Andrew Anastasi is the editor and translator of The Weapon of Organization: Mario Tronti’s Political Revolution in Marxism (Common Notions, 2020). He is a member of the Viewpoint Magazine editorial collective and a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the City University of New York.

My first encounter with Tronti was an intense experience. His fifty-year-old writings resonated in a surprising way, and they offered new tools for thinking through problems that I was facing in my own workplace and organizing. Putting together this book has been an experiment, to see if that kind of effect could be multiplied by translating his ideas not only into a new language, but across time and space for new readers. To be sure, Tronti has been a reference point for activists and writers beyond Italy for decades, and his influence on Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Silvia Federici, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, and so many others has long been acknowledged.

For my part, I was interested in presenting more of Tronti’s own writing – not to pretend to furnish unmediated access to some authentic or true font of knowledge, but to encourage an appreciation of the unique rhythm of his thought. As I dug deeper, beyond the canonical texts, I began to appreciate how he responded to shifting relations not only between workers and capital – although, of course, these remain central – but also between and among grassroots militants, party leaders, capitalist fractions, and state managers.

This book is framed as much for contemporary activists and militants as it is for students of Marxist theory and Italian political history. We should always keep in mind that at the time when Tronti was composing the texts subsequently collected in Workers and Capital – now, at last, available in full English translation – he was engaged in a series of collective political experiments with different groups and publications. The Weapon of Organization tries to illuminate those concrete organizational activities which fuelled the development of operaismo.

These activities included kinds of political work that will be familiar to contemporary organizers and activists: producing and circulating newspapers and flyers, consolidating perspectives among comrades, producing new theory in relation fast-developing movements, reckoning with existing institutions while experimenting with new organizational forms, and more.

The collection draws from the essential work of Giuseppe Trotta and Fabio Milana, whose L’operaismo degli anni sessanta (Rome: DeriveApprodi, 2008) excavated a treasure trove of primary documents from the 1960s. I found myself drawn to texts by Tronti that speak to contemporary debates – on organization and the party-form, on the relationship between social democracy and communism – and I was also intrigued by work that was less polished, including private letters and talks given to comrades, because these forms can sometimes provide points of entry that are less intimidating for new readers. When paired with Workers and Capital, they also shed light on the practical dimensions (and ambitions) of Italian workerism.

For the most part, the organizational initiatives and experiments of the operaisti go unmentioned in Workers and Capital, even if the latter certainly bears their imprint. Take its table of contents: after an introduction, Workers and Capital lays out “hypotheses,” proceeds with an “experiment,” and thereafter presents a set of provisional “theses” (followed, in the second edition, by a postscript).

A new reader might be curious to know more about the “new type of political experiment” to which the middle part of the book refers. That experiment was key: it involved a leap from investigating how workers were struggling (and being quite impressed!) to trying to intervene within those struggles to foster their revolutionary growth. Many of the texts in The Weapon of Organization are commentaries on that political experiment itself – how it was going, what needed to change, what activists might try next, etc.

In the early 1960s, Tronti, Romano Alquati, Raniero Panzieri, and others laid out a series of provocative hypotheses in the pages of Quaderni Rossi which concerned forms of “invisible organization” in wildcat strikes, mechanisms of neo-capitalist development in postwar Italy, and state initiatives in “democratic planning.” A rather impatient group around Tronti, Alquati, and Negri wanted to dive into the project of building a network of militants who could carry this theory into the burgeoning working-class struggle and help to orient it. This meant writing not only in journals but experimenting with slogans, binding groups around their political perspective, and distributing leaflets, flyers, and newspapers to workers outside factory gates each morning and night.

Some of this history can be gleaned by reading Workers and Capital, and to be sure, the theoretical formulations found in that book are generally sharper and more concise. But the texts collected in The Weapon of Organization allow for a richer understanding of the period, and, like all B-sides, they bring to the fore otherwise obscure themes.

Reading them all together convinced me, for instance, that the capitalist state was more central to Tronti’s thinking during this period than is generally acknowledged. Already in the early 1960s, years before the flourishing of Marxist debates about the capitalist state, Tronti was paying close attention to competing fractions of the capitalist class, their uneven relations to different strata of state managers, and how working-class struggle frustrated the smooth implementation of reforms that might otherwise secure the longevity of capitalist society. In short, he developed a Marxist perspective in which the unity of the state and the capitalist class could not be taken as given.

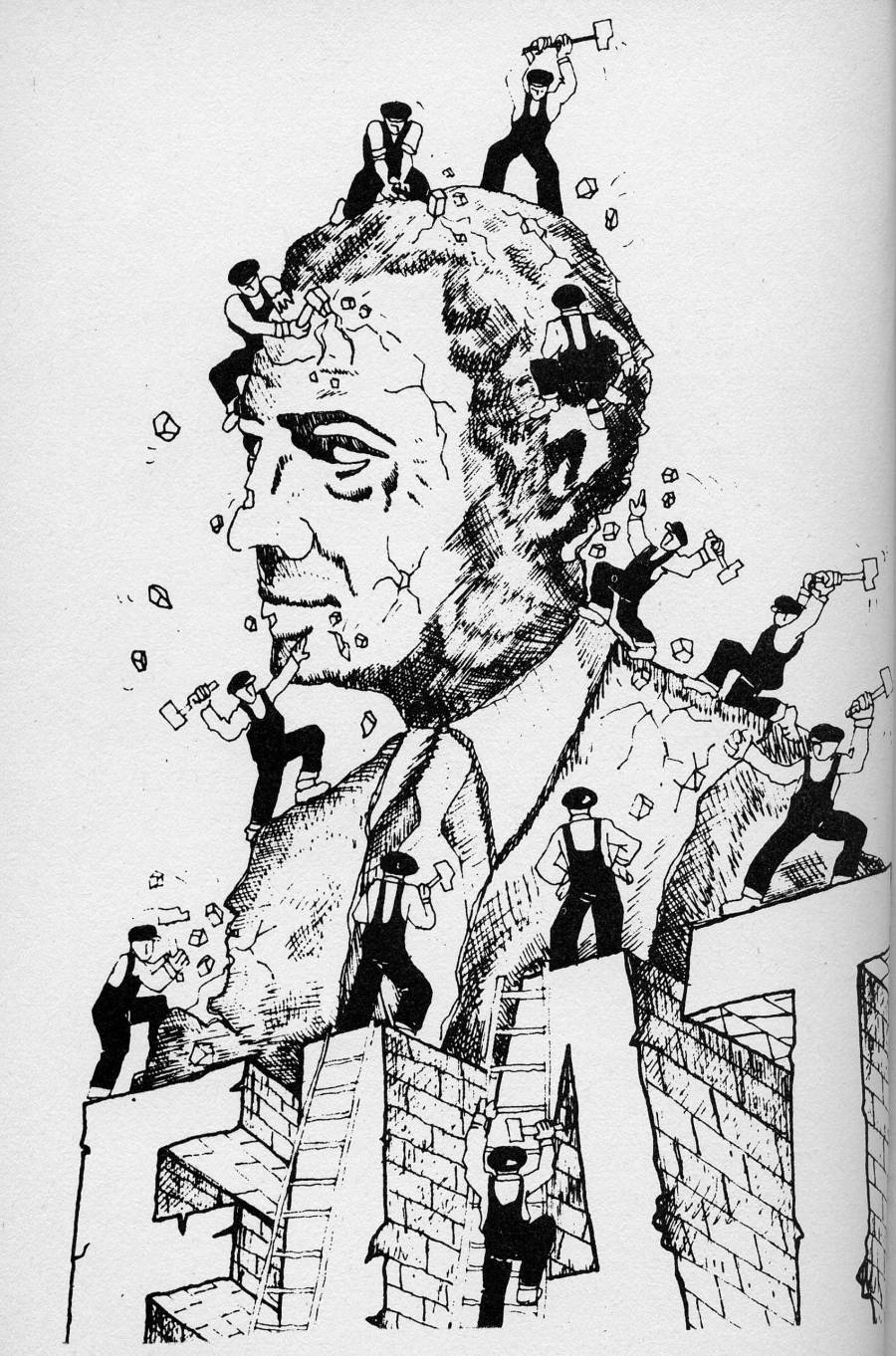

No question, the factory was absolutely central to Tronti’s thinking and practice throughout this period. One of his criticisms of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was how far removed it had become from class struggle inside the workplace, opting instead to pursue socialism via the parliamentary road. In his eyes the movement to smash the state must start out from workers organized at the point of production. But this did not lead to syndicalism. Continuing and expanding this movement required the production of a new, concrete unity, a re-articulation of the party to the class.

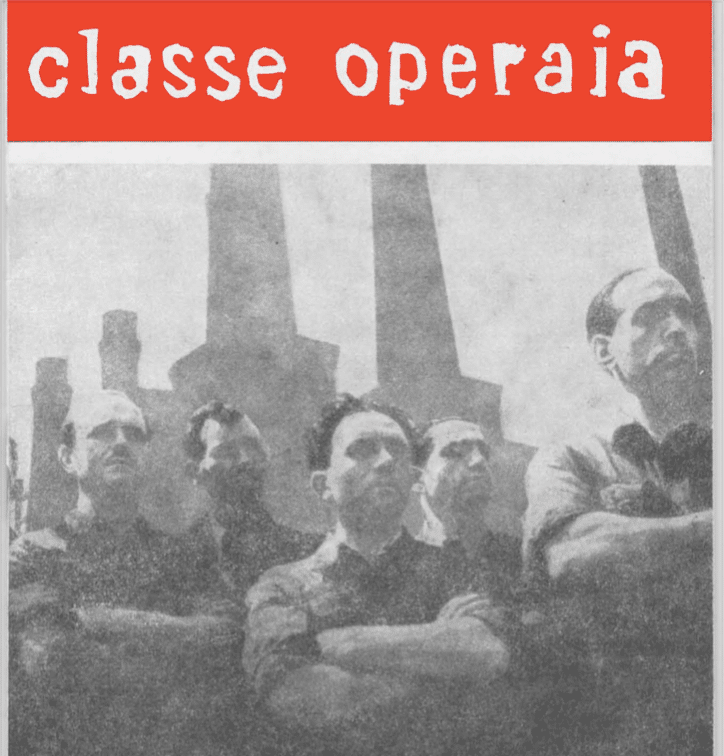

At the same time, looking toward “the party” did not mean abandoning workplace struggles for elections. On the contrary, Tronti’s project was crystallized in the slogan of “the party in the factory.” This phrase does not, to my knowledge, appear in Workers and Capital, but it was explored in an April 1965 speech and subsequent Classe Operaia editorial. “The party in the factory” did not signal bureaucrats coming in to dictate the terms of factory struggles – Tronti emphasized the need for a “workers’ control over the party” – instead it highlighted the need to develop an organ inside the factory that could “produce, accumulate, and reproduce” working-class strength on an extended scale.

By the time Tronti was making these arguments in the spring of 1965, he had determined that

Certainly Alquati remains the early operaista who did the most to advance the concept of class composition. But I agree, it is interesting to see it here, too, in Tronti’s writings of the early 1960s. In “The Strike at FIAT,” written in the summer of 1962 for Lelio Basso’s journal Problemi del socialismo, he pinpoints how capital reorganizes the production process in an attempt to decompose the unity achieved by workers, only for this same reorganization of production to also provide new opportunities for workers to recompose themselves into an even stronger political force – a class, understood in political terms. If Tronti was harshly critical of spontaneism, he was no more a fan of sociologism.

I think Tronti’s perspective during this period gels well with Elbaum’s. Take “The Copernican Revolution,” a speech which previews “Lenin in England” – although, as you have carefully illuminated in your own forthcoming work, the two also diverge in language and tone. There he argued that the “total refusal” of the workers:

can happen only when indeed this working class is not only a social mass, but a politically organized social mass, in other words, one that is politically functional to the point of actually expressing political organization in new forms, in forms that basically we do not yet know, that we still must discover.

There are several interesting elements in this passage. We can see Tronti’s openness to new forms of organization and his simultaneous insistence that this organization must be “political,” not only “social.” This resonates with his political conception of class as a form forged through struggle rather than resulting from sociological stratification, an insight which allows us to put his project into conversation with the likes of Nicos Poulantzas, Daniel Bensaïd, Alain Badiou, and others. (By the way, in terms of Tronti’s relevance to wider debates among Marxists, this same speech argues that “a bourgeois revolution as such has never existed,” tackling a problem explored more recently by Neil Davidson, Heide Gerstenberger, Charlie Post, and other writers with whom the readers of Spectre will be familiar.)

Returning to the political v. the social, it may not be immediately clear what politics, or political organization, means. How does politics happen, and what constitutes political organization? For Tronti politics cannot be a spontaneous expression of the workers’ objective social location, nor can it be a function of existing institutions like unions or parties. Instead, politics consists in experimental collective intervention into sites of ongoing struggle.

As he would write in “Marx, Labour-Power, Working Class,” the centerpiece of Workers & Capital: “the important thing is to be Marxists in a single, rough sense, namely as revolutionary militants on the working-class side.” Experiments need Marxist militants to carry them out, and these militants were to be partisans of the workerists’ viewpoint. It should be emphasized that this point of view was not plucked out of thin air but rooted in a concrete analysis of a concrete situation, in the research program and the workers’ inquiries of Quaderni Rossi.

So who were these Marxists in a “rough” [rozzo] sense? Who were these militants? In Tronti’s “Report at Piombino” from May of 1964, a few months into the Classe Operaia experiment, he reflected on this question:

To help advance the kind of active politics that we are proposing here means to apply oneself to the building up of a new type of political militant, one who explodes the traditional concept of the political organization in the party sense, the bureaucratic organization—one who reintroduces the question, in the most correct form possible, of a political organization that is indeed of a new type, completely different from those traditions.

This militant of a new type breaks from the dead weight of calcified tradition, in part, by taking guidance from the proposals Classe Operaia was making for a revolutionary movement, centered in the factories but extending to the state, where working-class strength is found in every moment of capitalist development, in fierce opposition to reformism of all stripes.

Classe Operaia was conceived of as a newspaper rather than a journal. In this the operaisti were well within the Leninist tradition – Lenin often spoke of how the newspaper provided a nascent form of organization for militants, who had to meet deadlines, figure out the newspaper’s production, coordinate its distribution, convince people to read it, etc.

For Tronti the newspaper was also special because it could mediate between Marxist theory and the workers on the shopfloor. At one point he refers to three “moments”:

- theory at a high level of abstraction;

- concrete political lines developed in the newspaper; and

- factory interventions, launched by networks of cadres, who were guided by and committed to the newspaper’s perspective.

Holding these three moments together as a concrete unity, not an immediate or reflective identity, but a unity that needs to be painstakingly built and continually maintained by Marxists – this for me is one of Tronti’s great contributions to political thought.

The texts in The Weapon of Organization chart this process, too, of producing and reproducing a concrete unity through newspaper work. Frequent publication could afford a tighter relationship between writing and movements on the ground, and operaisti worked on pamphlets, slogans, and rallying cries with and for workers. But completing the circuit was a challenge. Tronti was disappointed after the first year of the newspaper, thinking it had remained too abstractly theoretical, and too focused on history to the exclusion of providing “political tools for intervention into individual situations and opportunities.”

It still remained to build a network of cadres capable of translating the political line from the newspaper to the daily goings-on in the factory, and vice versa. Tronti was relentless in his self-critique: however elegant or correct their theoretical framework may be, it would not automatically manifest successful intervention into specific struggles.

Putting stock in developing a layer of political actors, a stratum of militants, the people who would show up to meetings, assiduously distribute leaflets, win over comrades to their point of view: emphasizing all of this did not mean valorizing charismatic leadership or bureaucracy, even if Tronti would later flirt with Weber’s writings. It was about committed work on behalf of the workers’ particular interest.

Ultimately this network was not built, at least not under the auspices of Classe Operaia, nor at the scale Tronti had in mind. Classe Operaia remained a formidable but ultimately small operation, which partly explained why Tronti refocused his efforts on the PCI, an institution which meanwhile had its own traditions of militancy (documented by Alquati as well as Danilo Montaldi, whose work remains untranslated). But Classe Operaia’s project was not merely aspirational. By April of 1964, for instance, they had circulated 4800 flyers to workers at Alfa Romeo and Pirelli, and 600 copies of the first two issues in Milan’s factories. According to a report given by Mauro Gobbini, workers were eagerly taking it up across departments, reading and debating the arguments inside.

Before the first issue of Classe Operaia appeared, we have notes attesting to Tronti’s interest in replacing the leadership of the workers’ movement with a new layer of working-class organizers. In “Noi operaisti,” the longer Italian edition of a 2008 essay edited and translated as “Our Operaismo,” Tronti wrote that he had always hoped Classe Operaia’s immersion in struggles would produce a group that could contest the leadership of the official workers’ movement. Through sustained political activity, he hoped to constitute a counter-leadership that could achieve some degree of hegemony among those on the Left who were not convinced by the PCI’s existing program. This stratum of leaders – built from initiatives within the factory, participating directly in struggles over work rather than in elections – would, he hoped, eventually take over the leadership of a thoroughly reorganized PCI.

By 1967 Tronti was stating this clearly. After the closure of Classe Operaia, he gave a talk later published under the title “Within and Against.” He had deployed this couplet before: since 1962 he had been writing of the need to root “the general struggle against the social system within the social relation of production” (my italics). In 1966 he spoke of seeing the working class “one time within capital, another time against capital,” with the unification of production and refusal providing the premise for a serious revolutionary rupture.

But only in 1967, when he begins to focus more closely on problems of political mediation, does he bring this logic to problems of the party and the state. At that point, he writes, “As the class is within and against capital, and as the party is within and against the state, so must one be within and against the party, such as it is,” broaching even the need to work “within and against” a social-democratic transformation of the workers’ movement.

We should keep in mind that this stance required collective commitment. In other words, to be in and against the reformist movement, the calcified political party, or the capitalist state was not a personal ethics of responsibility. Nor was it a matter of adjusting oneself to the sluggish pace of a long march through the institutions. In 1966 he had argued strenuously for work within the PCI precisely in order to prevent its rightward drift into coalition with the Socialist and Social-Democratic parties. Contesting the looming social-democratic solution to the problem of long-term capitalist stability was, in his eyes, a way of doing political justice to workers going on strike and the “massification” of their struggles.

So “within and against” was about establishing an autonomous political force, rooted in existing struggles at the point of production – where the working class is within and against capital – and working to achieve political dominance. What complicated the formula was that, while Tronti asserted the need “to make [the party] explode” and “smash the state machine,” he also wagered that a new organized political force could make use of the infrastructure, historic legacy, and mass purchase of the PCI. This was a political decision with consequences.

The Party certainly didn’t have a good name among all militants of the Left, and Tronti lost many comrades going this way. But he gained some, too. Party membership – not just votes for the PCI, but enrollment in the organization – grew by about 20% between 1968-1977 (after falling off a cliff post-1956). This is not to say these new conscripts adhered to his line. But it’s worth noting, whether this decision was right or wrong in the long term, that Tronti was not alone in finding this kind of work promising in the late 1960s.

We still hear “within and against” reverberating today. Labour Transformed in the UK has adopted “in and against” as their position toward the party, the state, and the trade unions. Working in and against the U.S. Democratic Party has been floated in discussions around the Democratic Socialists of America. Of course, entryism into a capitalist party like that of the Democrats in the United States, or a social-democratic party like Labour, requires a different set of considerations from those animating Tronti’s work around the Italian Communist Party of the 1960s. That project had been predicated on the PCI’s exclusion from government – it had only been part of the majority during the immediate postwar period of 1944–47. The U.S. Democrats and Labour, by contrast, have headed numerous governments, not to mention their role in defending and maintaining imperialism. The Democrats, if we want to focus on the U.S., are fundamentally a party of capital.

This is not to say the slogan cannot travel. But creatively stretching “within and against” to pertain to such different fields of play requires more than common-sense agreement that it seems generically reasonable to do what one can with the hand one is dealt. Certainly, many organizations and groups of militants interested in “within and against” politics are leaping beyond this.

I would just add that, if it is a question of maintaining fidelity to Tronti’s wager in 1967, a collective political subject might also rediscover the “strategy of refusal” animating working-class struggle in the 21st century, and it might articulate tactical work “within and against” a party or state to that larger revolutionary project. In the U.S. context, this could involve various kinds of extraparliamentary work, co-research among grassroots militants today, and a series of focused investigations: to account for autonomous, anti-state, anti-capitalist initiatives; to chart their political subsumption by strata of state managers over the past 50 or 100 years; to ascertain the role of various levels of the Democratic Party and of different capitalist strata in those projects; to unearth processes of anti-state, anti-capitalist subjectivation that may have emerged in relation to activities within the state; to look for antagonism percolating among state workers, whose ranks after all far outnumber elected officials; and so on.

Because Tronti’s conception of class is political, because his framework starts from the actuality of struggles, I think it remains provocative and useful for those seeking to understand and expand tenant struggles, working-class initiatives around health and education, and street rebellions. It’s plain to see that anti-racist struggles are a cauldron of working-class recomposition today.

If FIAT was a “nerve center” of Italian capitalism in the 1960s, it was not only because workers there manufactured automobiles, those most classic of Fordist commodities. It was also, crucially, because FIAT workers were “proud and menacing” – antagonistic toward their bosses and confidently going on the offensive. The same impetus today brings us to healthcare and education workers, to eviction defenders, to those engaged in direct actions against courts, ICE detention centers, and fossil fuel pipelines – and to the question of how organization may help these all add up to something more than the sum of their parts.