A stirring history of the mass struggle from below that won legalized, state-funded abortion in Argentina.

“The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? Is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today?…If so, then there is a secret protocol between the generations of the past and that of our own.”1Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm.

The indelible abortion story of my life is my auntie Vicki’s. It was the first I ever heard. She found herself in her 20s with an ectopic pregnancy (when the fertilized egg implants and begins to grow outside of the uterus—in her case, in a fallopian tube). Ectopic pregnancies are both non-viable for the fetus and life-threatening for the gestator. She did what she had to: she got an illegal abortion. After all, she had a life of her own, she had dreams, hopes.

I remember her telling me that she was in some room God knows where and there were complications. She thought she was going to die, or maybe that she was already dead. She told me she saw a light that neared and neared and neared, and she kept thinking, my parents don’t know where I am. Somehow, she survived.

Fifteen years later, my mom told me that she had had three illegal abortions, the last with my father a few months after they’d gotten married (“I didn’t even know him!”…We laughed). Her sister, my aunt, had had around seven illegal abortions, and another auntie close to twenty. “I think by those last ones, she was looking to die,” my mom added after a pause.

I have thought a lot about how even my mother, left-leaning and staunchly pro-abortion, waited so long to tell me, though I had been a vocal feminist for most of my teen and adult life and had been doing abortion work for more than four years. In “Twice Is a Spanking,” Jennifer Baumgardner writes about a similar experience with her friend Marion, “the kind of feminist who wears an I Had An Abortion T-shirt with Talk To Me scrawled by hand beneath the message.” And yet, “dauntless radical” though she was, Marion rarely spoke of her second abortion.

“One abortion—that happens. Two? Well, to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, two smacks of carelessness. My father, a doctor in Fargo, North Dakota, expressed surprise when I mentioned the second-abortion stigma to him: ‘It’s odd, given that it’s the exact same situation as before, no more or less of a life.’”2Jennifer Baumgardner, “Twice Is a Spanking,” in Abortion Under Attack, ed. Krista Jacob (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2006). Thank you to Michael Dola for pointing me to this essay.

over yerba mate, on the balcony, years and miles apart, weave together lessons and lineages of oppression and rebellion, passed down through generations.

I thanked my mother for telling me, tried to assuage her concern that I might take it personally, and told her I was proud of her.

These confessions and asides, moments of complicated hesitation and relinquishment and humor, over yerba mate, on the balcony, years and miles apart, weave together lessons and lineages of oppression and rebellion, passed down through generations. An oral tradition of sorts; the significance of histories that were criminalized and took place largely underground. It is the stuff feminist movements are made of, all that we carry in the home and to the streets.

That conversation with my mother happened a few months after abortion was legalized in our home country of Argentina. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense. The dam broke, in more ways than we could have imagined.

On the night of December 30, 2020, I tried to stay up, cycling through dozing off and waking with a start, phone in hand. I was monitoring the livestreams of Buenos Aires’s streets and central plaza, where millions were gathered, awaiting the long-anticipated verdict on the bill that would legalize abortion. Green pañuelos, or handkerchiefs, symbols of the campaign for legal, safe, and free abortion, colored Buenos Aires and every other city—visual markers of time and energy.

For hours, activists chanted, drummed, danced, painted, gossiped, squeezed each other’s hands, distributed food and water. There were hushes and lulls and bursts as the longest congressional debate in Argentinian history raged inside the National Congress building, and information circulated among the aborterxs outside. A little past 3:00 a.m., New York time, in my tiny apartment, I watched through a screen as the announcement came over the loudspeakers in the plaza: abortion was now legal in Argentina as part of its socialized healthcare system, the largest Latin American country to pass such a law. The crowd erupted in embraces, tears, jumps of joy, es ley mi amor, es ley.3It’s law, my love, it’s law. Author’s translation.

I yelped and cried and WhatsApp’d my mom, my aunt Vicki, their friends. I thought about the push and pull of time and history, the women who raised me and taught me, my own abortion activism, and all the running, entangled threads of life and resistance.

“We are the end, the continuation, and the beginning. We are the mirror that is a crystal that is a mirror that is a crystal. We are rebelliousness. We are the stubborn history that repeats itself in order to no longer repeat itself, the looking back to be able to walk forward.”

4Subcomandante Marcos, “Today, Eighty-five Years Later, History Repeats Itself” (speech, inaugural ceremony of the American Planning of the Intercontinental Meeting for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism, April 6, 1996), https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/subcomandante-marcos-our-word-is-our-weapon#toc40.

It was a moment decades in the making. A reminder that history belongs to us.

The next morning, the New York Times published an article by Daniel Politi and Ernesto Londoño reporting on the news, titled “Argentina Legalizes Abortion, a Milestone in a Conservative Region.” Though the title’s second clause implies a backward Latin America, Argentina’s legalization of abortion in fact already vastly surpasses the level of abortion rights granted by the United States since Roe v. Wade. Abortion and contraception in Argentina are now not only legal, but free to all without exception as part of its healthcare system—rights far removed from US reality. The United States is the one who must now catch up.5Daniel Politi and Ernesto Londoño, “Argentina Legalizes Abortion, a Milestone in a Conservative Region,” New York Times, December 30, 2020.

To take the point of comparison further, Argentina’s socialized healthcare system played an important role in facilitating the abortion movement’s growth and the victory of legalization. It is one thing to argue that abortion is healthcare in a society that already believes free and accessible healthcare to be a right; it is quite another to have to call for both (let us consider, for example, the differences of reception to the popular slogan “Free Abortion on Demand”). Not only that, but the integration of abortion services into all other types of medical care in many ways helps preempt the particular vulnerabilities of freestanding abortion clinics, a crucial legacy of abortion in the United States entwined with the persistence of the Hyde Amendment, which bans the use of federal funds such as Medicaid for abortion services.

The siloing of abortion from hospitals and other medical practices through the establishment of clinics in the United States has had a major downside that is key to the anti-abortion movement: “a nationwide network of targets—and isolating abortion from the rest of mainstream medicine.”6Nora Caplan-Bricker, “Why Are Abortions Performed in Clinics?” Slate, November 16, 2015. This separation and privatization of abortion in the United States has contributed to the domination of nonprofits on the question, especially around political strategy, which helped defang the once-militant and radical abortion movement, channeling its energies into centrist, compromising lobbying. The main player in this transformation has, of course, been Planned Parenthood, an organization which discourages clinic escorts and pro-abortion activists from countering antis in front of clinics and elsewhere.

Though momentous, the bill passed in Argentina (the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy Bill) was not the same legislation developed by the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion—the organizational and driving force of the abortion movement. The bill put forward by the movement in the streets was drafted collectively by its more than five hundred different constituent organizations and unions. What passed in Congress was, instead, a watered-down version of what the campaign presented, a result of the contestation between Argentina’s clerical lobby and the abortion movement.

We are the stubborn history…

Important concessions enshrined in the bill include the legalization of abortion up to fourteen weeks of pregnancy except for cases of rape or incest, a ten-day window in which one must receive a requested abortion, and the allowance for conscientious objection from medical professionals who refuse to perform abortions.7There has been much debate within the campaign around codifying a time frame in which an abortion must be received. Though similar to a traditional abortion waiting period in other countries, activists in the campaign saw the inclusion of a time window as necessary to ensure that requested abortions were performed in a timely manner. The campaign’s original proposal was for a five-day window. The anti-abortion right, however, was able to successfully extend the proposed time frame, with the idea that more time means higher chances of dissuading people from ultimately getting their abortions. In contrast, the campaign demanded the decriminalization of abortion, full stop. No term limits, no stipulations, but the core idea that free, safe, legal, and unrestricted abortion is a fundamental democratic right, just like any other form of healthcare, which should be guaranteed to all.

I point to this not to diminish the victory but to draw out the dynamics: a mass radicalization around abortion, especially among young people; the national campaign that has achieved its main target of legalization after more than fifteen years of organizing; a Catholic Church structurally tied to the state coupled with a mobilized, reinvigorated religious (not just Catholic) right; and a new center-left government that is divided on the question, with key sections embedded inside the abortion movement. It is a new moment.

My grandfather, Ernesto “Tito” Valle, was a man of few words, though he had a striking, bellowing voice. He sold cold cuts at the peak of industrial refrigeration in Argentina, before the opening up of the economy, and the great influx of imports drove his livelihood into the ground. He kept his money under his mattress until the day he died.

The Argentinian economic crisis was long in the making. The US-backed military dictatorship of the second half of the twentieth century opened the door to neoliberal policies, undermining the import substitution programs that had supported the country’s industrial base in the 1960s, and skyrocketing external debt was absorbed into public debt, placing the burden on the poor and working class. Argentina became anchored to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), deepening relationships among multinationals, financial capital, and local business elites.

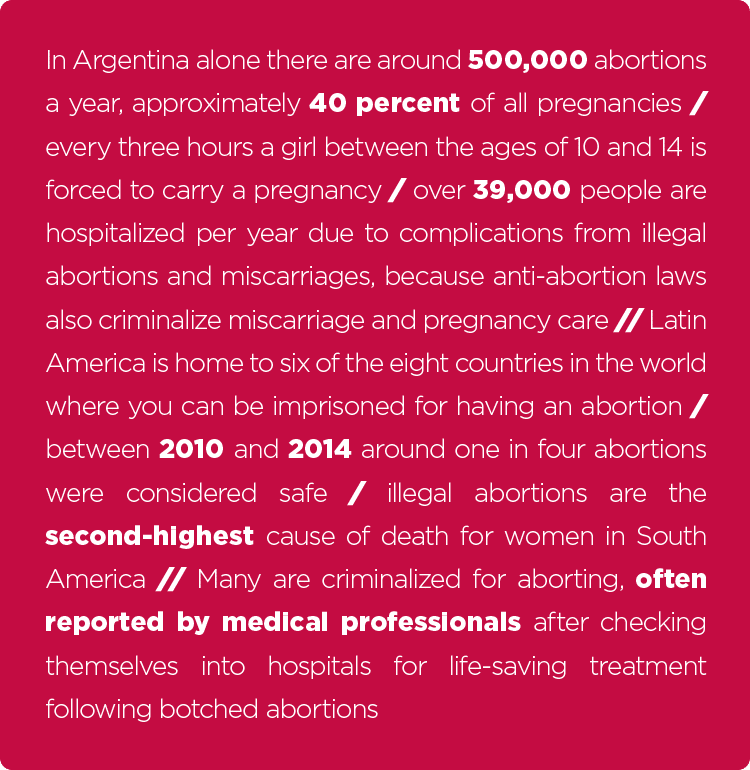

A dizzying stream of data

preachers of life dole out sentences of death

Even after the fall of the dictatorship, the debt burden and inflation plagued the country. In the early 1990s, the government pegged the peso to the dollar on a one-to-one basis, an equivalence that did not last long. The private sector continued to borrow money, for which the government took responsibility, and the process of privatization was accelerated while public investments and funding for social services was drastically cut. In short, the economy kept spiraling, and the poor kept paying.

While the 1990s saw a sharpening of neoliberalism, it was also a period of rich domestic, regional, and international fights against austerity. The annual National Women’s Gatherings—home base of the feminist movement in Argentina and the broader region—were expanding to all Argentinian provinces beyond Buenos Aires, to areas not as urban, not as white, and so on. In 1992, Pride marches were inaugurated, and feminists began to participate in them, bringing together different sectors, such as unions and human rights organizations, and transforming the events themselves into sites of organizing and coalition building for and with groups that had until then remained relatively marginalized. This came to the fore during the struggle against former President Carlos Menem’s proposed reform to the Constitution, including an anti-abortion clause codifying that life starts at conception. A mass movement came together against the proposed constitutional reform and won.

By the end of 2001, Argentina was $142 billion in debt and the public’s supposed dollar bank accounts were frozen, restricting people’s ability to withdraw cash. In direct response, uprisings broke out on December 19 and 20, 2001, particularly in large cities such as Buenos Aires and its greater region, La Plata, Rosario, and Córdoba. Millions took to the streets, the majority unaffiliated with any political party or organization. From December 19, 2001, to January 2, 2002, in what has been dubbed the “thirteen days that shook Argentina,” mobilizations spread and gained militancy while five different presidents came and went: Fernando de la Rúa declared a state of emergency and resigned on December 20, Ramón Puerta lasted two days after that, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá eight, Eduardo Camaño made it from December 30 to January 2, and Eduardo Duhalde took office on January 2, remaining in power until May 2003.

The emperor was beyond naked. A profound political, social, and cultural shift was unfolding.

Thirty-nine people, nine under the age of 18, were killed by police and security forces. The chant that defined the moment distilled it all: “Que se vayan todos!” (“Everyone Must Go!”—by “everyone,” of course, people meant the politicians). Neighborhood councils, organizations of the unemployed, and takeovers of factories by workers were all part of this conjuncture of transformation. The emperor was beyond naked. A profound political, social, and cultural shift was unfolding.

Various modalities of struggle, learned and formed in different historical moments, converged in this period against common enemies—traditional political parties, finance capital, the state itself. Women and the feminist movement were among the first protagonists of this process that had opened up. In this context, the question of abortion became a salient component of the explosion of popular social movements across the country, and the uprisings had seen women and feminists at the forefront of all kinds of social struggles. People were radicalizing and figuring out, collectively, what it means to fight back.

I can still hear Tito: nena, trust no bank.

In the context of the violent imposition from above of further neoliberal austerity, the abortion fight took on new life and became a leading edge of resistance against the entire social and economic system. On May 14, 2005, the first meeting of the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion took place in Córdoba.

“At this first plenary, over seventy women from different organizations sketched out and gave name and political meaning to the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion that, pushed forward by feminist groups, resolved to advance the construction and strengthening of a critical mass capable of calling for [the now famous three demands:] ‘Sex Education to Decide, Contraception Not to Abort, and Legal Abortion Not to Die.’ [They] publicly and simultaneously launched the campaign in different parts of the country on May 28, along with street actions to collect signatures in favor of legal abortion.”

8Claudia Anzorena and Ruth Zurbriggen, “Trazos de una experiencia de articulación federal y plural por la autonomía de las mujeres: la Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito en Argentina,” prologue to El aborto como derecho de las mujeres. Otra historia es posible, ed. Anzorena and Zurbriggen (Buenos Aires: Herramienta, 2012), 29. Author’s translation.

The National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion emerged out of a diverse national coalition nourished by the history of the struggle for legal abortion in Argentina and the political work that women had been doing for decades, particularly shaped by the experiences of 2001 and 2002.

From its inception, the campaign had constant tablings all over the cities, especially Buenos Aires, which included collecting signatures for the petition and handing out info sheets on congresspeople; it unfurled large banners with messages such as “Not one more woman dead from clandestine abortion” in the middle of intersections; it hosted cultural activities with journalists, writers, dancers, actors, and artists in neighborhoods and at festivals; it organized marches and protests on the streets. Every space was indispensable. Millions were wearing the pañuelo, around their heads, their necks, the handles of their bags, and they were available at every newsstand and corner store. The marea verde, the green tide, was crescendoing.9Mabel Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia: Aborto y feminismo (Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual, 2014), chapter 7.

The campaign presented their collectively drafted and proposed bill to Congress on eight different occasions, beginning in 2005. (In Argentina, legislation presented to the government acquires parliamentary status for only two years. If a bill is not taken up for debate and voting during this time, the proposed legislation expires and must be presented all over again.) The abortion bill failed to reach a vote every time, except for the last two: in 2018 and 2020.

The first time the bill made it onto the floor of Congress, in 2018, was under the center-right government of Mauricio Macri—after twelve years of center-left governance, eight of which were under a woman president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. In a historic victory in June 2018, the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Congress) passed the bill onto the Senate, which voted against it by a narrow margin on August 8 of that year.

Despite the bill’s failure in 2018, it was clear to everybody that the campaign and its mobilizations had acquired a mass character. Abortion became the issue that the streets imposed on society and everyday politics, particularly striking in a deeply Catholic country, where the Catholic Church has direct access to the government and a hand in drafting the laws.

The Church and the Argentinian state have always gone hand-in-hand. While the majority of Argentines are Catholic, the percentage has gone down in the last few decades, with increasing numbers identifying as Evangelicals and other Protestant religions, in line with an overall Latin American trend. The crackdown on reproductive healthcare, including access to birth control and abortion, was and continues to be a critical component of the Church’s persistent program of raising the numbers of Catholics in the country.

During the military dictatorship, the Catholic hierarchy enjoyed a privileged position, and many Catholics, clergy, and civilians alike supported and aided the government in its crimes against humanity, including by covering up information on the whereabouts of the detained–disappeared when their loved ones turned to the Church for help. Questions around the role and involvement of Jorge Bergoglio (Pope Francis) himself in the brutal dictatorship have lingered, as he headed the Jesuit order from 1973 to 1979 and thus was a well known member of the Catholic hierarchy backing the political regime. The dictatorship also targeted hundreds of priests, clergy, and civilians who stood in the tradition of liberation theology and against the unfolding horrors. Catholic liberation theologists who worked with the poor were labeled dangerous Marxists/communists—“enemies who misinterpreted Catholic doctrine”—and massacred in the name of “purifying” Argentinian Catholicism of ‘compromised’ Catholics.10Julia G. Young, “The Catholic Church & Argentina’s Dirty War: Victims, Perpetrators, or Witnesses?” Commonweal, September 28, 2015.

During both the 2018 and 2020 abortion campaigns, Pope Francis issued appeals to voting representatives and backed the Church’s central role in the anti-abortion campaign and mobilization, which had pañuelos of their own, but in light blue. Though the bill was passed—on what the group Pro-Life Unity said would go down as “one of the most macabre days in recent history”—anti-abortion groups tied to the Church were successful in forcing important concessions, such as around conscientious objection. The Consortium of Catholic Doctors and Catholic Lawyers Corporation, for example, signed onto a statement urging doctors and lawyers to “resist with nobility, firmness, and courage the norm that legalized the abominable crime of abortion.”11Almudena Calatrava, “Argentina’s Abortion Law Enters Force Under Watchful Eyes,” AP News, January 24, 2021; Almudena Calatrava and Débora Rey, “Bill Legalizing Abortion Passed in Pope’s Native Argentina,” AP News, December 30, 2020. Opus Dei and other right-wing Catholic networks have a presence in “ethics committees” in hospitals. What is happening now is a contestation of how and if the law is followed or enforced, which also encompasses continuing the ideological battle.

In the 1990s, the Ni Una Más (Not One More) movement—christened by poet and activist Susana Chávez—was born to raise international awareness around the epidemic of murdered women and girls, usually between 15 and 25 years old, in the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Between 1993 and 2008, around four hundred women and girls were murdered and hundreds more disappeared in Juárez. Since the 1990s, activists have been demanding that the Mexican state implement strategies for preventing violence, as well as conduct adequate investigations into ongoing disappearances, rapes, and murders. A telling note: the use of the Spanish term femicidio, or feminicidio, meaning femicide, originated in Juárez during this period.

In January 2011, Susana Chávez, 36 years old, was found mutilated in Ciudad Juárez.

The mass character achieved by the abortion movement in the lead-up to the presentation of the abortion bill in 2018 in Argentina was catalyzed by the bursting of the Ni Una Menos (Not One Less) movement against femicide onto the political scene in 2015.

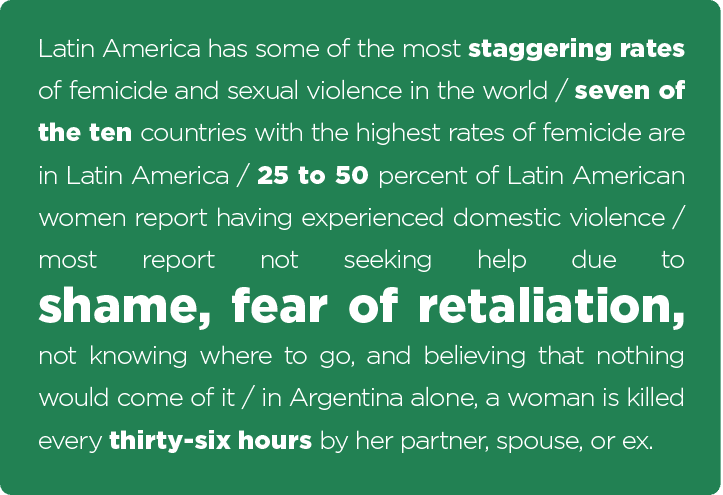

The mass character achieved by the abortion movement in the lead-up to the presentation of the abortion bill in 2018 in Argentina was catalyzed by the bursting of the Ni Una Menos (Not One Less) movement against femicide onto the political scene in 2015. This is, of course, no coincidence. Femicide and abortion are intimately tied together, not just around the fundamental questions of bodily autonomy and the recognition of women’s humanity as whole, individual people, but also by their interplay in the concrete lived experiences of so many of us.

In 2015, the body of Daiana Garcia, 19, was found by the roadside in Llavallol, Buenos Aires Province. Her remains were inside a trash bag. A few months later, after a three-day search, the body of Chiara Paez, 14 and a few weeks pregnant, was found buried in the garden of her boyfriend’s home. He was 16. Chiara had been beaten to death after she was forced to take medication to terminate her pregnancy. Her boyfriend confessed to the murder, as well as to having been helped by his mother.

On the day they found Chiara’s body, Argentinian women and feminists took to the streets, rallying around the slogan and hashtag #NiUnaMenos. Barely twenty-four hours after the march ended, the government announced that a registry of femicides would be set up to compile statistics. Most importantly, the massive turnout showed that looking away, on a societal level, was no longer an option.

In October 2016, the body of 16-year-old Lucía Pérez was found in the coastal city of Mar del Plata. She had been raped and impaled. In response, the Ni Una Menos collective organized the first national women’s mass strike. The strike consisted of a one-hour work and study stoppage in the early afternoon, with protesters dressed in mourning for what came to be known as Black Wednesday. These protests became region-wide and gave the movement a greater international momentum, with street demonstrations also taking place in Chile, Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Spain, and other countries.

The experience of organizing the strike had a profound impact on the collective process of building the Ni Una Menos movement in conjunction with the fight for abortion. In 2017 and 2018, the preparatory assemblies for the feminist strike in Buenos Aires tripled in attendance. The same happened in hundreds of assemblies across the country. This strengthening dynamic developed in terms not only of numbers, but also of politics.

The slogans taken up by the Ni Una Menos collective in Argentina over the course of several years are illustrative. In 2016, their main slogan was “We Want Ourselves Alive”; in 2017, “No More Gender Violence and State Complicity”; and in 2018, “Without Legal Abortion, There Is No Ni Una Menos. No to the Macri–IMF Pact”—a progression reflective of the broadening and deepening of the movement’s horizons, analyses, and connections drawn. As Verónica Gago argues, the feminist movement in Argentina has had the “remarkable capacity to bring together two features often considered anathema to one another: massiveness and radicality.”12Verónica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything (New York: Verso, 2020), 156.

Combined with the organization rooted and built up over years by the national campaign and annual National Women’s Gatherings, Ni Una Menos changed the terrain of struggle.

Combined with the organization rooted and built up over years by the national campaign and annual National Women’s Gatherings, Ni Una Menos changed the terrain of struggle. It gave people the confidence to speak out against issues of gender oppression, as well as raised questions regarding the economic and social system as a whole.

The intersections of gendered violence, both against femicide and state-sanctioned murder against people who are pregnant and do not want to be, were articulated in an insistence that women are full human beings who do not belong to their partners, who have a right to life, health, and their own decisions, however complicated or not. The national campaign was able to seize the opportunity to grow into the powerful, mobilized force of nature that reverberated at every dinner table, every street corner, every seat of Congress.

Susana taught us:

“with your feet you walk

without breaking the memory.”

13Susana Chávez, “Sin romper la memoria,” Primera Tormenta: Poemas de Susana Chávez, May 26, 2004, https://primeratormenta.blogspot.com. Author’s translation.

Not a single clandestine abortion-related death has been recorded since the legalization of abortion in Argentina.14Mariana Iglesias, “Aborto legal: ni una muerta,” Clarín, July 1, 2021. Ni una menos.

When an issue reaches prominence in Argentina, it finds organizational expression very quickly—a dynamic that goes back to the way the civic-ecclesiastical-military dictatorship (1976–83) was overthrown in the late twentieth century. The Argentinian dictatorship, unlike those of other countries in South America, was toppled from below, with a women-led struggle around bodily autonomy and reproductive justice at the forefront of the resistance.

And collective memory is no small thing. Two popular slogans point to this societal understanding of the legacy of the dictatorship: “Ni olvido, ni perdón” (never forgive, never forget) and “Memoria, verdad y justicia” (memory, truth, and justice), with the latter acting as part of the official title of the annual day of remembrance commemorating the victims of the dictatorship.

“Though we cannot predict the world that will be, we can well imagine the one we wish it to be. The right to dream doesn’t appear among the thirty human rights proclaimed by the United Nations at the end of 1948. But, if it weren’t for the right to dream and for the water it gives us to drink, the other rights would die of thirst.

Let us rave madly, then, for a little while. The world, which is upside down, will stand on its feet: …

In Argentina, the locas of the Plaza de Mayo will be an example of mental health, for they refused to forget in the time of obligatory amnesia.”

15Eduardo Galeano, “El derecho de soñar,” El País, December 25, 1996. Author’s translation.

The fourteen women grew to thirty and then seventy and then hundreds and then thousands, generation after generation, mothers, grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and on and on.

On a Thursday of April 1977, around five o’clock in the afternoon, fourteen women between the ages of forty and sixty defied the outlawing of the right to assembly imposed by the civic-ecclesiastical-military dictatorship. They marched, one in front of the other, around the Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires’s central square. They were mothers of those disappeared by the dictatorship, the bloodiest and cruelest in the history of the country and one of the most brutal apparati of state terrorism in the region.

Archived news footage of the day shows the women surrounding a cop in the plaza, all donning around their heads what became their signature white pañuelos. One woman screams at the police officer: “We want to know where our children are, alive or dead! Anguish because we don’t know if they are sick, if they are cold, if they are hungry, we don’t know anything! And despair, sir, because we don’t know who to go to anymore. Consulates! Embassies! Ministries! Churches! Everywhere they close their doors on us!” They marched around the square, circling the presidential palace, national congress, and the central bank, never ceding to the institutions complicit in the sequesters, disappearances, and cold-blooded murders of more than thirty thousand people.16One of the most notorious methods of murder by the dictatorship were death flights, in which prisoners were drugged, stripped naked, and flung out of aircrafts into bodies of water. “Argentina: cumplen Madres de Plaza de Mayo 36 años de lucha,” teleSUR tv, April 30, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3me2wogxNc. They came back the next day. And the next.

The fourteen women grew to thirty and then seventy and then hundreds and then thousands, generation after generation, mothers, grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and on and on, protesting to this day for the safe return of their loved ones. As Mercedes de Meroño, Mother of Plaza de Mayo, remarked: “We never looked for bones or corpses. We looked for them alive, as beautiful as when they were taken.”17Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo, ¡NI UN PASO ATRÁS! 2, no. 7 (April 2012).

Later that year, Azucena Villaflor, Esther Ballestrino, María Ponce de Bianco, and Angela Auad—founders of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo—were kidnapped and murdered.

On the first International Working Women’s Day after the fall of the dictatorship, March 8, 1984—a sunny Thursday, according to records—the first march for legal abortion under formal democracy happened. Pictures from the day include a famous shot of María Elena Oddone, an elegant housewife wearing a tailored white dress with a purse hanging off one shoulder, climbing the steps of the monument of the Congressional Plaza, “as if a Hollywood star receiving her Oscar,” and proudly hoisting her sign up with both hands, à la Norma Rae: No To Motherhood, Yes To Pleasure.18Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia, 269. Other signs in the crowd read: Free Abortion: We Give Birth, We Decide; Rape Is Torture; Decriminalize Abortion; No More Deaths From Illegal Abortions; Free And Conscious Motherhood.

A decade earlier, in 1974, in an effort to double Argentina’s population to 50 million by the end of the twentieth century, President Juan Perón issued a decree restricting the sale of contraceptive pills to the point where they were practically impossible to obtain. The decree required the signatures of three different medical authorities for oral contraceptive prescriptions, launched an anti-contraception educational campaign, and outlawed the distribution of birth control information.19Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia, 215–18; Jonathan Kandell, “Argentina, Hoping to Double Her Population This Century, Is Taking Action to Restrict Birth Control,” New York Times, March 17, 1974.

Perón and his Ministry of Health took it a step further, accusing “nonArgentine interests” of “encouraging birth control, perverting the fundamental maternal role of women, and leading youths astray from their natural duties,” and asserting that foreign foundations were funneling money into Argentina “to sterilize its women.” This was part and parcel of the focus, beginning in the 1960s, on demographic growth and birth rates as cornerstones to Argentina’s nation-building project, in a context where the first combined oral contraceptive pills were being commercialized and their use generalized in the United States, and women of the Global South were being forcibly sterilized by colonial and imperial powers.

These same children that Argentinians were forced to birth and care for were then made to grow up without the parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, friends, teachers, and so many others they might have known and cherished had they not been violently taken by the state. The true value of pregnancy and children to the very nation that waxed poetic about their sanctity was apparent. Among the many large banners carefully crafted and relentlessly carried by the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza during the dictatorship were ones denouncing the conditions of pregnancy and childbirth inside the government’s death camps, including a prominent one that read: Where Are The Hundreds Of Babies Born In Captivity? People were tortured and raped, childbirth occurred in shackles, and newborns were kidnapped never to be returned.20“Nieto 130: ‘La restitución de mi identidad es un homenaje a mis padres,’” El País, June 13, 2019. The policing of reproduction was not, in fact, a question of “life,” but one, precisely, of death.

Many of these babies were then illegally put up for adoption and their identities kept secret. The Association of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, the main organization taking up the search for these children and the restoration of their identities, estimates that over five hundred children were disappeared under these conditions. By June 2019, the identities of one hundred and thirty people had been recovered as children taken from the dictatorship’s camps. The stories of generations of people who have grown up unsure of their family histories and suspecting they are related to the disappeared are widespread, part of the fabric of Argentinian society.

In 1994, almost two decades after the Mothers’ and Grandmothers’ first outing, Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice would coin the concept of reproductive justice in the United States: “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”21“Reproductive Justice,” SisterSong, https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice.

In an echo of Perón’s natalist, misogynist project cloaked in quasi-anti-imperialist rhetoric, in 2018, a well known priest from a villa slum preached that abortion was not a working class issue. He claimed that, actually, “the IMF is abortion,” drawing an equivalence between the demand for abortion rights and IMF austerity as both imposed from the Global North to subordinate our people. As Gago writes, “They ignore and falsify both the historical struggles for abortion and the current state of the feminist movement, where the demand is associated with the desire for a dignified life against neoliberal austerity, and in whose amalgam pañuelazos [protests waving the green handkerchiefs] were carried out in many neighborhoods and slums.”22Gago, Feminist International, 223–24. Emphasis in original.

The Catholic Church’s co-optation of social justice sentiment and language to paint itself as the anticolonial bulwark against the external imposition of abortion (and “gender ideology” more broadly) in Argentina is, of course, laughable. As we well know, the role of the Catholic Church in Latin America has been anything but anticolonial. The real aim is to rebrand traditional family values—anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQ—in shiny twenty-first century packaging. The archbishop of La Plata, for example, went so far as to declare that “the increase in femicides has to do with the disappearance of marriage.” As if husbands, boyfriends, and exes are not the overwhelming perpetrators of gendered violence!

As economic adjustment measures, such as inflation, layoffs, and defunded public services, have grown more severe, so too has the crisis of social reproduction. Women, who are already responsible for most unpaid domestic labor in the home, have had to continue to take on more and more as the gaps in societal provisions have widened, and the burdens on the nuclear family have gotten heavier. In the wake of the severe Argentinian financial crises and the new mass radical feminist movement that has grown in numbers and political vision, in large part due to the very uprisings against neoliberalism, the Church’s attempt to revive the ideology of private family responsibility and traditional gender roles has become a crucial pillar for the anti-abortion right. At the same time, the Church has also billed itself as a provider and distributor of resources for ordinary people, especially in peripheral neighborhoods that often have the highest need for items like food, diapers, milk, and so on. This aid, however, is always conditional, always dependent on the adherence to traditional gender roles, binaries, values, and the obligation of maternity.

Feminism is seen as the internal enemy by the right as well as by certain sections of the Left. In fact, these left-wing tendencies tout similar arguments: that abortion is not a working class issue and to cater to such “niche” and “specialized” issues is a detriment to the “class” struggle. In an interview for Jacobin, published the day before abortion was legalized, Argentinian legislator and activist Ofelia Fernández made sure to clarify that she “[doesn’t] mean to put feminism in a vanguard role either—although many characterize it as fulfilling that role.”23“Argentine Feminists Are About to Win the Fight for Abortion Rights: An Interview with Ofelia Fernández,” Jacobin, December 29, 2020.

On the night of the passage of the abortion bill, I watched aerial videos of the green tide in the plaza and on the streets, chanting in unison: “Down with the patriarchy, which will fall, which will fall! Up with feminism, which will win, which will win!”24The Green Tide, Argentina, December 30, 2020, the night abortion was legalized. The original chant in Spanish is: ¡Abajo el patriarcado, que va a caer, que va a caer! ¡Arriba el feminismo que va a vencer, que va a vencer! “#Argentina| ‘Abajo el patriarcado que va a caer, arriba el feminismo que va a vencer’ esos fueron lo cánticos de miles de argentinas que celebraron la legalización del aborto en su país,” Facebook video by WRadio Ec, December 30, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=219019626464950.

I wept. Call me overly sentimental, but how can you look at that, a collective cry from millions that unrooted one of the official remaining vestiges of the brutal dictatorship that marked our country deeply, and say that they are not at the forefront of struggle? It is a turning away from the people and from reality. Anyone who knows anything about Argentinian history should know better. Memory, truth, justice.

Evel “Beba” de Petrini, mother of Osvaldo Sergio Petrini, disappeared at 21, remarked: “I think that the Mothers’ fundamental step was to make everybody a Mother, and to make Mothers of us all. That joined us in struggle. Not asking for the personal, not asking for the biological child, but making everyone our children.”25Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo, ¡NI UN PASO ATRÁS! 8 This expanded notion of community, care, and kinship—woven together by the fight for justice and a democratic society in which we all thrive, and against the confines and violence of the nuclear family—is part of the political legacy and tradition of Argentinian feminism, as well as feminism more broadly. It is a lesson that emerges over and over in any meaningful struggle, and one that has recurred in the contemporary battle for abortion rights and reproductive justice in Argentina.

In a striking example of this political understanding, daughters of some of the men responsible for carrying out the brutality of the dictatorship came forward at the Ni Una Menos march on June 3, 2017. They spoke of their childhoods, denounced their fathers, and publicly contested the legal provision banning family members from testifying against each other.26“The collective of the former daughters of genociders presented an amendment in 2017 for those prohibitions to be removed ‘in the case of crimes against humanity, thus enabling the sons, daughters, and family members of genociders, who voluntarily wish to testify, to be able to contribute to the legal case in that way.’ Ultimately, the modification [to this article of the Argentina Legal Code] was not approved.” Gago, Feminist International, 258 State terrorism became a salient public thread running through the dictatorship’s concentration camps and the family home. As Gago has noted, “this idea supposes that there is no state terrorism without its intimate ties to the patriarchal family…It is precisely that border between domestic life and public life that disappears”—a key feminist contention.

This defiant defiliation was an intervention into the collective and living memory of an entire society, and showed that generational continuity, as the Madres and Abuelas taught us, need not be biological. The feminists in the streets for Ni Una Menos, abortion, justice, and against austerity and imperialism, are all children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of the Madres and Abuelas of the Plaza. Put another way, “rebellion [is posited] as that which creates kinship”—a queering of memory and affective ties, and a contestation of political spirituality.27Gago, Feminist International, 110, 221–23.

In 1983, the dictatorship was overthrown by mass uprisings from below, led by the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza relentless in their documentation of their disappeared loved ones, demands for their safe return, and denunciations of those responsible.

Following the dictatorship, Argentina entered a period of formal democratization. But when you have a people, whose collective memory is intimately tied to a period of brutal dictatorship, it is not so easy to ignore the rights you don’t get back during the process of democratic reconstitution. As the Argentinian saying goes, “With democracy, we eat, we heal, we educate, but we don’t abort.” Both under the dictatorship and under formal democracy, abortions continued to be had in clandestine conditions, often without dignity.

There have always been some—usually upper-class, urban, white, well connected, cis, straight, able-bodied women—able to abort safely despite technical (il)legality. To legalize abortion, to make it safe and free and accessible, is actually about democratizing the right to control one’s own body. This has never been lost on the Argentinian feminist movement, which sees itself as a continuation, as struggling in the tradition, of the Madres and the Abuelas.

The abortion movement’s beloved green pañuelo has as its logo and central image the white pañuelo of the Mothers and Grandmothers, drawn as if around an invisible head, ballooned at the top and crisscrossed at the ends—a deliberate nod to those who came before, the disappeared–murdered, the exiled, all those still here, and all those still waiting.

What is our relationship to history? Do we belong to it, or is it ours? Are we in it? Does it run through us, spilling out like water, or blood?

28Tracy K. Smith, introduction to Generations: A Memoir, by Lucille Clifton (New York: New York Review of Books, 2021).

We can understand history because we have made it—and we have not made it alone. Walter Benjamin contended that “every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.”29Benjamin, “On the Concept of History.” Well, we must cling.

Notes & References

* This title is taken from the dedication to María Florencia Alcaraz’s ¡Que sea ley! La lucha de los feminismos por el aborto legal (Buenos Aires: Editorial Marea, 2018).

- Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm.

- Jennifer Baumgardner, “Twice Is a Spanking,” in Abortion Under Attack, ed. Krista Jacob (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2006). Thank you to Michael Dola for pointing me to this essay.

- It’s law, my love, it’s law. Author’s translation.

- Subcomandante Marcos, “Today, Eighty-five Years Later, History Repeats Itself” (speech, inaugural ceremony of the American Planning of the Intercontinental Meeting for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism, April 6, 1996), https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/subcomandante-marcos-our-word-is-our-weapon#toc40.

- Daniel Politi and Ernesto Londoño, “Argentina Legalizes Abortion, a Milestone in a Conservative Region,” New York Times, December 30, 2020.

- Nora Caplan-Bricker, “Why Are Abortions Performed in Clinics?” Slate, November 16, 2015.

- There has been much debate within the campaign around codifying a time frame in which an abortion must be received. Though similar to a traditional abortion waiting period in other countries, activists in the campaign saw the inclusion of a time window as necessary to ensure that requested abortions were performed in a timely manner. The campaign’s original proposal was for a five-day window. The anti-abortion right, however, was able to successfully extend the proposed time frame, with the idea that more time means higher chances of dissuading people from ultimately getting their abortions.

- Claudia Anzorena and Ruth Zurbriggen, “Trazos de una experiencia de articulación federal y plural por la autonomía de las mujeres: la Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito en Argentina,” prologue to El aborto como derecho de las mujeres. Otra historia es posible, ed. Anzorena and Zurbriggen (Buenos Aires: Herramienta, 2012), 29. Author’s translation.

- Mabel Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia: Aborto y feminismo (Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual, 2014), chapter 7.

- Julia G. Young, “The Catholic Church & Argentina’s Dirty War: Victims, Perpetrators, or Witnesses?” Commonweal, September 28, 2015.

- Almudena Calatrava, “Argentina’s Abortion Law Enters Force Under Watchful Eyes,” AP News, January 24, 2021; Almudena Calatrava and Débora Rey, “Bill Legalizing Abortion Passed in Pope’s Native Argentina,” AP News, December 30, 2020.

- Verónica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything (New York: Verso, 2020), 156.

- Susana Chávez, “Sin romper la memoria,” Primera Tormenta: Poemas de Susana Chávez, May 26, 2004, https://primeratormenta.blogspot.com. Author’s translation.

- Mariana Iglesias, “Aborto legal: ni una muerta,” Clarín, July 1, 2021.

- Eduardo Galeano, “El derecho de soñar,” El País, December 25, 1996. Author’s translation.

- One of the most notorious methods of murder by the dictatorship were death flights, in which prisoners were drugged, stripped naked, and flung out of aircrafts into bodies of water. “Argentina: cumplen Madres de Plaza de Mayo 36 años de lucha,” teleSUR tv, April 30, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3me2wogxNc.

- Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo, ¡NI UN PASO ATRÁS! 2, no. 7 (April 2012).

- Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia, 269.

- Bellucci, Historia de una desobediencia, 215–18; Jonathan Kandell, “Argentina, Hoping to Double Her Population This Century, Is Taking Action to Restrict Birth Control,” New York Times, March 17, 1974.

- “Nieto 130: ‘La restitución de mi identidad es un homenaje a mis padres,’” El País, June 13, 2019.

- “Reproductive Justice,” SisterSong, https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice.

- Gago, Feminist International, 223–24. Emphasis in original.

- “Argentine Feminists Are About to Win the Fight for Abortion Rights: An Interview with Ofelia Fernández,” Jacobin, December 29, 2020.

- The Green Tide, Argentina, December 30, 2020, the night abortion was legalized. The original chant in Spanish is: ¡Abajo el patriarcado, que va a caer, que va a caer! ¡Arriba el feminismo que va a vencer, que va a vencer! “#Argentina| ‘Abajo el patriarcado que va a caer, arriba el feminismo que va a vencer’ esos fueron lo cánticos de miles de argentinas que celebraron la legalización del aborto en su país,” Facebook video by WRadio Ec, December 30, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=219019626464950.

- Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo, ¡NI UN PASO ATRÁS! 8.

- “The collective of the former daughters of genociders presented an amendment in 2017 for those prohibitions to be removed ‘in the case of crimes against humanity, thus enabling the sons, daughters, and family members of genociders, who voluntarily wish to testify, to be able to contribute to the legal case in that way.’ Ultimately, the modification [to this article of the Argentina Legal Code] was not approved.” Gago, Feminist International, 258.

- Gago, Feminist International, 110, 221–23.

- Tracy K. Smith, introduction to Generations: A Memoir, by Lucille Clifton (New York: New York Review of Books, 2021).

- Benjamin, “On the Concept of History.”