Street Art, Place-Making, and Anti-Capitalist Spatial Activism

Notes from Berlin

July 22, 2020

This essay brings together two of my ongoing interests, one from my political life and one from my scholarly life. On the one hand, I am interested in creative forms of resistance against capitalism, especially bottom-up forms of resistance available from outside the domains of formal policy or electoral politics. On the other hand, much of my recent research concerns how street art can contribute to place-making and place identity. I am interested in exploring how street art constitutes space rather than just adoring or defacing it. Most writers see graffiti and street art as additions to space, which overlay it and decorate or disfigure it. For example, Rafael Schecter, an anthropologist specializing in graffiti and street art, argues that street art is “adjunctive and decorative,” serving as an addition to a “primary surface” with “fundamentally ornamental status” 1Rafael Schacter (2016), “Graffiti and Street Art as Ornamentation,” in J. I. Ross (editor), Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art. Routledge, 244.. My ontology of street art is diametrically opposed to this view. I argue that the role of street art is not additive but transformative. Street art can be a substantial intervention into place identity. It can be a restructuring force that changes how a space is legible or interpretable to its users, as well as how that space forms a territory with insiders and outsiders. Here, I look at the case of Berlin, and more specifically at how street art is used in Berlin as a tool in resisting the capitalist commodification of space, and in creating anti-capitalist alternative spaces.

Divided Berlin functioned, to the extent it did, by tightly and elaborately controlling the flow of its two sets of residents, and by carefully surveilling and overseeing this flow top-down, partly through the arrangement of the built environment, including walls, gates, checkpoints, surveillance towers, wiretapping, and so forth. Now, it is a city marked by discontinuities, ruins, and random empty spaces produced by its history of being bombed, ripped in half, and roughly and imperfectly sutured back together after the fall of the Wall. Andreas Huyssen, one of the most prominent commentators on the landscape of Berlin, calls Berlin a city of voids—underdetermined and emptied spaces left behind by the series of abandonments and removals from the Nazi era, the divided years, and reunification.2Andreas Huyssen (1997), “The Voids of Berlin,” Critical Inquiry 24:1, 57-81. These voids open themselves to bottom-up occupation and various creative and dynamic repurposings of space. Berliners have seized upon the indeterminacy and disorganization of the city and used it as an opportunity to create a city-wide, constantly ongoing experiment in claiming space. The material landscape of Berlin is constantly changing, by design. Berliners love to work on and transform space, in ways that are designed to be temporary and dynamic.

Despite having more art galleries per capita than any other city in the world3Alison Young (2013), Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. Routledge, p. 76., Berlin’s main canvas is the city itself. Berlin is a gigantic, city-wide, collective, decentralized, dynamic artwork. Covered from top to bottom with graffiti, street art, and political marking and signage, the three-dimensional city has been overlaid by a second, ever-changing, spectacularly beautiful city created by its residents. Theorist of street art Alison Young observes that “artists in Berlin seem to view any area surface as a potential writing surface and to a much greater extent than in other cities”4Alison Young (2013), Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. Routledge, p. 75 . I am interested in how street art in Berlin is used as a tool with which to negotiate the politics of space, occupation, and mobility in the city, through place-making interventions. In particular, I will examine several different ways in which street art functions to resist the capitalist colonization of space in the Berlin.

Spatial Politics in Berlin

Berlin has a unique relationship to both capitalism and communism. Not only is it the only city to have been split down the center into a capitalist half and a communist half, but it is distinctive in that both these economic and cultural orders were imposed by occupying forces in the city, and both were experienced by Berliners as involving dramatic, externally imposed restrictions on their ability to live in, use, and move through space. While Berliners on each side of the Wall experienced different restrictions and had different resentments, there is evidence that what both sides resented most was not capitalism or socialism per se, but rather the restrictions on mobility, the spatial claustrophobia and seizure, and the lack of spatial freedom. East Berliners particularly resented the extreme surveillance and restrictive policies that curtailed mobility, while West Berliners resented the housing shortages, isolation, limited opportunities, high housing costs, and restricted mobility that came with living inside a walled and stranded city.5For detailed empirical support for these resentments, see Kukla, Rebecca (2019), Repurposed Space in Berlin and Johannesburg, Master’s Thesis, Department of Geography, CUNY Hunter College. When the Wall came down, people on both sides flooded over the former border, happy to have increased mobility and agency over their use of space. Thus, arguably, Berliners’ resentments during the Cold War were never primarily directed at communism or capitalism as economic and political systems per se, but in the first instance at the impositions on spatial freedom that both orders brought along with them. Capitalism won the Cold War, and Berlin is now a fundamentally capitalist city, but that doesn’t mean that its residents have forgiven capitalism for its spatial sins.

One of the most famous murals in the city is Victor Ash’s “Astronaut/Cosmonaut,” which represents and reflects upon the city’s history of foreign occupation and division. This giant mural represents the space race, and in turn it portrays Berlin itself as a pawn in a territorial battle between Russia and the United States. The landmark work reflects upon Berlin as a space caught between occupying forces and between communist and capitalist political ideologies.

Figure 1: Victor Ash, Astronaut/Cosmonaut (2007). Photo from wikicommons.

Over the past decade or so, Berlin—famously a ‘poor but sexy’6The moniker given to the city by former mayor Klaus Wowereit in 2002. city known for its disproportionately affordable and plentiful housing and strong renter-friendly policies—has increasingly become desirable to foreign investors and property developers, looking to take advantage of the city’s popularity with immigrants and its still-empty spaces. Fifty thousand new residents arrive each year, not counting refugees, and many of these are arriving from other wealthy countries. Berlin currently has the fastest rising real estate prices of any city in the world (Collinson 2018). Foreign development companies are seizing land and buildings at a dizzying rate, creating a housing crunch that Berlin has long avoided, and often evicting beloved leftist institutions such as cultural centers, anarchist bars, feminist housing projects, and the like. Gentrification in many neighborhoods, especially those clustered along the former Wall, is escalating quickly.

Berliners are actively resistant to these co-options of space. Large property developers such as Mediaspree face ongoing organized protest and resistance, both formally and through vandalism and graffiti. Multinational companies perceived as intertwined with neoliberal capitalist technocracy and the commodification and monetization of space and mobility such as Google and Uber meet with particular resistance in Berlin. On September 7, 2018, squatters occupied the new Google offices in Kreuzberg, and anti-Google graffiti in particular festoons the city. Because of its Cold War history as an occupied city marked by spatial restrictions, Berliners experience this new wave of investment, development, commodification, and seizure specifically as a form of spatial colonization, where capitalism and its capacity to ‘eat up’ space from the outside is the colonizing force.

In Berlin, residents are consistently engaged in fighting for the right to move into urban space, move through it, occupy it, and control its use from the bottom-up. When Berlin residents object to something, occupying space is their first line of attack. Both East and West Berlin had active squatting and occupation movements under division, designed to resist the top-down control of space. With many buildings unoccupied and semi-destroyed after World War II, there were plenty of places to squat on both sides, and the city did not have the financial resources or organization to fix the ruined buildings. When the Wall was torn down, huge areas that had been useless because they were cut through the middle by the wall or squeezed right up against the surveillance towers and armed guards of the Death Strip suddenly became empty space available for squatting and developing. Infrastructure that had been doubled to accommodate the split city, such as power plants and hospitals, shut down, and then often became occupied by squatters.

Many of these squats evolved into what Berliners call hausprojekts, or living spaces based on various communal and collaborative arrangements, and designed to minimize participation in the capitalist commodification of space. Most of these hausprojekts host musical events, parties, communal meals, as well as events designed to serve the indigent and refugee community. Different hausprojekts have different politics and arrangements, but in all of them, residents care communally for the space, make decisions together, eschew property ownership and for-profit enterprises, and try to keep costs for residents down to a minimum.7For an excellent comprehensive history and sociology of squatting and hausprojekts in Berlin, see Alexander Vasudevan (2015), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin. John Wiley & Sons.

The squats and hausprojekts of the city form the base for Berlin’s spatial activist community, a informal network of groups and individuals that share a commitment to a loosely linked set of issues, including anti-gentrification, alternative non-capitalist forms of occupation, free migration and mobility across borders, privacy (which encompasses anti-surveillance as well as a culture of consent), and anti-bigotry. This grab-bag of issues tends to be unified around objections to the top-down control of space and motion, including freedom of bodily motion and freedom from unwanted intrusions. Since almost all of these groups conceive of themselves as anarchist in their deliberative structure and political commitments, there is no real formal or hierarchical organization to them. The term ‘soli’, short for Solidarität or solidarity, is routinely used to mark events and spaces that participate in this loose and mutually supportive network.8There is a monthly newsletter of ‘soli’ music shows and other events, for instance. The ‘soli’ indicator has no formal definition and whether something counts as a soli space or event is ultimately a matter of self-identification. But the term marks general sympathy with anarchism, anti-capitalism, and leftist spatial activism, as well as marking a mutually supportive informal social network. Soli squat houses and other soli organizations will often team up to organize for some specific cause, particularly to protest evictions and property developments, but these affiliations are ad hoc.9Some of the leftist groups in Berlin that share commitments to anarchism, fighting gentrification, free borders and the like specifically identify as “Anti-Deutsch”, which signifies their desire for an end to Germany as a sovereign state, based on their general commitment to anarchism and open borders combined with a belief that Germany in particular is unsalvageable because of its past. The anti-Deutsch groups are also committed to a strong sovereign Israel (which sits oddly with their general anti-borders commitments), and often take positions seen as Islamophobic. This is a separate leftist network from the ‘soli’ network. Newcomers to Berlin may not immediately notice the distinction between the two leftist networks given the overlap between their issues and their aesthetic, but they are in fact quite separate. My focus is on the ‘soli’ groups and spaces.

In Berlin, residents are consistently engaged in fighting for the right to move into urban space, move through it, occupy it, and control its use from the bottom-up.

The city is often willing to compromise with squatters and spatial activists, for two reasons. First, it is part of the ethic of occupation in Berlin to claim space partly by working on that space, by investing labor in repairing and repurposing it. “Instandbesetzung” (reclaim and repair), a term coined in 198010Alexander Vasudevan (2015), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin. John Wiley & Sons., is an ethos in the city. Many squatters make legitimate claims on spaces, which stand up to legal challenge, by making them habitable. Since the city is poor, this repair work is valuable. Second, the whole cycle of occupation and repurposing is so deeply part of the aesthetic and character of the city that attempts to displace occupiers are deeply unpopular. After various failed centralized development plans, the city for the most part seems to accept that decentralized, bottom-up spatial appropriation is central to what gives Berlin its place identity.

Street Art as Place-Making

In the most general sense, street art—and I will by stipulation count graffiti, informal signage, and tagging as forms of street art here—visually reorders and restructures space. It imposes patterns and meanings onto a space, and in doing so it may change the experienced and usable form of the original space.

I will look at three distinct ways in which street art functions to restructure urban space in Berlin, each of which is used to resist the capitalist colonization of space:

- Through explicit messaging and political content. Art and graffiti that have representational content can directly give meaning to a space, and can give us clues about what sorts of practices and people belong and don’t belong in it. Even a simple act of tagging is an intervention into the territorial structure of a space—a performance and a marker of a claim upon a space.

- Through reshaping how we attend to and move through spaces, and thereby shaping the phenomenological form and temporality of space. Artists often mark parts of urban space that are typically mere background or outside our attention, such as underpasses, sewage pipes, the tops of walls, and so forth. This can shift how we direct our attention as we move through a space, which can in turn radically alter its perceived form. It can also change our movement through a space, as we move close to and linger by a small piece for instance. Moreover, art in unexpected places can slow us down in spots that were originally designed just to be passed through, and intimidating art can make us avoid or speed past an area. Thus, art can alter the temporal form as well as the spatial form of a place.

- As a tool of spatial secession—a term I will discuss in detail below. Art can be used to visually signal that a space has intentionally separated itself from the rest of the landscape. Street art helps turn spaces into specific territories in which some people belong and others do not. Street art, as we will see, creates a shifting array of insiders and outsiders.

I turn now to how all three of these function in Berlin as place-making interventions that resist the capitalist commodification of space.

Anti-Capitalist Place-Making Through Explicit Content

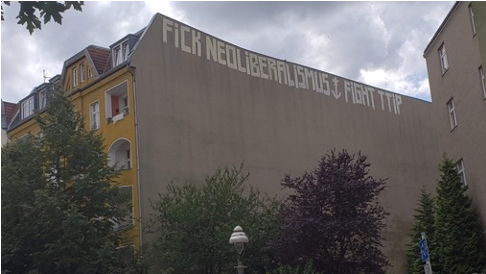

Figure 2: Apartment Buildings in Wedding. Photos by author, 2018

Berlin is covered with explicitly anti-capitalist, anti-gentrification graffiti and art, as well as explicitly pro-mobility and explicitly anti-authoritarian art. Lots of Berlin graffiti mocks the trappings of capitalism such as Disney and television advertising. Recently, there has popped up quite a bit of graffiti supporting Rojava, the socialist self-declared free state in northern Syria. A great deal of the work explicitly resists the commodification of space. Much of the graffiti and signage in the city contains the word “Bleibt” and its cognates, which literally means ‘stay’ or ‘remain,’ but connotes defiant refusal to leave, or survival. This word is closely linked with the politics of occupation and anti-gentrification in the city. Graffiti and art incorporating the word “Bleibt” often memorializes anti-capitalist spaces, especially squats and hauseprojekts, that were shut down successfully by developers. Another word that decorates the city is “Besetzen”, or roughly “occupy”. For Berliners, capitalism is linked with the top-down control of space more generally. Accordingly, much of the graffiti simultaneously takes on capitalism along with authoritarianism, state control, and border policing. “ACAB” (All Cops Are Bastards) graffiti, for instance, or its numerical version “1312,” standardly appears next to “Bleibt” graffiti, and anti-gentrification messages.

For instance, in the heavily gentrified Prenzlauerberg neighborhood of former East Berlin, a former squat on Kastinallee that has now been turned into a legal hauseprojekt and cultural center is nestled up against expensive boutique clothing stores and coffee shops. The building features a particularly vivid series of signs, which translate to slogans such as “Capitalism normalized kills/destroys” “Free movement for all people! Foreclosure and depreciation are lethal!” and “Air, Water, and Affordable Rent.” Several of these slogans directly link capitalism to mobility restrictions.

Figure 3: Capitalism Normalized Destroys/Kills, Prenzlauerberg, 2018.

In Kreuzberg at south bank of the Spree, the celebrated street artist Blu, known for his anti-capitalist, anti-gentrification graffiti, painted two works on the sides of abandoned warehouses in 2007 and 2008: “Shackled by Time” and “Take Off that Mask.” Both quickly became among Berlin’s most iconic works of public art. The works vividly represent the top-down constraints on autonomy and identity that capitalist institutions demand. In the top right, the words “RECLAIM YOUR CITY” mark the works as a performative act of claiming urban territory. The work was above a squatter camp, and the phrase in effect spoke directly to the squatters as well as to passers-by.

In 2014, the squatted land next to the murals was purchased by Mediaspree, among the most notorious and resented of the gentrifying developers, and they had the camp cleared. In a brazen act of forced commodification, the company published brochures for their upcoming condo developments that featured Blu’s murals, implying that the view of the iconic works would be one of the selling points of the new residences. Blu was thus coopted into helping turn his own anti-capitalist, space-claiming works into part of a commodified aesthetic that functioned in direct contradiction to the intended meaning of his art. In response, in 2014, with the help of friends, Blu painted over his own artwork in black, leaving behind only the words “YOUR CITY” in the top corner, destroying his work rather than letting its meaning be stolen and subverted.11Lutz Henke (2014), “Why We Painted Over Berlin’s Most Famous Graffiti,” The Guardian December 19, 2014. The blacked-out site of “Take Off That Mask” has since been festooned with a giant, profane middle finger that points at the construction site.

Street art has thus been used, through its explicit content, to transform the spatial meaning and place identity of this site several times. The place started out as part of the “dead zone” of the city, too close to the wall to be useful. Blu took what was still basically a non-place, with nothing that specifically attracted visual attention, and turning it into a place, a focal point, through his art. The murals turned the squatter camp underneath into a public performance of claiming the right to the city and resisting the commodification of space. Mediaspree then turned this very feature of the space into a way of intensifying its commodification. Mediaspree’s use of the image of Blu’s work was a colonization of his meaning, and of the space he was both protecting and trying to create. Until it was blacked out, the art remained a visual focal point, but one used to attract potential buyers and capital. Now that the art has been removed, the giant black wall with the profane finger transforms the meaning of the space once more, turning it into an active public battleground over the right to the city, and a visual exploration of questions about the limits, if any, of capitalist colonization. Because the art was already famous, his blacking-out did not turn the place back into a non-place, but rather changed its meaning and its territorial claims yet again. Blu’s friend Lutz Henke, who helped him black out the work, writes, “Because it needs its artistic brand to remain attractive, [Berlin] tends to artificially reanimate the creativity it has displaced, thus producing an ‘undead city’… The white—well, in this case black—washing also signifies a rebirth: as a wake-up call to the city and its dwellers, a reminder of the necessity to preserve affordable and lively spaces of possibility, instead of producing undead taxidermies of art.”12Lutz Henke (2014), “Why We Painted Over Berlin’s Most Famous Graffiti,” The Guardian December 19, 2014. The remaining phrase, “YOUR CITY,” is pointedly ambiguous—it could be read as a lamentation aimed at Mediaspree and any future residents of the condos, or as a public call to action.

Figure 4: Blu, “Shackled by Time/Take Off That Mask”, uncredited 2012 photo.

Figure 5: Blacked Out Blu, photo by author, 2019

Anti-Capitalist Place-Making Through Redirecting Attention

A more surprising and less obvious way in which street art can shape space is by shifting our attention, pace, and movement as we travel through a space. Street art can change the direction of our gaze, and alter, slow down, or speed up our motion through space, effectively changing its experienced form and temporality and restructuring its pattern of salience. Berlin graffiti artist Brad Downey thinks of himself as a ‘sculptor’ of urban spaces through his use of art to shift attention in this way. His experience as a skateboarder was what first made him aware of how different kinds of movement through and attention to a space could shift place identity.13Alison Young (2013), Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. Routledge. argues that graffiti can effectively constitute an alternative city within a city—a city that flips form and content depending on how we direct our attention.

This kind of attention-shifting art is often used to direct our gaze to ruins, undersides, and other features of the environment that were not designed to be attractive for commodification purposes. One of the powerful effects of Berlin’s street art is that it can instantly fill the voids and empty spaces that are strewn throughout the city. The remnants of the wall and empty gashes in the city and the abandoned factories and so forth can become works of art. This focuses our attention on parts of urban space that we would otherwise not have really noticed—it turns non-places into places. In an important sense, then, the graffiti and street art of Berlin dramatically changes the experienced, phenomenological morphology and organization of the space of the city itself.

In an important sense, then, the graffiti and street art of Berlin dramatically changes the experienced, phenomenological morphology and organization of the space of the city itself.

Many of Berlin’s most noted street artists play with this attentional restructuring of space. The Berlin Kidz crew, whose work covers the city, specializes in tagging unexpected, hard-to-reach places, such as the tops of buildings visible only from trains. Artist Alias specializes in stencil work, and he creates lonely, small figures in busy, shared public spaces that we typically rush through, requiring us to move in close at unusual angles to see them. According to his Facebook page, his mission is “Pasting pieces of intimacy in the public space.” His work is especially powerful for transforming the form of space, because he turns open, anonymous places into shared, small, intimate spaces that draw us into an emotional scene. The piece in Figure 6 turns the public space under a staircase into a private room in which we can linger for a private interpersonal encounter.

Figure 6: Alias, “Hiding”, 2012. Photo reprinted with permission of the artist.

Berlin’s distinctive architecture combined with its history of destruction and abandonment lends itself to these attentional restructuring projects. The Altbau buildings lining almost every street were designed to maximize residential density, stretching far back from the road, with no windows on their sides. Many of these windowless sides are now exposed because of bombing. They create natural palates for art and tagging, which shifts what was designed to be hidden and merely utilitarian into the visual forefront. In Figure 7, a windowless wall next to a bombed site in Kreuzberg combines a commissioned 2007 work by the Belgian artist ROA, and a second detailed mural, as well as anti-police graffiti along the top, and the distinctive red and blue tagging of Berlin Kidz towards the back. What interests me here is how a space that was supposed to be hidden and merely functional has become a layered place with multiple meanings and a complex structure, worth lingering over. This spot is now an ‘attraction’ and it has developed a place identity that was not built into the original architecture.

Figure 7: Art by ROA, Berlin Kidz and others. Photo by author, 2018.

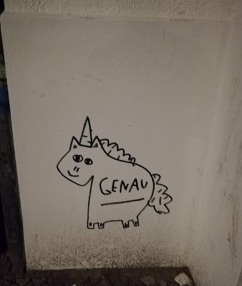

An anonymous artist in the Neukölln neighborhood, who I think of as the unicorn tagger, uses spots that do not typically draw attention and are at unusual heights, such as the bottoms of doors, bridge support beams, the corners of walls, and lamp posts, for a series of rough-drawn unicorns with slightly different facial expressions, saying different things (see Figure 8). The series makes us stop in odd places and hold our body at unusual angles in order to look at the drawings. Once you start noticing the unicorns, they pull you through the space of the neighborhood according to a different path, as it becomes compelling to look in out-of-the-way places for more of them, in order to ‘collect’ them as one moves around in space. Like so much Berlin art, the unicorns are completely unsigned, so they are a place-making intervention into space and not an attempt at building a commodified brand.

Figure 8: The Neukölln Unicorn Tagger, photos by author, 2019 and 2020

These intentional restructurings of space often have no overtly political content. Berlin Kidz, for instance, almost always stick to abstract forms. All the same, this type of art can function as a kind of anti-capitalist spatial activism, for two reasons:

First, by altering the shape and identity of space bottom up, it can serve as a kind of space claiming and territory building. Developers and city planners design space to have a specific form. Altering that form is a kind of bottom-up claiming of a space and its meaning and use. Earlier I introduced Berlin squatters’ key concept of Instandbesetzung, or reclaim-and-repair. Typically, Instandbesetzung involves fixing up and rebuilding buildings and then claiming rights of occupation over them in virtue of having made them livable. But the kinds of artistic interventions I am examining in this section can be interpreted as a kind of aesthetic Instandbesetzung, wherein artists claim city space by reshaping its form at the experiential level.

Second, these kinds of artistic interventions can be used to disrupt the city’s attempt to control its look, and to curate its aesthetic self-presentation for tourist consumption. In Berlin, unlike in many other cities, tagging or painting over other artworks is not a norm violation; indeed Berlin’s multilayered and chaotic look is one of its aesthetic hallmarks. But the political effect of overlaying in this way is different when the original work was designed to showcase and market the city. The East Side Gallery, one of Berlin’s main official tourist attractions, is a fascinating case study. The gallery consists of 1.2 kilometers of the original Wall. Each neat square of the wall contains exactly one commissioned artwork. The gallery features aesthetically and politically unchallenging pieces all neatly lined up, often with bland messages of peace and unification. Although access to the gallery is free, there is no mistaking that the display is designed to generate revenue for the city. Souvenir shops and kitschy tourist attractions like ‘pirate cruises’ are gathered along the length of the gallery. However, local artists and taggers have here and there disrupted the orderliness of the gallery, not just by painting on top of the commissioned works but by noticeably disrespecting and crossing over the boundaries between the squares. Most of the overlaying is pointedly rough and often crude. By attentionally disrupting the commodified aesthetic of the space, these overlays experientially reshape the space, returning it to the bottom-up decentralized (dis)order that characterized the original Wall and still characterizes most of the city, and vividly resisting, at the visual level, the city’s attempts to marketize the street art aesthetic and the city’s history.

Figure 9: Commissioned artworks along the East Side Gallery. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 10: “Artistic” and “I love sluts.” Tagging over several squares of commissioned art at the East Side Gallery. Photos by author, 2019.

Interestingly, the East Side Gallery is openly mocked by street art in other parts of the city, which critiques it as standing for the commodification of space for tourist consumption in Berlin. For instance, Figure 11 shows an unsigned work along the bottom of a wall filled with uncommissioned street art in the Fredrichshain neighborhood, in which a tourist is portrayed as trying to find his way from the vibrant art-filled wall he is under to the (less artistically interesting) East Side Gallery.

Figure 11: “How do I get from here to the East Side Gallery?”, photo by author, 2019.

Anti-Capitalist Place-Making Through Spatial Secession

In her book, Iron Curtains: Gates, Suburbs, and the Privatization of Space in the Post-Socialist City, architectural theorist Sonia Hirt, who specializes in post-USSR landscapes, offers a typography of forms of what she calls “spatial secession,” which she defines as the “willful act of disjoining, disassociating, or carving space for oneself from the urban commons.”14Sonia Hirt (2012), Iron Curtains, Gates, Suburbs and Privatization of Space in the Post-Socialist City Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, p. 49. For Hirt, spatial secession in its various forms is a product of the end of the communist occupation of space. When the top-down control of space associated with the USSR diaspora ended in cities across Europe, she argues, economic volatility combined with newfound spatial freedom and a relatively unchecked rush of capitalism combined to encourage spatial secession, which produces privatized and anti-democratic spaces that are exclusionary and not integrated into the surrounding urban ecology.

While I find Hirt’s concept of spatial secession powerful, I think that in Berlin, spatial secession is used for almost the opposite purpose to the one Hirt describes—namely, not as an expression of unchecked capitalism, but to protect spaces from the colonizing forces of capitalism and gentrification. Hirt assumes that the capitalist unit of spatial commodification is the individual dwelling. But in Berlin, as in so many other gentrifying twenty-first-century capitalist cities, property developers often try to seize and impose top-down planning on whole swaths of the city, creating ‘entertainment districts’, residential developments, planned neighborhoods, and the like. In this context, capitalism, not communism, is the homogenizing, top-down spatial force. Berliners use spatial secession to carve out and protect spaces from capitalist colonization, and to enable non-commodifying forms of spatial use to flourish. Most interestingly for my purposes here, I will try to show that street art often functions as a tool of this sort of anti-capitalist spatial secession in Berlin.

Hirt names six different forms of spatial secession, which often overlap with and work in tandem with one another. I want to focus on four of them that I think street art performs, or helps perform, in Berlin.

- Stylistic secession involves the disruption of the architectural ecology of a neighborhood with structures or features of the built environment that do not bear an aesthetic or functional relationship to their surroundings. As Hirt describes it, it “is the ‘masked ball’ of architectural styles … Affluent new suburban areas are especially keen on the aesthetic shock-and-awe effect. … Aesthetic judgment aside, however, the goal of much new architecture seems to be precisely disjuncture, secession and partition, temporal (from communist-era discipline) and spatial (from the public street).” 15Sonia Hirt (2012), Iron Curtains, Gates, Suburbs and Privatization of Space in the Post-Socialist City Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pp. 52-3. In Berlin, I argue, the aesthetic disjuncture and secession is from capitalist consumption of the street, not from communist-era discipline.

- Spatial seizure is the appropriation of public space for private use. “It can entail activities such as building permanent structures in formerly public spaces … [or] placing temporary structures in public squares or streets.”16Ibid., p. 51 Hirt interprets spatial seizure as part of the post-communist recommodification and privatization of space., but in Berlin this appropriation often has the opposite purpose.

- Spatial enclosure is, according to Hirt, “perhaps the most brutal way of seceding – by erecting formidable physical barriers and reinforcing them with multiple methods of restricting outsiders’ access.”17Ibid., p. 50. This traditionally includes literal barriers such as walls, gates, and fences, though I will argue that street art can create barriers that enclose space.

- Spatial exclusion is the effective limitation of general access to a space, not through material barriers but through mechanisms such as price, securitization, and memberships. I will argue that street art can serve as a mechanism of spatial exclusion, making clear who belongs in a space and who does not, and marking it out as a bounded territory.

I will discuss these mechanisms of spatial secession in turn.

Stylistic Secession

Hirt portrays stylist secession as an aggressive display of space as private property. But in Berlin, stylistic secession is used specifically to flag certain kinds of spaces as being separate from the capitalist landscape—as pointedly not available for commodification, and as intentionally disrupting and resisting the meaning of the gentrifying neighborhood around them.

The inside of the space is not private property in the traditional capitalist sense, but rather protected from the incursion of commodification and the capitalist gaze.

It is not difficult, in Berlin, to tell when you are walking past a ‘soli’ squat or hausprojekt run by spatial activists. These buildings practice extremely distinctive stylistic secession. They are works of art in their own right, and they are actively discontinuous with their surroundings. Decorated with dense layers of art and signage from top to bottom, one can spot these spaces from blocks away. Their aesthetics is pointedly decentralized, with chaotic layers, and rough DIY additions and structures, and jigged-together infrastructure. Their markings take many forms: apolitical art in many styles, often with pop culture references or a punk aesthetic; bright colors; and graffiti, signs, and posters announcing their anti-capitalist, pro-mobility, anti-surveillance, and anti-authoritarian politics; as well as their solidarity with other soli spaces in Berlin and with various far-left global political movements (see Figures 12, 13, and 14).

Figure 12: Rigaer 78, former squat and current hausprojekt and music venue in Fredrichshain. Photo by author, 2019.

Figure 13: K19, former squat and current women’s support center in Fredrichshain. Photo by author, 2019.

Figure 14: Liebig 34, a feminist anarchist queer squat for non-cis-men, currently fighting attempted eviction by a property developer. Photo by author, 2019.

Köpenicker Straße 137, or Køpi for short, is one of the most legendary of the Berlin squats, and one of the most powerful centers of anti-capitalist spatial activism in Berlin. Originally a traditional Altbau, its front quarter along with parts of its sides were bombed during World War II, leaving behind a three-sided building with an open instead of an enclosed courtyard in front. From the front you can see the stumps and outlines of half-bombed apartments that used to be along the sides. The remaining structure is, as Daniela Sandler put it, “monumental… aggressive, uncanny, intimidating.”18Daniela Sandler (2016), Counterpreservation: Architectural Decay in Berlin Since 1989. Cornell University Press, p. 65. Very shortly after the Wall came down, on February 23, 1990, anarchists and ‘autonomen’ from West Berlin crossed the former border, climbed the side of the fenced-off site, rappelled down into the courtyard, and staked their claim on the building by panting an enormous sign on the side reading “Køpi Bleibt.” Over the years, residents have added layer upon layer of art to the facade and the various inner spaces of the building.

Figure 15: Køpi 137 courtyard. Photos by author, with permission of residents, 2018.

All of these spaces use stylistic secession specifically to disrupt the gentrifying landscape around them and to aesthetically separate from that landscape, specifically for the purpose of marking themselves as disjoined from the colonizing spread of the capitalist commodification of space.

Spatial Seizure

Spatial seizure, or the intentional illegitimate appropriation of space, is inherent to the squatting tradition. Whereas Hirt focuses on the private seizure and commodification of public and unowned space, In Berlin, seizure is often designed to protect spaces from capitalist colonization through forms of intentionally anti-capitalist occupation. The ethic of Instandbesetzung, or reclaiming-and-repairing, is pervasive in the Berlin space activism community, and is the basis for many squatters’ claims to rights over the abandoned spaces they have occupied and remade, which they then use to fight developers who want to buy out the spaces.

Signage and art are used to seize unowned space and claim it as a territory that is not open for capitalist development. A vivid example is “Teepeeland,” a yurt and tent village on public land on the bank of the Spree, sheltered behind an abandoned ice factory, and settled by formerly homeless “autonomen” who wish to live without formal community. They have set up a small village that opts out of the capitalist economy, subsisting mostly on barter, communal labor, and dumpster diving. The founders of Teepeeland found even Berlin’s squatting scene to be overly dominated by young intellectuals with cultural capital, who they believed were insufficiently attentive to the needs of the truly poor. So far, the city has not tried to evict the residents of the village. If you find the path that leads to Teepeeland, you run into a rough (hard to photograph) hand-painted sign at its entrance that reads:

Welcome to Teepeeland

Please understand that this is a public and community area!

We ask you to RESPECT the PLACE and PEOPLE.

No sexism – no rassim – no aggression – no homophobic

This sign emphasizes both the public and inclusive character of the space, as well as that it has been occupied by specific people who belong there. What interests me about the space is how it is marked both as public rather than private property, and as an occupied place with a ‘people.’ This double meaning resists the normal neoliberal capitalist elision of residential space with privately owned space. Moreover, this territory has been carved out through art and signs rather than through any kind of physical barriers or legal interventions.

Figure 16: “Teepeeland.” Photo by author, 2018.

Spatial Enclosure

Squats and ‘hausprojekts’ in Berlin that are explicitly anti-capitalist often use fences, walls, and gates to enclose themselves. The residents of these spaces often do not want to be visible from the outside, because they do not want their alternative aesthetic ‘look’ to become part of the marketable tourist vista of the city, and hence to be commodified against their will, as Blu’s murals were. Art and signage are often used to phenomenologically enclose space by turning such barriers into what is experienced by outsiders as an impassible border.

The fence around Køpi, for instance, is not just visually impermeable, but also specifically designed to enhance the sense that Køpi is a territory of a specific sort, hostile to certain kinds of outsiders. Its marking with specific kinds of political signaling makes clear that it is a boundary around a space defined by its politics, not by private ownership. Although the fence is a material barrier, the gate is always open. Thus the fence works to keep people out through its aesthetic presentation, which creates an experience of territory that only belongs to a certain kind of person. The fence works phenomenologically to form a barrier between insiders and outsiders.

Figure 17: The fence around Køpi. Photos by author, 2018.

One form of anti-capitalist spatial enclosure practiced in Berlin is virtual: leftist spaces, and squats in particular, have had themselves blurred on Google Streets, to make themselves literally invisible to capitalist surveillance of the city. They show up visually as gaps in the landscape. This practice of opting out of inclusion in the virtual landscape is a form of spatial enclosure that operates entirely at the visual level, but is quite effective. It stops virtual tourists from even finding these spaces to start with. The blurring can also perhaps be read as a kind of stylistic secession–a visual way of disjoining from the surrounding landscape; but if so, this is a degenerate case of stylistic secession, since the ‘style’ is aggressive invisibility. The pointed invisibility of the art that actually adorns these buildings to curious online voyeurs signals that this art is part of a secession from the capitalist colonization of the city, and not a part of its marketable spectacle. Virtual spatial enclosure of leftist spaces through blurring also prevents the art on the face of these buildings from being monetized and consumed as data by Google. There is an irony built into the practice, however, since the presence of the blurred image is a clear guide for those who are attracted to the aesthetics of the squats, letting them know that there is something in that place worth seeing. Thus the virtual spatial enclosure may lead to more exposure in real life. This underscores the colonizing power of Google over space.

Figure 18: Google street views of the hauseprojekt Rigaer 78 and the squat Liebig 34, pictured in Figures 12 and 14 above.

Spatial Exclusion

Berliners use art as a technique of spatial exclusion to establish communal territories and keep out gentrifiers and others interested in commodifying their spaces. Political signage, signs that ban photography, and signs warning off racists, Nazis, and homophobes are used to create and mark the edges of spaces, making them unwelcoming to those who do not share the political orientation of those on the inside. This is so even while signs welcoming refugees, and opposing borders and bigotry, make the spaces inviting to other sorts of newcomers. Much street art on and around occupied spaces is used to create an aesthetics of intimidation, and even the implicit threat of violence, in order to ward off outsiders.

The built environment of Berlin lends itself to this kind of establishment of visual barriers. Most of the Altbau buildings have alleys leading to courtyards, and while these are physically open, it is not difficult to use art in order to produce the effect that these alleys are transitions to private spaces for insiders, beautiful but uninviting to those not initiated into the relevant community. While this there is no physically impassable barrier between the street and the courtyards, art in these passages creates a shift between the external and internal landscape. This kind of visual transition alters the experienced form of the space, setting up a phenomenologically tangible boundary around it.

Figure 19: Alleys into Hausprojekts in Prenzlauerberg. Photos by author, 2018.

Signage and art are vividly used as tools of spatial exclusion at Køpi. The building is mostly occluded from the outside, but the original “Køpi Bleibt” sign and the slogan “ACAB” (All Cops Are Bastards) are visible on the top of the building. Over the door to the courtyard, a red banner reads, “Wenn ihr uns nicht träumen lasst, essen wir euch nicht schlafen”, or “If you do not let us dream, we will not let you sleep,” thereby separating insiders from outsiders through the use of the first person plural and the second person. The door also features warnings against bigotry of all forms and bans photographs.19I received special permission to take photographs of the Køpi courtyard for research purposes, making my case at an anarchist house meeting. All these cues set up a phenomenological barrier between political insiders and outsiders, and appropriate and inappropriate users of the space.

Figure 20: The gate to Køpi. Photo by author, 2018.

Those who make it past the intimidating street face and through the open door are confronted by what can only be described as a giant “guard tiger” presiding over the courtyard. Next, one’s eye is drawn to the art and signs around it, including a large banner reading “against police brutality and G20 oppression.” All these works turn Køpi into a territory that is not for outsiders, and clearly mark who is an insider and who is an outsider to the space. But the inside is devoted to resisting capitalism, borders, exclusionary politics, and restrictions on mobility. The squat is run on anarchist principles of decision-making and opts out of the capitalist economy as much as possible. So the inside of the space is not private property in the traditional capitalist sense, but rather protected from the incursion of commodification and the capitalist gaze.

Figure 21: The Køpi courtyard. Photo by author with permission of residents, 2018.

Køpi is intimidating by design. Notably, almost every popular news piece on Køpi raises the specter of possible and feared violence.20For instance see Stephan Berg and Marcel Rosenbach (2008), “Die Autonomen und ihr ‘Plutonium’-Deal.” Der Spiegel; and (2007), “Berlin Commune Fights Property Developers.” Der Spiegel International. The occupants have managed to present themselves as capable of violence, as an aesthetic strategy, without ever needing to actually engage in it or even threaten it. In fact, the community has no documented history of violence whatsoever. Its activist methods are spatial seizure and occupation, material support for anarchist and anti-gentrification causes, and the implementation of non-hierarchical decision-making—not violence. While Køpi is committed fighting all forms of discrimination, barriers to mobility, and demographic exclusion, the look and shape of the space tells you immediately and unequivocally who is not welcome in the space: racists and right-wingers, but also anyone sympathetic with capitalism or neoliberalism, and, importantly, anyone who is just there to look. The space is not to be gawked at.

How can spatial activists in Berlin resist this subverting commodification of their cause, and how in particular can street art play a role in this resistance?

What interests me in all these cases of spatial secession is, first, how art is used to carve out space and create a territory and boundaries with clear insiders and outsiders, and it does so at the level of aesthetics and phenomenological experience rather than through material barriers or formal rules. Second, in Berlin, these aesthetic interventions are used to protect space from encroaching capitalist colonization and spatial commodification, rather than as performances of the capitalist privatization of space as personal property. Spatial secession works by creating spaces that have actively disjoined and protected themselves from the encroaching capitalist public landscape, but they are not privatized spaces. They are private in the sense of being hidden and territorialized, but they do not function as capitalist private property. These are spaces within which those committed to opting out of and resisting capitalism can collectively build other models of living. Their non-publicity can enable them to reach out as activists and offer protection to outsiders as they see fit, without being colonized.

I’ve tried to show that residents of Berlin use art to forge place identities that are distinct from those imposed by the state or by market forces. I’ve argued that, perhaps counterintuitively to some, distinctive forms of secession from public space, including certain forms of privacy that are not to be equated with private property, are key to resisting its capitalist commodification, rather than manifestations of it, in Berlin. In a city that is seen as ‘undervalued’ and highly ‘marketable’ by investors and developers, privacy and exclusion may be required to protect spaces from the encroaching capitalist consumption of space. Moreover, art and other forms of visual marking are central tools in producing and maintaining these anti-capitalist spaces.

Coda: The Paradox of Anti-Capitalist Place Marketing in Berlin

We have seen that street art is used in Berlin in multiple ways with different performative structures, in order to reshape space and territory and to establish boundaries, in ways that push back against the rapid capitalist consumption of the landscape. In an ironic twist, however, the dense, decentralized, layered and bottom-up look of Berlin, and the way that artists have shaped the form of spaces in unexpected and subversive ways, is part of the aesthetic that attracts tourists and new residents. We saw, for instance, how the street art aesthetic was commodified in Media Spree’s appropriation of Blu’s murals, and marketed to potential gentrifiers wanting to move into a ‘hip’ Berlin neighborhood. More generally, the aesthetics of alternative, leftist resistance and spatial activism, especially as embodied in street art, has in fact become one of Berlin’s main ‘selling points,’ and part of its place marketing. As we saw, real estate prices are escalating dramatically, and the city is becoming increasingly appealing to foreigners from around the world, including those from wealthy nations. But part of what attracts people to Berlin in particular is its DIY aesthetic, and its progressive, anti-capitalist political culture. The result, ironically and to the distress of many Berliners, is the commodification of this very aesthetic as part of a capitalist move towards gentrification.

The city is tolerant of street art and signage part precisely because it helps draw in tourist dollars and add to Berlin’s “branding.” Specialist in urban design Graeme Evans points out that Berlin’s official tolerance and even approval of uncommissioned street art is linked with its UNESCO designation as a ‘City of Design’ “and a growing cultural tourist destination, which is in part fueled by this urban image of street creativity.”21Graeme Evans (2016), in J. I. Ross (editor), Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art. Routledge, p. 175. More generally, Evans argues, street art has become a recognized engine of urban ‘regeneration’ and gentrification in many cities around the world. Indeed, encouraging street art is explicitly part of neoliberal place-marketing strategy in places like Bogota, Brooklyn, and Lisbon. It is difficult for artists who are trying to disrupt and claim commodified, marketized space not to accidentally become directly complicit in this commodification and marketization

Urban planning theorist Claire Colomb22Claire Colomb (2012), Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989. Routledge. has documented and analyzed this phenomenon in detail. She has tracked “The integration of subculture into mainstream marketing discourse” in Berlin.23Claire Colomb (2012), Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989. Routledge, p. 239 She writes, “From the early 2000s onward, the creative, unplanned, multifaceted, and dynamic diversity of such ‘temporary uses of space’ was gradually harnessed into urban development policies and city marketing campaigns.”24Claire Colomb (2012), Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989. Routledge, p. 238 She points out how alternative events and symbols in Berlin have been co-opted by the tourist industry and incorporated into place marketing materials such as tourist brochures. For example, the Love Parade was established by Berliners as an alternative queer pride event, specifically to push back against the capitalist commodification and pinkwashing of the “official” Berlin Pride Parade, but the cycle has iterated, and now the Love Parade is “officially marketed as part of the desire to present Berlin as a young, tolerant, and cosmopolitan city.”25Claire Colomb (2012), Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989. Routledge, p. 239 Much of what makes Berlin distinctive is thus being inexorably coopted by a commodified aesthetic of leftist politics and bottom-up space-claiming, particularly (but not only) as embodied in street art. At this point, it is often hard to tell, just from looking, when this aesthetic is ‘authentic’ and when it has become really just an aesthetic, overlaying a more conventional capitalist set of goals and arrangements. The marketing of alternative culture and its aesthetic has put squats and hauseprojekts in a bind. Alexander Vasudevan, who conducted an in-depth study of the history and ethnography of the Berlin squatting scene, comments, “Whilst the continued existence of alternative housing projects represented an opportunity to experiment with radical forms of shared living and working, it also reminded squatters that their survival stemmed, in no small part, from the cultural capital they conferred on an increasingly neo-liberal city.”26Alexander Vasudevan (2015), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin. John Wiley & Sons, p. 176

Unfortunately, the stylistic secession practiced by squats and hausprojekts seems especially easily co-opted, since these beautiful and unusual buildings are a major attraction for the city; they are, for instance, the focal points for many ‘alternative’ walking and cycling tours run by guides. Explicit anti-capitalist signage and messaging seems like it should be less easy to co-opt. But since everyone in Berlin is used to seeing anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian content exist side-by-side with trendy boutiques, high-end restaurants, and expensive housing, its potential for conveying genuinely transgressive or resistant messages is dampened. On Mainzerstraße in Fredrichshain, once the street that hosted the highest density of squat houses and the site of the biggest and most historic confrontation between squatters and police27Alexander Vasudevan (2015), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin. John Wiley & Sons., “fuck yuppie consumption” and “capitalism = fascism” graffiti comfortably adorns the fronts of yoga and pilates studios, a mead-themed gift shop, and craft beer pubs.

How can spatial activists in Berlin resist this subverting commodification of their cause, and how in particular can street art play a role in this resistance? Is street art in Berlin doomed to contribute to the very colonization of space it resists? Arguably, the kind of rough, not especially decorative tagging we see on the East Side Gallery might be among the least easily coopted and most effective interventions, precisely because it doesn’t look especially creative or attractive. We have also seen that art and graffiti can be used to establish territory and intimidating boundaries that genuinely discourage gawkers and outsiders from entering, and likewise to create an intimidating front that discourages would-be developers from forcing a confrontation with squatters and occupiers. To this extent, art does seem to be a legitimate, if delicate, weapon for spatial activists. I don’t think there is a settled or stable answer to the question of whether the commodification and colonization of the aesthetics of anti-capitalist resistance is inevitable. Apparently, Berliners are still finding ways to use aesthetic interventions in order to push back against the cooption of their own aesthetic.28I am grateful to the residents of Køpi for allowing me to take pictures and for talking to me in depth about the mission and workings of the space. I am grateful to Kathleen Smith and Eli Kukla-Manning for extensive conversations and comments on earlier drafts.