Our Bob Dylan

One of the most frustrating, if entertaining films of 2024 was James Mangold’s Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown. Timothée Chalamet embodies a figure of Dylan that is as physical as it is discursive. His performances and singing are certainly meant to be precise, not interpretive, but the young movie star manages both. Monica Barbaro and Edward Norton are equally authentic and precise as Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. Yet it is with Barbaro as Baez that we start to realize the inherent flaws in the edifice. Baez, an exceptionally important historical figure in her own right, is simply a means to an end in this film (in spite of Barbaro’s performance). Said end is a new myth of Dylan for a new generation of young people actually buying physical music again. You can save accuracy for the birds and bees; Dylan, well-ensconced in the making of this film, had his mind on his money and his money on his mind. This new stunningly apolitical and misogynist myth of Dylan will be explored below, but the principal aim of this writing is to serve as a vital corrective.

In doing so, I will start by attempting to show Bob Dylan’s public historical role as an artist and storyteller and why it is important, in particular in this case, to get it right. Setting him in his proper historical context and in relation to radical left politics, I will then engage with what Dylan scholarship refers to as the “figure of Dylan.” There are a lot of truths and tall tales in the myth of Dylan, yet the film reinforces the latter—even adding a few whoppers to the mix. Indeed, the myth of Dylan is perhaps even more established in cinematic or televisual form than musically speaking. After this engagement, I provide not an alternative myth of Dylan, but rather a historiography that complicates, if not obliterates, the primary aspects of this myth. Expanding on themes developed in the first part, I will examine Bob Dylan’s relationship with the radical left and counterhegemonic culture as such. I show how the film not only misconstrues his and his comrades’ activism but renders it a frivolity. To add to this, I set my lens to panorama and briefly engage what I call the “long sixties” as a whole, before arriving finally at a key moment, what Dave Marsh called the moment when “rock and roll” became rock. This was when Dylan “went electric” at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

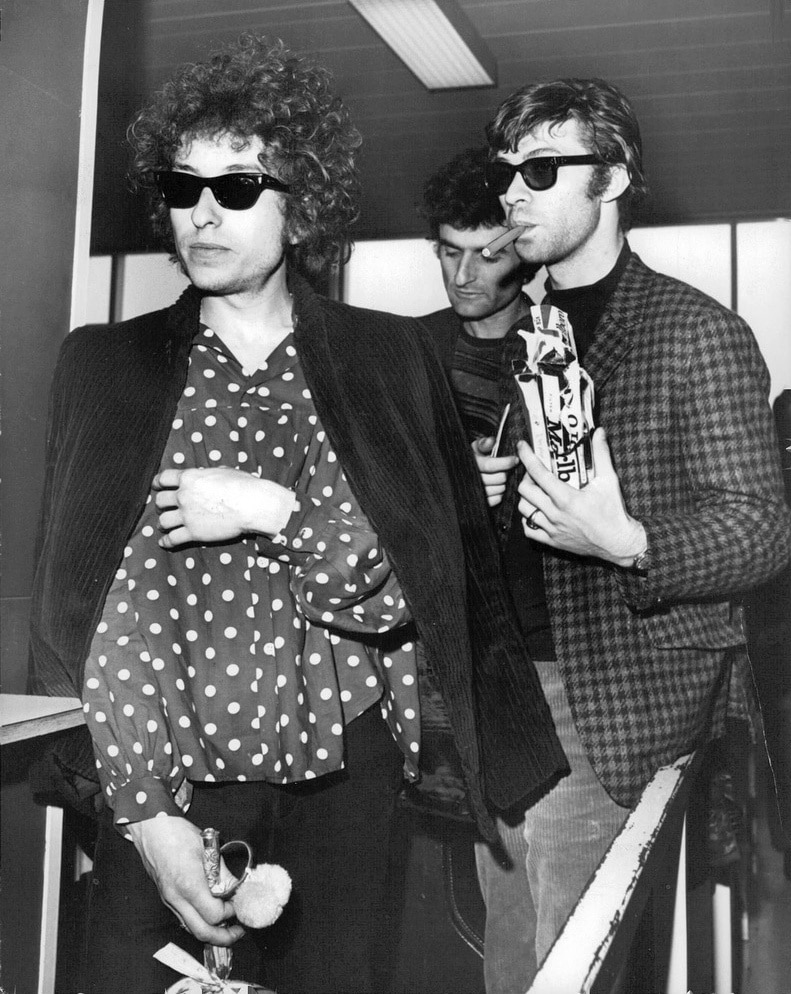

Bob Dylan is a product of social relations set in motion and sustained by the far left, understood broadly. Folk music and its attendant cultures were produced by an infrastructure of dissent that was often instrumentalized by, but could never be reduced to, the Communist Party. Trotskyists, Christian socialists, anarchists, even strikingly apolitical existentialist types all swam through the folk scenes emerging in the late fifties and early sixties. They did so first in New York, then in other major cities such as Toronto, whose Riverboat birthed the careers of Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. Dylan thus came of age as a cultural producer in which the logic of the left was common sense. Dylan was at a time very politically active, spending much of summer 1963 travelling and performing for the civil rights movement in the South. He was socially close to all flavors of the left and had ties to The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in particular. He had a healthy suspicion of the Communist Party types who would attempt to instrumentalize him and pigeonhole him. Yet if he would move beyond this scene he did not (at least at the time) give up its values. Indeed, like much of his generation’s rejection of the mores of the old left for the culture of the new left, his shift in focus was in keeping with trends in radical culture in general. This is all to say that he is our Dylan. Dylan came of age and learned his sensibility in our movement.

Dylan’s midsixties work (including going electric) is often misrepresented, thus resituating him as an apostate to the political left. I debated Bill Crane on these points nearly ten years ago in the pages of Red Wedge.1Bill Crane, “Dylan as Poet,” Red Wedge, October 17, 2016, https://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/dylan-as-poet-crane-nobel; Jordy Cummings, “The Joker and the Thief,” Red Wedge, June 21, 2017, https://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/the-joker-and-the-thief. Debates about Dylan’s political turn at this time have much to do with the lyrics of a few specific songs, notably “My Back Pages,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” and, to an extent, “Positively Fourth Street” and “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding.” All four songs, in particular “My Back Pages” and “It’s Alright Ma…” are explicit, thinly coded references to his turning away from the Popular Front left. A common reading, including Bill’s, is that Dylan’s refrain of being “So much older then, younger than that now,” was that Dylan’s certainty around ideas of social justice was no longer the case, and he was now ensconced in a detached skepticism. However, my own reading, in keeping with Dylan’s continued insistence that he still wrote protest songs, was that “My Back Pages” was a critique primarily of the tactic of fighting for incremental change or “formal equality” as opposed to substantive equality. Dylan was sympathetic to Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s perspective in 1964 and was critical of the Civil Rights leadership’s acquiescence in what he saw as respectability politics more than the bourgeois Democratic Party’s refusal to seat them. Hardly the move of an apostate. The debate, to a large extent is less qualitative—most Dylan scholars, let alone fans, think that this is some of the most vital music of his career. Dylan going electric and all that entails, along with his move away from didactic songwriting is seen, in this lens, as bourgeois individualism. Yet what could be more critical of the bourgeois individual than to bemoan the contingency of life, “like a rolling stone.” Hence, my contention that this is to miss the forest for the trees and to imbue the storyteller with the power of a prophet. Dylan going electric is a historical moment, first and foremost in a formal sense. While eschewing a strict foundationalism, this was the moment in which all of the ingredients of what the critic and Marx translator David Fernbach referred to as a “rock aesthetic.” Fernbach defined this as the domination of rhythm over melody, musical melody over vocal (if not lyric), and, in particular, the primacy of the rhythm section, the bass guitarist and drummer.2Andrew Chester [David Fernbach], “For a Rock Aesthetic,” New Left Review 1, no. 59 ( January/February 1970): https://newleftreview.org/issues/i59/articles/andrew-chester-for-a-rock-aesthetic; Andrew Chester [David Fernbach], “Second Thoughts on a Rock Aesthetic: The Band,” New Left Review 1, no.62 (July/August 1970): https://newleftreview.org/issues/i62/articles/andrew-chester-second-thoughts-on-a-rock-aesthetic-the-band; Richard Merton, (Perry Anderson), “Comment on Chester’s ‘For a Rock Aesthetic,’” New Left Review 1, no. 59 (January/February 1970): https://newleftreview.org/issues/i59/articles/richard-merton-comment-on-chester-s-for-a-rock-aesthetic.

Fernbach made these points in a somewhat infamous set of debates in New Left Review with Perry Anderson. The two of them both writing under pseudonyms is telling of the New Left’s insecurities about its cultural sensibility. In response to Anderson concentrating on the political and cultural significance of rock music and counterculture, particularly the breaking down of barriers between audience and performer, he argued against establishing a formal aesthetic criterion. Fernbach, on the other hand, argued that to allow for what was specific about rock music, one had to establish its distinctive form. Agreeing with Anderson’s take on political significance, Fernbach nevertheless took issue with the instrumentalism of Anderson’s take. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards didn’t write “Street Fighting Man” due to being close to the Trotskyist International Marxist Group (IMG). They became close to the IMG for the same reason they bemoaned the lack of fighting organization in a “sleepy London town.”

This then raises a question for the left, defined broadly: who is our Bob Dylan? As there is no singular Dylan, the figure of Dylan remains contested as much as all culture does. But I submit that the facts and framework are with us, from the standpoint of actually existing historical impact as well as “checking the boxes” of any valid aesthetic criterion. The question is thus raised: why Dylan? At the time and for at least a decade after the period portrayed in A Complete Unknown, it would be no exaggeration to make the claim that the left, in both its old and new forms, saw Dylan as an inspirational figure. It would be equally apropos to make that claim today, at least in some quarters. Well after Dylan’s alleged apostasy, Huey Newton did deep dives into his lyrics, in particular “Ballad of a Thin Man.” Dylan in turn was one of the few white musicians to do solidarity work and write songs for George Jackson. Later on, he appeared at benefits for Salvador Allende.

More directly, Dylan, with his colleagues and cothinkers invented a musical and cultural form.3It is virtually undeniable that, when “going electric,” and in particular on his tour and recordings with the musicians who later were known as “The Band,” Dylan and comrades were making music the likes of which the world had not heard. Perhaps the dissonance of the guitars was familiar in some Chicago blues and even garage rock. Perhaps the lyrics were of a piece with the impressionistic move of midsixties folk and folk rock, though far superior at any rate. The use of organs may have been sonically informed by Blue Note Hard Bop musicians, but was more reminiscent of gospel. And of course the drumming was adapted from pioneers like Charlie Watts and Ringo Starr. The combination of all these things, as Dave Marsh put it, was the transition from rock and roll to Rock music, or a “rock aesthetic.” His role has been mystified to a point of absurdity, but his significance as a historical actor, if anything, is underrated. If we take seriously the role of cultural production in constituting counterhegemonic politics through countercultural practices, Dylan is to this constellation a figure on the level of Lenin for the Russian Revolution or DaVinci in the Renaissance. He is not a mythologically singular figure, but he actually is a historically singular figure. Indeed, and as I am trying to show, the myth of Dylan obscures his achievements and limitations. From the world-shaking to the quotidian, Dylan had a part in every major cultural shift in the English-speaking world and beyond in the last half century, even showing relevance with his COVID-19 opus, “Murder Most Foul,” which I engaged in New Politics.4Jordy Cummings, “Painting the Passports Brown: Listening to Dylan During COVID-19,” New Politics 18, no.1 (Summer 2020): https://newpol.org/issue_post/painting-the-passports-brown/. He was even the first person to get the Beatles high. Yet the underlying politics of all this are obscured, that of the cultural as well as political shift—from “folkie” to hipster, from old left to new left. By failing to connect the cultural to the political shift (and indeed trivializing the cultural shift), critiques from the left thus appear as individualist and perhaps implicitly anticommunist.