Reactionary Decarbonization

On Carbon Capture and Techno-Utopianism

January 21, 2025

To walk into the Americans Energy Summit, as I did last fall in New Orleans, is to glimpse an arresting new reality: fossil fuel companies claiming to be leaders of the energy transition. Instead of denialist talking points, gas executives stress their commitments to reducing Scope Two emissions, tout their new “low carbon solutions” departments, and talk of vast new business opportunities to build carbon dioxide and hydrogen infrastructure. Now tacitly or explicitly accepting the need to reduce emissions, they insist that renewables will not get us there: the world still needs molecules—whether hydrogen, ammonia or methanol—that can be produced in low-carbon (“blue”) form with the help of carbon capture and storage (CCS). No longer is the problem fossil fuels, but emissions, which can be managed with the existing technological know-how of the fossil fuel industry. Rather than face marginalization in a renewable energy economy, fossil fuel companies now project themselves as leaders in “carbon management.”1For a flavor of these commitments, see both Exxon Mobil and Shell’s websites. “Carbon capture and storage: Providing industry solutions needed to help reduce emissions during the energy transmission,” Exxon Mobil, accessed December 28, 2024, https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/what-we-do/delivering-industrial-solutions/carbon-capture-and-storage; “Shell accelerates drive for net-zero emissions with customer-first strategy,” Shell, February 11, 2021, https://www.shell.com/news-and-insights/newsroom/news-and-media-releases/2021/shell-accelerates-drive-for-net-zero-emissions-with-customer-first-strategy.html.

They are supported in this endeavor by an array of liberal environmental organizations. This includes several of the “big greens”—including the National Wildlife Federation, the Nature Conservancy, the Clean Air Task Force, and the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions—who, with energy sector unions, have joined fossil fuel companies as part of the Carbon Capture Coalition. Taking their justification from IPCC emission reduction scenarios, which increasingly rely on carbon capture and negative emissions technologies, they view CCS as “critical to achieving net zero emissions.”2“About the Carbon Capture Coalition,” Carbon Capture Coalition, accessed December 29, 2024, https://carboncapturecoalition.org/about-us/. Many such advocates add the vague caveat that it must be done “responsibly,” with “meaningful engagement and consultation with local communities,” community benefits agreements, and so on.

While troubled by the connection between CCS and fossil fuel companies, several scholars farther left have argued for the possible uses of this technology were it to be inserted into radically different social relations. Most of these scholars focus specifically on Direct Air Capture (DAC), a subspecies of CCS that focuses on capturing carbon dioxide from the air rather than power plants and industrial sources (it is also often grouped under the category of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)). The progressive argument for DAC arises from the problem of overshoot: because of decades of denial and delay, even a rapid cessation of fossil fuel combustion would leave excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that must be drawn down. This makes even the most trenchant critics of the fossil fuel industry reluctant to dismiss DAC tout court. For instance, Malm and Carton offer a thoughtful and detailed critique of DAC on multiple grounds—including its energy and infrastructural requirements, imbrication with fossil capital, and the license it offers to continue combusting (and thus “its eminent compatibility with the prevailing order).”3Andreas Malm and Wim Carton, “Seize the Means of Carbon Removal: The Political Economy of Direct Air Capture,” Historical Materialism 29, no. 1 (2021): 3, https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-29012021. They argue that “any DAC strategy that does not begin with…dismantling fossil capital as fast as humanly possible, is a wasted effort.”4Malm and Carton, “Seize the Means of Carbon Removal,” 36. They conclude, however, that DAC may soon become a fait accompli. And since its application by fossil fuel companies under capitalist social relations would produce all kinds of perverse results, they suggest that the left focus on “socializing the means of removal,” which could allow the technology to repair climate damage.5Malm and Carton, “Seize the Means of Carbon Removal,” 3. They recognize, however, that no such alternative trajectory “is currently on the cards.”6Malm and Carton, “Seize the Means of Carbon Removal,” 36.

Christian Parenti advances a more full-throated “left defense of carbon dioxide removal,” in which he chastises environmentalists for their “technophobia and nature fetish.”7Christian Parenti, “A left defense of carbon dioxide removal: The state must be forced to deploy civilization-saving technology,” in Has it Come to This? The Promises and Perils of Geoengineering on the Brink, ed. J.P. Sapinsky, Holly Jean Buck and Andreas Malm (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2021), 131. Parenti argues that the problem is not the technology, but the social relations in which it is embedded. Carbon removal should be decommodified and treated as a public utility. He concludes, however, that “a state-led crash program of CDR would only be meaningful within the context of a broader program of radical mitigation involving euthanizing the fossil fuel industry….”8Parenti, “A left defense of carbon dioxide removal,” 139.

Holly Jean Buck has been the climate left’s most ardent advocate of CCS—not just DAC—and has fewer reservations than Malm and Carton. Weaving between social science and science fiction registers, Buck’s book After Geoengineering offers a redemptive (albeit melancholic) techno-utopian vision in which geoengineering solutions are democratically managed, redistributive, and reparative.9Holly Jean Buck, After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair and Restoration (London: Verso, 2019). Buck argues that CCS could be these things if it were used to capture emissions from industry or gas-fired power plants, rather than being used to prolong coal or drill more oil (through a process, known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), in which carbon dioxide is injected into depleted wells to extract more oil).10Buck, After Geoengineering, 126. In other writing, Buck chastises environmental justice groups for wasting their time on the “distraction” of opposing CCS as a “false solution,” rather than focusing on what they are for—including, potentially, more democratic or egalitarian deployments of the same technology.11Holly Jean Buck, “The Carbon Capture Distraction,” Dissent, Spring 2023, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-carbon-capture-distraction/. Buck questions whether the critiques of CCS by environmental justice groups are accurate, repeats industry claims about the technology’s efficacy and safety, and claims that climate advocates who dismiss the feasibility of CCS are unwittingly supporting the excuses of fossil fuel companies who, she argues, do not want to pay for it. In an oblique critique of the environmental justice movement, Buck concludes that “the cost of being absorbed by the CCS distraction is not one that the movement can afford.”12Buck “The Carbon Capture Distraction.”

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is the cutting edge of what I suggest we call reactionary decarbonization. It is reactionary because it represents a defensive recalibration of the fossil energy regime to ward off the radical challenge to its existence posed by the climate movement. It is also reactionary because in shoring up the regional hegemony of the oil and gas industry, CCS not only reproduces but expands its ecologically destructive and unequal status quo—especially in the racial distribution of toxic risk.

What follows should be seen as a similarly oblique critique of such left CCS visions. I am not interested in making normative arguments for or against a technology in an imaginary set of social relations. Rather, I aim to provide a deeper look into how CCS is actually being rolled out today in the United States, and to demonstrate how terribly far this is from anything the climate left should even consider getting behind. I will suggest that the vast chasm that exists between these left techno-optimist visions and the deeply dystopian reality raises important questions of both theory and political strategy. In brief, this huge disjuncture puts more onus on the techno-optimists to show that their visions are not simply abstract utopias, as opposed to critical theories grounded in actual but unrealized possibilities.13As Marcuse develops this Marxian distinction, critical theory must abstract from the “actual organization” of society to identify “arrested and denied possibilities,” but this abstraction is “opposed to all metaphysics by virtue of the rigorously historical character of the transcendence. The ‘possibilities’ must be within the reach of the respective society; they must be definable goals of practice. By the same token, the abstraction from the established institutions must be expressive of an actual tendency—that is, their transformation must be the real need of the underlying population.” Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man (Boston: Beacon Press, 1964), xi. See also Karl Marx, “Manifesto of the Communist Party.” Karl Marx, “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” in The Marx Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: Norton, 1978), 497–99; Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program (Oakland: PM Spectre Classics, 2023). It raises the political question of whether the left should add any intellectual or political support to a project that is being driven now, and will almost certainly continue to be for many years to come, by the fossil fuel industry with all manner of socially regressive and ecologically destructive results.

For the reality is that the train has left the station: CCS is no longer science fiction or something that the fossil fuel industry is avoiding. Since the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 nearly doubled the tax breaks for each ton of carbon dioxide stored—from $45 to $85 per cubic ton—over a hundred CCS projects have been proposed across the country.14Mathilde Fajardy and Carl Greenfield, “It is time for CCUS to deliver,” iea.org, March 15, 2024, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/it-is-time-for-ccus-to-deliver. These are almost exclusively being managed by the fossil fuel industry, of which CCS is a growing and lucrative sector. Most entail capturing carbon dioxide from power plants and industrial sources—especially petrochemical and ethanol plants—and transporting them through new pipelines for permanent geological storage (not enhanced oil recovery) in what are called Class VI Injection Wells. Only a small minority, including four regional hubs funded partially by the Department of Energy (DOE), involve DAC—and, as I will point out, these projects resemble CCS projects in most respects.

It is no longer possible to claim that capitalists are uninterested; quite the contrary, we are in the midst of a massive speculative CCS boom. I spent the last year studying it wash over Louisiana, which, along with Texas, is at the boom’s epicenter. I attended meetings in communities slated for CCS infrastructure—whether carbon dioxide injection wells, carbon dioxide pipelines or new petrochemical plants that would produce “clean fuels” like blue ammonia and hydrogen using carbon capture. I accompanied residents as they organized their communities, questioned company executives in public hearings, and traveled to Baton Rouge to confront the oil, gas and chemical lobbies, which are thoroughly arrayed behind CCS along with the state’s Republican and Democratic parties. I interviewed over 150 people in some way entangled in this new CCS buildout, whether in industry, government, academia, nonprofits or as affected citizens. What I conclude from this research is the following.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is the cutting edge of what I suggest we call reactionary decarbonization. It is reactionary because it represents a defensive recalibration of the fossil energy regime to ward off the radical challenge to its existence posed by the climate movement. It is also reactionary because in shoring up the regional hegemony of the oil and gas industry, CCS not only reproduces but expands its ecologically destructive and unequal status quo—especially in the racial distribution of toxic risk. Whether CCS is truly decarbonization is a more difficult question. It seeks to remove carbon dioxide only at the very last stage of the fossil economy (combustion), leaving the remainder of its metabolic cycle intact. It does not represent energy transition, as it is precisely the preservation rather than liquidation of fossil fuels. With that in mind, the concept of reactionary decarbonization points to the cynical way in which CCS allows fossil fuels to inhabit and redirect the decarbonization imperative down a pathway that is neither just nor a transition.

In the United States, this reactionary decarbonization road has been paved by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), widely heralded by liberal climate advocates as America’s “historic” climate legislation.15Robinson Myer, “Biden’s Climate Law Is Ending 40 Years of Hands-Off Government,” Atlantic, August 18, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/08/climate-law-manchin-industrial-policy/671183/. In what follows I explain how the IRA, which relies on tax breaks for private capital to drive the energy transition, has unleashed a speculative boom for geological pore space by the oil and gas industry and incentivized a major new buildout of petrochemical plants and pipeline infrastructure. On the one hand, this boom is intensifying ecological devastation and imposing public health risks across society, bringing it to rural white residents who have historically been major beneficiaries of the oil and gas industry. At the same time, the CCS boom—and particularly the “blue” petrochemical expansion it authorizes—interacts with the racialized class structure of Louisiana to expand the racial inequality in toxic harm rooted in the legacy of slavery and the failures of Reconstruction.

The IRA and the CCS Boom

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) refers to the process of capturing carbon dioxide from power plants or industrial sources—or in the case of DAC, from the air—and then transporting it to sites where it can be geologically sequestered.16I leave aside utilization—using the captured carbon dioxide to produce useful commodities—because it is not a major component of the current CCS boom. In short, it means burying carbon dioxide underground—often over a mile deep into varied geological formations—instead of ceasing the combustion of fossil fuels altogether. Among potential climate solutions, the appeal to the fossil fuel industry is obvious. Until recently, the problem was that CCS was both technologically untested at scale and economically unviable. The latter changed almost overnight with the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which almost doubled the tax-credit (called 45Q) for sequestering carbon from $45 per cubic ton of carbon dioxide to $85 (the tax break for DAC is even steeper, at $180). This immediately made many carbon capture projects economically viable, unleashing a scramble for geological pore space suitable for carbon dioxide sequestration.

Distinct from the mineral rights at stake in oil and gas booms, carbon capture requires rights to “pore space,” which refers to the tiny voids between particles of sand and sediment. For permanent carbon dioxide sequestration, the ideal geology is one with a high volume of pore space trapped beneath impermeable cap-rock. This is also the geology that makes for oil and gas wells, which is why many CCS projects are proposed for depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs.

Once again, Louisiana has become a test case—a “guinea pig,” as many residents put it—for new developments in the energy economy. What does its early and headlong rush into carbon capture tell us about the kind of society we might be living in if we continue down this pathway?…The short answer is: a society with more destructive and dangerous energy infrastructure, including pipelines, injection wells, and petrochemical plants.

Louisiana, with its existing oil and gas infrastructure and apparently ideal geology, has emerged as the United States’ CCS hotspot. Twenty-three Class VI injection wells are awaiting permits, the responsibility for which now rests with the Louisiana state government after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—against strenuous objections from environmental justice organizations—granted the state regulatory “primacy” late last year. At least two dozen more projects are proposed. Fourteen Class V injection wells, which are tests to demonstrate the viability of permanent sequestration, have already been approved, and a handful of them already drilled (these look indistinguishable from an oil well). Some are proceeding on large tracts of private land, typically owned by forestry, land management, or oil and gas companies themselves. Others are proceeding on public lands and “water bottoms,” mainly wetlands and lakes. Leases for the latter show that the injection fee charged by the state mineral board increased by a factor of five over two years.17Based on an analysis of CCS leases. See “Office of Mineral Resources: Special Notices and Announcements,” State of Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources, accessed December 28, 2024, https://www.dnr.louisiana.gov/page/special-notices-and-announcements. The only precedent for such a gold rush in recent memory, one government official told me, was the Haynesville Shale play a decade earlier.

It should be emphasized that almost every single company involved in CCS injection wells is an oil and gas company, or subsidiary of one. They include the likes of ExxonMobil, Shell, TotalEnergies, Venture Global, and Occidental Petroleum. Early movers included the industrial gas company Air Products and OxyChem, who had leases signed before the ink dried on the IRA. While the initial boom involves some smaller industry players trying to be the first to get an injection hub in place and likely cash out, we can expect concentration. ExxonMobil is positioning itself to capture a major share of the carbon management market. In 2023, the company paid $4.9 billion for Denbury, which operates the largest carbon dioxide pipeline infrastructure in the country, largely used for EOR.18“ExxonMobil completes acquisition of Denbury,” ExxonMobil, November 2, 2023, https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/news/news-releases/2023/1102_exxonmobil-completes-acquisition-of-denbury. Exxon CEO Darren Woods subsequently announced that they would be investing $20 billion in carbon capture, and industry insiders expect it to rapidly build economies of scale in transport and sequestration.19Susan Lahey, “Exxon Ramps Low Emissions Opportunities Spend to $20 Billion,” ESG Today, December 6, 2023, https://www.esgtoday.com/exxon-ramps-low-emissions-opportunities-spend-to-20-billion/; “ExxonMobil Corporate Plan more than doubles earnings potential from 2019 to 2027,” ExxonMobil, December 6, 2023, https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/news/news-releases/2023/1206_exxonmobil-corporate-plan.

In conjunction with the injection wells, a new wave of petrochemical plants has been proposed to produce fuels that would be labeled “clean” because they intend to capture the byproduct carbon dioxide—though not necessarily other pollutants—and sequester it. While some projects involve retrofitting or expanding existing chemical plants, the Louisiana buildout also includes eight proposed “blue ammonia” and “blue hydrogen” plants—the blue being a marketing term for products that are “low-carbon” because of their use of CCS. In addition to capturing IRA tax breaks, these companies are eyeing emerging markets for ammonia as a “clean fuel” in shipping and power, in addition to a growing demand for lower-carbon products in the traditional fertilizer market. Ammonia is roughly 18 percent hydrogen by weight and is more efficient to transport than pure hydrogen, making it a likely candidate for long-distance transport should the hydrogen economy take off.

Connecting the injection wells and “clean fuels” plants would be a whole new network of carbon dioxide pipelines, with hundreds of miles proposed in Louisiana so far. Some estimates see the total coming to over two thousand miles by 2040–50.20Kert Davies, “Princeton Maps Reveal US Plans for Massive CO2 Pipeline Buildout,” DeSmog, May 31, 2023, https://www.desmog.com/2023/05/31/princeton-maps-ccs-us-plans-co2-pipeline-buildout/. This would represent a whole new layer of risky energy infrastructure in a state that is already crisscrossed by fifty thousand miles of oil and gas pipelines.21“Pipeline Operations Program,” State of Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources, accessed December 28, 2024, https://www.dnr.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/page/150.

There is much churning, with projects emerging and disappearing by the month. Several Louisiana projects have already withdrawn permits, presumably for technical and economic reasons. Some amount to little more than press releases, or a shell LLC thrown together by Houston consultants who managed to get financial backing from a “green” investment fund. The CCS buildout thus has all the makings of a speculative boom: a lot of spaghetti being thrown against the wall, only some of which will stick.

What drives the boom is the value that the IRA gives to carbon dioxide emissions. As a CCS project consultant put it to me, “the emitters are holding the gold”—in other words the carbon dioxide emissions that qualify for the $85 per cubic ton tax credit if captured. To put that in perspective, Air Products claims it will inject five million metric tons of carbon dioxide into its wells proposed for Lake Maurepas (more on which shortly), River Parish Sequestration plans to inject fourteen million a year and Denbury’s Pegasus Sequestration hub thirty miles southeast of New Orleans plans for ten to twenty million metric tons.22Oil & Gas Watch, Fact Sheet: Carbon Capture and Storage in Louisiana (Washington DC: Oil & Gas Watch, 2023), https://environmentalintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/OGW_LACCSProjects_FactSheet_Final.pdf. While these projections may well be inflated, the tax windfall for fossil fuel companies will be in the hundreds of millions of dollars per year per project. The main cost for the emitters is the carbon capture equipment, which varies significantly based on the kind of industrial activity. From the 45Q tax credit, the emitter must be able to cover the cost of transporting and storing the carbon dioxide, which is in many cases contracted out to a third party.

In Louisiana, then, the carbon capture boom has become tangible. Parish governments have been put on notice, sometimes informing local populations who have mobilized against it. Because of this upswell of opposition, carbon capture has been debated in Baton Rouge, a legislative task force has been formed to study its local impacts, and multiple bills to regulate the industry have been introduced (and usually defeated). Once again, Louisiana has become a test case—a “guinea pig,” as many residents put it—for new developments in the energy economy. What does its early and headlong rush into carbon capture tell us about the kind of society we might be living in if we continue down this pathway?

The Carbon Management Society

The short answer is: a society with more destructive and dangerous energy infrastructure, including pipelines, injection wells, and petrochemical plants. This infrastructure will bring more risk to more people living in proximity to plants that emit and pipelines that can rupture. Its construction will involve more dredging, more degradation of wetlands and lakes, and cutting of forests. It will also not improve, and in many contexts will worsen, pollution because CCS does not necessarily capture “copollutants.” All of this will be done with massive taxpayer subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, which can now claim credit for being part of the solution.

A major reason why “Cancer Alley” is known as a hotspot for environmental racism is structural: the petrochemical industry succeeded directly upon the land tenure and social structure of plantation slavery.…The legacy of slavery is thus built into the geography, land tenure, division of labor, and political management of Louisiana’s petrochemical economy.

Although industry claims all this is perfectly safe and well within their existing expertise—an assessment that Buck appears to accept—it is worth emphasizing that little of this is proven on scale and there is great uncertainty surrounding almost every aspect of this process. While the clean fuels plants claim they will capture northward of 90 percent of their carbon dioxide emissions, advocates of CCS can point to virtually no examples of such rates being achieved.23Nicholas Seifeld, “St. Charles Parish. The Future Home of a Cutting-Edge $4.6 Billion ‘Blue’ Ammonia Plant,” ChemAnalyst, April 20, 2023, https://www.chemanalyst.com/NewsAndDeals/NewsDetails/st-charles-parish-the-future-home-of-a-cutting-edge-46-billion-blue-ammonia-plant-17104; Mark Jacobsen, No Miracles Needed: How Today’s Technology Can Save Our Climate and Clean Our Air (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). Carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant and carbon dioxide pipelines have burst. This happened most notably in Satartia, Mississippi in 2020, when a Denbury carbon dioxide pipeline used for EOR ruptured and sent forty-five people to the hospital in respiratory distress.24Julia Simon, “The U.S. is expanding CO2 pipelines. One poisoned town wants you to know its story,” NPR, September 25, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/05/21/1172679786/carbon-capture-carbon-dioxide-pipeline. Emergency responders found people unconscious and foaming at the mouth, and many were left with lasting health problems. Another leak occurred this past spring from a Denbury pipeline in Sulfur, Louisiana, prompting a shelter-in-place order.25Nina Lakhani, “‘Wake-up call’: pipeline leak exposes carbon capture safety gaps, advocates say,” Guardian, April 19, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/apr/19/exxon-pipeline-leak-carbon-capture-safety-gaps. While CCS advocates claim that carbon dioxide pipelines have an excellent safety record, what is on order here is a pipeline network of far greater magnitude and proximity to populations than the small one that currently exists for EOR. Nationally, the DOE envisions an additional seventy thousand miles of carbon dioxide pipeline, on top of the five thousand miles currently in existence and largely used for EOR.26Jack Suter et al., Carbon Capture, Transport, & Storage. A Supply Chain Deep Dive Assessment (Washington DC: U.S. Department of Energy, 2022), https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/Carbon%20Capture%20Supply%20Chain%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf. This means a massive expansion in the number of people living adjacent to potentially asphyxiating—as well as ecologically destructive—energy infrastructure.

There are also many questions surrounding underground injection, including the mobility of carbon dioxide plumes, their chances of migration through geological features or old oil wells—Louisiana has 148,000 plugged wells, 28,000 unplugged wells and another 4000 orphaned wells—and the threat they may consequently pose to aquifers and human health.27“Addressing Methane Emissions in Louisiana: How Many Jobs Will it Take?” True Transition, accessed December 28, 2024, https://www.truetransition.org/m. As I write, the United States’ first carbon dioxide injection well, operated by ADM in Decatur, Illinois, reported an underground fluid leak. The EPA has determined ADM injected into an unauthorized zone and failed to follow monitoring and emergency response procedures.28Carlos Anchonde, “First US CO2 injection well violates permit – EPA,” E&E News, September 13, 2024, https://www.eenews.net/articles/first-us-co2-injection-well-violates-permit-epa/. Carbon dioxide injection companies can now insure against carbon dioxide loss and transfer liability for injection wells to the state after fifty years, which means that the risk of infrastructure failure largely falls on the public. Liability for those wells will transfer to the state after fifty years. Importantly, industry has been deliberately mum on the trace chemicals that would be mixed up in the captured carbon dioxide . As with pipelines, carbon dioxide leakage is a public health concern that has been brushed aside by industry. A proposed Louisiana bill that would have created a two-mile setback between injection wells and schools, hospitals and residences was neutered, bringing it to a meager five hundred feet.

I am not an engineer, and I do not think the strongest critique of CCS is that “it doesn’t work.” But it would be absurd to claim that all of this is settled science. CCS involves many risks, as well as direct environmental harms. And it is indisputable that citizens have no reason to trust the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries, nor Louisiana regulators.

It is also far from clear that foisting these risks onto society will result in substantial emissions reductions. First, CCS prolongs the extraction, transport, and use of fossil fuels with all the attendant emissions and methane leaks this involves. Second, carbon capture equipment requires significant additional power, which must either come from fossil fuels or from renewables that would otherwise displace fossil fuels.29Jacobsen, No Miracles Needed, 152; Emily Grubert and Shuchi Talati, “The Distortionary Effects of Unconstrained For-profit Carbon Dioxide Removal and the Need for Early Governance Intervention,” Carbon Management 15, no. 1 (2023): 10, https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2023.2292111. Third, we have seen that the CCS subsidy in the IRA has perversely encouraged a buildout of new plants, representing new emissions that would not exist if it were not for the subsidies for capturing them. Even if those plants captured upwards of 90 percent of their emissions—a claim so far unproven—they would still represent net positive emissions.30Jacobsen, No Miracles Needed, 152; Grubert and Talati, “The Distortionary Effects of Unconstrained For-profit Carbon Dioxide Removal,” 10. Finally, critics point out that these massive subsidies of CCS—which will certainly reach the hundreds of billions—are an expensive diversion from investments in renewables and industrial electrification.31Emily Grubert and Frances Sawyer, “The US Power Sector Carbon Capture and Storage Under the Inflation Reduction Act Could be Costly with Limited or Negative Abatement Potential,” Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability 3, no. 1 (2023): https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/acbed9; Adam Orford, “Overselling BIL and IRA,” Ecology Law Quarterly 51 (2024): http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4617527; Devin A. Lowell, “Uncaptured: The CCUS Boom, Environmental Justice, and Cancer Alley,” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 74, no. 1 (2024): 88–116, https://journals.library.wustl.edu/lawpolicy/article/8924/galley/25695/view/. These criticisms of CCS on its own terms deserve careful consideration.

What I would like to foreground, however, is the social and ecological costs of CCS on the ground. This is most clearly appreciated by example. Take the most advanced and contentious CCS project in Louisiana to date: Air Products’ proposed carbon dioxide injection wells in the middle of Lake Maurepas. Part of a proposed $4.5 billion Louisiana Clean Energy Complex which also involves a new pipeline and blue ammonia plant, the carbon dioxide injection wells would involve building approximately twenty platforms connected by pipelines in the middle of the lake. Lake Maurepas, which flows into the much larger Lake Pontchartrain north of New Orleans, is one of few water bodies in south Louisiana not already crisscrossed by pipelines or dotted with oil and gas platforms. It is surrounded by freshwater cypress and tupelo swamp, much of it protected by a 112,000-acre Wildlife Management Area. The wells would inject an estimated five million cubic tons of carbon dioxide per year about a mile under the lakebed. To get the carbon dioxide there requires cutting a thirty-five-mile pipeline through a protected wildlife area, dredging the lake bottom, and building sixteen to twenty platforms in the middle of the lake.32Julie Dermansky, “The Battle to Stop Air Products’ Carbon Capture Project at Lake Maurepas Grows,” DeSmog, February 17, 2023, https://www.desmog.com/2023/02/17/air-products-lake-maurepas-louisiana-ccs-blue-hydrogen/. The company has already undertaken seismic testing, setting off sixteen thousand 2.5 kg charges in the lake, and drilled a test well.33Rick Mullin, “The battle for Lake Maurepas,” Chemical & Engineering News, April 2, 2023, https://cen.acs.org/environment/battle-Lake-Maurepas/101/i11.

Residents from the surrounding parishes, who are largely white and blue collar, oppose the threat it poses to the lake, where they grew up fishing, hunting, boating and taking their families to “camp” along its banks. They are worried that it will degrade the lake, threaten drinking water, and potentially asphyxiate them in their sleep if the carbon dioxide were to leak. Commercial crabbers fear that damage to the lake bottom will destroy their livelihoods.

Although private property values may in some cases be endangered, these residents are primarily defending a commons against privatization (though they don’t use that term). Much in the vein of E. P. Thompson’s analysis of enclosure and common right in Whigs and Hunters, they question that a public resource should be effectively privatized and point out that, while their uses of the lake (fishing and hunting) are deeply regulated, the state is giving a private company the green light to cut down swamps and rip up the lake bottom.34E.P. Thompson, Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act (New York: Pantheon, 1975). They also question how the project could even potentially be good for the climate, given that the carbon dioxide to be captured would come from an entirely new blue ammonia and hydrogen plant that would not have otherwise existed. They have organized themselves into a preservation society, pushed all their local representatives into alignment on the issue and fought—thus far unsuccessfully—to impose a moratorium on CCS in the lake and in the state. The movement involves many retired petrochemical plant workers who find themselves arrayed against the industry for the first time. Though politically conservative and not otherwise inclined to climate action, most of their critiques of the project are persuasive.

Most residents I have interviewed feel overburdened by the existing pollution…. The idea of putting a fossil gas-fed ammonia plant on two hundred acres of wetland next to an already overburdened Black community in the name of climate change seems patently absurd to them. They rightly view the blue ammonia plant as a straightforward extension of the petrochemical industry that has been poisoning them for decades.

The state’s other carbon dioxide injection wells are also largely going into rural areas where there are large tracts of forests or wetland to inject under. For some projects, the state is effectively using eminent domain to expropriate pore space rights from property owners.35While Republican legislators recently passed a law that would replace eminent domain with a unitization scheme similar to that used for managing oil and gas reservoirs—in which revenue is distributed across mineral rights owners using a formula–this is effectively eminent domain in another guise as the sequestering company would only need to receive the approval of owners of 70 percent of the pore space (not 70 percent of owners). This allows a company to develop a project with one big lease—of public or private land—and effectively condemn the rights of smaller surrounding landowners. As I write, parish-level opposition to CCS injection wells is spreading like wildlife across the state.

While advocates of DAC tend not to view it in the same bucket as CCS, it is important to recognize that from the public’s perspective the two are largely indistinguishable. While Louisiana’s one DAC plant—Project Cypress, which has received $600 million from the DOE—will suck carbon from the air rather than petrochemical plant emissions, it will use the same types of pipelines and injection wells. Local citizens of the Vernon and Rapides Parishes have begun mobilizing against the project, worried about carbon dioxide and other fluids being pumped under their communities.36Many of the companies involved in DAC are not fossil fuel companies—though the South Texas DAC Hub is being developed by a wholly owned subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum. Louisiana’s Project Cypress is being developed in part by Climeworks, a Swiss company that is lionized in the “DAC space.”

Then there is the other end of the carbon capture boom: the plants that would produce fuels deemed “clean” because their carbon dioxide would ultimately be sequestered in the injection wells. These are almost exclusively following the geography of the state’s current petrochemical industry into Black communities.

CCS and Structural Racism

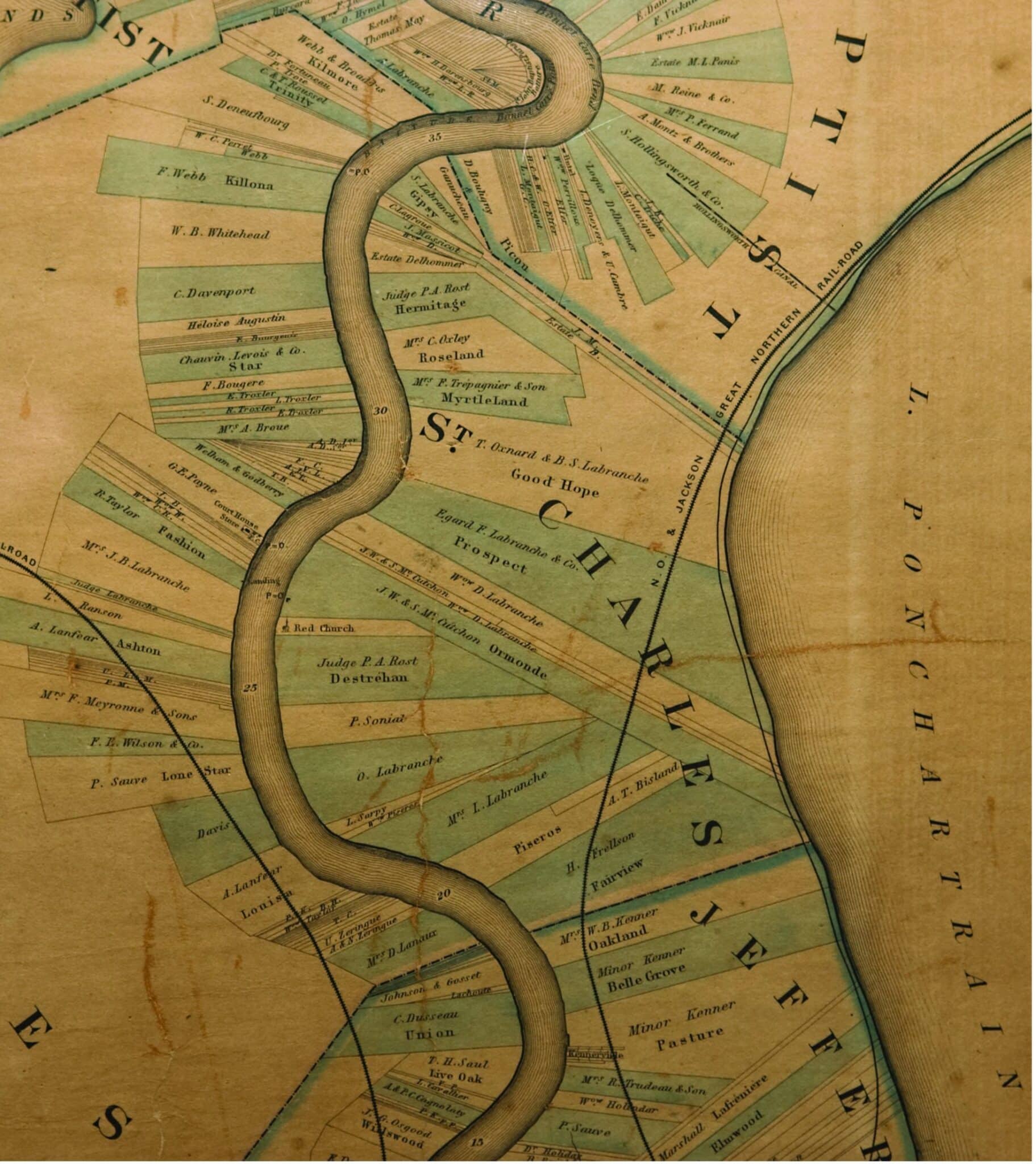

A major reason why “Cancer Alley” is known as a hotspot for environmental racism is structural: the petrochemical industry succeeded directly upon the land tenure and social structure of plantation slavery. Starting in the early eighteenth century, the land along the river was dispossessed from a variety of Indigenous groups who inhabited the area, and settled by French, Spanish and German planters. They proceeded to plant indigo and then sugar cane, which they worked with enslaved labor. By the mid-eighteenth century, the banks of the Mississippi between New Orleans and Baton Rouge were completely carved up into sugar plantations. As elsewhere following the Civil War, Reconstruction was abandoned, forty acres were never distributed to the freedman, and any land seized from confederate plantation owners was promptly returned. Freedman were left to their own devices. Up and down the river, they founded small settlements—some known as freetowns—on tiny slivers of land in which Black people could acquire homes, usually in small parcels.

In the early twentieth century, white gold was replaced with black; the discovery of oil and gas quickly led to a downstream refining and petrochemical industry. Plantation owners cashed in, selling their land to petrochemical plants who now had analogous need of large tracts of land on the Mississippi River. As the plants grew and emitted more and more dangerous chemicals (including carcinogens like ethylene oxide, benzene, chloroprene, formaldehyde and many others), freetowns and other small sharecropper settlements became what are now often referred to as fenceline communities. Their Black residents would be most exposed to the toxic pollution, while hiring discrimination pushed them into subordinate positions in the petrochemical division of labor. Their largely white-dominated parish councils zoned land—often in transparently discriminatory ways—to facilitate state-subsidized industrial expansion without regard for the health of residents. The legacy of slavery is thus built into the geography, land tenure, division of labor, and political management of Louisiana’s petrochemical economy.

This is the reality currently being fought by many resident-led environmental justice organizations, including RISE St. James, the Descendants Project, Concerned Citizens of St. John, and a variety of state-wide organizations. Given that the Louisiana state government and its permit-granting agencies (regulatory would be misleading) treat the promotion of the fossil economy as their raison d’être, much of the environmental justice movement’s uphill battle has been focused on getting the EPA or courts to recognize and stop the deadly and disproportionate exposure of Black residents to toxic pollution. Although there have been notable local successes, such efforts have been stymied by conservative justices who—blind to history, social structure and cumulative emissions—hold the twisted logic that it would be racist to consider “disparate impact” in permitting toxic facilities.37Terry L. Jones, “Court permanently blocks environmental civil rights protections for Louisiana’s Black communities,” Louisiana Illuminator, August 24, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/08/24/environment-civil-rights/.

It is into this context that “clean fuels” enter. There are eight proposed blue ammonia and hydrogen plants in Louisiana; six are in the petrochemical corridor between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known as Cancer Alley. On average, the population falling within a two-mile radius of these plants is 50 percent black (and over 70 percent in one case).38Demographic data around the proposed facilities has been sourced from EPA’s Environmental Justice screening and mapping Tool, EJScreen. “EJ Screen: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool,” EPA, last updated November 18, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen. For context, the two parishes these projects fall under—Ascension and St. Charles—are each about 23 percent Black and the population of Louisiana is 32 percent Black. These residents are also, on average, in the eighty-fifth percentile nationally for exposure to toxic air pollution. Drawing concentric rings from the center of a project is a highly imperfect way to capture exposure to pollution for a variety of reasons, including the fact that it fails to differentiate those directly on the fenceline and those a bit farther away. And there is much local particularity in the geography of these projects and local settlement patterns. Nevertheless, this aggregate data captures the pattern in crude form.

For a finer-grained picture, we can look at the example of St. Charles Clean Fuels, a blue ammonia plant proposed on the banks of the Mississippi in St. Charles Parish. The $4.6 billion project, financed by a Danish “green” investment fund, claims it would capture over 90 percent of its carbon dioxide emissions.39Seifeld, “St. Charles Parish.” It would be located on two hundred acres of swampland behind Elkinsville-Freetown, a community in St. Rose founded by formerly enslaved people shortly after the abandonment of Reconstruction. Reflecting the pattern up and down the river, the adjacent plantation was sold to a chemical company early in the twentieth century.40Inclusive Lousiana; Mount Triumph Baptist Church; RISE St. James, by and through their members v. St. James Parish; St. James Parish Council; St. James Parish Planning Commission. United States District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana. Docket no. 2-23, 17 July 2023. Center for Constitutional Rights, https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/inclusive-louisiana-mount-triumph-baptist-church-rise-st-james-v-st-0. Today, two hundred chemical storage tanks are just a stone’s throw from homes on the other side of a rickety green fence. Residents complain of endemic toxic fumes wafting into their homes at night, and have endured repeated plant fires and leaks. According to the EPA (2024), the community ranks in the ninety-fifth percentile for respiratory risk due to pollution. Now they are faced with the prospect of living next to an ammonia plant, this one subsidized by the Biden Administration’s landmark climate legislation.

Residents of St. Rose have begun organizing against the project. Refined Community Empowerment, a community organization started by a longtime resident and teacher Kimbrelle Kyereh, has canvassed the surrounding neighborhoods and held several powerful meetings, each one larger than the last. A recent hearing on the project’s air permit, held by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, had to be shut down by the fire chief because of the overwhelming turnout. St. Rose is now the strongest organized opposition to the blue ammonia buildout in the state. Residents want to stop the new plant and obtain fenceline monitoring on the existing tank farm. Most residents I have interviewed feel overburdened by the existing pollution, to which they attribute respiratory problems, headaches, nausea and high rates of cancer. They cannot bear the idea of another plant, and are most worried about the additional toxic emissions—ammonia, nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, according to the plant’s permits—to which they would be exposed. Many are also concerned about the danger of carbon dioxide leaks from the new plant or connecting pipeline. The idea of putting a fossil gas-fed ammonia plant on two hundred acres of wetland next to an already overburdened Black community in the name of climate change seems patently absurd to them. They rightly view the blue ammonia plant as a straightforward extension of the petrochemical industry that has been poisoning them for decades. As one resident asked: “How can we have a blue ammonia plant when we’re already overburdened with chemicals?” And why, she asked, was the federal government “strengthening the hand” of the same “bullies” polluting them? Another resident felt urgency about dealing with climate change, but pointedly asked: “Who is doing all the dying for progress?”

These are good questions for liberal/left defenders of CCS. As the CCS boom refracts through the racialized class structure of Louisiana, it is thus not only reproducing but expanding the racially unequal distribution of toxic risk that has been the hallmark of the fossil energy regime. Louisiana may be an extreme case but it is not a unique one, as a large literature on environmental justice has shown.41For an overview, see Dorceta E. Taylor, Toxic Communities. Dorceta E. Taylor, Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility (New York: New York University Press, 2014). What could possibly justify the climate left supporting the fossil fuel industry instead of aiding the efforts of working-class Black residents to fight it?

The Politics of False Solutions

It is common to label “site fights,” such as the ones I have described above, as so much NIMBYism. I would point out that the epithet assumes what needs to be demonstrated—that it is only local residents who are protecting their parochial interests, while the projects themselves are in the public interest. I believe this is a very hard case to make for CCS projects, which involve enclosing public resources for private capital while externalizing all kinds of costs onto the public and environment. Even if one ignored the terrible toll in ecological destruction and pollution on human bodies entailed by this major infrastructural expansion, it is hard to even imagine the CCS buildout being carbon neutral for the reasons I have pointed out. It is, on the other hand, positive in the profit column for fossil fuel companies and prolongs their political and economic power, which will be used to blunt any actual transition from fossil fuels.

A state-wide coalition of mostly environmental and environmental justice groups called Louisiana Against False Solutions (LAFS) has been trying to amplify these local struggles and stop the CCS buildout. They critique CCS as a costly and untested way to prolong fossil fuels that will further degrade Louisiana’s fragile coastal ecology and expand environmental racism. They are animated by a desire to protect the people and the rich ecology of the Gulf South, which is otherwise doomed to be a fortified enclave for LNG export terminals, petrochemical plants and carbon dioxide injection wells as residents flee hurricanes and land loss in unmanaged retreat. They envision a just transition from fossil fuels, aided by investments in orphan well-plugging and offshore wind that could help to transition the existing workforce.

This anti-CCS coalition has faced stiff resistance, as the entire from a united oil, gas, and petrochemical industry that has become fully aligned behind CCS. At legislative hearings on CCS-related bills and task forces, powerful testimony from concerned residents has not moved the needle; the Louisiana Oil & Gas Association, the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, and the Louisiana Chemical Association–buttressed by dozens of industry lobbyists–have consistently defeated any effort to stop particular projects or reign-in the industry. Louisiana’s Trumpian Republican governor Jeff Landry and the Republican-dominated legislature (as well as most Democrats) are firmly behind the CCS buildout. This is not surprising as CCS is now part and parcel of the fossil fuel industry, to which the allegiance of Louisiana officialdom has always been steadfast. The question is: why should the left contribute any support or legitimacy to this endeavor?

Techno-utopianism as Theory and Strategy

I find it hard to imagine that any on the climate left would actually support the reactionary and destructive path I have outlined above. CCS defenders might argue that this scenario represents a grotesque and unjust application of an otherwise neutral technology that nevertheless has some promise if implemented more carefully and democratically by the public sector, perhaps with better-chosen sites and so on. Some might argue we should focus on DAC and not CCS more broadly. But I believe the reactionary decarbonization path underway in the Gulf has two important implications for carbon management techno-optimism, with or without such caveats.

First, techno-utopian visions of how CCS can be managed in democratic and public ways are so remote from reality as to be practically irrelevant. Left support for CCS will only add cover and legitimacy to fossil fuel and other corporate interests who are pushing this pathway regardless, and at no point will anyone involved in this industry take such views seriously. One can always say that, with some social movement in place and enough power exerted, a technology can be expropriated and repurposed to socialist ends and so on. But for this to be a critical theory rather than a sterile utopia, it must be demonstrated that this is an unrealized possibility within the current structure of society. Is there any basis in our current reality to believe that, in the next (say) twenty five years to thirty years there is a pathway from what we have now—state subsidies for fossil investment capital to earn windfalls in whatever CCS project offers a buck, regardless of who is harmed, what ecologies are permanently undermined, or whether it even contributes to net carbon dioxide reductions—to a democratically-run public sector carbon management system? It is difficult to see it. But even if that is what the techno-optimists are fighting for, one would still need to be against the present incarnation of fossil fuel-driven CCS and thus logically allied with current grassroots struggles against it.

This leads me to my second conclusion. The fossil fuel industry is pursuing CCS with bipartisan elite support. What seems like an unnecessary distraction is lending them more political cover. If we take seriously the idea that there must be an actual transition from fossil fuels and that it must be “just,” then the current CCS boom is exhibit A for how not to achieve that. This also means that defensive struggles against the false solutions of reactionary decarbonization are very much a necessary part of climate justice, or emancipatory decarbonization. Such defensive coalitions will only partially overlap with coalitions for real solutions: while some participants will be rural and conservative folks who want neither carbon management nor climate action of any kind, other groups—including the environmental justice movement—have been at the forefront in the fight against fossil fuels. Others may be on the fence. Pushing dangerous and destructive CCS infrastructure down their throats is not only objectionable on multiple grounds, but it alienates allies and weakens potential support for emancipatory decarbonization.

Then again, perhaps the techno-optimists are right; maybe researchers in a government lab will come up with an economical vacuum cleaner powered by renewables that turns atmospheric carbon dioxide into piles of rocks that can be stuffed into abandoned coal mines. I doubt that will overcome the laws of capital or thermodynamics (and it wouldn’t help with toxic pollution). But, sure, let’s not rule it out. In the meantime, why don’t we focus on building power against the fossil fuel industry, a social force we know to be utterly incompatible with a healthy and just life on Earth?