In the Belly of the Beast

War, Empire, Monsters, and Everyday Life in Hajime Isayama’s Attack on Titan

December 9, 2025

Special thanks to our guest editor, Katie Fustich—writer, translator, and movement lawyer—for her support in shaping this piece.

The late poet Etel Adnan writes that in times of war, we still “walk down the hill,” “look at the Bay,” “wait,” “eat,” “read the bill,” and “pay.” The body continues its habits. And all the while “WAR” is on the front page—in the paper, on the screen, in the background of every ordinary action.

This dissonance—between the monstrosity of imperial warfare and the mundanity of life under it—is central to Attack on Titan, one of the most globally recognized and politically misread anime series of the last two decades. While its surface plot is rich with images of monsters, heroism, and cataclysmic battles, its real target is the machinery of imperialism. At its core, Attack on Titan suggests that the most terrifying monster is not the Titan, but the system that created it.

The series’ manga, which began in 2009, has 140 million copies in current circulation while the TV adaptation, which started in 2013, is lauded as one of the most popular shows of all time, seen as largely responsible for expanding the art form’s global audience.1Maison Tran, “Anime broadens its reach — at conventions, at theaters, and streaming at home,” NPR, January 21, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/01/21/1148406525/anime-hajime-isayama-attack-on-titan. Earlier this year, the series came to a cinematic end with the global theatrical release of a film adaptation of its last two episodes. At its heart, the story is a sprawling political allegory masquerading as dystopian action. It begins on Paradis, an isolated island where humanity lives behind colossal walls, hiding from towering, man-eating giants known as Titans. But what first appears to be a simple tale of survival quickly spirals into something far more complex—a generational saga of empire, memory, and revenge.

The story’s central trio—Eren, Mikasa, and Armin—grow up believing they are the last remnants of humanity, cut off from a mysterious world beyond the sea. Their curiosity about what lies outside the walls becomes an existential drive, especially for Eren, whose mother’s death at the hands of the Titans sparked a deeper, more dangerous ambition: not just to defeat the Titans, but to annihilate them entirely.

As the truth unfolds, rather than inherent monsters, the Titans are revealed to be transformed humans—products of a long, buried history of conquest and retribution. The island’s inhabitants, known as Eldians, descend from the first human to gain the power of the Titans: Ymir, a young girl enslaved by an ancient king who weaponized her abilities to build an empire. When she died, her powers were split into nine distinct Titans and passed down through her bloodline to be used in a centuries-long campaign of domination.

Eventually, the tide turned. A rival nation, Marley, overthrew Eldia, pushing the last of its people to the island of Paradis. To keep them contained—and to bury the truth—the Eldian king Fritz erected massive walls and erased his people’s memories. Meanwhile, Marley repurposed the Titans for its own ends, forcing the remaining Eldians on the mainland into internment zones and recruiting their children to serve as living weapons in an ongoing cycle of imperial warfare.

This is the real horror of Attack on Titan—that is, not the Titans themselves, but the machinery of empire behind them. While elite military police sit safely in Paradis’s innermost walls, civilians are given no choice but to live in a constant state of paranoia. Propaganda ensures that the people of Paradis are kept compliant, and that military greatness is viewed as the highest aspiration. Each regime justifies its brutality as righteous and necessary, shaped by inherited trauma and systems of control.

As one state power falls, another rises. Marley had taken control only to create another empire, and true to postcolonial theorist Edward Said’s characterization, “every empire…tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, that its mission is not to plunder and control but to educate and liberate.”2Edward Said, “Blind Imperial Arrogance,” Los Angeles Times, July 20, 2003, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-jul-20-oe-said20-story.html Attack on Titan strips that illusion bare, showing how state violence, once set in motion, begets more state violence, regenerating itself across generations and borders.

FASCIST COOPTATION

For over a decade, Attack on Titan has soared as one of the most globally successful anime series—and one of the most politically misunderstood.3Tom Spellman, “The fascist subtext of Attack on Titan can’t go overlooked,” Polygon, June 18, 2019, https://www.polygon.com/2019/6/18/18683609/attack-on-titan-fascist-nationalist-isayama-hajime-manga-anime/. Most alarmingly, the series has been claimed by the online far right.4Shaan Amin, “Why Attack on Titan Is the Alt-Right’s Favorite Manga,” New Republic, November 16, 2020, https://newrepublic.com/article/160193/attack-titan-alt-rights-favorite-manga. Members of fascist forums embrace its mythos of racial destiny, citing the story as the “revival of National Socialism” and “one of the most redpilled shows,” all while posting anonymously under a Nazi flag.5Post by “Anonymous,” 4Chan, September 26, 2014, available at https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/36372589/#36372589.

On its surface, Attack on Titan recounts tales of survival, purity, and righteous violence in ways that—absent critical thinking—are attractive to the right. Moreover, creator Hajime Isayama has provided no indication that the story is trying to say anything to the contrary. “Being a writer, I believe it is impolite to instruct your readers the way of how to read your story,” he says.6Gita Jackson, “Everyone Loves Attack on Titan. So Why Does Everyone Hate Attack on Titan,” Vice, April 22, 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/everyone-loves-attack-on-titan-so-why-does-everyone-hate-attack-on-titan/. In the shadow of Isayama’s silence, Attack on Titan has been used by its far right enthusiasts to spread white supremacy.

To Isayama’s credit or not, the actual story of Attack on Titan is far different from the one that has been coopted by fascists online. Rather than a far-right fantasy, the story offers a grim indictment of the racial state, a meditation on the manufactured consent of genocide, and a gruesome and nuanced portrayal of war as everyday capitalist logic rather than its exception. In this way, while it might open with the dystopian plot of a world where towns are pillaged by monstrous Titans, Attack on Titan is not about monsters, but about how empires make monsters. The system is the true monster, producing and reproducing a cycle of continuous violence.

As one state power falls, another rises. Marley had taken control only to create another empire, and true to postcolonial theorist Edward Said’s characterization, “every empire…tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, that its mission is not to plunder and control but to educate and liberate.” Attack on Titan strips that illusion bare, showing how state violence, once set in motion, begets more state violence, regenerating itself across generations and borders.

EMPIRE AS THE REAL MONSTER

The conception of the Titans as physical manifestations of the story’s truer monstrosities draws on a rich lineage of media that utilizes creatures as symbols of cyclical violence and the monstrous logic of capitalist imperialism.

Monsters as metaphors find roots in tokusatsu, or live action Japanese films and TV programs which make heavy use of practical special effects. Often, these films depict kaiju, or “strange beasts” as stand ins for similarly towering, menacing, and, most importantly, human-manufactured evils.

Think skyscraper sized apes, gene-spliced dinosaurs, and sentient machines. There’s also Victor Frankenstein’s creation, cobbled together from corpses and condemned to suffer the consequences of its maker’s ambitions. As literary critic Warren Montag writes in his analysis of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the creature is not simply a being, but “a product…assembled and joined together…by science, technology, and industry.”7Warren Montag, “‘The Workshop of Filthy Creation’: A Marxist Reading of Frankenstein,” in Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: Complete Authoritative Text with Biographical, Historical, and Cultural Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Contemporary Critical Perspectives, ed. Johanna M. Smith (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000), 388. Not born but built, it’s manufactured by the same forces that fuel capitalist modernity.

Each kaiju serves as an embodiment of technological ambition turned violent, and each is also cast as an external threat while emerging from within the very society that claims to fear it. No figure represents kaiju more viscerally than Godzilla. Conceived in the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Godzilla’s form—its wrinkled, scarred skin and cracked, tectonic scales—was designed to evoke the trauma of nuclear war.8Kimmy Yam, “‘Godzilla’ was a metaphor for Hiroshima, and Hollywood whitewashed it,” NBC News, August 7, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/godzilla-was-metaphor-hiroshima-hollywood-whitewashed-it-n1236165. “Technological and industrial progress has produced a monster,” Montag goes on. “An artificial being as destructive as it is powerful.”9Montag, “‘The Filthy Workshop of Creation,’” 388. The monster is not a disruption of the world order but its natural consequence.

Where kaiju narratives often mount a critique of modernization as a destructive byproduct of technological ambition, they do so within a framework that sees violence as erupting in singular, catastrophic moments—like nuclear blasts, failed experiments, runaway machines. From a left perspective, however, modernization under capitalism is less a one-time rupture and more a process that continually reproduces the very conditions for its own crises. The empire expands to secure resources, exploiting communities, fomenting resistance, and then weaponizing that resistance to justify further conquest. This differs sharply from far-right narratives of modernization, which tend to frame violence as an aberration caused by external corruption or degeneracy. Where the right sees modernization as a tool for purification or restoration, the left identifies it as a capitalist, imperialist system whose very logic—endless accumulation, domination, and extraction—guarantees and requires repetition.

The Titans are then all at once the exploited community and the resource itself—both victims and perpetrators, subjects forced to become symbols and used to terrorize, invade, and destroy. As a result, the Titans defy neat categorization. As theorist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen writes in Monster Culture, the monster is a “harbinger of the category crisis” as “a form suspended between forms that threatens to smash distinctions.10Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” in Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, 6. The state, threatened by this ambiguity, reacts with a familiar strategy: it seeks to control, or modernize, what it cannot fully define. Whether Eldia or Marley, every empire builds its power through classification, containment, and dehumanization—strategies that maintain the illusion of order and further modernization even as they reproduce cycles of violence through conquest.

Marley, like Eldia before it, becomes indistinguishable in its imperial logic: it weaponizes the oppressed, fuels endless conquest, and casts its own manufactured monsters as existential threats. This repetition is not incidental nor an aberration, but systemic: each empire inherits the structures of domination that sustained its predecessor, reproducing violence in order to preserve its own survival. In an age defined by militarization and the scramble for dwindling resources, Marley exemplifies the perpetual ambitions of capitalist imperialism, turning to invade Paradis both to capture the power of the Titans and seize the island’s other natural resources (the Titans inclusive). The cycle becomes grotesquely literal when it sends a cadre of child soldiers—Eldians from internment camps—to infiltrate Paradis and reignite war. Among them are the very Titans who, years earlier, shattered the walls of Eren’s childhood, killing its population and catalyzing Eren’s transformation. In this way, the series makes cyclical violence visible, consuming its own children to produce monsters who are at once victims of the system and instruments of its perpetuation.

Eren’s promise of retribution is thus not born in a vacuum. Historical materialism reminds us that individual actions are not merely personal choices but outcomes shaped by one’s conditions. Eren’s family tragedy (the loss of his mother, the collapse of his home) mirrors the larger history of Paradis itself—an island built on tragedy and violence and continuously marked by invasion, confinement, and erasure. What appears as an individual wound is in fact a social wound inherited and reproduced across generations. In short, Eren’s story is not unique. Thrust into the machinery of empire at age ten, like every other child on the island, Eren is a product of the very violence he vowed to destroy. He is the monster society built only to condemn when he turned against it. This is the familiar pattern of modern empire: the state manufactures violence, places blame onto its most visible symbols, and responds with shocked indignance when those symbols retaliate.

Beyond merely depicting this cycle, Attack on Titan interrogates the social logics that sustain it. The series foregrounds how trauma, ideology, and propaganda condition individual behavior. Eren’s material constraints are depicted alongside emotional and cultural ones as well: the mythologies of nationhood, the inheritance of guilt, the romanticization of sacrifice. All of these constraints are deeply social forces that shape a world in which war feels inevitable and monstrosity becomes a mode of survival.

WAR AS THE EVERYDAY LOGIC OF CAPITALISM

The societies that produce the contradictions of empire embodied in the Titans also rely on myths to make their violence inevitable. In Attack on Titan, dehumanization and nationhood operate together: enemies are cast as less than human, while sacrifice for the homeland (that is, destroying the enemy) is celebrated as noble and righteous. These myths fold personal grief into collective destiny, transforming loss into a resource for the state.11Gabriel Winant, “On Mourning and Statehood: A Response to Joshua Leifer,” Dissent, October 13, 2023, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/a-response-to-joshua-leifer/; Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London and New York: Verso, 2009), 37–54. Through this process, violence comes to saturate every corner of social life, not as an interruption (or, again, an aberration) but as the atmosphere in which people grow up, make choices, and imagine their futures. The series lingers on this saturation, staging war as daily reality, a rhythm of blood and fear that no one escapes. In rendering war this way, the show exposes how and why its story could be so easily coopted by fascists; fascism thrives on seducing those under its rule with tales of patriotism, sacrifice, and heroism in the name of nationhood, all while concealing the imperial and capitalist violence inherent to that nation.

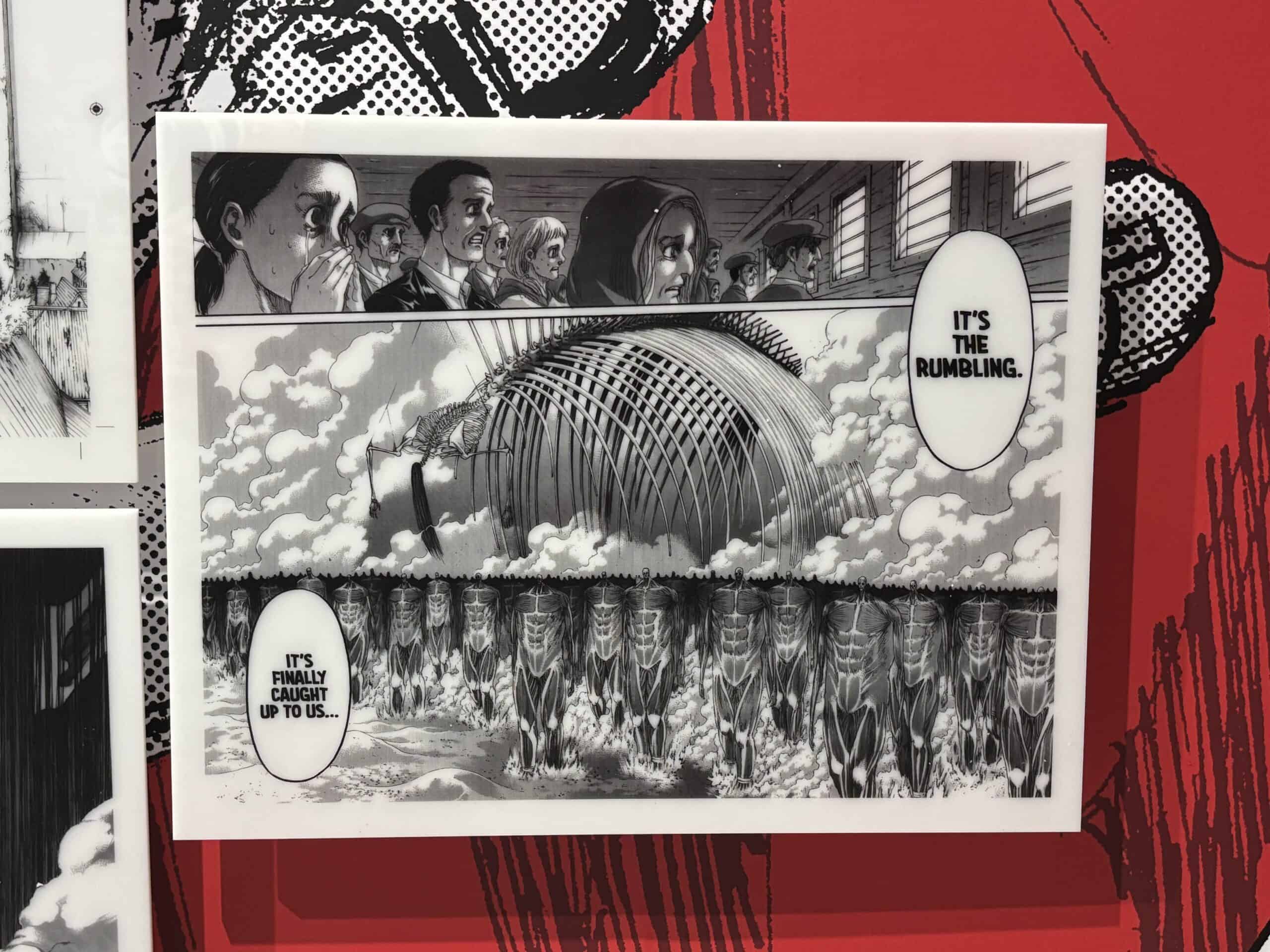

Rather than concealing that violence, Attack on Titan is drenched in it; waves of blood crash in nearly every scene and (save for the kings) no one ever truly rests or returns home. The violence is totalizing. And so, when fascists online claim the show and celebrate its redpill patriotism, they’re glorifying the war, plunder, and genocide required to sustain their nationalism.

Photo Credit: Aaron Boehmer.

This aesthetic choice—to depict war and violence so directly and grotesquely—contrasts sharply with normative political definitions of war, such as those in the US Constitution, which claim war as “a common defence.” Such claims are often masks. What governments call defense is frequently the perpetuation of imperial interests. As the Poor People’s Campaign writes, wars are “fought in the interest of the wealthy, for the gain of the wealthy.”12“A Poor People’s Resistance to War and Militarism,” Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, January 28, 2020, https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/update/a-poor-peoples-resistance-to-war-and-militarism/. bell hooks put it even more bluntly: “I mean let’s face it, war in its essence is another form of capitalism. Wars make people rich—and they make a lot of people poor, and they take a lot of people’s lives away from them.”13Randy Lowens, “How Do You Practice Intersectionalism? An Interview with bell hooks,” Northeastern Anarchist 15 (May 5, 2011): available at https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/randy-lowens-how-do-you-practice-intersectionalism.

hooks’ observation frames war as a monstrous system of extraction: conquer a people’s land, erase their way of life, and disorient them with the perpetual threat of bombardment. Violence is the service; death is the product. Within such a system, the state-sanctioned machinery of war renders individuals into mere numbers on spreadsheets, casualties for greater capital. This monstrous calculus leaves little space for humanity.

Rather than concealing that violence, Attack on Titan is drenched in it; waves of blood crash in nearly every scene and (save for the kings) no one ever truly rests or returns home. The violence is totalizing. And so, when fascists online claim the show and celebrate its redpill patriotism, they’re glorifying the war, plunder, and genocide required to sustain their nationalism.

In the face of this disorientation, the late poet Etel Adnan offers counterforce. Her 2005 poem “To Be In A Time Of War” captures a moment of living—breathing, eating, walking—in parallel with the news of global devastation (namely, the United States’ invasion of Iraq). In a style that mimics stream-of-consciousness journaling, she juxtaposes ordinary acts with extraordinary violence:

To rise early, to hurry down to the driveway, to look for the paper,

take it out from its yellow bag, to read on the front-page WAR,

to notice that WAR takes half a page, to feel a shiver down the spine…

…to suffer from the day’s beauty, to hate to death the authors of such crimes…

…to say yes indeed the day is beautiful, not to know anything,

to go on walking, to take notice of people’s indifference towards each other.

Adnan’s poetry resists the dehumanizing abstraction of war by reasserting the body—its needs, sensations, movements. She offers no neat conclusion, only the persistence of perception, even amid destruction. Her account reminds us that to stay human in a time of war means to notice—to stay tethered to the real, however mundane or fragmented.

Her work thus stands both in contrast and in uneasy dialogue with Attack on Titan. Isayama depicts war’s horror through spectacle: grotesque Titans devouring humans, cities razed in seconds. Adnan counters with attention to the intimate and the personal. Both expose war’s power to dehumanize, but they do so by moving in opposite directions. Isayama scales violence up until it becomes sublime, overwhelming, nearly incomprehensible; Adnan scales violence down until it rests in the twitch of a muscle, the blur of a thought, the sight of a newspaper headline. These strategies create a friction wherein Adnan insists that war can be rejected everyday through minute fragments of grounded perception while Isayama risks reproducing the very abstraction Adnan critiques by rendering violence as monstrous spectacle.

In this tension, Adnan’s words work against the numbing, desensitizing force of continuous war, refusing to let the reader look away from the smallest, most human registers of suffering. Attack on Titan, in contrast, dramatizes how easily violence becomes a shared language, a way of seeing the world through images of destruction so constant they appear natural and normal. Eren, Mikasa, and Armin’s entire existence is predicated on their contributions to a decades-long war. That is the way of life, repeating generation after generation. Time, then, becomes one of the state’s most insidious weapons.14Bahzad Al Akras, “War on Gaza: Israel’s Deadliest Weapon is Time,” Middle East Eye, February 13, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/war-gaza-israel-deadliest-weapon-time.

If Adnan’s poetry warns of war’s reduction to spectacle, Isayama shows what it looks like when spectacle itself becomes the texture of everyday life. Read together, the works mark the boundaries of two aesthetic modes: one that preserves humanness against abstraction, and another that demonstrates how abstraction and violent spectacle has come to saturate everyday life under empire.

These realities are exemplified in Attack on Titan’s worldbuilding, which uses aesthetic representation to make the logics of empire visible. Using nineteenth and twentieth century European architecture, clothing, and allusions, Isayama casts Eldia as a colonial empire akin to Spain or Britain. In a similar vein, Marley’s imperial expansion evokes Nazi Germany as well as settler-colonial states like the United States and Israel. Both empires rely on expansion and the racialization, exploitation, and demonization of “others” to maintain their power. As each rose to power, what Eldia did to Marley, Marley did right back. First, the state of Eldia exploited the “Subjects of Ymir” as products—tools for war—and then Marley did the same. The cycle of empire-building, expansion, collapse, and reconstruction mimics historical successions of colonial domination.

In this way, the show’s mythos, historically rooted, performs a kind of meaning-making, reiterating to viewers how expansion, racialization, and subjugation are bound together in the construction of nationhood. This fantasy world reflects and refracts our own, reminding us that empire always requires myth, constructed meaning, and a monstrous “other” to sustain itself.

And if Titans are that monstrous “other” transformed by the state into weapons, then the spectacle of monstrous violence implicates everyone who consents to or benefits from that system. To cheer at the slaughter of the monsters is also, belatedly, to cheer at the destruction of the human life required to make those monsters, which were created by the very empires claiming to protect humanity—that is, its victims. To be complicit in a world that manufactures monsters is to accept dehumanization as normal—whether by looking away, buying into nationalist myths, or reducing lives to tools of war.

The question “who is the real monster?” refuses a simple answer. It is the Titan in some cases. It’s also Eren at one point. But most consistently, it’s the imperial apparatus that requires continual sacrifice to reproduce itself. In forcing this confrontation, Attack on Titan unsettles viewers’ comfort with spectacle: it asks us to consider whether our own appetite for watching such violence risks mirroring the same logic of dehumanization. Further, it requires the viewer to sit with complicity, refusing to feed you a clean moral answer.

Photo Credit: Aaron Boehmer.

No figure embodies these questions more than Eren. Once a victim of imperial violence, he becomes an agent of mass destruction. Seduced by the goal of annihilation, he comes to believe that flattening the world is the only path to freedom. In doing so, he enacts the very horror he once sought to escape. His arc is not heroic. It subverts that tradition: the avenger becomes the executioner. Even after Mikasa slays Eren, the world continues to burn and the cycles of war, imperial violence, and capitalistic extraction continue. At the end of the series, we see flashes of future civilizations that rise after the fall of Paradis and Marley. While apparently more advanced and modernized, they are still at war—still submerged in perpetual violence.

The question “who is the real monster?” refuses a simple answer. It is the Titan in some cases. It’s also Eren at one point. But most consistently, it’s the imperial apparatus that requires continual sacrifice to reproduce itself. In forcing this confrontation, Attack on Titan unsettles viewers’ comfort with spectacle: it asks us to consider whether our own appetite for watching such violence risks mirroring the same logic of dehumanization. Further, it requires the viewer to sit with complicity, refusing to feed you a clean moral answer.

Isayama’s choice to end the series without redemption is deliberate. “It’s just not plausible in the world we’re living in right now,” he told The New York Times in 2023.15Rafael Motamayor, “‘Attack on Titan’ Ends How Its Creator Always Envisioned,” New York Times, November 5, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/05/arts/television/attack-on-titan.html. A happy ending would be dishonest. The absence of closure also opens space for reflection.

If there’s no neat escape from the cycle, then the small acts—of rising early, of writing, of walking—take on new meaning. This is where Adnan returns to remind us that holding close an attentiveness to life, even when fractured, is paramount.

At one point in her poem, Adnan writes that to be in a time of war is “to say yes indeed the day is beautiful, not to know anything,” and then “to go on walking.” By the poem’s end, she writes that it also means “to look at the narrow and long road which leads the world to the slaughter-house.” And maybe then we can pave a different path toward a different horizon.