of ideology should not sbe discounted. Another certainty, however, is the exceedingly difficult nature of an invasion or naval blockade of Taiwan from a military standpoint.48David Sacks, “Why China Would Struggle to Invade Taiwan,”

Council on Foreign Relations, June 12, 2024, cfr.org/article/why-china-would-struggle-invade-taiwan. Here, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might be relevant for China’s leadership as an example of unwarranted war optimism.

A similar uncertainty exists in the United States. The second Trump administration includes China hawks such as Rubio and Elbridge Colby, recently nominated as the undersecretary of defense for policy. Colby has long argued for prioritizing United States involvement in the Indo-Pacific at the expense of Europe and the Middle East, and specifically for ramping up the defense of Taiwan. For Colby, the island’s defense is crucial to prevent Chinese hegemony over the entire region, which would prove disastrous for the United States in terms of economic development and, ultimately, national security.49Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021). (Of course, such a strategy might provoke China just as well as it could deter it.)

However, it is not entirely clear whether Trump himself shares this approach. It is possible that he might seek some kind of “grand deal” with China, handing over Taiwan in exchange for China’s economic withdrawal from the Western Hemisphere. In this territorial vision of “spheres of influence,” Russia will advance further West (it will be up to Europe to stop it), China will have greater control in the Indo-Pacific, and the United States will be the undisputed economic and political master of the Western Hemisphere in a new edition of the Monroe Doctrine.

Whether such “territorialization” of inter-imperialist rivalries is compatible with the very nature of modern globalized capitalism is an open question. However, given Trump’s propensity to make grandiose, system-shattering decisions, and to deploy his sovereignty in radical ways (which makes him like Putin), the possibility of such a neo-imperial redivision of the world cannot be dismissed.

Russia: A Neofascist Moment

Russia’s story is in many ways like China’s. Under Putin, the transnationalization of the Russian economy was combined with an active role for the state: another version of “post-Listian” developmentalism, or integrated state capitalism.50Matthew D. Stephen, “Rising Powers, Global Capitalism and Liberal Global Governance: A Historical Materialist Account of the BRICs Challenge,” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 4 (2014): 912–38, 914, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066114523655. Which is to say, a state capitalist formation that exploits the benefits of globalization and actively renegotiates the place of “its” national capital within the global accumulation regime.

In the Russian context, this has also been referred to as “sovereign globalization.”51Nigel Gould-Davies, “Russia’s Sovereign Globalization: Rise, Fall and Future,” Policy Commons, January 6, 2016, policycommons.net/artifacts/1423383/russias-sovereign-globalization/2037652/. Like Chinese capital, Russian capital had “two faces”: it was enmeshed simultaneously in networks of transnational ties and networks of domestic political control.52de Graaff, “China Inc.” Russia’s largest businessmen, or “oligarchs,” as they came to be colloquially known (despite Putin expropriating their direct political power), invested all over the world, set up joint ventures with foreign transnational companies and, in their personal capacity, acquired real estate in places like London and Miami, sending their children to elite private schools there.

And yet they never fully merged with the TCC for the same reason that Chinese capitalists did not: they remained tied to the Russian state through various formal and, above all, informal channels. Moreover, Putin significantly expanded the state sector, partially reversing the privatization wave of the 1990s, with state capital engaging in transnationalization but also remaining under explicit government control as well as Putin’s personal informal control through patron–client relationships with state managers.

A key difference, however, is that unlike Chinese protectionism and industrial policy, Russian protectionism and industrial policy did not really threaten Western centers of capital accumulation for the simple reason that the Russian economy was, and remains, much smaller and less diversified than China’s.

Moreover, on balance, the global integration of the Russian economy brought significant benefits for Western capital. The latter made huge profits from Russian commodity exports, even as the Russian state sometimes unilaterally renegotiated the terms of this relationship by, for example, pushing the Western consortium led by Royal Dutch Shell to sell a majority stake in the joint venture Sakhalin–2 (an oil and gas field in the Russian Far East) in 2006. Even Russian imperialism could be seen as profitable for Western capital.

When Gazprom pressured post-Soviet states to pay more for gas by temporarily cutting off supplies, it was the company’s Western investors such as BlackRock, not just the Russian state, that benefited. Up until 2014, Russia acted as a subimperialist formation, expanding the reach of global capitalism in the post-Soviet region, including through coercive means.

There were certainly economic tensions with the West in a small number of areas where Russia had the most market power, for example, in the natural gas trade with the European Union. However, they proved manageable, as evidenced by new projects such as Nord Stream 2, launched in 2011. Moreover, these tensions were rooted less in economic competition between national capitals and more in geopolitical issues (concerns over Europe’s growing dependence on Russian gas, and therefore, the Kremlin’s will).

Finally, the Russian political elites’ mode of engagement with transnationalization was only partially developmentalist and, in significant ways, kleptocratic. The chief goal of the Kremlin was not always the expansion of the influence of national capital and its advancement on the global value chain. Instead, Russian political elites relied on transnational ties for rent-seeking and personal enrichment.

For example, Putin directly benefited from Russian oil exports through Gunvor, a Swiss-based trading company that used to be partially owned by Gennady Timchenko, one of the businessmen who served as managers of Putin’s personal wealth53.Tom Miles, “US Sanctions Hit Gunvor Co-Founder, Prompting Stake Sale,” Reuters, March 21, 2014. Western capital was only too happy to accommodate for this form of transnationalization by providing legal, public relations and other services to the elements of the Russian economic elites which were directly tied to the Kremlin. Such “kleptocratic transnationalism” was certainly not a threat to Western centers of capital accumulation.

Nevertheless—and this is a second crucial difference with China—the Kremlin has done something that US and Chinese elites have been reluctant to do, at least until recently: it has pulled the trigger on a hard decoupling from the West by invading Ukraine in 2022. The slide began in 2014 with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and covert invasion of Eastern Ukraine which resulted in the first wave of sanctions and the reduction of ties with Western capital.

The Kremlin has done something that the US and Chinese elites have been reluctant to do: pulled the trigger on a hard decoupling from the West.

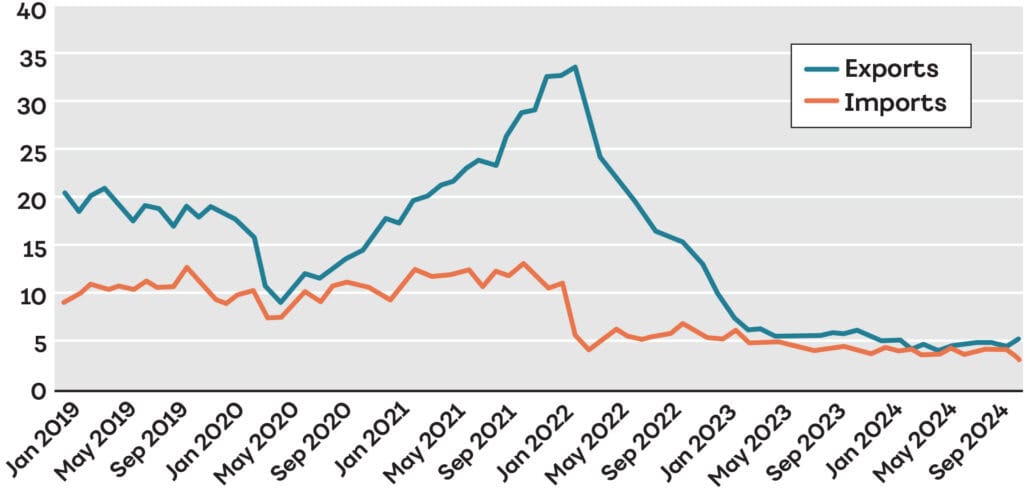

Figure 3: Russian trade with EU 27, US, UK, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland and Norway

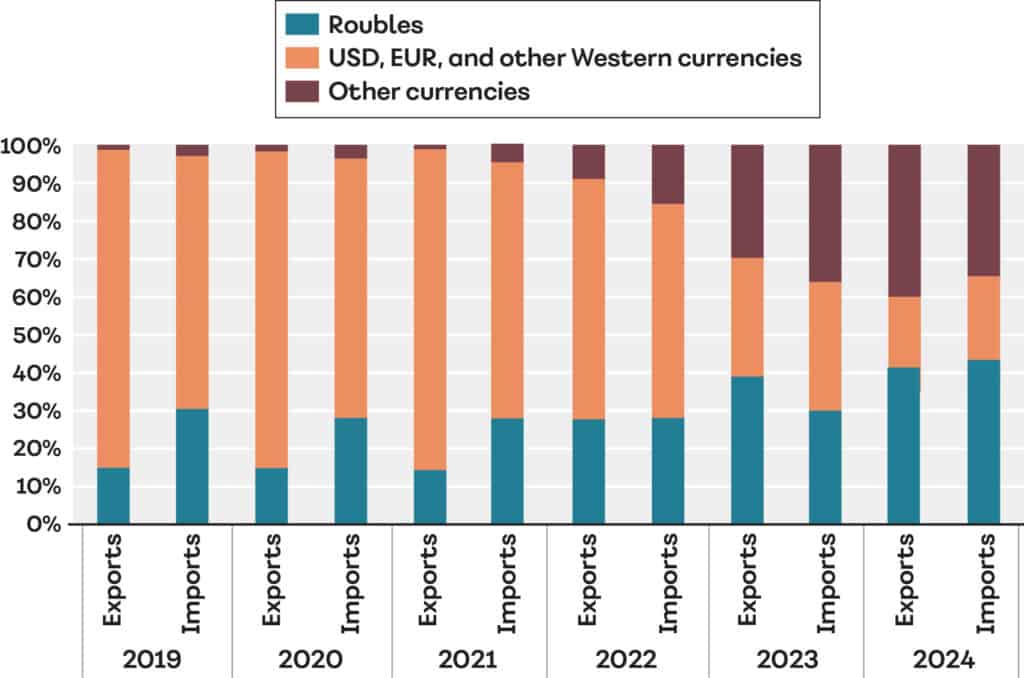

Following the full-scale attack on Ukraine in 2022, the dollar- and euro-denominated reserves of the Russian central bank were frozen, trade and investment ties collapsed (after a short spike in Russian exports due to a crisis on the European natural gas market), and Russian capital largely lost control over its Western assets (Figure 3). Moreover, the Russian economy has by necessity de-dollarized, with trade in rubles and non-Western currencies (primarily Chinese yuan) steadily growing since 2022 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Currencies used in Russian exports and imports

The roots of Russia’s hard decoupling from the West lie in Putin’s sovereign decisions. Structural, long-term factors play a much smaller role in this conflict than in the US–China rivalry. As mentioned above, Russian capital has never been a threat to the Western centers of capital accumulation. Moreover, geopolitically, the West, and the United States in particular, have been quite accommodating of Russia’s security concerns, despite the Kremlin’s (and some Western leftists’) rhetoric to the contrary.

As NATO has expanded eastward, European armies have become smaller and less capable than they were during the Cold War. Moreover, US troops have been steadily withdrawing from Europe, from a peak of three hundred thousand in the 1980s to around thirty thousand in the mid–2010s.54Scott Boston et al., “Assessing the Conventional Force Imbalance in Europe: Implications for Countering Russian Local Superiority,” RAND, Research Report, February 5, 2018, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2402. Determined to reap the “peace dividend,” Western countries have significantly reduced their military footprint on the European continent. There were tensions with Russia around strategic stability and nuclear deterrence, but they too proved manageable, with the United States modifying its European missile defense plan at Russia’s request.55David M. Herszenhorn and Michael R. Gordon, “US Cancels Part of Missile Defense That Russia Opposed,” New York Times, March 17, 2013.

Nevertheless, Putin’s persistent sense of vulnerability to Western-orchestrated “regime change” led him to take drastic action in Ukraine in 2014. He imagined the Maidan uprising as part of a global plot to install compliant governments through “color revolutions” (which he saw as coup attempts instigated by Western intelligence agencies), and a rehearsal for such a “revolution” in Russia itself. This paranoid, conspiracist worldview, shared by Putin and his KGB-trained entourage, was the factor that ultimately tipped the scales from “antagonistic cooperation” to radical confrontation with the West.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine since 2014 (or rather since 2013, when the Kremlin put enormous pressure on the Yanukovych government to join the Russian-led Eurasian Customs Union) has unsurprisingly been counterproductive, further alienating Ukrainians and pushing Western governments to adopt a more hostile stance towards Russia. To salvage the situation in Ukraine while resigning himself to a complete break between Russia and the West (which he saw as inevitable anyway), Putin launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The Russian economy survived the decoupling from the West due to a combination of three factors. First, Russia proved to have some structural power in a few industries where its exports were an important part of global trade, notably crude oil, agricultural products, and fertilizer.

It was impossible to eject Russia from these markets without causing a global upheaval, which influenced the calculations of the Biden administration and other Western powers. As a result, Russian crude was targeted by limited sanctions (a price cap of $60 per barrel, poorly enforced and high enough to ensure the profitability of the Russian oil industry), while agricultural products and fertilizer were not sanctioned at all.

Second, Russia relied on trade with non-Western countries, especially China, which now accounts for a third of Russian imports and exports. An industrial powerhouse, China has been able to replace most Western exports to Russia. Finally, military mobilization of the economy ensured very low unemployment rates (2.4 percent in January 2024) and surging output in military-related sectors.

The Russian case forces us to rethink various strands of critical scholarship on major non-Western states. The TCC and subimperialism theories illuminate certain aspects of Russia’s post-Soviet development, including the growth of ties with Western capital and generally cooperative, if tense, relations with the United States and other Western countries in the pre–2014 period. However, Russia’s post–2014 trajectory does not fit either of these two theories.

The geopolitical economy perspective is not helpful either, since it too ultimately revolves around the West, although it sees non-Western states as capable of “protecting” themselves from the encroachment of Atlantic capital. Russia, however, has not protected itself from the West, but has developed its own sui generis imperialism, going on the offensive in the post-Soviet region, as well as in Africa and the Middle East.

Finally, the classic Leninist notion of inter-imperialist rivalry is also of limited use when applied to contemporary Russia, since economic contradictions have been secondary in driving Russia’s confrontation with the West. While Russia does not fit neatly into any of these theories, it should be seen as a historically specific case of imperialism: an imperialist actor led by a narrow, ideologically motivated set of political elites with a dictator at the helm; a state operating on the principle of “primacy of politics,” that is, the logic of forcing economic elites to adapt to the sovereign decisions of the ruler and their consequences; a securitized economy, “fortress Russia,” partly self-sufficient and constantly adjusting its external economic relations.

All this points to a variant of neofascism. As a neofascist formation, Russia both reacts to and causes global changes, shattering the remnants of capitalist globalization and the “rules-based international order.”

Taking Stock

The world’s attention is understandably locked on the United States under the second Trump administration. The speed with which economic and foreign policy orthodoxies are being smashed is indeed breathtaking. But the transformation of the Western-led global political and economic order has been long in the making.

In this article, I have focused on the two countries that have contributed most to this transformation. China developed a powerful national capital that is merged with the party–state elites, expands globally in search of “spatial fixes” and forces Western capital to turn to “its own” nation-states for help.56David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). In this way, the emerging transnational capitalist networks have partly “renationalized,” paving the way for protectionism and industrial policy in the Western heartland.

The speed is breathtaking, but the transformation of the Western-led global political and economic order has been long in the making.

Russia, on the other hand, has forced a decoupling from the West by attacking Ukraine. The size of Russia’s economy, its possession of the world’s largest nuclear arsenal and the ideational power of the Kremlin’s neofascist ideology beyond Russia’s borders ensure that the global consequences of Russia’s “rogue act,” as Patrick Bond put it, will be profound. At the very least, they include Europe’s massive remilitarization to counter the Russian threat.

Trump’s radicalism is ultimately a response, however disjointed and irrational, to global changes that are largely driven by China and Russia. And yet, the new US position and strategy remain unclear. Will it really force a complete decoupling from China? Will it embrace a territorial vision of inter-imperialist rivalry, going as far as annexing territories in the Western Hemisphere? Will it critically undermine the role of the dollar as a reserve currency? How will the US military presence in key regions of the world—Africa, the Middle East, the Indo-Pacific and the Arctic—change? At this point, we can only guess. What’s important is that it’s not just Trump’s decisions that will determine the outcome but the domestic and global reactions to them.

In a world facing the revenge of the nation-state (which includes the fracturing of transnational capitalist ties, the spread of protectionism, and the rise of right-wing nationalist ideologies), the theories of the TCC, subimperialism, and geopolitical economy require a profound reevaluation. A historical materialist attention to the structural pressures and contradictions of global capitalism remains a basis for such a reappraisal (and has indeed made it possible to identify a deep cause of the US–China rivalry).

However, the potency of the sovereign agency of political elites (and individual leaders) should not be discarded, especially in the context of right-wing, neofascist formations such as Trump’s United States and Putin’s Russia, where the heightened role of sovereign decision-making is “built into” the very political project of Trumpism and Putinism. An analysis that successfully integrates structure and agency, political economy, and ideology will allow for a better understanding of the current moment—and ultimately a more effective political response to it. ×

Notes & References

- Research for this article was supported by the Alameda Institute.

- Courtney Kube and Gordon Lubold, “Trump Admin Considers Giving up NATO Command That Has Been American since Eisenhower,” NBC News, March 18, 2025.

- “Secretary Marco Rubio with Megyn Kelly of The Megyn Kelly Show” (Interview), United States Department of State, January 30, 2025, tinyurl.com/bd63tdse.

- Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Myth of Multipolarity: American Power’s Staying Power,” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 3 (2023): 76–91.

- “Dollar Dominance Monitor,” Atlantic Council, 2025, tinyurl.com/53kj4b2f.

- Richard Baldwin, “China Is the World’s Sole Manufacturing Superpower: A Line Sketch of the Rise,” VoxEU (CEPR), January 17, 2024.

- “Wang Yi Has a Phone Call with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China (Minister’s Activities), January 24, 2025, fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbzhd/202501/t20250125_11545093.html.

- William I. Robinson, Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107590250.

- William I. Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS: A Global Capitalism Perspective,” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2015): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.976012.

- Patrick Bond, “Sub-Imperialism as Lubricant of Neoliberalism: South African ‘Deputy Sheriff’ Duty within BRICS,” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 2 (2013): 251–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.775783.

- Radhika Desai, Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire (London: Pluto Press, 2013); Desai, “Geopolitical Economy: The Discipline of Multipolarity,” Valdai Papers 24 (2015): 1–12.

- Kees van der Pijl, “Is the East Still Red? The Contender State and Class Struggles in China,” Globalizations 9, no. 4 (2012): 503–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2012.699921.

- Patrick Bond, “BRICS Banking and the Debate over Sub-Imperialism,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 611–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1128816.

- William I. Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism, and Transnational Class Exploitation,” Science & Society 88, no. 3 (2024): 319–29, https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2024.88.3.319.

- Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism,” 327.

- William I. Robinson, “The Travesty of ‘Anti-Imperialism,’” Journal of World-Systems Research 29, no. 2 (2023): 587–601, 598, https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2023.1221.

- David Chen, “Rethinking Globalization and the Transnational Capitalist Class: China, the United States, and Twenty-First Century Imperialist Rivalry,” Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis85, no. 1 (2021): 82–110, https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2021.85.1.82.

- Robinson, “Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism,” 321.

- Patrick Bond, “After Johannesburg: BRICS+ Humbled as Sub- (Not Anti- or Inter-) Imperialists,” CounterPunch, August 31, 2023.

- Bond, “After Johannesburg.”

- Kees Van der Pijl, “The BRICS—An Involuntary Contender Bloc Under Attack,” Estudos Internacionais 5, no. 1 (2017): 25–46, 29, https://doi.org/10.5752/P.2317-773X.2017v5n1p25.

- Pijl, “The BRICS,” 26.

- Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick, “‘Chimerica’ and the Global Asset Market Boom,” International Finance 10, no. 3 (2007): 215–39, 229, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2362.2007.00210.x.

- David H. Autor, David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” Annual Review of Economics 8, no. 1 (2016): 205–40, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080315-015041.

- Nana de Graaff, “China Inc. Goes Global: Transnational and National Networks of China’s Globalizing Business Elite,” Review of International Political Economy 27, no. 2 (2020): 208–33, 216, https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1675741.

- Nathan Sperber, “Servants of the State or Masters of Capital? Thinking through the Class Implications of State-Owned Capital,” Contemporary Politics 28, no. 3 (2022): 264–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2021.2022323.

- Jeffrey Becker, “Fused Together: The Chinese Communist Party Moves Inside China’s Private Sector,” In Depth, CNA September 6, 2024.

- Naná de Graaff and Bastiaan van Apeldoorn, “US Elite Power and the Rise of ‘Statist’ Chinese Elites in Global Markets,” International Politics 54, no. 3 (2017): 338–55, 352, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0031-2.

- Gerard Strange, “China’s Post-Listian Rise: Beyond Radical Globalisation Theory and the Political Economy of Neoliberal Hegemony,” New Political Economy 16, no. 5 (2011): 539–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.536210.

- Thomas A. Hemphill and George O. White, “China’s National Champions: The Evolution of a National Industrial Policy—Or a New Era of Economic Protectionism?” Thunderbird International Business Review 55, no. 2 (2013): 193–212, https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21535.

- Max J. Zenglein and Anna Holzmann, “Evolving Made in China 2025: China’s Industrial Policy in the Quest for Global Tech Leadership,” MERICS Papers on China 8 (July 2019), 32.

- Ho-fung Hung, Clash of Empires: From “Chimerica” to the “New Cold War,” Elements in Global China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108895897.

- Rob Copeland, “In Shift, Jamie Dimon Backs Trump’s Tariffs, Saying ‘Get Over It,’” New York Times, January 22, 2025.

- Alan Beattie, “Big Business Tries a Dangerous Dalliance with Populist Protectionists,” Financial Times, June 24, 2024.

- Noah Smith, “Yes, Reshoring American Industry Is Possible: Americans Can Make Stuff After All,” Noahpinion, January 24, 2025, noahpinion.blog/p/yes-reshoring-american-industry-is.

- By way of comparison: “Capitalist economic competition is an emergent property of multiple capitals seeking their self-expansion in conflict with other capitals. The efforts of multiple capitalist states to open different parts of the Global South to their ‘own’ transnational capital’s trade and investment comes in conflict with the efforts of other national capitalist states to secure access for ‘their’ transnationals. Particularly in periods of stagnant and declining profitability and exacerbated market competition, these state policies create the conditions for political-military rivalry among imperialist powers” (Charles Post, “Explaining Imperialism Today,” Spectre, no. 7 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.63478/81CQPIAU.

- Hung, Clash of Empires, 65. See also Chen, “Rethinking Globalization.”

- Dian Zhang, “US–China Trade Deficit Grew in December as Potential Tariffs Loomed,” USA Today, January 15, 2025.

- Karen M. Sutter, “US–China Trade Relations,” In Focus, IF1124 Version 32, Congressional Research Service Reports and Issue Briefs, April 11, 2025, congress.gov/crs-product/IF11284.

- Daniel Rosen and Lauren Gloudeman, “Understanding US–China Decoupling: Macro Trends and Industry Impacts” (Report), Rhodium Group, February 17, 2021, rhg.com/research/us-china-decoupling/.

- Seth Schindler et al., “The Second Cold War: US–China Competition for Centrality in Infrastructure, Digital, Production, and Finance Networks,” Geopolitics 29, no. 4 (2024): 1083–120, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432.

- Yahya Gülseven, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative and South–South Cooperation,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 25, no. 1 (2023): 102–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2022.2129321.

- Jason Douglas, John Emont and Samantha Pearson, “China’s Flood of Cheap Goods Is Angering Its Allies, Too,” Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2024. Katia Dmitrieva Philip Heijmans and Prima Wirayani, “A New ‘China Shock’ Is Destroying Jobs Around the World,” Bloomberg, March 19, 2025.

- Camille Boullenois and Charles Austin Jordan, “How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies” (Note),

Rhodium Group, June 18, 2024, rhg.com/research/how-chinas-overcapacity-holds-back-emerging-economies/. - Douglas, Emont and Pearson, “China’s Flood.”

- Secretary Marco Rubio’s post in full reads: “It’s not that complicated: China threatens our security and prosperity. At today’s meeting with the Indo-Pacific partners, we agreed the region needs to be free from China’s coercive and unfair trade policies. Our security depends on it” (@SecRubio, X, April 3, 2025).

- “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Speech at First Session of 14th NPC,” Xinhua, March 14, 2023; “China’s Xi Calls for Taiwan Reunification on Eve of National Day,” Voice of America, September 30, 2024.

- David Sacks, “Why China Would Struggle to Invade Taiwan,”

Council on Foreign Relations, June 12, 2024, cfr.org/article/why-china-would-struggle-invade-taiwan. - Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021).

- Matthew D. Stephen, “Rising Powers, Global Capitalism and Liberal Global Governance: A Historical Materialist Account of the BRICs Challenge,” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 4 (2014): 912–38, 914, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066114523655.

- Nigel Gould-Davies, “Russia’s Sovereign Globalization: Rise, Fall and Future,” Policy Commons, January 6, 2016, policycommons.net/artifacts/1423383/russias-sovereign-globalization/2037652/.

- de Graaff, “China Inc.”

- Tom Miles, “US Sanctions Hit Gunvor Co-Founder, Prompting Stake Sale,” Reuters, March 21, 2014.

- Scott Boston et al., “Assessing the Conventional Force Imbalance in Europe: Implications for Countering Russian Local Superiority,” RAND, Research Report, February 5, 2018, rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2402.html, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2402.

- David M. Herszenhorn and Michael R. Gordon, “US Cancels Part of Missile Defense That Russia Opposed,” New York Times, March 17, 2013.

- David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).