Reckoning with the Alma Mater

December 16, 2025

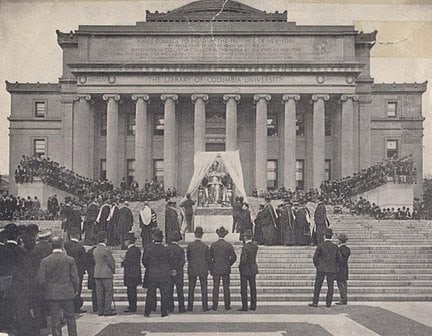

The Owl in Her Robes

Since 1903, Alma Mater has sat on the front steps of Columbia University’s Low Memorial Library. Daniel Chester French, the American sculptor who later created the monumental Statue of Abraham Lincoln (1920) in Washington DC, designed this bronze embodiment of institutional gravitas installed by Columbia during the height of the Gilded Age—a period defined by the consolidation of wealth, whiteness, and institutional power. French gilded the sculpture in gold leaf that has since worn away. She personifies the university: a laurel-crowned figure adorned in academic robes, seated with an air of certainty on a throne supported by lamps bearing the words Sapientia and Doctrina (wisdom and learning). She holds a scepter capped with wheat and a crown—symbols of civilization, order, and authority. A book rests open in her lap. In the folds of her robe, French hid a small owl, a classical emblem of knowledge. For more than a century, her steady gaze has presided over Low Plaza.

The Alma Mater statue originated as a gesture to commemorate members of New York’s elite. University trustees commissioned the sculpture through a donation from Harriette W. Goelet, who offered up $25,000 in memory of her late husband Robert Goelet (an 1860 graduate of Columbia who became a wealthy New York lawyer and real estate mogul). At a time when Columbia only admitted men—a policy that remained in place until 1983—the statue presented a figurative mother for an all-male student body. The statue looks out across the plaza toward the names of classical Greek thinkers, all men, engraved on the façade of Butler Library. Alma Mater’s representation of a woman stood as both muse and outlier on a male-dominated campus.

Photo Credit: T. C. Muller.

The statue’s central location and emblematic connection to the university have made it a focal point for campus activism. Students vandalized and bombed the statue during late 1960s uprisings. Decades later, during protests against the Iraq War, they repurposed it as a symbol of torture by hooding its head, mimicking the infamous images of detainee abuse at Abu Ghraib. Now, against the backdrop of the Zionist genocide in Gaza, Alma Mater has once again become a site of contestation. On September 3, 2024, students doused the statue in red paint after a call to action from the student-led Columbia University Apartheid Divest coalition, who demanded that the university divest from Israeli apartheid, call for a ceasefire, boycott Israeli academic institutions, and end the repression of pro-Palestine protesters.1Columbia University Apartheid Divest, “Columbia University Apartheid Divest: Who we are,” Columbia Spectator, November 14, 2023, https://www.columbiaspectator.com/opinion/2023/11/14/columbia-university-apartheid-divest-who-we-are/; Isa Farfan, “Columbia University’s ‘Alma Mater’ Sculpture Drenched in Red Paint,” Hyperallergic, September 4, 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/948132/columbia-university-alma-mater-sculpture-drenched-in-red-paint/. In the weeks that followed, students gathered at the statue’s feet to name the dead. Palestinian graduate student Mahmoud Khalil stood with others before Alma Mater and read aloud the names of Palestinians killed by Israel in Gaza during the previous year.

Several months later, with the complicity of Columbia’s administration, ICE agents detained Khalil (a permanent resident of the United States) and sent him to a facility in Jena, Louisiana. His wife, Dr. Noor Abdalla, gave birth to their child while Khalil remained behind bars for 104 days, unable to see or hold their newborn. His case starkly contrasts with the ideal of the university as a nurturing alma mater. While Columbia presents itself as a maternal figure to its students, it failed to offer Khalil protection when he sought help, not only obstructing Khalil’s efforts to be a caring parent but also sending in police to arrest students protesting the US-backed, Israeli genocide against Palestinians (many of whom are themselves children). These events shatter the fantasy of the campus as a protective and nurturing space, exposing Columbia’s willingness to sacrifice its own students to further its political and financial interests. Khalil’s case is far from resolved, and his future—like other students punished for their activism—remains in limbo.

In the institutional imaginary, those with outstanding student debt—over 42 million in the United States in 2025—are irresponsible fuckups in comparison with wealthy alumni donors, whose responsibility and generosity the university celebrates. Individualizing, paternalistic narratives obscure how the success of some relies on the exploitation of others. Universities also treat as disposable those who do not follow an idealized educational ascent in other ways—for example, through the expulsion and criminalization of Palestine solidarity protesters whose organizing threatens the colonial foundations of higher education.

The tension between the university’s self-image as a nurturing alma mater and its role as a colonial, capitalist apparatus that polices the boundaries of critical thought rests at the heart of higher education in the United States. The university often figures itself as a sanctuary, a space for free inquiry and intellectual growth, but this ideal collapses when students begin to think so clearly that they step out of cerebral contemplation into action. The university reveals its limits when students challenge the foundational violence of empire and capital.

In the midst of the ongoing genocide in Gaza, it may be tempting to hurl the charge of hypocrisy at faculty and administrators in the United States who call the police on student protests in the name of campus safety, academic freedom, and the university’s intellectual mission. However, framing these actions as merely hypocritical serves to uphold dominant institutions. Instead, the repressive actions of administrators and faculty are symptomatic of the foundational tensions within settler-established academic institutions. Rather than relying on moral outrage—as expressed in a statement like, “These university presidents are selling out their ideals by bowing to Trump”—our focus must shift toward an analysis of the underlying purpose of the university, its very social function. This approach both enables critiques of the university-as-it-is and opens space for educational projects that build alternative worlds. This dual move requires questioning our narratives about and attachments to academic institutions.

To understand what is happening to students like Khalil who have faced repression, we must interrogate the fantasy of the alma mater. What do we see when we look closely at our alma maters? Linking the abolitionist critiques of the family and the university, we argue that idealized conceptions of these institutions obscure political-economic and psychic processes at work within higher education. While the university presents itself as a nurturing institution, in reality it substitutes incessant assessment for genuine learning, operates as a speculative investment portfolio, and cloaks its extractive role within surrounding communities.

The University in the Mind

While the university exists as a physical campus, financial entity, and intellectual domain, unconscious fantasies and projections structure how students and alumni relate to educational institutions. Universities take shape as psychic objects or “organizations in the mind.”2David Armstrong, Organization in the Mind: Psychoanalysis, Group Relations and Organizational Consultancy, ed. Robert French (New York: Routledge, 2018), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429478079. Each person perceives their structure and functioning in a different way. Exploring these mental images of what the university is and how it works reveals how these internalized representations shape the dynamics of academic life.

The Latin words alma mater mean “nourishing mother,” and alumna translates to a “nursling” metaphorically suckled and nourished by an institution.3Julia Cresswell, Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 12, https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780198868750.001.0001. This etymology suggests an understanding of the university as a family—a transitional space between one’s family of origin and projected future family. Events such as “homecoming” games indicate a sense of the university as an abode. This protective home allegedly facilitates the student’s ascension up a romantic educational ladder—from kindergarten through the grade levels to higher education and beyond—reinforcing the university’s role in a Bildungsroman of individual growth, upward mobility, and security. The alma mater mediates the transition from dependence to independence, adolescence to adulthood, and immaturity to maturity. An emotional investment—rooted in the university-as-family—helps explain the strength of alumni networks, particularly at elite institutions.

The fantasy of the university as a nurturing home does not end at graduation but extends into the future as a subindustry of alumni engagement professionals strategically cultivate the loyalties essential for fundraising. Alumni associate themselves with their alma mater through branded clothing, bumper stickers, and alum-specific credit cards. This psychic investment materializes in the form of alumni donations, which allow graduates to project their continued ascent beyond the degree itself. By contributing financially, alumni symbolically reaffirm their attachment to the campus through the inscription of their names on buildings, rooms, benches, and trees. The figure of the alum continues this vertical educational ascent—a secularized form of older, religious imaginaries of spiritual elevation and transcendence that offer solace amid earthly precarity. Alumni magazines, with their donor honor rolls, circulate and legitimize these success narratives. The campus becomes a site for alumni to perform their rising selves.

The intertwined fantasies of the nurturing campus and the ascendant alum work together to uphold the ideological scaffolding of higher education and its economic infrastructure. Alumni donations make up a relatively small percentage of university budgets—$12.9 billion in total alumni donations to US universities in the 2023–24 fiscal year, which was 2.1 percent of colleges’ total expenditures.4Natalie Schwartz, “Charitable Giving to Colleges Jumped 3% in FY 2024,” Higher Ed Dive, March 20, 2025, https://www.highereddive.com/news/charitable-giving-colleges-fy-2024-case/743015/. Yet, the emotional attachments of the familial fantasy magnify the importance of alumni donations for universities’ operations and, conversely, obscure the greater financial flows to universities from more politically contentious sources. For example, at Columbia, the postdoc union compelled the administration to disclose the institution’s finances, exposing investments in both a gentrifying real estate empire in Harlem and companies profiting from Israel’s apartheid, genocide, and occupation.5 Financial Analysis of Columbia University – Howard Bunsis,” YouTube video, 1:30:32, posted by “Columbia Postdoctoral Workers UAW 4100,” May 2, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoF-w8tPGXw&t=1s. For more on Columbia’s role in gentrifying Harlem as well as on other universities’ extractive relationships to cities, see Davarian Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities are Plundering Our Cities (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021). Alumni can imagine their donations as “supporting the Columbia family,” allowing the university to divert their attention from these messier sources of wealth.

Institutions treat those who deviate from the familial fantasy’s romantic educational expectations as failures, debtors, and dropouts. Institutional prestige magnifies personal honor and conversely intensifies the shamefulness of these devalued figures. In the institutional imaginary, those with outstanding student debt—over 42 million in the United States in 2025—are irresponsible fuckups in comparison with wealthy alumni donors, whose responsibility and generosity the university celebrates. Individualizing, paternalistic narratives obscure how the success of some relies on the exploitation of others. Universities also treat as disposable those who do not follow an idealized educational ascent in other ways—for example, through the expulsion and criminalization of Palestine solidarity protesters whose organizing threatens the colonial foundations of higher education.

The metaphor of the university as a familial home presents the institution as benevolent and students as dependent children who should be loyal and grateful. This framing depoliticizes and naturalizes the university, suppressing questions about the institution’s functions and allegiances. It obscures conflict by portraying the university as timeless, unified, and stable. It allows administrators and faculty to justify repressive decisions through the fantasy of “the campus” as a bounded space where students require paternalistic protection, which Samuel P. Catlin describes.6 Samuel P. Catlin, “The Campus Does Not Exist: How Campus War is Made,” Parapraxis Magazine, July 2024, https://www.parapraxismagazine.com/articles/the-campus-does-not-exist.

Just as feminists have opened a horizon of collective care and solidarity that addresses both the needs for care ceded to the family and those abandoned beyond it, we envision possibilities for generative, collaborative, and life-giving study beyond the paternalism and sadomasochism of the university.

To loosen the family metaphor’s grip, we can examine its historical origins. The term alumnus came into use in the English language in the 1640s. The founders of the early American colleges implemented a “collegiate way of life”—imported from English institutions such as those at Cambridge and Oxford—that included a rural setting and dormitories with faculty supervision.7 Frederick Rudolph, The American College & University: A History (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 96, https://doi.org/10.1353/book11948. Alumni of Harvard University, the oldest operating university in the United States, had begun returning for graduation ceremonies by 1643.8A. Westley Rowland, Handbook of Institutional Advancement (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1986), 374. Alumni traditions took on a more formal institutionalized form in 1792 at Yale University with the custom of each graduating class appointing an alumni secretary. Graduates formed the first alumni association at Williams College in 1821. Alumni associations spread to other colleges with their purposes ranging “from keeping undergraduate memories fresh to keeping intellectual interest alive, from enticing student patronage to alma mater to soliciting supporting funding for her.”9John S. Brubacher and Willis Rudy, Higher Education in Transition: A History of American Colleges and Universities, 1636-1976 (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), 364. The history of alumni societies are rooted in exclusionary institutions that reproduce elite social networks—a history that complicates understanding the university as a welcoming family. The dependence of universities on enslaved labor and the plundering of Native peoples’ lands and lives—the dirty family secrets of many institutions—are hidden in the shadow of their familial imaginary.10Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013); Sharon Stein, Unsettling the University: Confronting the Colonial Foundations of US Higher Education (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022), https://doi.org/10.56021/9781421445052.

In contrast with the nurturing maternal image evoked by alma mater, the in loco parentis legal doctrine emphasized the disciplinary, regulatory, and patriarchal aspect of the family imaginary.11Christopher P. Loss, Between Citizens and the State: The Politics of American Higher Education in the 20th Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 36-37, https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691148274.001.0001. The legal doctrine emerged in response to student resistance to college rules enforcing white, patriarchal family norms—such as dress codes, curfews, alcohol bans, and sexual regulation. Administrators enforced these regulations most aggressively on women and students of color, whose involvement in civil rights movements they dismissed as “infantile.”12Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 230–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1qft0n6. The student movements of the long 1960s rebelled, in part, against the regulations of in loco parentis. During this period, the student left challenged the Fordist family’s norms across the university, seeking greater inclusion through affirmative action as well as institutional changes such as the creation of women’s health centers and new programs in women’s, Black, and ethnic studies.13Cooper, Family Values, 231.

These liberatory student movements innovated another metaphor, the university-as-factory, that helps to defamiliarize higher education. The factory metaphor emerged during the student struggles of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States, France, Italy, and other contexts. Berkeley student leader Mario Savio likened the university to a factory or firm that treats students as raw material.14Robert Cohen, Freedom’s Orator: Mario Savio and the Radical Legacy of the 1960s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 188, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195182934.001.0001. This metaphor laid bare the bureaucratic and economic structures of higher education and became a rallying point for resistance. In his 1964 sit-in address at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Hall, Savio called for civil disobedience to disrupt the university-as-machine, urging students to physically halt its operation. More recently, projects like the Edu-Factory Collective have emerged.15Edu-factory Collective, Toward a Global Autonomous University (New York: Autonomedia, 2009). Students have also invoked the factory metaphor to protest austerity, rising tuition, and administrative overreach, as during a building occupation at Middlesex University or the occupations at the University of California campuses during the 2009–10 academic year. Slogans like “The university is a factory. Strike! Occupy!” and references to students powering the “diploma factory” reflect a broader effort to illuminate the commodification of education.16Jonathan Wolff, “Why Is Middlesex University Philosophy Department Closing?,” Guardian, May 17, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2010/may/17/philosophy-closure-middlesex-university; Research and Destroy, “Communiqué from an Absent Future,” We Want Everything, September 24, 2009, https://wewanteverything.wordpress.com/2009/09/24/communique-from-an-absent-future/.

The metaphor of the university as a factory reframes higher education as a site of labor and production. This opens up avenues for critical reflection about the university as a workplace that centralizes authority in a managerial elite. The university-as-factory foregrounds the conflicts within the university and emphasizes struggle and collective agency. It also gestures toward the possibility of resistance through student strikes, grading strikes, and debt refusal. It suggests using collective action to halt, seize, and reconfigure the means of generating knowledge.

While some metaphors about the university bury tensions, others highlight them. Fantasies about the university can create an appearance of coherence that conceals its contested nature. Who speaks for an institution? Who is excluded from it? How are its boundaries drawn and maintained?

Who the University Serves

The sequence of events that has unfolded over the 2023–24 and 2024–25 academic years has unveiled much about higher education as a sector. Israel—with money, bombs, and a thumbs up from the United States—destroyed every university in Gaza. Liberals oversaw this catastrophic violence before passing the baton to fascist reactionaries. As students, staff, and faculty called for the divestment of institutional endowments from weapons manufacturers and the state of Israel, many universities revoked their professed commitments to free speech and academic freedom. Police assaulted students and charged them with trespassing on their own campuses. Public safety officers sat back as fascist goon squads beat up or kidnapped students.

While allegedly places for intellectual inquiry and discussion, many colleges repressed their students’ challenge to an unfolding genocide. These whiplash-like struggles can be confusing for anyone connected to universities, whether as a student, worker, parent, or alum. Under the banner of safety, universities have revived the in loco parentis doctrine in neoliberal form, adopting risk-management practices that—in shielding institutions from lawsuits—ultimately suppress students in the name of protecting them.17Cooper, Family Values, 253–55. These events prompt the question: what are these institutions actually about?

Here, we situate an abolitionist approach to universities in relation to the framework of family abolition, a linkage that can help free desires for collective studying from institutions that capture, hinder, and betray them.18Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (New York: Verso Books, 2022); M. E. O’Brien, Family Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of Care (London: Pluto Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.3508398; Abigail Boggs et al., “Abolitionist University Studies: An Invitation,” Abolition University, 2019, https://abolition.university/invitation/; Eli Meyerhoff, Beyond Education: Radical Studying for Another World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvpb3vm2. The ideology of the nuclear family frames it as a central site of safety, belonging, and care, while the university relies on its ideological claim to be the sole locus for meaningful and rigorous learning. Colleges are not actually good places to study. Their institutional norms transform the learning process into a competitive and alienating experience. Universities privatize, isolate, and instrumentalize learning, rendering it a paid service rather than a curiosity-driven process that unfolds over the course of one’s life. University abolition involves liberating study from institutions that betray the joy of collective investigation, research, and conversation. Just as feminists have opened a horizon of collective care and solidarity that addresses both the needs for care ceded to the family and those abandoned beyond it, we envision possibilities for generative, collaborative, and life-giving study beyond the paternalism and sadomasochism of the university.

The best kind of education teaches us how to shift from being passive spectators to active participants in the social world. Rather than living accorded to a prescripted Bildungsroman, we can learn how to enter the plot and redirect it. Instead of abandoning the terrain of higher education as a lost cause or being nostalgic for its golden age, we can intervene and actively transform these spaces.

This broader reimagining leads us to the past, where the role of alumni becomes key to understanding educational history. As alumni donations expanded in the nineteenth century, graduates sought greater control, which produced an ongoing tension with faculty and students over the purpose and direction of academic institutions. Following the Morrill Land Grant Act (1862) and the Emancipation Proclamation (1863), land-grant universities emerged to generate new forms of capital accumulation after the end of slavery, namely profiting from Indigenous dispossession, absorbing surplus labor, and reproducing class hierarchies. Universities also developed new sciences—of agriculture, mining, eugenics, race, and sex—to sustain accumulation and extraction.19Boggs et al., “Abolitionist University Studies”; Abigail Boggs et al., “Marx, Critique, and Abolition: Higher Education as Infrastructure” in The Palgrave International Handbook of Marxism and Education (London: Palgrave, 2023): 509–35, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37252-0, available at https://www.academia.edu/108991210/Marx_Critique_and_Abolition_Higher_Education_as_Infrastructure. Alumni movements arose in this context, such as Harvard’s 1865 act granting alumni power to elect its Board of Overseers. This repressive use of alumni power continues today through the influence of figures like Bill Ackman, who have pressured administrators to repress pro-Palestine activism.

Photo Credit: Wm3214 via Wikimedia Commons

Alumni associations at settler institutions developed alongside Indian and Black boarding and industrial schools. Settler universities cultivated particular students’ transition into white, heteropatriarchal adulthood, while boarding and industrial schools broke down Indigenous and Black communal relations to both the land and to the extended family structures more typical of these communities.20Joel Pfister, Individuality Incorporated: Indians and the Multicultural Modern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jhxs. Alumni societies replaced such communal ties with an institutionally mediated sense of belonging. Taking in these longer historical arcs reframes narratives about the alleged “crisis” within higher education and brings the core function of these institutions into view.21Abigail Boggs and Nick Mitchell, “Critical University Studies and the Crisis Consensus,” Feminist Studies 44, no. 2 (2018): 432–63, https://doi.org/10.15767/feministstudies.44.2.0432.Recognizing this is not about casting blame from a distance, but about acknowledging how one is implicated in these dynamics.

Abolitionist critiques are more important now than ever—for refusing liberal nostalgia for a golden age, post-1945 university and for transforming education into a liberatory process. We reject the common liberal inclination to postpone criticism of the university as it threatens a united front against the right’s attacks on higher education. Ascendant fascist movements calling for a reinvigoration of white supremacy, patriarchy, and xenophobia see universities as enemies to this reactionary strategy. While the right seeks to dismantle the university’s commitment to critical thinking, left abolitionists take that commitment seriously, using critique to understand the oppressive features of the university and to confront the parts of ourselves that remain invested in and identified with these institutions. Liberals and reactionaries ultimately both uphold a racial-capitalist order, while we seek to make space for those who imagine and fight for a future beyond capitalism. Investigating the alma mater/alumni relation helps open the university as a terrain of struggle and a place to assert alternative visions for the world.

Looking Askance

The university relies on a veneer of coherence and competence, which functions as a type of camouflage. At the core of higher education is a desire for achievement and expertise, yet intellectual life is an ongoing process that can be neither mastered nor finished. In contrast to the university’s phallic accumulation of publications and prestige, the actual experience of learning does not conform to linear measurement. The learning process is often more subtle and indeterminate than universities can name or tolerate. Staying loyal to intellectual life involves stepping back from academia’s misrecognitions and fantasies of it.

What counts as a “good” education? To defamiliarize is to step back from the familiar. Sometimes the things closest to us remain invisible. What we are familiar with we cease to see. You can graduate from a college and realize that you have no clue what sort of school you attended. It takes developing a particular type of eye to see the thing in front of us; to witness the character of the places where we find ourselves; to look with crushing specificity. Defamiliarization is a process of learning to see the contingency of what is around us and the possibility that it could be otherwise.

Beyond earning degrees, we envision a different mode of study that reclaims learning, inquiry, and critical thinking from these institutions. We distinguish between the standard view of education as culminating in one’s graduation from a particular college and the view of education as developing capacities for lifelong, intellectual curiosity and courageous study unafraid of its findings. Traditional education often fails to teach us how to show up for social movements, organize with our coworkers and neighbors, and find political leverage. This kind of study is vital for anyone committed to transforming the world and can be found within unions, social movements, and other organizing spaces.

Everyone’s alma mater deserves a probing, second glance. We understand colleges as contested sites. In a dialectical process, colleges are continually shaped from above and from below. Reckoning with the dynamics that underpin higher education is integral to the process of disidentifying with the university as it currently exists and grabbing the lamps of Sapientia and Doctrina (wisdom and learning) from the alma mater.

The best kind of education teaches us how to shift from being passive spectators to active participants in the social world. Rather than living accorded to a prescripted Bildungsroman, we can learn how to enter the plot and redirect it. Instead of abandoning the terrain of higher education as a lost cause or being nostalgic for its golden age, we can intervene and actively transform these spaces.

While alumni engagement usually refers to fundraising campaigns and nostalgic reunions, we foreground the current roles and potential power of alumni. We see such potentials, for example, in the “alumni for Palestine” groups that have sprouted up on numerous campuses. We are also inspired by the radical studying in projects such as the W.E.B. Du Bois Movement School for Abolition & Reconstruction, Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning, and the many people’s universities that emerged in the Gaza solidarity encampments.

Returning to the Alma Mater statue on Columbia’s campus, we can focus our attention on the owl that French tucked discreetly into her robes—small, almost hidden, but unmistakable. Historically, the owl has been a metaphor for the mind’s ability to see in the dark. Drawing from this imagery, taking stock of our alma maters becomes an act of night vision—of perceiving what is obscured. We come to see the university as a deeply dysfunctional parent who cannot understand us, no matter how much we might want them to. As the fantasies built around these institutions begin to unravel, it is time for the owl to take flight. This departure is less physical than psychic and political—a graduation and a release from the myths that give the university its parental role. As we begin to fly, the importance of recognizing other owls becomes clear. Study and struggle are relational projects, shaped by how we treat each other. What becomes possible depends on how we show up as friends and comrades—that is, on how we care for the fragile bonds that comprise relationships and movements.