H. Rap Brown, Jamil Al-Amin, and the Perils of Forgetting

Interview With Arun Kundnani

February 11, 2025

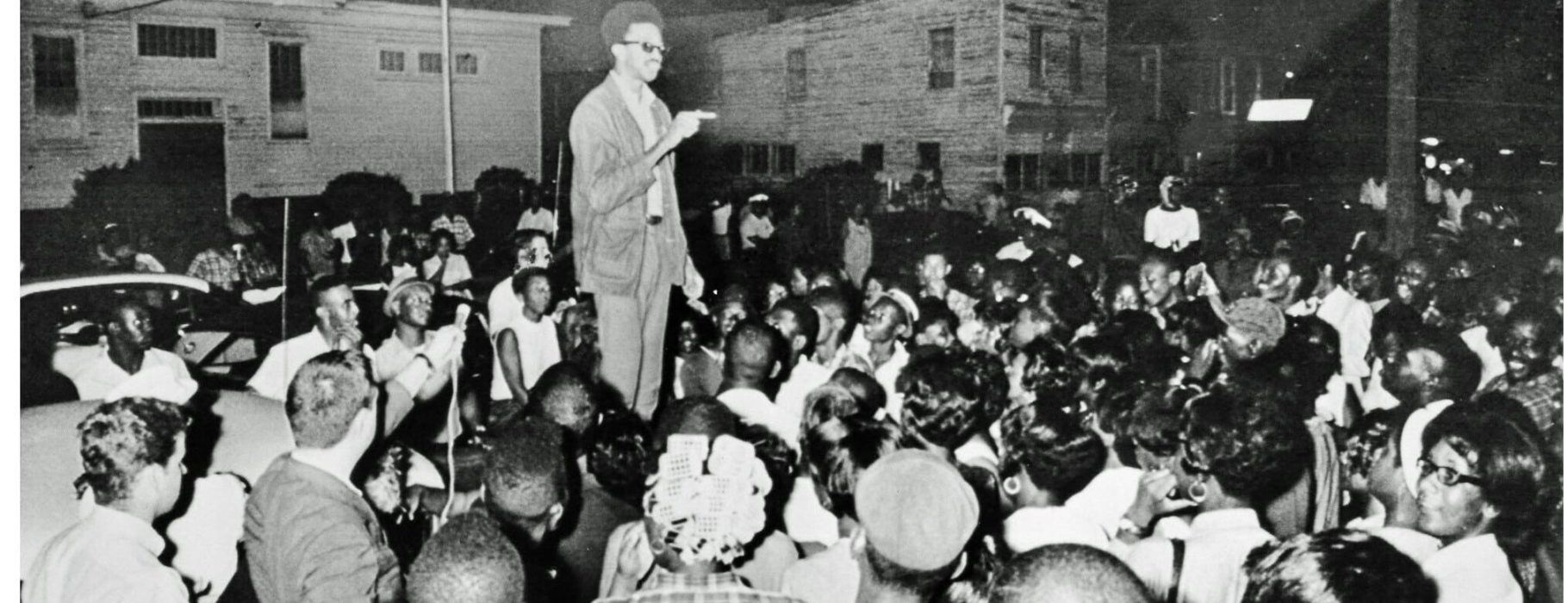

In the late 1960s, H. Rap Brown’s incendiary speeches lit up the US civil rights movement—which, though instrumental in passing such groundbreaking legislation as the Voting and Civil Rights Acts, had only begun to confront the racism embedded in the US government, as well as in US society. Whether Americans thrilled or shuddered to his words, Rap Brown became a mainstream news headliner, remembered for declarations like, “If America don’t come around, we’re gonna burn it down” and “Violence is as American as cherry pie.”

These words, especially coming from H. Rap Brown, Chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)—a formidable Black, antiwar organization at the time—caught the eye of law enforcement agencies, notably J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, whose Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) was already busy “neutralizing” liberation movements like the Black Panther Party. In 1971, COINTELPRO succeeded in sending Rap to prison for five years on a phony robbery charge. Then, in prison, Rap converted to Islam. After that, he seems to have largely fallen out of media headlines and disappeared from the world.

H. Rap Brown became Imam Jamil Abdullah Amin. For decades, he ministered to Muslim communities around Atlanta until 2000, when he was charged with the shooting death of a Georgia sheriff’s deputy. Though maintaining his innocence, in 2002, Imam Jamil was convicted and began serving a life-without-parole sentence inside federal supermax prisons. In 2014, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, an incurable cancer, for which he has received little treatment. Given all that has happened in his life, it’s quietly astounding that so little of Jamil Al-Amin is reflected in the public record. But due to the work of author and activist Arun Kundnani, we are about to find out much more about this man.

Kundnani decided to write a book about Jamil Al-Amin in 2014, after publishing The Muslims Are Coming! Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror. In researching Muslims, he came across the case of Luqman Abdullah, a Black imam in Detroit, killed in a 2009 FBI raid, whose close association with Imam Jamil had attracted the FBI’s attention. Working on a follow-up article for the Nation, Kundnani talked to Karima Al-Amin, Imam Jamil’s wife since 1968—and began to see in Rap Brown/Jamil Al-Amin a thread connecting the US war on terror, Black radicalism, political Islam, government surveillance, and even radicalism itself.

So, Kundnani read acres of books and declassified documents; he talked with scores of people. Most of all, he needed to talk with Imam Jamil. In 2017, he applied to the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) for an in-person interview, but was refused. Kundnani went to the American Civil Liberties Union, which was unable to help, so he started a petition, garnering signatures of hundreds of civil rights historians who attested to the fact that Imam Jamil Al-Amin and his knowledge of politics and history are invaluable. Still the BOP refused. In 2020, Kundnani went to First Amendment clinics at Cornell and Arizona State University, which together mounted a legal challenge, arguing that it was a violation of Kundnani’s First Amendment rights to deny him access based on the content of the imam’s speech. They presented the complaint to the Department of Justice and threatened to take the BOP to court. At this point, the feds agreed to allow Kundnani two in-person interviews at the US Penitentiary (USP), Tucson, in August 2021.

Now, in 2025, Kundnani is finishing his book, whose working title is Rise in Fire: H. Rap Brown, Jamil Al-Amin, and the Long Revolution, slated for publication by Doubleday in 2026. His work coming to a close, Kundnani needed to interview Imam Jamil one last time. Again after much struggle, he was granted interviews on January 7 and 8 of this year, at USP Tucson. By now, however, the Imam had developed a large facial growth, which remains undiagnosed and may be related to his cancer.

I asked Kundnani about visiting Imam Jamil—and what we need to know about him.

Arun Kundnani is a writer based in Philadelphia. His most recent book is Homeland Security: Myths and Monsters (Common Notions, 2024).

He’s quite a mild-mannered guy, not effusive. That’s pretty surprising. He’s got this aura of substance about him; his words seem to carry a lot of weight. He speaks slowly and thoughtfully—which may not be how you’d imagine him, if you’d seen those videos of him from the late 1960s.

When I first met him, he’d been in prison twenty-one years. He’d spent five or so of those years in the ADX Florence supermax prison in Colorado, where he was buried underground in a cramped cell with the most minimal human contact, in a situation where many people develop permanent mental health issues. It’s considered psychological torture. So I was wondering how he would be, psychologically. But he was 100 percent as sharp as he would have come across in the videos of him as a young man.

The kind of conversations he was able to have would range over, not just his personal story and the movements he’d participated in, but also references to social theorists like Frantz Fanon and Ibn Khaldun. He was able to weave his story into those ideas, which was very impressive. And he’s funny. Remarkably, he was able to have quite a lot of humor in our conversations.

I’m not Muslim, right? So one thing would be his gentle mocking of me for not believing in God. We’d have funny exchanges about that. Of course, at the same time, he’s serious about wanting to persuade me. Also, the last time I saw him, we were talking about how, when he became Chair of SNCC in May 1967, powerful forces were gunning for him, because SNCC was the leading Black Power and antiwar organization. He was under heavy surveillance and might have reasonably feared for his life. So I asked Imam Jamil if, in that moment, he felt fear. And he did this physical thing of turning to me and smiling as if to say [mugging]: I’M H. RAP BROWN—I DON’T FEEL FEAR! It was funny.

You’re right that there’s this phenomenon of people coming out of the Black Power movements converting to Islam in the early 1970s. To understand that, you need to go back to 1967, ’68, ’69, when people think: The Revolution is around the corner! This whole generation of people like Rap Brown, in their mid-20s, feel the world’s about to change in this radical direction. And then that doesn’t happen.

Instead, you get Richard Nixon and law-and-order politics. There’s a moment of asking, “What went wrong?” The conclusion that I think Imam Jamil and a lot of others come to is that there was a kind of emptiness at the core of secular Black radicalism, a sense of a missing spirituality, a moral core. People like Rap Brown, especially in the South, were brought up in the Black church. He’d say that a deep-seated sense of spirituality was inculcated in him, especially by his mother. But by the time they’re in their late teens or 20s, they mostly throw that out because it’s Christianity, which feels conservative and like an agent of white supremacy. Yet there’s still that hunger for some kind of spirituality.

Many Africans trafficked as enslaved people were Muslims, so Islam has an authentic connection back to Africa. Islam seems to align with the Black Power belief in self-defense as well. It connects Black Americans to struggles of Africans and Asians around the world. Also in the early ’70s, many radicals were discovering the details of COINTELPRO and the extent to which people in their circle may have been informants, or discovering that more Black people than they expected are willing to accommodate themselves to the system. Islam, I think, offers itself as an answer—that, without a spiritual core tied to the Black struggle, people will be weak and seduced into not siding with the revolution. That line about Allah not challenging the condition of a people until they change themselves speaks exactly to that. So the revolution has to be postponed until we’ve worked to turn ourselves into the raw material capable of a revolution.

Imam Jamil says that Islam is able to make people COINTELPRO-proof. He means the attempt to turn Muslims into informants won’t work if they have the discipline that comes from a strong relationship to God. The turn to Islam also fits with a broader cultural trend among radicals in the early 1970s, many of whom turned inward, living in communes, for example. It’s postponing the revolution until we’ve worked on ourselves.

From one angle, that’s a conservative position, because it’s saying the revolution is no longer the immediate goal. But from another angle, you can see how it’s a necessary and genuine attempt to move forward. What it means in practice for the short-to-medium term is an Islam that’s quiescent: Don’t do political advocacy until you’ve done your own process of moral self-rectification. In that sense, it’s quite different from the political orientation of some Islamic movements active in places like Pakistan or Egypt then. There, the idea is, “Reform yourself individually and society politically at the same time; you don’t have to get one right before you move on to the next.” The people saying, “No political advocacy until you’re a perfect Muslim,” are the Saudis, the most conservative influence in the Islamic world.

I asked Imam Jamil about that and his view was that what’s practical in Egypt or Pakistan—which are majority-Muslim countries—is not practical with formerly enslaved people in the United States. He thinks there’s a lot more moral development work that needs to happen before we’re ready to move to the next political level.

This is one of the fascinating things about this story. He goes from secular, leftist politics to an Islamic politics. That’s a dramatic ideological change, but there’s all kinds of continuities as well. The ideological change hides those continuities, but they’re there. The antidrug work Imam Jamil was doing in the West End of Atlanta, for example, doesn’t start after he becomes a Muslim; he was doing that same work in New York City before he was a Muslim. Similarly, the transnational connections of Black Power politics continue in a new form with Islam.

So Imam Jamil travels to Pakistan, Sudan, and Saudi Arabia—Islam provides this way to imagine an international geography of Muslim struggle. But it’s not absolutely different from the leftist idea of internationalism that he had before he became Muslim, where he saw Black struggle in the United States as an anticolonial struggle connecting with anticolonial struggles in Puerto Rico and Palestine and Southern Africa and Vietnam and so on. There’s more religious elements to secular leftist politics, and more things that look like leftist radical politics in Islam than you’d expect.

It’s absolutely remarkable to me that this guy, who was a household name in the late 1960s, early ’70s, has been almost completely forgotten, erased. Even though there’s a lot of new books that have come out about the Black Power movement in the last ten to twenty years, you’d be lucky to find even a mention of H. Rap Brown. If you did, it’s maybe one sentence, as often as not, quite disparaging. People who’ve heard about him usually assume he’s dead.

There’s been several iterations of forgetting. If you go back to 1971, he’s on the FBI’s Most Wanted list and he’s arrested in New York City, purportedly for robbing a bar. But Rap Brown wasn’t robbing the bar; he was doing the antidrug work that he would go on to do for decades. Based on my research, he was actually hanging around down the street. Meanwhile, a group called the Liberators, with whom Rap had been working, had gone into the bar to challenge the drug dealers operating there. As they were leaving the bar, NYPD officers confronted them and there was a shootout. That’s when cops chased Rap up to a rooftop of a nearby building and shot him.

But the way it’s presented by the New York Police Department is that he was carrying out a robbery of a bar. Even at that point, the feel is like, “Oh yeah, remember that guy, H. Rap Brown? He used to be all Black Power; now he’s just robbing bars.” That’s the first kind of erasure. Then, when he becomes a Muslim later that year in prison, a significant number of people who looked up to him as a Black revolutionary thought that his conversion meant that he’d abandoned his politics and was now a conservative, religious guy. That’s the second level at which he’s forgotten. To some SNCC veterans, that moment seemed like, “Oh, you’re leaving the SNCC community?” Those people who held him as a figure of importance, no longer did so.

The Panther thing is a bit more complicated. In the beginning of 1968, there’s talk of trying to form some kind of unified Black Power organization or a coalition between SNCC and the Panthers, the two most prominent Black Power organizations. SNCC, in Lowndes County, Alabama, had originally come up with the Panther concept, anyway, so there was a logic from that point of view. By early 1968, the Panthers were the larger but also much younger organization. So there were good reasons to find some way of combining.

So Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) and Rap Brown go to California. They’re speaking at the Free Huey rallies, meeting with the West Coast Panthers, and starting to explore the possibilities. Then, the Oakland Panthers announce that they’ve appointed some leading SNCC people to honorary positions in the Panthers. So, Rap is appointed Minister of Justice. But it’s a unilateral thing, not the result of some discussion. Rap was never a member of the Black Panther Party, and never asked to be the Minister of Justice.

Later, in the summer of ’68, some of the Oakland Panthers come to New York City to meet with SNCC people, and things don’t go well. Someone pulls a gun on Jim Forman, a SNCC leader. That’s the end of any possibility of unification or coalition. Even so, the Oakland Panthers remain respectful to Rap Brown.

Yeah. Basically, back in the summer of ’67, you get all these uprisings across US cities; the biggest ones are in Newark and Detroit. On the worst night of the Detroit uprising, President Lyndon B. Johnson calls this meeting in the White House. He’s got FBI director J. Edgar Hoover there and a host of other senior government people. They’re trying to figure out what the hell is going on. Johnson’s point of view is: “I’m the guy that did the Civil Rights Act; I got Voting Rights through; I’m the doing the war on poverty—I don’t understand why people are still frustrated; they couldn’t have had a better deal than me.” So, on that basis, he concludes these can’t be spontaneous uprisings born of frustration; they must be the result of an organized conspiracy and that communists are probably involved.

This is what he’s saying to Hoover, whose perspective is: “There isn’t any evidence of an organized conspiracy. These acts of violence seem to start spontaneously when the police treat people badly.” At least Hoover is able to be that accurate, you know? But he also knows that he’s got to give Johnson something, so he says: “Well, there’s this one guy, H. Rap Brown, who’s been going around the country since he was elected Chair of SNCC, giving these incendiary speeches. He could be a factor.” The other Black Power leader who might have been blamed, Stokely Carmichael, is out of the country, so it all falls on Rap’s head.

That same night, Rap’s speaking in Cambridge, Maryland. Later that night, the Black neighborhood there is burned down, so that gets spun as proof that Rap is inciting riots. But what’s really happened is, some kids have set fire to a school. Actually, they’ve set fire to that school every few weeks in Cambridge because they hate it; it’s a dilapidated, segregated school and symbolizes the inequality those Black kids have in that city.

So every few weeks, these teenagers set fire to that school, then the firefighters come put it out—normally, that’s just another Saturday night, right? But what happens the night Rap’s there is that the firefighters say, “We’re not putting that fire out.” And they stop volunteer firefighters from the Black neighborhood from getting hoses to put it out. So the fire keeps going and it burns down the whole Black business area. Then—because Rap Brown had happened to give a speech in that neighborhood earlier that evening—it’s Rap Brown incited the riot. That’s their charge against him.

Moreover, the Maryland prosecutor deliberately adds the charge that Rap was actually there setting fire to the school. They have no evidence for that but they want to make the indictment serious enough to get the federal level involved. Because when Rap leaves Maryland later that night to go to DC, it triggers a federal unlawful flight charge. So then Rap’s being hunted by the FBI.

When Rap’s lawyer, William Kunstler, finds out there’s an FBI manhunt, he says, “You don’t need an FBI manhunt; he’s quite happy to give himself up; we’ll bring him to the FBI office in New York tomorrow morning.” But the government doesn’t want that; they want this drama: We’re tracking down this fleeing inciter and arsonist—now, we’ve captured him. So they arrest him at the DC airport as he’s on his way to New York to turn himself in. The story presented by Hoover and Johnson is, “The riots were caused by this Rap Brown, going around the country, telling people to riot. We need new legislation to deal with people like this.”

So, Congress passes this legislation. The title has the word riot in it, but not H. Rap Brown. It basically criminalizes travel between states for the purpose of inciting a riot. Informally, it gets called the H. Rap Brown Law. It’s still in existence and used sometimes to go after political radicals.

In 2002, he was convicted of shooting two sheriff’s deputies, one of whom was killed. They were in his neighborhood in Atlanta on March 16, 2000, with a warrant originating from an incident the previous year when Al-Amin was stopped and charged with driving a stolen car and impersonating a law enforcement officer. These two charges were subsequently dropped.

That’s essentially what was presented to the jury. It seems like a case having nothing to do with the federal government, except for the FBI, a few days after the shooting, arresting Al-Amin in Alabama. He’d fled there, thinking the Atlanta shootout was actually done by local drug dealers who were gunning for him. The next morning, he discovered he was again the target of an FBI manhunt. But what we know is, throughout his life, including in the 1990s and up to the day of the 2000 shooting, the FBI were paying informants to spy on Jamil Al-Amin. We’ve got ample Freedom of Information paperwork documenting this.

After the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, there’s also this idea taking hold in the national security world that Islam is the new threat. So, who are they going to investigate? Jamil Al-Amin, right? Because he’s traveling to places like Sudan and Pakistan. He’s a leader, not just of the National Community, his own Black Muslim organization, but he’s also prominent in the leadership of other national Muslim organizations. He must have seemed like a bridging figure between the older revolutionary threats from the Black Power days and the emerging Islamic threat of the 1990s; between African-American Muslims and Muslims with origins in the Middle East and South Asia.

If you look at some of the FBI documents around Imam Jamil’s arrest in Alabama, they refer to him as H. Rap Brown. That tells you there’s an institutional legacy in the FBI: We might have forgotten him, but they remember him and still think of him as that Black ’60s revolutionary, one of the five people at the top of their list in Hoover’s famous August 1967 COINTELPRO memo, which escalates the targeting of Black revolutionaries.

From the internal FBI documents I’ve seen, you get the sense that, among agents, being “the guy who arrested H. Rap Brown” is still, in 2000, something of a prize, the kind of thing you might brag about for years afterward. I think that means you don’t need an organized conspiracy to incriminate H. Rap Brown; you just need a load of people who are highly incentivized to break the rules a little to get a conviction.

It’s not just the FBI. There’s the Atlanta Police Department, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation—that’s how you end up with a case that takes the form this does. You can get into a lot of detail on the flaws in the prosecution, but this is the simplest way to understand why the prosecution doesn’t hold up. If you take a look at the warrant that’s issued for Al-Amin’s arrest the month before the shooting takes place, it wrongly describes Imam Jamil as having gray eyes.

A week after that March 2000 shooting happens, the deputy who survives is interviewed by detectives and is recorded describing the perpetrator, saying, “My mom always said, ‘look a man in the eye’… I looked at him in his eyes. I remember them gray eyes.” And he repeats this in the same way at trial in 2002.

Now, Imam Jamil doesn’t have gray eyes; he has brown eyes. He would also have been wearing glasses. But what’s significant here is not the mistaken identification. It’s that the mistaken identification in the warrant issued before the shooting has exactly the same mistake as in the deputy’s testimony. It’s like when two kids take a test in school and both get the answer wrong in the same weird way: right there, you know that one copied the other. In Al-Amin’s case, it immediately tells us that the deputy wasn’t recounting what he actually remembered that night; he was tailoring his statement to what he believed Imam Jamil looked like, based on the inaccurate warrant. That should tell you there’s been an attempt to manipulate the evidence to get a conviction, which should get you to reasonable doubt—the basis to not convict someone.

Historically, the organization focused on DNA as a means to prove people’s innocence. But now, their work is broader. I think they saw that the prosecution was riddled with problems. The Conviction Integrity Unit in the DA’s office in Fulton County, Georgia, has an open investigation, reexamining the case, and the Innocence Project is engaging with that on Jamil Al-Amin’s behalf.

I’m near the end of working on this book, so I wanted to do a final set of interviews. Having already fought a long battle to interview Imam Jamil in 2021, I assumed that I’d just write the prison and ask if I could come again. But they said No.

So I got back in touch with the Cornell and Arizona State University First Amendment clinics, which had been so helpful earlier, and they wrote up a new legal complaint. Once that complaint was in the system, the prison warden said, “okay, you can do an interview.” So we scheduled that for January 7 and 8 of this year. Back in 2021, I was allowed to bring in a device to record sound, not video. I was given the impression that the same arrangement would apply.

But when I landed in Tucson, I had an email from the prison saying, “You cannot bring in electronic devices.” Next morning, I got to the prison, and they confirmed that I would not be able to record; I had to take written notes instead. We were literally arguing about how many pens I could bring into the interview. [Laughs] They said, “You’re only allowed to bring in one pad and one pen.” I’m like, “What if that pen runs out—can I bring two pens?”

I had. Even then, they told me, “Before you go in, we’ll need to know the serial numbers of the devices you bring in, so we can pass those on to our IT specialists to verify.”

[Sighs] I did sit down with Imam Jamil for two sessions of two hours each. But now, he has a swelling on his face that, I’d say, is protruding about two inches. He’s had no diagnosis.

His health situation was the first thing we talked about. He’s in constant pain. They’re giving him ibuprofen for it. The swelling is starting to wrap over his ear. It’s affecting his hearing, and pushing against his throat so he can’t swallow solids. They’re giving him these Ensure nutritional shakes. That’s basically what he’s living on.

Compared to when I saw him in 2021, it’s a world of difference. He was speaking much more feebly. Mentally, he’s still totally sharp, but physically, he’s very different. They’ve told him that he’s also got blood clots in his legs. He was brought in with a walker. Then we sat down and talked about his life and how he understands it. During our visit, it was hard to hear what he was saying. The only way we could talk was for me to put my head really close to his mouth to hear him. Because his voice is really feeble from the swelling on his head. It’s painful for him just to exist. When I left, we were planning to see each other the next day, on Wednesday.

When I got there Wednesday, they said that they’d taken him to a hospital that morning. So I had to wait, but I was thinking, “Wow, maybe they’re actually getting him some medical treatment.”

Finally, I sat down with him and he told me that they’d taken him to some hospital near the prison, and some bullshit doctor decided to get a needle and puncture the swelling, hoping that it would drain the fluid out. The fluid hadn’t come out, so they tried increasing the thickness of the needle—three different needles. None of them managed to release the fluid. So then they cut the growth and the fluid still didn’t come out. Finally, they bandaged him up and sent him back to the prison. That’s all they did. He’s still had no diagnosis. I just came away from that experience in Arizona so despairing and frustrated. However, over the following weeks, the increasing public pressure on the Federal Bureau of Prisons seems to have had an effect; he’s since been transferred to a medical facility.

I don’t think he has the strength in his hand to easily write. But people can certainly write to him. Apart from that, there’s the actions that the Imam Jamil Action Network are asking people to do.

The Conviction Integrity Unit in Atlanta could find that the prosecution was flawed. Fani Willis, the Fulton County DA, has the power to release him on that basis right now. But you don’t even have to get the district attorney to accept that the prosecution was invalid. It’s really about three things.

One, without having to prove that the original prosecution was flawed, we can confidently conclude that it had massive holes in it. Two, Imam Jamil is 81 years old; he’s been in prison since 2000. Three, he needs proper medical treatment, which can only happen outside custody. Even if you don’t think the weakness of the original conviction by itself gets him out, those three things combined are an overwhelming case to release him.

I mean, the prison is literally killing him, and he’s not been sentenced to death.

NOTE

The Bureau of Prisons now says that Jamil Al-Amin has been transferred to the federal medical center in Butner, North Carolina (FMC Butner).1“FMC Butner,” Federal Bureau of Prisons, accessed February 9, 2025, https://www.bop.gov/locations/institutions/buh/. If you’re interested in writing him, please make sure that he hasn’t been transferred again, by consulting the BOP inmate locator.2“Find an Inmate,” Federal Bureau of Prisons, accessed February 9, 2025, https://www.bop.gov/inmateloc/?os=vb.&ref=app. In addressing the envelope, it’s necessary to add after Imam Jamil’s name his prison number: #99974-555.

You can find a link to the Imam Jamil Action Network here.3“Homepage,” Imam Jamil Action Network, accessed February 9, 2025, https://www.imamjamilactionnetwork.org/.