Class Revenge Fanfiction

Imagination Against Capitalism

October 14, 2025

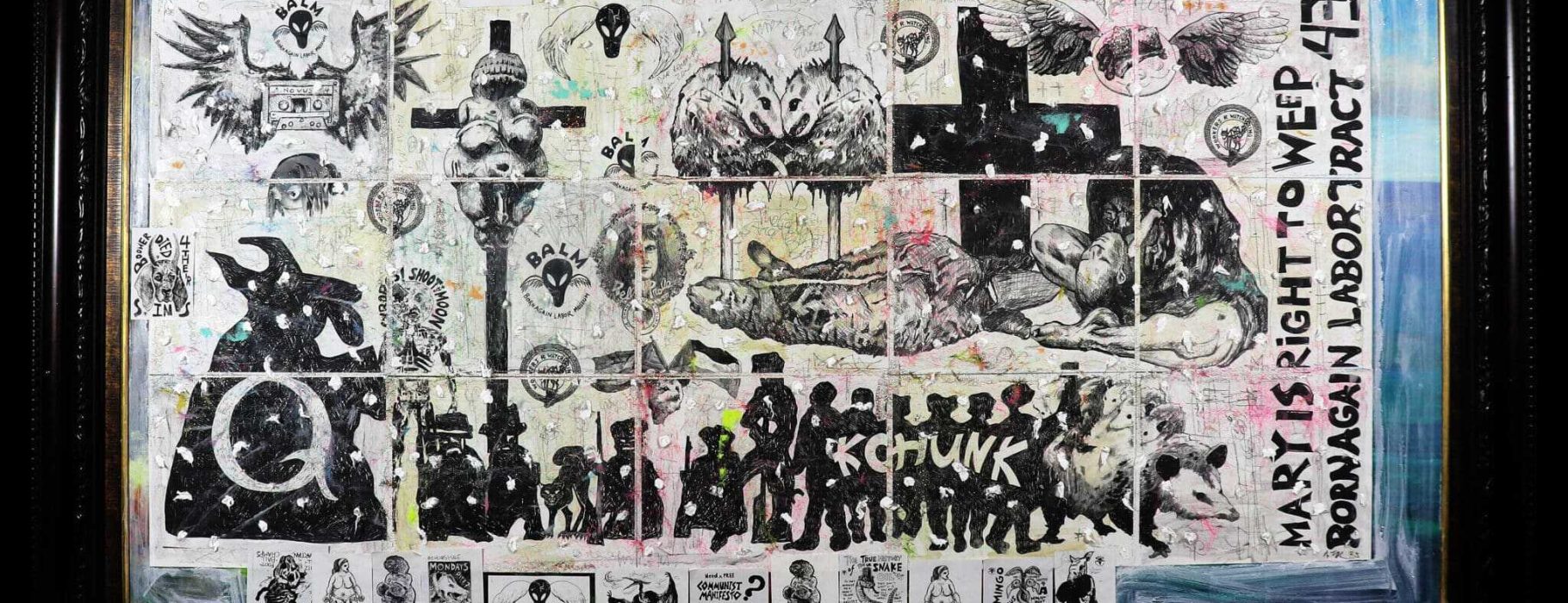

Thanks to both Adam Turl and Anupam Roy for allowing us to use their artwork for this piece.

Fanfiction

Fanfiction, at its core, is an act of narrative rebellion—a form of storytelling born from dissatisfaction, from the refusal to accept the endings and limitations handed down by dominant culture. It is a mode of narrative revenge. When fans write alternative endings, insert new characters, remix timelines, or imagine crossover worlds, they are responding to an absence—a failure of the original text to represent their desires, identities, politics, or truths. Fanfiction says, implicitly and explicitly, “This story is incomplete. This story, in the way it has been offered, is not for me.” It creates something new, that challenges, disrupts, and refuses the official canon.

It can summon deferred and repressed queerness, as with the T. Jonesy and Killa video “What if They Hadn’t Made it to Vulcan in Time?” which mixed footage of Star Trek’s Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and Spock (Leonard Nimoy), accompanied by Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer.”1“Star Trek + Nine Inch Nails = Closer,” YouTube video, posted by “alexanderadb,” September 8, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uxTpyCdriY. Fanfiction can undo or subvert racist tropes. It can undo the passivity of the cultural recipient and allow them to intervene, for good or bad, within the canons of narrative franchises—Harry Potter, Star Wars, Marvel, Supernatural, Star Trek, and so on. These franchises have become mythologies, offering so many contemporary stories for how to live in and navigate the world. Notable exceptions aside, the official canons tend to be shaped by the ideologies and economies of racialized and heterosexist capitalism.

If fanfiction is narrative revenge against canon, then capitalism itself is the original failed canon. We live inside a story structured by accumulation, denial, and exploitation—a story that teaches us that our place is to work and endure. It tells us, if we’re “fortunate,” we may hope that our children might endure just a little less. This is capitalism’s three-act tragedy: you will labor ceaselessly, you will suffer in silence, and your descendants might inherit a slightly softened version of your pain. It’s a brutal story that insists on conformity, resignation, and quiet desperation. Class-revenge fanfiction (CRFF) is an interruption to that narrative arc—moments of rupture and insurgency that challenge the inevitability of suffering and erasure.

Working-Class Fanfiction

What would it look like if the working class got to rewrite the story? This is a question that fuels the urgency behind CRFF. It is a form of storytelling born from frustration and the suffocating narrowness of capitalist narratives that dictate who gets to speak, dream, and survive in the stories we consume. The goal is to represent lives that feel familiar, aspirational, and inspirational to working-class people. These are stories for us, stories that do not reduce us to passive recipients of suffering or mere victims of circumstance. Instead, they defy suffering. They refuse the tired, sanitized plots that ask us to endure quietly, be grateful for crumbs, and passively wait for salvation. They let pain fracture the floor beneath us, revealing the unsettling realities of what it means to live, resist, and break under capitalism. CRFF articulates stories rooted in the concrete realities of working-class life—the exhaustion, precarity, dignity, humor, rage—but refuse to be shackled by the limits of capitalist realism or capitalism’s narrow moral arcs. These narratives do not aim to simply document existence but disrupt it.

This means borrowing from various irrealist traditions—speculative fiction, science-fiction, surrealism—including absurdism. As noted in the first Locust Review editorial:

Our irrealism must be, at punctuated moments, absurdist. The contemporary invocation of absurdism is an assertion of tricksterism. This is a representation of how a precarious working-class experiences events as cosmic randomness: 9/11 and the “War on Terror”, the economic collapse of 2008, the rise of Trump, the vagaries of online mobs in a world in which every online person has become a public figure, the sudden growth of socialist organization in the U.S., etc. Or, more prosaically, the sudden loss of health insurance, employment, housing, a sudden death at the hands of the police, the sudden demise of a bourgeois politician caught in a pedophilia ring. In this cosmic random variable lies hope as well as tragedy. The trickster is not good or evil. It is creation and destruction. This is not to say the aforementioned events are truly cosmic or random. They can be explained by Marxism and science. However, they are often experienced in a manner that recalls the randomness of everyday life…2Editorial, “We Demand an End to Capitalist Realism,” Locust Review 1 (2019), 2, https://www.locustreview.com/editorial/we-demand-an-end-to-capitalist-realism.

In my short story “Sewerbot,” originally published by Red Wedge Magazine, a working-class robot is dumped into the city sewer by the megacorporation that created it.3Tish Markley (Turl), “Sewerbot,” Red Wedge, May 1, 2019, https://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/sewerbot. The robot claws and climbs through filth and slime, shooting upward towards the “meat”—a grotesque, rich, smug class of consumers perched safely above the muck. In capitalism, “realism” often becomes a language of resignation and tacit acceptance. In this way, realism smooths over contradiction and discomfort, insisting that status quo is itself a kind of verisimilitude. Absurdity, by contrast, opens a space for contradiction, for grief and laughter to coexist. Absurdity can expose the grotesque logic beneath the surface. The Zurich Dadaists during the First World War used nonsense and chaos as antiwar protest, rejecting the logic that led to mass slaughter. The Situationists staged détournements—subversive reappropriations of spectacle that twisted consumer culture back onto itself. “Sewerbot” is rage made mechanical, the embodiment of labor stripped of humanity, given a voice through glitch, malfunction, and scream. The robot’s journey is a reminder that, under capitalism, rebellion is messy, broken, and incomplete.

What I want is rupture—a narrative break so sharp it unsettles complacency. I want revenge, but not the revenge sold by Hollywood’s action flicks, where catharsis is a bullet and justice is a scoreboard. I mean revenge as political and emotional reckoning. Revenge as the imaginative reclaiming of narratives we have been denied, silenced from, or made to internalize as self-defeating.

Revenge, Reclamation, and Insurgent Form

I’m not talking about cinematic swagger or glamorized violence. This revenge is more complex. It’s a political impulse that simmers and boils over after years of exploitation and privation. It’s the return of the repressed. This revenge is a kind of accountability; it creates spaces where representation is not a performance of obedience or an appeal to the bourgeois oversoul, but defiance and assertion of presence. Consider the myth of Cassandra, condemned to prophesy truth but never be believed. What if, instead of silence, she screamed louder until the walls themselves trembled? Or Medea, who commits acts deemed monstrous, not out of cruelty but desperation and rupture with her circumstances. These figures can become emotional embodiments of refusal. I draw from this lineage: female, queer, othered, racialized, and marginalized characters who have nothing left to lose and who refuse to keep quiet.

Fanfiction proper wasn’t designed to be respectable or polished. Its élan vital comes from its origins in the margins, at the intersections of genre, identity, class, gender, sexuality, and culture. Fanfiction is queer by nature; it is excessive, emotional, and designed for imagining alternative possibilities, insisting that the original ending was not good enough. This energy is what makes fanfiction a vessel for class revenge. It uses familiar cultural tools—tropes, archetypes, genre conventions, settings—to create subversion rather than mere replication. In this way it echoes, with proletarian instinct and genius more than historical memory, Brechtian alienation and disruption.4Bertolt Brecht argued for the use of traditional tropes in theater, as well as disruptions to said tropes, to create both an emotional response as well as a critical reflection during his plays. This was called estrangement or the alienation effect. The theorist Darko Suvin applied this idea to science fiction. He argued that science fiction created a “cognitive estrangement” in the reader by contrasting the rationality of science to the irrationality of capitalist society. China Miéville argued that it was not the scientific aspect of the genre that created estrangement, but the irreal or speculative nature of the stories themselves. What allowed for criticality was not the scientific, but the speculative nature of the stories read against capitalist ideology. Michael Löwy argued that irrealism more generally had this critical potential. The interventionist nature of fanfiction, however, sets it apart. See Bertolt Brecht, “A Short Organum for the Theatre,” in Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, ed. J. Willet (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992); Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (Peter Lang AG, 2016), https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0353-0735-1; China Miéville, “Cognition As Ideology: A Dialectic of SF Theory,” in Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction (Pluto, 2009); Michael Löwy, “The Current of Critical Irrealism: A Moonlit Enchanted Night,” in Adventures in Realism, ed. Matthew Beaumont (Blackwell, 2007), doi.org/10.1002/9780470692035.ch11. The disrupted canon is, in part, the everyday: the grocery store’s fluorescent hum, the temp job’s relentless monotony, the cold gaze of the surveillance camera, bodily exhaustion after a double shift, bus routes that trace the city’s veins, basement breakrooms where quiet conversations ferment rebellion. Here, we can stage revolt with narratives that unsettle the accepted scripts of capitalist life.

Fan Labor and the Politics of Inclusion

Fanfiction, for many of us, was never really just a hobby, but a contradictory insurgency before we even had the language for revolt. In her critique of structural whiteness in fandom and fan studies, Rukmini Pande writes, “My introduction to fan fiction was…eye-opening, as I could interrogate my notions of gender and sexuality in ways that were not a topic of discussion in my home. For a very long time, I didn’t feel the need to bring my own particularly ‘Indian’ forms of fandom into these spaces, as my engagement with them was on different terms, compartmentalized neatly in my head as ‘not suitable.’”5Rukmini Pande, “Naming Whiteness: Interrogating Fan Studies Methodologies,” in A Fan Studies Primer: Method, Research, Ethics, ed. Paul Booth and Rebecca Williams (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2021), 43, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv20dsbvz.6. These digital commons—the fanfiction spaces of the earlier, more anarchist Internet—offered a kind of freedom, albeit still restrained by ideology. That freedom was bounded by structural whiteness, class assumptions, and cultural legibility. The question wasn’t just who gets to speak, but what forms of speech were marked as “suitable,” “marketable,” or “legible” to an imagined default reader: white, middle-class, Western.

What’s true of fandom’s cultural space is also true of its mixed volunteer and paid labor economy. Kristina Busse describes fan labor as “particularly vulnerable to being co-opted…because by its very nature, it is based on and driven by love and passion. In fact, when we think about spreadability, fan labor is often explicitly the labor of loving and then sharing that love, an action Mel Stanfill terms lovebor.”6Kristina Busse, “Fan Labor and Feminism: Capitalizing on the Fannish Labor of Love,” Cinema Journal 54, no. 3 (2015):113–14, https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2015.0034. That love—whether for a world, a character, or a story—can become the rationale for non-compensation, invisibility, and exploitation. It’s the same emotional logic that capitalism uses to dismiss caregiving, teaching, the arts, and other feminized labor: if you’re doing it out of love, you should expect no reward. It is the cultural logic of social reproduction more generally.

Speculative fiction isn’t just about reflecting the world; it’s about prototyping worlds that don’t yet exist, worlds that refuse the capitalist present and imagine alternatives. Stories are a form of praxis: they are experiments in imagining different modes of existence and collective being, tools to dream the horizon of revolutionary transformation. The point is not simply to map the political unconscious, but to change it.

CRFF, however, doesn’t aim to be absorbed into capital. It is not sending its scripts to producers in hopes of a credit line. It refuses polish and gratitude. It refuses to convert care into content. It centers combustion over catharsis—stories that resist reification, because at the center of each is a guillotine. At the same time, revolt isn’t saved for a climactic denouement—it’s scattered like grit and glitter through every scene. A character pockets office supplies, smears the breakroom camera, screams into a karaoke mic at a wellness retreat. These aren’t grand gestures. They’re micro-defections. They reject the emotional discipline—the stoicism, patience, and performance of being a “team player”—that capitalism demands from workers.Where capitalist storytelling asks us to find dignity in endurance, CRFF understands that dignity lives in pushing the boot off your neck. The protagonist might not win, but they fuck up the algorithm. They crash the server. In CRFF, refusal becomes form.

Rebellious Protagonists

Let me illustrate by introducing some of my other protagonists, born from fragments of rage, loneliness, defiance, and desire. They don’t serve as moral exemplars or heroes with tidy arcs. Instead, they act out and refuse to behave. Their stories are rooted in the real, but pulse with speculative energy.

- AVI: A genderqueer cleaner in my novel-in-progresss, Sound. They spend their days scrubbing conference rooms and bathrooms they’ll never have access to beyond the service entrance—an “invisible” presence in buildings they can’t afford to enter as a guest. By night, they become a clandestine organizer, orchestrating acts of sabotage, including breaking locks, shattering cameras, and “misplacing” digital records. They fail often, but persist, not out of hope for immediate victory, but because the alternative of suffering alone and watching others suffer alone is unbearable.

- ERL: An itinerant myco-communist from Stink Ape Resurrection Primer, an ongoing prosimetrum published in Locust Review. They traverse the ruins of collapsed infrastructure, deploying spores of sentient fungi that form shared networks linking dissidents across borders in a kind of neural commons. They are not a hero. They are a medium, a spore-host facilitating a collectivized intelligence that dissolves the logic of state and capitalist control. These fungi remember what the authorities try desperately to erase. They become living archives of resistance and connection; a proxy for the Leninist “memory of the class.”

- GLAPIR: A limbless “snorg-snake from the Stink Ape prosimetrum who becomes a viral folk hero after eating a fascist city councilor on a livestream. They are immediately fired, denounced, and memed into caricature. But their story refuses to disappear. Children chalk their image on sidewalks and stoops. Street art, pins, and jokes carry their legend. Their initial act itself was unscripted and unstrategic. But that’s why it spreads, rippling through the city’s cracks and inspiring quiet defiance.

- CERO: An infiltrator of a virtual reality metaverse bar dominated by megalandlords and troll swarms. Armed with a laser-gun mod, she blasts every avatar she encounters, knowing full well it won’t stop the relentless rent hikes. But her actions change the tone—they make the powerful feel vulnerable, unsettled, exposed to the same daily fears and anxieties the less well-heeled endure. Her rebellion is cyclical: she gets banned, returns under new names, each loop a small disruption, a refusal to disappear.

- ALY: A preface writer in a Kafkaesque bureaucracy where nothing happens unless justified in poetic form. She pens moving, beautiful appeals supporting tax hikes, deportations, and budget cuts until she realizes the system depends entirely on her labor to make its cruelty palatable. Slowly, she begins to insert sabotage into footnotes—“typos” that are actually blueprints, “clarifications” that twist meanings until they unravel the entire logic of the bureaucracy.

Each of these characters is personal to me, embodiments of emotional (perhaps ecstatic) truth. They do not teach lessons. They insist that the world is a scam, that the stories we’ve been fed are lies and it’s time to write new ones that imagine new futures born of insurgency and revolt.

Kill the Critic in Your Head

There was a time when every word I wrote felt like walking a tightrope over a pit of judgment, self-censorship, and internalized pressure. The internal critic was capitalism in disguise.It echoed the voice of my mother. I found automatic writing—a practice you write without the interference of the conscious, rational mind. I stopped editing as I wrote. I let the strangest, ugliest, most unruly parts of my brain spill out without shame or hesitation. Automatic writing was pioneered by the Surrealists, who sought to unlock the unconscious and disrupt the “rational” order.7Automatic writing was popularized as a practice by the Surrealists, who combined anticapitalist politics with a focus on individual and collective psychology, as well as anti-imperialism. Feminist poets have used it as a tool of resistance, political dissidents as a means of survival, and psychic mediums as a bridge to the unknown. It short-circuited the critic lodged in my head. Failure in this framework is not the opposite of success; it is a refusal to play the capitalist game on its own terms. As I wrote in the poem, “Giving Up,”

I remember the first time I chose to give up

I was in the middle of a sentence,

Handing a customer their change,

Which scattered to the floor in a festive jingle,

And I decided to be finished with this bullshit.8Tish Turl, “Giving Up,” Locust Review 5 (2021), https://www.locustreview.com/online/giving-up.

Archives of the Unwritten

Fanfiction is often dismissed as mere escapism. A frivolous distraction from the “real” work of politics and survival. But there is a crucial distinction to be made between escapism that soothes and offers temporary refuge, and the failures, absurdities, and insurgent forms of narrative rupture that break dominant stories. Escapism comforts; rupture unsettles. It interrupts. It disrupts the scripts laid down by power, class, and ideology. Octavia’s Brood, the anthology edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, helped me grasp speculative fiction’s radical potential. It’s not simply fantasy, it’s rehearsal.9Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, eds., Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements (Oakland: AK Press, 2015). Rehearsal for feeling otherwise, for risking otherwise, for building otherwise. Speculative fiction isn’t just about reflecting the world; it’s about prototyping worlds that don’t yet exist, worlds that refuse the capitalist present and imagine alternatives. Stories are a form of praxis: they are experiments in imagining different modes of existence and collective being, tools to dream the horizon of revolutionary transformation. The point is not simply to map the political unconscious, but to change it.10Joseph North, Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History (Harvard University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2018.1550624.

If fanfiction is narrative revenge against canon, then capitalism itself is the original failed canon.

As Mark Fisher famously noted, capitalism has so thoroughly saturated our culture and consciousness that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism itself.11Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009). This nihilistic resignation is a form of ideological closure that kills hope and stifles imagination. CRFF pushes back against this closure. It insists something else is possible. Online fan communities can embody this insurgent possibility on a micro scale. They may have the potential to function as postcapitalist infrastructure in miniature—decentralized, cooperative, abundant. They can be sites of mutual aid, cultural production, and emotional sustenance, where people remix, respond, and uplift each other’s voices. In a society organized by (false) scarcity and competition, fan communities create surplus: surplus meaning, joy, representation, and care. They can build archives of unmet need, stories of invisibility and erasure, records of experience that capitalism refuses to recognize or commodify. They write not for profit, but because they must—because these stories are lifelines, vital threads in the fabric of survival and resistance. Fanfiction shouts back at the world: if the story hurts you, change it. If you’re not in it, insert yourself. If it kills you off, bring yourself back. adrienne maree brown captures this beautifully: “We have to imagine beyond…fears. We have to ideate—imagine and conceive—together.”12adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chico: AK Press, 2017), 14.

Sparks, Not Blueprints and Marxist Threads

So, what do these stories do? What power do they hold? They do not offer ready-made solutions or neatly packaged utopias. They do not provide blueprints to follow, nor do they always make tidy sense. They spark. They shift the mood, fracture silence, and make rage legible. They whisper: You are not wrong to want to scream. You are not wrong to want to destroy what is destroying you. You don’t need permission to imagine. You don’t need permission to revolt. Fanfiction taught me that someone always goes first, not because they are special, but because they must. That first rupture, that first refusal, is an act of courage and necessity. And then others follow. That is how uprisings begin. How stories multiply. How we claw our way out of silence and invisibility. Insurgent protagonists are not just metaphors for labor and rage, they’ve stopped waiting for permission. Neither should we.

This CRFF project is not just an aesthetic practice; it is a political one, grounded in a Marxist tradition of reading culture as a terrain of struggle. It is a rejection of capitalist realism, of imposed narrative closure, and of the ideological infrastructure that capitalism builds around our imaginations. When we write about robots dumped into sewers, rage-possessed spores, or bureaucrats who sabotage systems with poetry, we participate in what Antonio Gramsci would call a war of position—a slow, accumulative struggle over the terrain of culture and common sense.13Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, ed. and trans. Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 12–13, 245–46. Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony reminds us that ruling classes do not maintain power through coercion alone, but through the shaping of consciousness by dominant ideologies that feel so natural, so obvious, that they are rarely questioned. The narratives we consume (and are often consumed by) under capitalism reinforce a hegemonic order in which suffering is individualized, success is meritocratic, and alternatives to capitalism are not only impossible, but unthinkable. CRFF is an attempt to tear holes in this consensus reality. The characters I’ve created—Avi, Erl, Glapir, Cero, Aly—are counterhegemonic agents. They are, in Gramsci’s terms, models of organic intellectuals, emerging not from elite institutions but from the rhythms of labor and refusal. They speak with glitching circuits, spores, memes, and subtextual sabotage.

Fanfiction communities themselves have the potential to embody this Gramscian ideal. These are cultural spaces where nondominant groups (queer people, women, neurodivergent folks, BIPOC writers, disabled creatives, and working-class people) rewrite the script. Online archives like AO3 or smaller Discord collectives can be understood as microcosms of a potential counterhegemonic infrastructure—spaces where the logic of competition, productivity, and profitability is temporarily suspended. They teach us that what’s legible, desirable, or even realistic is not neutral, it is constructed, and therefore,can be deconstructed and replaced. CRFF is a structure of feeling, to borrow Raymond Williams’s formulation, the messy, excessive and unmarketable that resists full articulation in dominant ideological frameworks.14Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 132–33.

Just as Gramsci called for a “national-popular” culture rooted in the lives and languages of the people, capable of countering bourgeois cultural hegemony, these stories are an attempt to create a class-popular form of literature. A literature not designed to be approved by the gatekeepers of publishing or the academic literary canon, but one that speaks directly to the lived conditions of those scraping, surviving, rebelling. A literature where the grocery store becomes mythic terrain. When I describe these narratives as insurgent, when I invoke revenge as a mode of storytelling, I’m not talking about nihilism. I’m talking about a mode of becoming—an imaginative praxis that refuses capitalist narrative closure and insists on rupture. Marx tells us that “the ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.”15Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (New York: International Publishers, 2001), 27. My goal is to dethrone those ideas one glitch, one footnote, one broken sentence at a time. To write under capitalism is to write against forgetting, against the slow violence of invisibility and the brutal erasure of working-class, queer, disabled, racialized lives. CRFF is not a genre but a method. It emerges from the pressure points of everyday life, where exhaustion meets imagination. To embrace fanfiction as an insurgent form is to challenge the architecture of narrative under capital.