From Nepantla to Aztlán

Chicano Internationalism and the Struggle Against ICE

November 4, 2025

FOR MORE THAN SIXTY DAYS, Los Angeles has been under military occupation by federal agencies, the National Guard, and the Marines. By June 10, there were more active National Guard and Marine personnel deployed in LA than in Iraq and Syria combined.1Matthew Rozsa, “Trump Has Deployed More Troops in LA Than Syria and Iraq,” Truthout, June 2025. This overwhelming show of force came weeks after White House advisor—and notorious hatemonger—Stephen Miller, berated Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and ICE leadership over unacceptably low arrest numbers. Miller ordered officials to redirect raids toward Home Depot parking lots and 7–Eleven convenience stores to meet a daily quota of three thousand arrests.2Ginger Adams Otis and Robert Barba, “The White House Marching Orders That Sparked the LA Migrant Crackdown,” Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2025.

What is unfolding in Los Angeles is not an ordinary campaign of immigration enforcement but rather a desperate right-wing offensive whose unstated aim is to arrest political, cultural, and demographic shifts that supposedly threaten white supremacy. In fact, within the broader context of white supremacist panics of population replacement, Trump’s mass deportations are the beginning of a campaign of ethnic cleansing targeting undocumented migrant workers and the citizenship of Chicanos and others of Latin American descent.

What is unfolding in Los Angeles is not a campaign of immigration enforcement but rather a desperate right-wing offensive.

In truth, Los Angeles has never been a safe haven for white supremacy, and that terrifies men like Trump and Miller because they cannot claim ideological victory here. As Maga Miranda puts it, “Los Angeles stands as a constant reminder of the incomplete nature of the settler colonial project.” Unable to win outright, they shift tactics: “their aim instead is to brutalize and terrorize the population into compliance.”

What we are witnessing is not just repression, it is Stephen Miller’s revenge. “To be more precise,” Miranda concludes, “what is taking place now is a retaliatory campaign—a punishment for Los Angeles’s defiance and a message to every city that dares to resist Trump’s ethnonationalist agenda.”3Maga Miranda, “Defend the LAnd,” Spectre (online), June 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.63478/1UZ20PI3.

Nevertheless, Chicano formations, immigrant rights organizations, and social justice activists in Los Angeles and beyond have been working to advocate for the international working class since before the first Trump administration. By the time of Trump’s second inauguration, immigrant and social justice organizations had already established the basis for community patrols and rapid response networks (RRN) in the barrios.

These networks of thousands of volunteers have been mobilized by organizations of various political tendencies. Among these we find reformist immigrant advocacy organizations beholden to the Democratic Party like the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights Los Angeles (CHIRLA). Other organizations like Unión del Barrio (UdB), a Chicano organization based in the barrios, and the National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON) stand out within the rapid response networks, having trained and mobilized the most volunteers at this stage of the fight.

Unión del Barrio was founded in 1981 in Barrio Logan, San Diego, by activists from several Chicano groups. Since the 1980s it has fought against racism and police violence in the barrios and has organized for education and self-determination for Chicanos in the inner city. Its members identify as socialist anti-imperialists who embrace Indigenous struggles across the world through “raza internationalism” with the aim of creating a reunified revolutionary socialist México and Nuestra América.4“Ours Is a National Liberation Movement Rooted in Class Struggle—We Are Raza Internationalists,” Unión del Barrio, August 14, 2025, tinyurl.com/5bzxhnte. This record has brought police surveillance, as well as lawsuits against their members in the United Teachers Los Angeles in which they are accused of antisemitism for expressing solidarity with Palestinian liberation.5Glenn Sacks, “Anti-Union Group Deploys False Allegations of ‘Antisemitism’ to Attack UTLA,” Los Angeles Daily News, August 13, 2025.

One of the main organizations coordinating this movement work is the Community Coalition Self-Defense Coalition (CSDC), which is led by UdB and composed of more than seventy organizations that embrace self-defense strategies to protect working-class communities. The appropriation of self-defense language is deliberate since it’s clear that our communities and organizations are under attack. For example, most recently, organizations like CHIRLA, UdB, and the Party for Socialism and Liberation have been accused by Senator Josh Hawley, chair of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Counterterrorism, with specious charges of bankrolling “civil unrest.”6Josh Hawley, “GOP Senator Accuses LA Immigrant Rights Group of Aiding ‘Unlawful’ Acts During Ongoing ICE Protests,” LAist, June 11, 2025.

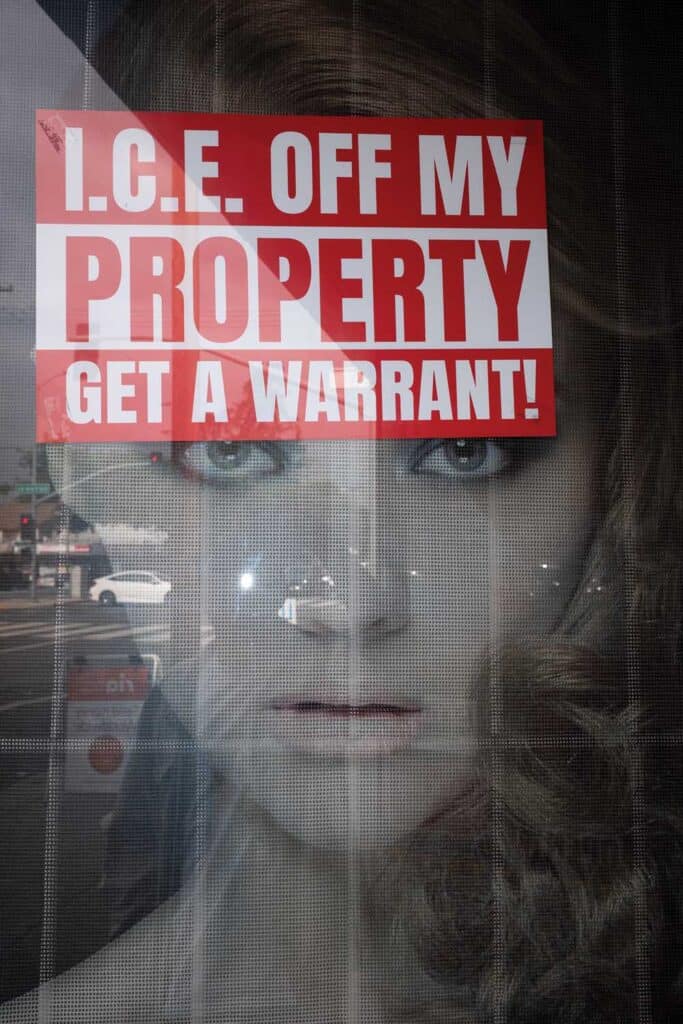

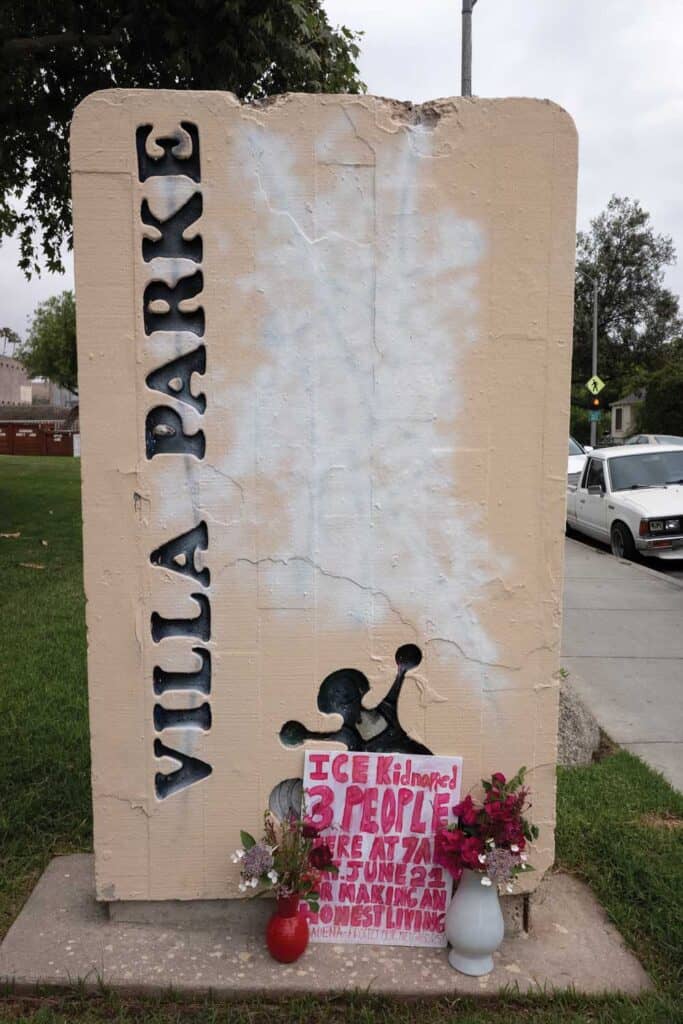

In response to ICE’s campaign of terror, the CSDC has helped to mobilize, train, and deploy thousands of volunteers across LA County and beyond. For example, the CSDC prepares teams of volunteers in the early hours of the morning to intercept ICE and DHS agents as they stage for an arrest. Fierce activists follow and harass ICE flunkies as they try to make arrests, warning communities about ICE patrols and reminding people of their rights. It is not an exaggeration to say that these tactics have saved thousands of people from deportation and have also lowered the morale of ICE agents.7Kelly Rissman, “Inside the ICE Offices Where Morale Is ‘Miserable’ and the Pressure Is High,” Independent, July 11, 2025.

Education organizations like the Association of Raza Educators (ARE) have also mobilized across the city to protect students. ARE was started in San Diego by members of UdB in 1994 at the height of the struggle against the racist Proposition 187 which aimed to establish a state-run citizen screening system and to prohibit undocumented people from accessing public education and other services in California. Since its inception, ARE has mobilized its members and allies through critical pedagogy and democratic education. As a result, they have been leaders in developing Ethnic Studies curriculum and establishing it in high school education across California.

Over the summer, ARE members have been training teachers in K–12 schools and community members to defend students and communities. For example, they conduct training to recruit volunteers for “ICE-watch” activities in schools and for community patrols in the barrios with the rapid response network. Predictably, as the fall 2025 semester began, ICE agents detained a student with disabilities outside Arleta High School, after “mistaking” him for someone else.

In response to pressure from educators, the district superintendent has asked for schools to become “no enforcement zones.” This demand will likely be ignored by ICE, and students, teachers, parents, and district workers will have to organize with ARE to restrict attacks on students.

Not all volunteers are on the front lines confronting ICE thugs. Many are connected to the movement through social media and online chats that monitor almost every incursion of ICE on organized communities. These volunteers organize visible presence through Self Defense Corners or Adopt a Day Laborer Corner initiatives to support day laborers and make their presence of the RRN known in our communities.

Another creative strategy has been the No Sleep for ICE campaign which targets hotels that host ICE and federal agents with protests in the early mornings and evenings. These types of actions have extended protests into the night and, in most cases, federal agents have had to check out of hotels after hours of noisy protests. While this surge of grassroots activism has been able to resist this campaign of terror and defend migrant communities, the overwhelming force that has been unleashed marks a turning point in immigration policy and American society.

ICE Raids are the Cutting Edge of Ethnic Cleansing

White supremacists like Stephen Miller and publications such as American Renaissance are explicitly obsessed with demographic shifts, and they interpret the growing nonwhite population as an existential threat. Emails obtained and released by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2019 reveal Miller’s repeated citations of white nationalist literature, including Camp of the Saints and articles from VDare, along with laments over the abolition of the 1924 Johnson–Reed Act and praise for early twentieth century race-based immigration policies as a model to emulate.8“Stephen Miller,” Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d., tinyurl.com/3wuudd79.

Miller consistently conflates immigration with the so-called “replacement” of white Americans by nonwhite groups, echoing the central premise of Great Replacement ideology9.Jason Wilson, “Leaked Emails Reveal Trump Aide Stephen Miller’s White Nationalist Views,” Guardian, November 14, 2019. These emails also revealed Miller’s collaboration with neo-Nazi Richard Spencer, as well as with Steve Bannon, who has regularly depicted Latino immigration as an “invasion.”10“Stephen Miller.”/mfn] These views have become calls to arms for white supremacists from Charlottesville where, in 2017, racists marched shouting “Jews Will Not Replace Us!” through the 2018 Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburg and up to the 2019 Walmart shooting in El Paso, Texas. Now that the far right is in power, the US state has engaged in a low intensity conflict with the population to enact its authoritarian agenda by targeting dissidents, including transgender people, federal workers, undocumented migrants, and pro-Palestinian activists.

As this conflict intensifies, we can’t ignore its parallels with Israel’s genocidal campaign underway in Gaza and the West Bank. Recently, Noura Erakat called attention to this process in her Boston Review article, “The Boomerang Comes Back,” arguing that “Palestine is not the exception, it is the laboratory.”10Noura Erakat, “The Boomerang Comes Back,” Boston Review, February 5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.63478/GU3ZD2QU.

In his 1950 polemic, Discourse on Colonialism, the Martinican writer observed what he called the “boomerang effect”: the brutality that imperial powers unleash on colonized peoples eventually returns home to corrode the core of the empire itself. As Erakat notes, the US-funded genocide in Gaza has ushered the return of Donald Trump to power, and “some seventy-five years later, Césaire’s point has been borne out many times over: there is no clear dividing line between a colonial power’s imperial geography and its metropole.”

In the US, just like in Israel, administrative detention without trial, predictive policing of neighborhoods, surveillance of activists, and preemptive criminalization are standard operating procedures. Thousands of Palestinians are imprisoned for being Palestinian or for where they live, and they disappear into legal black holes. Let’s not forget that the Palestinian–American student Mahmoud Khalil, for example, was detained by ICE for his participation in the student occupations against the genocide in Gaza at Columbia University in 2024.11Leila Fadel, “Mahmoud Khalil Talks with NPR after Release,” NPR, June 23, 2025.

This practice of ethnic cleansing has been replicated in the US as ICE carries out raids by masked men targeting working-class migrants, detaining them in far-flung concentration camps like “Alligator Alcatraz” in the Everglades or “Deportation Depot,” and disappearing them without trial or legal protections to El Salvador and Eswatini. Harsha Walia calls this imbrication of repression and policing “border imperialism,” a global regime where migration is criminalized for the benefit of capital, and dissent is surveilled as a strategic pillar of statecraft.

In Border and Rule, Walia writes, “Borders are not just lines on a map; they are technologies of violence.”12Harsha Walia, Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021). And those technologies are literal. For example, since 2015, ICE has contracted with commercial license plate reader (LPR) companies giving them access to billions of vehicle scans to support the ongoing raids.13Joseph Cox, “ICE Has Been Using Local Cops’ License Plate Readers in Sanctuary Cities,” Guardian, March 11, 2025.

In California, local police departments have also run unauthorized LPR queries on behalf of ICE, violating state privacy laws like California’s Senate Bill 34, which was passed in 2015 and prohibits LPR data sharing with out-of-state federal agencies. For example, CalMatters has reported that, since 2024, law enforcement agencies violated the state law more than one hundred times, especially in Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego counties.

Despite LA becoming a sanctuary city and limiting cooperation with the Feds, the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department actively collaborate with federal immigration enforcement; they have shared automated license plate readers and other surveillance data with ICE, in direct violation of SB 34.14Khari Johnson and Mohamed al Elew, “California Police Are Illegally Sharing License Plate Data with ICE and Border Patrol,” CalMatters, June 12, 2025. The California Department of Motor Vehicles has also shared Real ID and driver information with federal agencies, fueling deportation operations.15Vasudha Talla, “Documents Reveal ICE Using Driver Location Data from Local Police for Deportations,” ACLU, March 13, 2019.

This city-county-state-federal cooperation is also enforced via surveillance. For example, ICE employs Stingray devices, which are false cell‑tower simulators that vacuum up mobile phone data from entire neighborhoods.16Alexia Ramirez and Bobby Hodgson, “ICE and CBP Are Secretly Tracking US Using Stingrays,” ACLU, December 11, 2019. That data feeds directly into Palantir’s ImmigrationOS (Gotham), ICE’s predictive deportation platform. Gotham processes inputs such as workplace, nationality, and familial associations to prioritize who gets targeted next.17John Whitehead and Nisha Whitehead, “Trump’s Palantir-Powered Surveillance Is Turning America into a Digital Prison,” Counterpunch, June 4, 2025. These technologies are not neutral. Palantir cofounder Peter Thiel has long supported nationalist anti‑immigrant ideology, and Stephen Miller holds financial ties to Palantir.18Edith Olmsted, “Damning Report Exposes Stephen Miller’s Shady Ties to Palantir,” Mother Jones, June 24, 2025.

As Césaire foresaw, the fascist boomerang has returned home with its masked thugs in tow.

From Gaza to Boyle Heights, the same data-driven infrastructure is deployed to target populations for removal. As Césaire foresaw, the fascist boomerang has returned home with its masked thugs in tow. Yet, despite all its high-tech, data-driven surveillance, ICE continues to rely on police snitches and racial profiling to prey on workers early in the morning, as they leave home to work.

For example, a recent map compiled by CHIRLA reveals that a majority of ICE detentions and arrests in Los Angeles County are heavily concentrated in majority Chicano/Latino cities.19Luis Tadeo, “President Trump’s Reign of Terror in Los Angeles Focused Largely on POC, Latino Neighborhoods,” Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), July 22, 2025. Huntington Park (95 percent Chicano/Latino), Pico Rivera (90 percent Chicano/Latino), Panorama City (70 percent Chicano/Latino), and Echo Park (65 percent Chicano/Latino) are among the most affected. We can see that, despite all their technology, ICE flunkies are hard-pressed to meet their daily quotas and therefore target communities that are visibly brown.

Finally, on July 12, 2025, US District Judge Maame Ewusi‑ Mensah Frimpong issued a sweeping temporary restraining order in Perdomo v. Noem, significantly limiting ICE’s detainment authority. The order explicitly barred the use of race, ethnicity, language, occupation, or residing in particular ZIP codes as criteria for detention.20Judge Maame Ewusi‑Mensah Frimpong, Pedro Vasquez Perdomo, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Kristi Noem, et al., Defendants, US District Court, Central District of California, Case No.: 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 12, 2025, caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-dis-crt-cd-cal/117475603.html. ICE arrests in LA dropped significantly after the order was issued, proving that racial profiling was central to deportations.

The temporary restraining order was not a gift from the courts but was won through collective struggle. Mutual aid groups, community patrols, sanctuary churches, legal observers, and a host of activist initiatives have slowed or canceled ICE operations across the state. Every raid deferred, every neighborhood protected, every legal victory is a fracture in the machine.

We must use every means at our disposal to defeat this project of ethnic cleansing. At the same time, we must use this moment of crisis to propose our own internationalist, anticapitalist demands and raise the horizons of the movement for immigrant rights and sanctuary.

To Reach Aztlán, We Must Traverse Nepantla

Today’s raids take on a greater significance when we know they are orchestrated by Stephen Miller, a person who has hated Mexicans and Chicanos since his time at Santa Monica High School.21Jean Guerrero, Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda (New York: William Morrow, 2020). White supremacists like Miller hate Chicanos and organizations like the student based Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA) because our claim of belonging to Aztlán negates the completion of the settler colonial project in the southwestern territories occupied by the United States. But what is Aztlán and why does it bother white supremacists so much?

The actual, physical location of Aztlán is widely debated, and it is often considered a mythical origin story based on narratives of migration. According to the histories of the people that settled in the valley of Mexico, Aztlán—“the place of white herons”—is the land of the Aztecs (ancestors of the Mexicas) located somewhere north of the valley of Mexico.

Recent archeological research by Julio Jorge Celis Polanco claims that, thanks to the work of Paul Kirchhoff and other researchers who deciphered the codex of the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (around 1547 to 1560), it is possible to locate Azltán in the Mexican state of Guanajuato.22Julio Jorge Celis Polanco, La montaña donde nació el pueblo del sol: Las claves secretas del origen de la mexicanidad y el enigma de la montaña de las siete cuevas (Celaya, Guanajuato: Instituto Tecnológico de Celaya, 2005). And, Paul Kirchhoff, Lina Odena Güemes, and Luis Reyes García, eds., Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (Matamoros: Fondo de Cultura, 1989). The latest hypothesis isn’t widely accepted yet, and competing claims locate this mythical land somewhere in northwestern Mexico or the US Southwest.

In the late 1960s, Chicanos (working-class Mexican–Americans that reject assimilation into whiteness), relied on historical traditions and interpretations that locate Aztlán in the US Southwest. The most influential reclamation of this myth came from “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán” which was written in March 1969 on the final day of the Denver Youth Liberation Conference organized by the Chicano activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and his barrio organization Crusade for Justice. This reclamation gave Chicanos a powerful symbol of indigeneity and belonging that, for decades to come, directly challenged white supremacist, hegemonic narratives of Manifest Destiny.

The original Plan consisted of a set of strategies that could be deployed by the movement as it was emerging across the Southwest. However, according to Lee Bebout, the Plan did more than just that, as it allowed Chicanos to claim a direct lineage between themselves and the Aztecs. Thus, Chicanos were able to remap their place in the Americas by carving out a homeland beyond the boundaries of modern nation-states.23Lee Bebout, Mythohistorical Interventions: The Chicano Movement and Its Legacies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816670864.001.0001.

In the aftermath, the nationalist sections of the Chicano movement reinterpreted Aztlán in various ways. Some held it is an autonomous, sovereign territorial nation that had to be reclaimed from the lands lost after the American Invasion of Mexico (1846–1848). Other interpretations claimed Aztlán as a nation within a nation where the US had to concede self-determination for Chicanos through economic, political, and cultural community control. Finally, other cultural interpretations saw Aztlán as a spiritual homeland and “a state of mind” that safeguarded Chicano identity. Nevertheless, as the Chicano movement progressed, and its inability to confront sexism and homophobia within its ranks shone through, women, gays, and lesbians began to craft their own interpretations. For example, Cherríe Moraga saw the need for a Queer Aztlán: “A Chicano homeland that could embrace all its people, including its jotería (queers).”24Cherríe Moraga, “Queer Aztlán: the Re-formation of Chicano Tribe,” in Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland, edited by Rudolfo A. Anaya and Francisco R. Lomelí (Academia/El Norte Publications, 1989), 224–38.

Despite its mythic origin and various interpretations, Aztlán continues to be a powerful symbol in the Chicano imagination. According to Rafael Pérez-Torres, Aztlán retains its power because it functions as an “empty signifier” that can be filled with competing meanings because it has “consistently named that which refers to an absence, an unfulfilled reality in response to various forms of oppression” and because “Aztlán serves to name that space of liberation that we so fondly yearn for.”25Rafael Pérez-Torres, “Refiguring Aztlán,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 22, no. 2 (1997): 15–42, https://doi.org/10.1525/azt.1997.22.2.15.

Despite its mythic origin and its various interpretations, Aztlán continues to be a powerful symbol in the Chicano imagination.

White supremacists such as Miller hate migrants, Mexicans, and Chicanos because the myth of Aztlán associates us with Native Americans, and it legitimates our claim of belonging to this land long before the American invasion and colonization. According to Justin Akers Chacón, this type of anti-Mexican hatred is a very specific, deeply rooted phenomenon that persists, structuring race and class relations in the US up until the present.

This hatred justifies a racialized class oppression that has historically segregated and superexploited Chicanos and Mexican migrant workers. As a result, denying citizenship to Mexicans has set the standard for legal discrimination and segregation in the population after the Civil Rights movement.

Mike Davis and Justin Akers Chacón, No One Is Illegal: Fighting Racism and State Violence on the US–Mexico Border (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006).

The time has come to redeploy Aztlán as a utopia, this time grounded in new principles of Chicano Internationalism and the Land Back movement. Recognizing the power of myth, Lee Bebout argues that “myth and history form a discursive field through which power relations are constructed, contested, and refashioned.”26Bebout, Mythohistorical Interventions, 1.

Following this insight from Bebout, we must mobilize the myth and concept of Aztlán once again to contest and refashion existing power relations and to raise our horizons in the present struggle against ICE’s campaign of ethnic cleansing. When we deploy Aztlán as a utopia, as “that space of liberation that we so fondly yearn for,” as a work-in-progress, we can construct a new homeland, a sanctuary, for the international working class.

A good starting point for this equitable, socialist utopia is Cherríe Moraga’s discussion in “Queer Aztlán,” in which she argues that Chicana lesbians and gay men don’t just seek inclusion, but rather “a nation strong enough to embrace a full range of racial diversities, human sexualities, and expressions of gender.”27Moraga, “Queer Aztlán,” 235. In our search for a homeland where our love is embraced without prejudice or punishment, we must also create new ways of being in relationship to the land where citizenship and belonging are granted based on our existence on this Earth and our contributions to the places where we live through land stewardship and a socialized economy.

Just like the struggle against Proposition 187 secured (limited) access to services for migrants in education, healthcare, and other legal protections, today’s struggles against deportations and for the sanctuary city are part of the practice of Chicano internationalism and contain the seeds of a future Aztlán. This utopian vision is not about claiming the land through private property or remapping the borders through a politics of reconquest.Rather, it is informed by the politics of the Land Back movement and is about expanding the concept of citizenship and sanctuary, as a place that provides people with the resources to thrive in their autonomy.

Unlike Zionist promised lands or white supremacist melting pots built on theft, violence, and cultural exclusion, the sanctuaries that we build will be informed by a universalist internationalism that respects and celebrates cultural diversity. But like the Mexica before us, we must also embark on a journey of transformation because to reach Aztlán we must first traverse Nepantla.

In the Nahuatl language, the concept of Nepantla is derived from nepantli (middle, in-between) and it can refer to a physical place that lies in between places, as well as a conceptual state of being between two things, or liminal spaces. For Indigenous people, it was a useful concept to understand the transition between their Mexica culture and the one imposed on them by the Spanish colonizers.

Chicana scholar and theorist Gloria Anzaldúa developed the concept in her seminal work, Borderlands/La Frontera (1987), identifying Nepantla as an existential and epistemological space of being “in-between” cultures, languages, and identities.28Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987). Later on, she expanded the term, framing it as a site of conocimiento(deep awareness) and resistance, where new identities and ways of knowing emerge in this place of tension and contradiction.

Today, in this period of capitalist “polycrises,” we find ourselves in Nepantla, that place of tension and transformation in the current conjuncture that Antonio Gramsci described as an “interregnum,” where the old bourgeois order is dying and the new world is struggling to be born. We must mobilize radical, anticapitalist epistemologies and decolonial practices in our movements to raise our horizons beyond a fight for citizenship and amnesty within the empire.

In a divided, transnational class, the interests of Chicanos and Mexicanos are linked across borders, and our liberation is tied to the class struggle against capitalism.

Unless we move beyond existing demands, Latinos, Mexicans, and Chicanos will continue to be a semi-colonized population that is racially oppressed and economically hyper-exploited through a form of second-class citizenship status. According to Justin Akers Chacón, in a divided, transnational class, the interests of Chicanos and Mexicanos are linked across borders, and our liberation is tied to the class struggle against capitalism and not to “national liberation” within traditional liberal-bourgeois frameworks.29Justin Akers Chacón, The Border Crossed Us: The Case for Opening the US–Mexico Border (Chicago: Haymarket Books, August 2021).

Conclusion

As I travel throughout California, I often wonder how this place might have been hundreds of years ago, before colonization and capitalism transformed its landscapes through land theft, cattle ranching, invasive species, canalization, and industrialized agriculture. Although it may sound farfetched, if you look closely, during a rainy season it’s possible to see Aztlán emerge within our midst, somewhere in California’s Great Central Valley between Fresno and Bakersfield.

For millennia, Tulare Lake—called Paʼashi (“big water”) by the southern Yokut—was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, fed by the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern Rivers. In 2023, exceptional rain, snowmelt and atmospheric rivers resurrected over one hundred thousand acres of the lakeshore, momentarily drowning farmland and restoring marshes dense with tules, willows, buttonbush, and vibrant bird habitats.

The return of the lake drew massive waterfowl flocks—sandhill cranes, geese, pelicans, herons, white egrets, bitterns—and native turtles and frogs in a vivid but fleeting revival.30James Von Tersch, “The Resurgence of Tulare Lake in California,” Sierra Nevada Alliance, August 8, 2023. This rebirth briefly illuminated ancestral landscapes lost to agriculture and irrigation works. Such episodes demonstrate the memory of water, and they highlight the huge potential for Land Back, degrowth, and rewilding initiatives.

This is why studying, reclaiming, and redeploying myths like Aztlán and the concept of Nepantla is so important. These categories, which are approximations of reality, allow us to articulate a politics of Chicano internationalism that can be realized in the decolonized lands of Aztlán, Turtle Island, and Abya Yala. We must envision new utopias imbued with our origin stories of possibility.

For example, recently a group of Indigenous teens kayaked the length of the Klamath River, less than a year after the water dam was removed. Closer to home, in the unceded ancestral homelands of the Tongva–Gabrielino people, youth from LA County’s autonomous Indigenous school, the Academia Anawakalmekak, are growing the next generation of environmental stewards in partnership with the Gabrielino Shoshone Nation and the Chief Ya’anna Learning Village.

These initiatives are glimpses of what can be, of the new lives and futures we must begin to rehearse today. These initiatives can inspire new homelands where citizenship and belonging are granted based on our contributions to our communities and stewardship of the land. This path begins by understanding that the seeds of Aztlán are contained within the struggle against ICE and the sanctuary movement of today, as imperfect as it is. But to get there, we must first traverse Nepantla. ×

Rian Dundon is a documentary photographer from Portland, Oregon. His photo essay was supported by Magnum Foundation and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, with funding made possible by the Puffin Foundation.

Notes & References

- Matthew Rozsa, “Trump Has Deployed More Troops in LA Than Syria and Iraq,” Truthout, June 2025.

- Ginger Adams Otis and Robert Barba, “The White House Marching Orders That Sparked the LA Migrant Crackdown,” Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2025.

- Maga Miranda, “Defend the LAnd,” Spectre (online), June 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.63478/1UZ20PI3.

- “Ours Is a National Liberation Movement Rooted in Class Struggle—We Are Raza Internationalists,” Unión del Barrio, August 14, 2025, tinyurl.com/5bzxhnte.

- Glenn Sacks, “Anti-Union Group Deploys False Allegations of ‘Antisemitism’ to Attack UTLA,” Los Angeles Daily News, August 13, 2025.

- Josh Hawley, “GOP Senator Accuses LA Immigrant Rights Group of Aiding ‘Unlawful’ Acts During Ongoing ICE Protests,” LAist, June 11, 2025.

- Kelly Rissman, “Inside the ICE Offices Where Morale Is ‘Miserable’ and the Pressure Is High,” Independent, July 11, 2025.

- “Stephen Miller,” Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d., tinyurl.com/3wuudd79.

- Jason Wilson, “Leaked Emails Reveal Trump Aide Stephen Miller’s White Nationalist Views,” Guardian, November 14, 2019.

- “Stephen Miller.”

- Noura Erakat, “The Boomerang Comes Back,” Boston Review, February 5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.63478/GU3ZD2QU.

- Leila Fadel, “Mahmoud Khalil Talks with NPR after Release,” NPR, June 23, 2025.

- Harsha Walia, Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021).

- Joseph Cox, “ICE Has Been Using Local Cops’ License Plate Readers in Sanctuary Cities,” Guardian, March 11, 2025.

- Khari Johnson and Mohamed al Elew, “California Police Are Illegally Sharing License Plate Data with ICE and Border Patrol,” CalMatters, June 12, 2025.

- Vasudha Talla, “Documents Reveal ICE Using Driver Location Data from Local Police for Deportations,” ACLU, March 13, 2019.

- Alexia Ramirez and Bobby Hodgson, “ICE and CBP Are Secretly Tracking US Using Stingrays,” ACLU, December 11, 2019.

- John Whitehead and Nisha Whitehead, “Trump’s Palantir-Powered Surveillance Is Turning America into a Digital Prison,” Counterpunch, June 4, 2025.

- Edith Olmsted, “Damning Report Exposes Stephen Miller’s Shady Ties to Palantir,” Mother Jones, June 24, 2025.

- Luis Tadeo, “President Trump’s Reign of Terror in Los Angeles Focused Largely on POC, Latino Neighborhoods,” Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), July 22, 2025.

- Judge Maame Ewusi‑Mensah Frimpong, Pedro Vasquez Perdomo, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Kristi Noem, et al., Defendants, US District Court, Central District of California, Case No.: 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 12, 2025, caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-dis-crt-cd-cal/117475603.html.

- Jean Guerrero, Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda (New York: William Morrow, 2020).

- Julio Jorge Celis Polanco, La montaña donde nació el pueblo del sol: Las claves secretas del origen de la mexicanidad y el enigma de la montaña de las siete cuevas (Celaya, Guanajuato: Instituto Tecnológico de Celaya, 2005). And, Paul Kirchhoff, Lina Odena Güemes, and Luis Reyes García, eds., Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (Matamoros: Fondo de Cultura, 1989).

- Lee Bebout, Mythohistorical Interventions: The Chicano Movement and Its Legacies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816670864.001.0001.

- Cherríe Moraga, “Queer Aztlán: the Re-formation of Chicano Tribe,” in Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland, edited by Rudolfo A. Anaya and Francisco R. Lomelí (Academia/El Norte Publications, 1989), 224–38.

- Rafael Pérez-Torres, “Refiguring Aztlán,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 22, no. 2 (1997): 15–42, https://doi.org/10.1525/azt.1997.22.2.15.

- Mike Davis and Justin Akers Chacón, No One Is Illegal: Fighting Racism and State Violence on the US–Mexico Border (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006).

- Bebout, Mythohistorical Interventions, 1.

- Moraga, “Queer Aztlán,” 235.

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987).

- Justin Akers Chacón, The Border Crossed Us: The Case for Opening the US–Mexico Border (Chicago: Haymarket Books, August 2021).

- James Von Tersch, “The Resurgence of Tulare Lake in California,” Sierra Nevada Alliance, August 8, 2023.