“This is about territory,” Leonardo Vilchis emphasized to a packed room at the People’s Forum in New York City on October 2, 2024. Over two hundred people hungry for wisdom on tenant organizing came to celebrate the release of Abolish Rent: How Tenants Can End the Housing Crisis. Vilchis and his coauthor, fellow cofounder of the Los Angeles Tenant Union (LATU) Tracy Rosenthal, offered an intervention into our thinking from their years building LATU. For Rosenthal and Vilchis, tenant organizing is a spatial struggle—the struggle for territory—tasked with building durable working-class organizations that support tenants in exercising control over the spaces in which we live. The conversation, which featured Ben Mabie (Abolish Rent’s editor and a Crown Heights Tenant Union member) and Khadija Haynes (tenant organizer and member of Brooklyn Eviction Defense) reflected the style of the book itself: part manifesto, part storytelling, and part organizing manual. Most of the questions from the audience were organizing questions, asking the panel for advice on how to build power in their buildings and across their neighborhoods. This book comes from inside the tenant movement, and the tenant unions and other working-class organizations across the country attending its book events have received it as such.

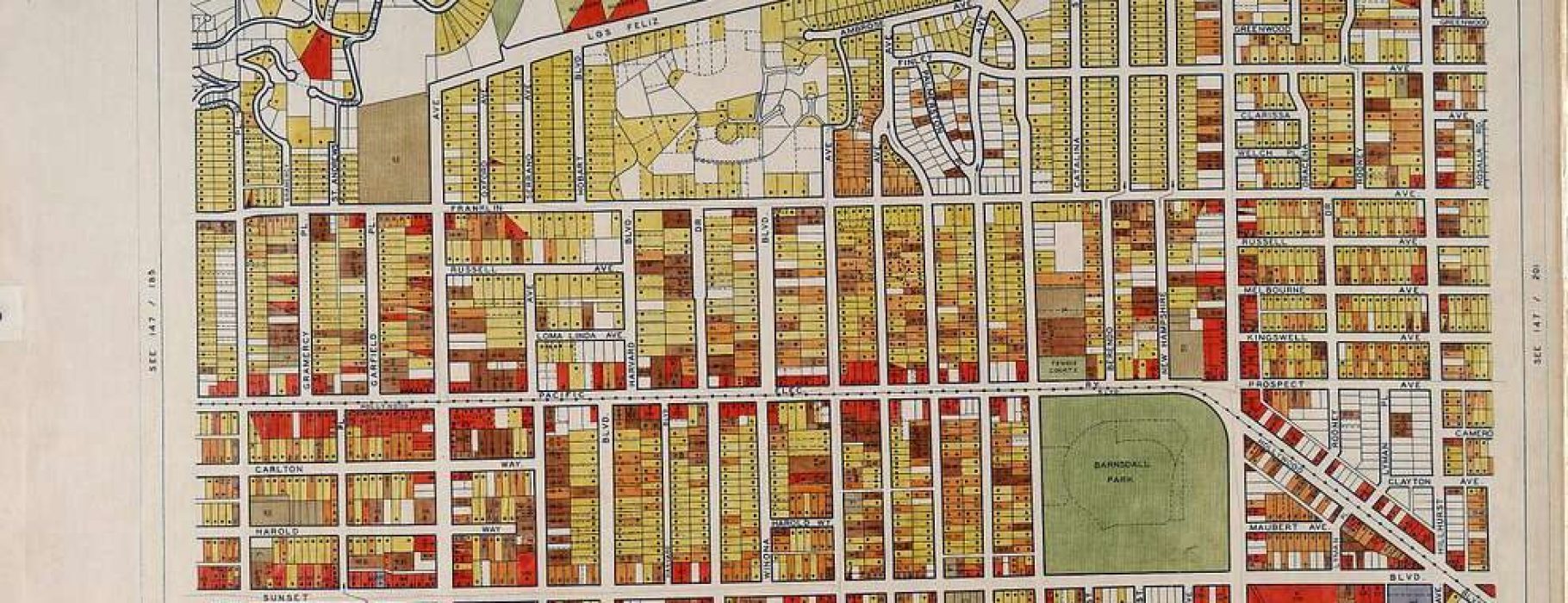

I read Abolish Rent with three hats on: as a tenant currently on a rent strike with my neighbors, as a tenant organizer in the Crown Heights Tenant Union, and as a geographer. This book is a work of public geographic thought, answering Mariame Kaba and Kelley Hayes’ call for organizers to “Think Like [Geographers],” a chapter from their recent book Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care.1Kelly Hayes and Mariam Kaba, Let this Radicalize You:Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care (Chicago: Haymarket, 2023). At its heart, what Abolish Rent offers is a framing of spatial struggle: how we reclaim, socially reproduce, and transform space for purposes other than capital accumulation. The authors’ diagnosis of the problems of dispossession are spatial; their definition of gentrification is the displacement and replacement of the poor for profit.2Tracy Rosenthal and Leonardo Vilchis, Abolish Rent: How Tenants Can End the Housing Crisis (Chicago: Haymarket, 2024), 93. Tenants are displaced through harassment, lack of repairs, offering cash for keys, rezoning, condo conversions, demolition, court-ordered eviction, and through the threat of state violence. Since the threat of displacement is a violent, spatial threat of removal, Rosenthal and Vilchis articulate their solutions in spatial terms. Rather than fighting for our homes through legislation or policy enforcement, the thrust of this book conceptualizes tenant struggle through placemaking and the creation of zones of working class control—that is, through territory.

Throughout the book, the authors tell stories of tenants in the Los Angeles Tenant Union who engage in spatial processes. Conceptualizing territory has long been an object of inquiry in geography, and although the authors do not define their use of the term or its genealogy, their descriptions of territory evoke its use in Indigenous social movements in Latin American such as the autonomous zones of the Zapatistas and the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, MST). These movements conceive of territory not as sanctioned by the state or conferring colonial power, but as produced relationally through the appropriation of space for political struggle.3Sam Halvorson, “Decolonising territory: Dialogues with Latin American knowledges and grassroots strategies,” Progress in Human Geography 43, no. 5 (2018): 790–814, https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325187776. In the case of the US tenant movement, Rosenthal and Vilchis argue that autonomous zones of self-governance are established through the occupation of land, public space, and buildings. They conceptualize the rent strike as an occupation to reclaim and remake the territory of our homes.4Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 101 They argue that the process of organizing changes tenants’ relationships to their homes from a passive acceptance of the home as a site of extraction and atomization into an active engagement that establishes and grows working-class control of our blocks and buildings. For Rosenthal and Vilchis, occupying homes, gardens, alleys, and other shared spaces is a transformative process through which territory is created. The authors describe working class territories as places where residents refuse extraction and state violence by both engaging in new ways of co-inhabiting space and practicing community defense to protect one another from threats ranging from criminalization to eviction to climate disasters. By situating class conflict in terms of territory, Abolish Rent offers openings to tenant organizers by framing the fight for working-class control over space as a struggle to create autonomous territories with collectivity, care, and militancy as organizing principles.

The book opens with the “manifesto” in the first chapter, “Rent Is The Crisis,” followed by a chapter of historical context entitled “The War on Tenants,” where the authors lay out their analysis of the so-called housing crisis. In fact, despite using this terminology in the title of the book, they waste no time debunking the popular framing of a “housing crisis.” They define the real estate industry as relying, “on privatizing a common resource (land), hoarding a common need (housing), blocking public interventions or competition, and maintaining a captive market of tenants to exploit and dominate.”5Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 12. The housing system, then, isn’t actually designed to provide quality housing to tenants, it’s designed to “maximize profits and to extract the most rent.”6Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 11. So, from the point of view of landlords, developers, and real estate speculators, the system is working just fine and it’s not housing that is in crisis—it’s tenants. The authors explain that this is why tenants (and not housing) are the subject of their organizing in the Los Angeles Tenant Union. They advocate for an expansive use of the word tenant beyond only renters to anyone currently housed or unhoused who doesn’t control their shelter, who inhabits but doesn’t own.7Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 12. Tenant organizing then, is changing the terms of our inhabitation by reclaiming control of the space in which we live.

The shift proposed by Rosenthal and Vilchis from an analysis of the housing market to a people-centered analysis is a thread throughout the book, as the authors consistently bridge their understanding of the capitalist housing system to the lived experience of poor and working class tenants. The authors offer various conceptualizations of rent, including “a fine for having a human need,” “the gap between tenants’ needs and landlords’ demands,” and a “monthly tribute” for shelter, all of which are centered in the experiences of the poor and working class.8Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 14, 57. They argue, “rent is a power relation that produces inequality, traps us in poverty, and denies us the capacity to live as we choose. Rent is exploitation and domination. It separates us from our neighbors and alienates us from the places we live. It is the engine that turns a human need into a product to be exploited, bet on, banked. Rent is the crisis. We pay the price of rent in money, but also in our dignity.”9Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 12–13.

While the first of every month when the rent is due is a humiliating and stressful time for tenants who “pay rent at the peril of our need and at the barrel of a gun,” it is also an opportunity for organizing, collective action, and collective refusal.10Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 13. Whereas organizing for “housing solutions” allows for continued atomization and extraction through individualized fixes, collective action and collective refusal necessitates a tenant-centered analysis grounded in changing the ways that tenants inhabit, produce, and reclaim the space of their homes. This collectivity does not happen automatically, as the authors remind us, “the shared proximity and vulnerability of tenancy – the exploitation and domination of rent – does not necessarily impel us to organize. We have to make an active effort.”11Rosenthal and Vilchis, Abolish Rent, 55. According to Rosenthal and Vilchis, that effort lies in the collective transformation of tenants’ relationships to the space of their homes from acquiescing to extraction into resisting through occupation. After asserting why a tenant-centered analysis is required for tenant organizing during the “manifesto” chapters and situating tenancy within a historical context of “One Hundred Years of Real Estate Rule,” they illustrate the necessity of this claim with stories of territory creation in the book’s latter chapters.