Here, William Clare Roberts enters an ongoing debate in the pages of Spectre, regarding the role of philosophy and metaphysics as a ground and resource for Marxist strategy. For earlier entries in this debate, please see the following articles:

- Aaron Jaffe, “Marxism, Spinoza, and the ‘Radical’ Enlightenment”

- Landon Frim and Harrison Fluss, “Reason is Red”

- Neil Braganza, “Philosophy as Life-Making Struggle”

- Darren Roso, “Materialism and the Crisis of Marxism”

I. “Strugglism” and political justification

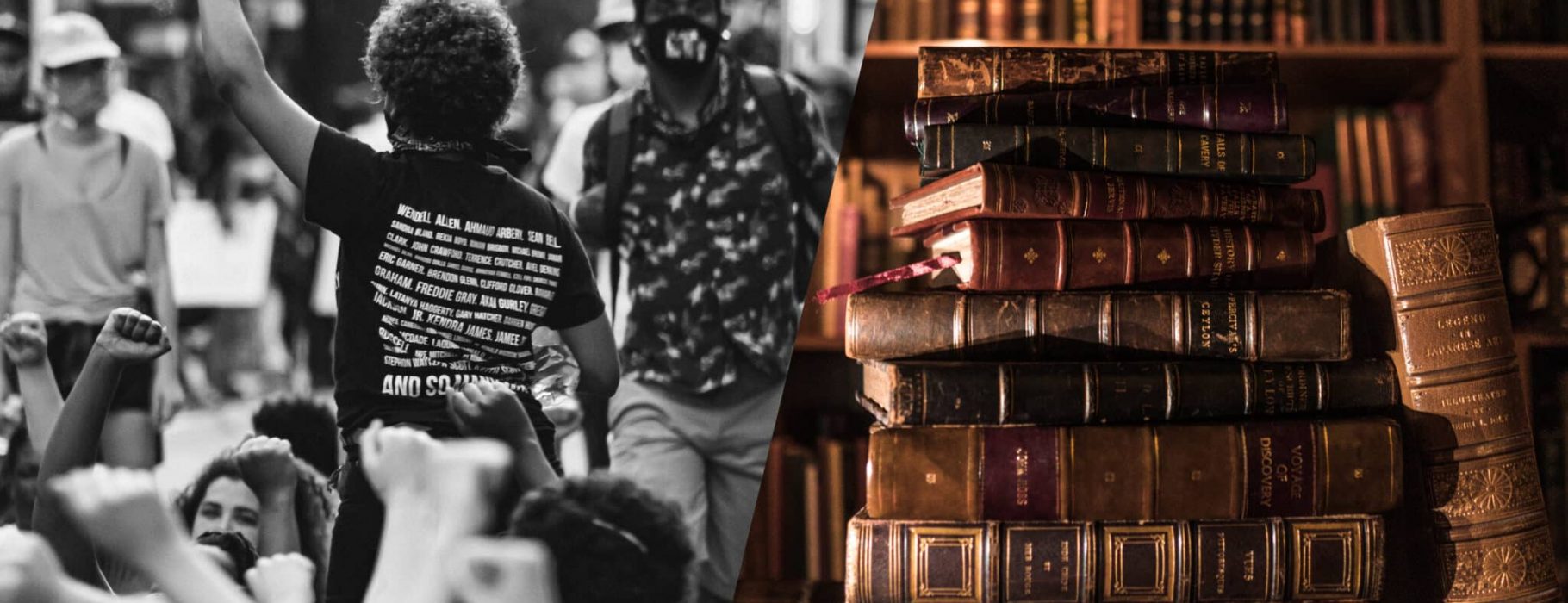

Left-wing writing about politics seems always to begin in one of two ways: with the depredations of the powerful or an invocation of popular mobilization against them. Radical politics is the politics of self-emancipation. It seems natural, therefore, that writing about and in the service of radical politics should locate the beginning of that politics in the collective resistance of protesters, strikers, rioters, and revolutionaries. Whether it is “young, angry protesters in Shanghai,”1https://spectrejournal.com/uprising-against-lockdowns-and-precarity-in-china/ “a militant ten-week strike against one of the most union-busting higher-education institutions in the United States,”2https://spectrejournal.com/a-tale-of-two-strikes/ or “nationwide strikes on the railways at British Telecom (BT) and by postal workers at Royal Mail,”3https://spectrejournal.com/tories-collapse-amidst-a-growing-strike-wave/ recent writing in these pages has adhered to this tradition. Radical thinking, writing, and theorizing takes its impetus and direction from popular agitation, protest, and resistance.

This is reasonable and good, but it also courts certain risks. These risks have been highlighted by the debate between Aaron Jaffe and the team of Landon Frim and Harrison Fluss. According to Jaffe, intellectuals on the Left ought to be a bit skeptical of the power of ideas, modest in their claims to perceive “first principles” for emancipatory struggles, and oriented by the effort “to better track, galvanize, and respond to actual social needs,” as these needs show themselves in popular struggles. This perspective tends to reinforce the norm just mentioned, to justify starting where the activism is.

Frim and Fluss are unmoved by Jaffe’s argument. They object to what they call his “ideology of ‘strugglism’” because it seems to them to ignore or disclaim the need to choose among struggles and to justify our choices. “Something as important as intervening in the world, and affecting people’s lives,” they write, “requires sound justification.”

If we are committed to ‘the idea’ of communism, then we are also committed to its practical realization and all the real world consequences that this entails. Being serious about ideas means confronting their flesh-and-blood impacts when they come to fruition. Intellectual maturity, then, demands an accounting of our political ideals. We have to care that we are right and our enemies are wrong. And this means something more than being on the ‘right side’ of a particular issue; it means knowing that your politics are grounded in an accurate conception of reality and of what is objectively good for human beings. Otherwise, every political thought-piece we pen, every protest we support, every party meeting we attend, is just an example of playing with other people’s lives and futures.

I am torn. I find very little to disagree with in Jaffe’s argument, but Frim and Fluss have a point in their advocacy of intellectual responsibility, of being accountable for the ideas we uphold and promote. On the other side, however, I don’t think they follow through on their own demand for such an accounting.

Frim and Fluss are right that there is a tendency on the Left to outsource responsibility to the streets. When we, as Leftist intellectuals, take our impetus and direction only from the streets, we are also outsourcing our judgment to the streets. We disavow, thereby, our own activity, the decisions we make, and the criteria by which we make them. Frim and Fluss are right, I think, that we need to be accountable for the struggles we support, not only accountable to those struggles.

Given this basic agreement with Frim and Fluss, I was disappointed, however, that they eschewed anything like “an accounting of our political ideals.” I searched their essay in vain for “a clear idea of why we fight, and how best to achieve our goals.” The questions with which they open—“What kind of struggle is worth our effort? What goals should we aim for? Whom should we build solidarity with, and why?”—not only remain unanswered, they go completely unaddressed. Instead of “politics and political philosophy,” the reader gets a disquisition on the need to affirm that “the entire universe is an intelligible Whole,” that “everything within nature is interconnected and governed by natural laws,” and that “historical categories are really parasitic upon a more basic—often unspoken—architecture of the world.” What is going on here?

Frim and Fluss make two basic errors. First, they think that socialist politics must be grounded in universal moral propositions. Second, they think that these universal moral propositions must themselves be grounded in a naturalistic ontology. Neither of these claims is true. Indeed, given their understanding of the grounding relation, neither of these claims even makes sense. In order to see why, it is necessary first to clear away some preliminary matters that distract from the main arguments advanced by Frim and Fluss. I will then turn to the two fundamental propositions advanced by their essay, indicating why each, in turn, fails. I’ll conclude with some more general considerations for how I think socialists ought to think about the relationship between their basic principles and their political interventions.

When we, as Leftist intellectuals, take our impetus and direction only from the streets, we are also outsourcing our judgment to the streets. We disavow, thereby, our own activity, the decisions we make, and the criteria by which we make them.

II. The monism of Frim and Fluss

Frim and Fluss seem to think that a clear and consistent political line will emerge by deduction from a Hegelian-Spinozist account of fundamental ontology. They claim that “taking theory seriously is really the most practical course of action,” precisely because, from a rational insight into “the nature of reality,” dialectical monism both “demonstrates the unity of human nature and the human good” and “establishes the real basis for international solidarity.” If we get clear on the rational architecture of the entire universe, we can then reason our way to “a clear idea of why we fight, and how best to achieve our goals.”

I’m skeptical, if only because the champions of this deductive rational procedure do not themselves deduce any conclusions from their stated premises. Their essay does not follow chains of reasoning so much as it allows enthusiasm to tangle them, break them, and melt them down into a confused lump. If caring about being right and being rational mean anything, they must mean thinking clearly and following the argument where it goes, which Frim and Fluss do not do.

Right off the bat, Frim and Fluss cannot decide whether the monism they favor is “require[d]” for Marxism, or whether it merely “supports” it. These are very different claims. If Marxism requires monism, then only monism can support Marxism. However, Frim and Fluss say nothing to substantiate this requirement claim. The only argumentative strategy that would suffice is one of showing the incompatibility between Marxism and anything other than monism. That strategy would require defining Marxism—identifying that set of propositions the affirmation of which is necessary and sufficient for being a Marxist—and showing that anything other than monism would imply the negation of one or more of its core propositions. I, for one, would be interested to see them attempt this. It is clearly not a strategy they pursue in their essay, however.

Instead, Frim and Fluss fall back on the weaker thesis that monism supports Marxism. Even here, though, they struggle to supply any good reason to believe their thesis. They claim, near the end of their essay, to have provided seven arguments for the conclusion that monism supports Marxism.4They say these are arguments for the conclusion that “monism is necessary for a socialist politics,” but this is neither a true description of the arguments nor a plausible claim. There have been many committed practitioners of socialist politics who were and are not monists in Frim and Fluss’ sense. Instead, it is clearly a normative claim: Frim and Fluss think that monism should be necessary for socialist politics—i.e., that socialists should be monists. All of the claims about the indispensability of dialectical monism are simply recommendations that socialists would be better off if they were monists, recommendations that have been dressed up in military dress uniforms so as to seem more imposing.

Frim and Fluss cannot content themselves with making merely pragmatic recommendations, since that would require them to indicate some plausible and concrete benefits that socialists should expect from converting to dialectical monism. The first four amount to variations on the claim that monism renders the world intelligible and events of the world explicable, since it excludes immaterial or supernatural causal principles (including free will). The fifth, sixth, and seventh turn to practical matters. Monism (5) “provides the basis for universal solidarity as a logical consequence of our shared human nature.” It also (6) furnishes the only non-question-begging foundation for ethics, since it grounds ethics in naturalism rather than decisionism. Finally, (7) it secures our hopes for improving the world through intentional action.

The first four arguments, as well as the seventh, are not specific to the dialectical monism in which Frim and Fluss wish to ground socialism. Rather, (1) naturalism, (2) the rational intelligibility of all processes, (3) the causal explicability of all events, and (7) the hope of improving the world through intentional action, are all broadly affirmed by materialists of all stripes. Not only do you not need dialectical monism in order to conclude that there are no immaterial sources of information in the universe, but you can be a fully-paid-up, card-carrying member of the eliminative materialism club and also be a liberal capitalist—or a brownshirt, for that matter. These five claims are not wholly indeterminate—many people really do believe in an interventionist god, miracles, spirits, and the radical freedom of the will—but the secular, rationalist, natural scientific practices these five claims endorse do not have to take the theoretical form of dialectical monism, nor do they have to issue in Marxist politics.

The actual transmission belts of Frim’s and Fluss’s argument are supposed to be the fifth and sixth claims. This is why they spend so much of their essay arguing that monism is the basis for solidarity and the basis for action. Unfortunately, words spent is not a measure of progress made.

If caring about being right and being rational mean anything, they must mean thinking clearly and following the argument where it goes, which Frim and Fluss do not do.

III. The limits of solidarity

There are two fundamental problems with Frim’s and Fluss’s arguments in these sections of the essay. First, even if they were right that “universal solidarity, the unity of all peoples, regardless of particular cultures or geographies” is grounded in the metaphysical unity of all existence and that “the more rational we are, the more we clearly perceive our identity with others,” there is no path from this universal, rational solidarity to socialist politics.

Remember that one of Frim’s and Fluss’s opening questions was, “Whom should we build solidarity with, and why?” The answer to that question cannot be, “everyone, because ‘the monist understands that their neighbor literally is, in some substantial sense, themselves.’” I may have a substantial unity with everyone—and everything!—else, but I am not just substance. I am also a finite being whose continued existence and thriving may be threatened by my neighbor’s continued existence and thriving. Politics—including socialist politics—is a matter of confronting and negotiating conflict through struggle. Universal solidarity and substantial identity are radically inadequate to those tasks. The struggles in which we are engaged are not between universal solidarity, on the one hand, and universal enmity, on the other.

Frim and Fluss know this. They are clear-eyed in stating that “monism as such cannot identify [the] divisions within humanity” that are relevant for political action in any circumstance. They know that “there is no cosmic battle between good and evil,” but only a series of struggles among human beings. But they do not take seriously enough the consequences of their own knowledge. They claim:

We should care about the exploited worker, as well as oppressed races, genders, and ethnicities, not because there is something sui generis about their particular identities, but because they are all human beings. And conversely, we militantly oppose the capitalist, the racist, and the transphobe, not because they incarnate some alien, radical evil, but because they cause human suffering.

This won’t do at all. Exploited workers, as well as oppressed races, genders, and ethnicities, cause human suffering, too. And the capitalist, the racist, and the transphobe are all human beings. Our solidarity with you should not be contingent on you not causing human suffering. Nor should it be triggered by the fact that you are a human being. The former is far too exacting; the latter is far too lax. If our militant opposition were triggered by something so abstract and ubiquitous as “causing human suffering,” the only result would be misanthropy.

Political solidarity is owed to the unfree, but we also have to recognize that efforts to overcome unfreedom—projects of emancipation, even ones with a universal horizon—will necessarily cause suffering and create new forms of unfreedom. Committing one’s solidarity will always involve making judgments about whether the suffering and unfreedom caused by the emancipatory movement negates the suffering and unfreedom alleviated by it. These judgments involve, necessarily, counterfactuals and weighing incommensurables. Militant opposition to all those who cause human suffering has nothing to contribute to this difficult labor. Neither does universal solidarity. Hence, Frim and Fluss have given us a universal moral proposition that is inherently incapable of helping us choose among struggles or justify the choice we have made.

Exploited workers, as well as oppressed races, genders, and ethnicities, cause human suffering, too. If our militant opposition were triggered by something so abstract and ubiquitous as “causing human suffering,” the only result would be misanthropy.

IV. Transhistorical, metaphysical truths cannot guide action

The second, even more serious problem is that dialectical monism cannot serve as the basis for any politics whatsoever, for the very simple reason that metaphysical and necessary truths cannot tell us anything about how to act or which states of affairs to prefer. This has nothing to do with any appeal to free will. Nor does it rest on an empiricist division between what is and what ought to be. Rather, it is simply a matter of time.

If dialectical monism is true, then it is always true. Certainly, its truth is not affected by historical events on this third planet swinging around a minor star on the edge of one galaxy. But universal solidarity is “a logical consequence of our shared human nature,” a simple logical deduction from our universal interconnection. “Caring about others is,” as Frim and Fluss put it, “not a choice, but a necessity.”

Hence, universal solidarity is a necessary effect of our shared humanity, even in the midst of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, even in the killing fields and the death camps of the Eastern Front. Caring about one another is a necessity, even as I stick a knife in your back. I understand that my neighbor is, in a substantial sense, myself, even as I turn them in to the secret police. I am supplied with the universal motivation for stamping out suffering, even as I release the bomb that will obliterate an entire city.

I cannot negate transhistorical, metaphysical truths by my actions. Nor, therefore, can I realize them. They are always realized, or else they would not be “universal constants.” And that means that transhistorical, metaphysical truths cannot tell us what to do. They cannot guide our action. They are constants. No matter what the outcome of the current conflicts, universal solidarity and substantial identity will persist, unaffected. They will be there, in their full normatively-charged, universally-descriptive glory, no matter what we do.5Trying to wriggle out of this conclusion is a favorite pastime of many on the Left. Frim and Fluss are worried about a “hyper-historicism” in which all continuity, and with it all change, is “lost in the buzzing, blooming confusion.” They fail to appreciate that this cannot be remedied by the addition of “unchanging universal laws.” They claim that “metaphysical laws,” precisely because they do “not undergo change … can register change, and allow us to make sense of rapidly evolving conditions over time.” There may be some truth to that, but not the sort that can help them, or us, choose among struggles or justify our choices.

Frim and Fluss tell us to put our faith in the “innate, rational tendency of human beings to maintain and increase their power by combining with others.” As a metaphysical law, this innate, rational tendency is present even when the others in question are one’s fellow Nazis and the power obtained by combining with them is the power to exterminate those who threaten one’s sense of self. “Rationalism,” Frim and Fluss assure us, “only asserts that all events, whether natural or man-made, whether good or bad, can in principle be understood.”6I must register my belief that Frim and Fluss are not entitled to insert “tendency” in this claim; it is a slippery word, like “in principle,” which only allows them to avoid noticing the consequences of their claims.

The obnoxious thing about action is that it takes place in the present, on the edge of the not-yet. We don’t know how it’s going to turn out. Yes, I suppose we can take some comfort in the fact that, no matter what, “all events, whether natural or man-made, whether good or bad, can in principle be understood.” Not much comfort, though, since the events that turn out to be understandable in principle, and fully intelligible, may also be the events that turn out to kill us and everyone we love.7The comfort that our existence was necessary and intelligible, and that the fact of our existence can never be eliminated—we are all eternal ideas in the mind of god—is as cold a comfort as the Epicurean assurance that we did not exist for an eternity before we were born and will not exist for an eternity after we die.

Dialectical monism cannot serve as the basis for any politics whatsoever, for the very simple reason that metaphysical and necessary truths cannot tell us anything about how to act or which states of affairs to prefer.

V. The burdens of judgment remain

Nothing I have argued here hinges on dialectical monism being incorrect. The truth of dialectical monism is neither here nor there. I am happy to grant the truth of dialectical monism. Unlike Frim and Fluss, however, I don’t think converting people to the good news of dialectical monism will do any political good. Nor do I think any one particular politics is downstream from dialectical monism. Even if belonging to a certain political party or party fraction were derivable from dialectical monism, that party or faction would still confront the burdens of judgment in every conjuncture. It would have to think through the new situation from the ground up, deciding what to do without being able to rely on dialectical monism.

Frim and Fluss dismiss the burdens of judgment because the phrase was coined by John Rawls and Rawls was a liberal. But even liberals speak the truth sometimes. They are, after all, rational and self-interested beings who seek to increase their power by combining with others. In an intelligible world governed by natural laws, tracking and expressing the truth is often a good way of combining with others. The burdens of judgment are not about enforced philosophical humility, building policy consensus, or methodological pluralism. Rawls’s point was that agreement on basic principles is not enough to secure a common mind about what to do.

This is true for a number of reasons, which will be in play to differing degrees in any given conjuncture. Empirical evidence is complex and often open to conflicting interpretations. People can reasonably disagree about how much weight to give to various matters under consideration. The concepts we use are necessarily vague or indeterminate in certain instances. Our interpretation and assessment of both the evidence and the normative concepts involved in a decision are inescapably shaped by our personal experiences. In a complex world, there will always be hard trade-offs between valid concerns on different sides of a question; there are no cost-free courses of political action. Finally, no social institution can incorporate and honor every value we have.

There is nothing specifically liberal about Rawls’s point. Radicals, communists, etc., can agree on basic principles while disagreeing vociferously about everything else. Even a cursory glance at the history of any revolution or emancipatory movement is sufficient to demonstrate this. Rawls’s point is also entirely compatible with dialectical monism. The burdens of judgment confront any self-interested and rational finite intellect acting in an intelligible world in which events are causally connected and systematically or structurally interrelated. Indeed, to deny the burdens of judgment is to forget that we are each—separately and together—finite intellects, and that human power is very limited and infinitely surpassed by the power of external causes.

This, finally, brings me back to the core of my agreement and my disagreement with Frim and Fluss. They are absolutely right to say that “something as important as intervening in the world, and affecting people’s live, requires sound justification.” But, for finite intellects, this justification can never take the form of knowing that we are right and our enemies are wrong. Intellectual maturity—being serious about ideas—means taking up the task of justification anew in every circumstance, knowing that, precisely because politics needs an accurate conception of reality, it can never rest in the certainty of having secured it.