What Are We Waiting For?

Part 1: Socialist Reflections on the Next Economic Crisis

August 5, 2025

This two-part essay draws upon crisis theory and the history of economic crises to reflect on the current turbulence and the next economic crisis. The second part can be found here.1Ståle Holgersen, “What Are We Waiting For? Part Two: Socialist Reflections on the Next Economic Crisis,” Spectre, August 8, 2025, http://doi.org/10.63478/2QEB2J49.

Given the centrality of economic crises to capitalism over the last two hundred years and the time intellectuals have spent trying to understand them, it is strange how little we know about the next one.

To navigate the 2020s is to steer through tempests and shocks. It is tempting then to simply declare everything a crisis. The popular term polycrisis serves this impulse: it is a concept broad enough to include almost anything the speaker considers bad as a “crisis.” But when reality is storming, we need an analytical framework that clarifies rather than obscures. This two-part essay draws upon crisis theory and the history of economic crises to reflect on the current turbulence and the next economic crisis. The first part of the essay begins by drawing on the work of Daniel Bensaïd and Bob Jessop to reconceptualize crises as societal paroxysms—highlighting the role crises play both as disruptions and transformative reconsolidations of the capitalist order. From this starting point, the remainder of Part One explores how we might understand economic crises in the 2020s and the near future.

Some weaknesses in current crisis discourse stem from how history is used (often unconsciously), others from conceptual confusion. Regarding history, I argue that much of our thinking remains anchored in the twentieth century, even though we are already well into the twenty-first. Conceptually, a major challenge is that many discussions of crisis proceed without ever defining the term. This makes it difficult—if not impossible—to distinguish between real crisis and pseudocrisis, a distinction that is vital in a decade marked precisely as a tangle of both real and manufactured emergencies.

The second part of the essay will ask how socialists should prepare for the next crisis. Rather than trying to predict the exact time and location of the next economic crash or propose a readymade program, the first part of this essay offers general reflections on the nature of the coming crisis, and the second part outlines how we might respond.

Crisis as Social Paroxysm

That economic crises are complex phenomena should not surprise us. They come out of an “anarchic” overall system governed by the law of value. They are a result of numerous ongoing processes (some much more important than others), they vary over space (for example, economic crises in the capitalist core often have very different implications than those elsewhere), and they involve both conscious and unconscious actions. The specifics of the next crisis will also depend on human actions yet to be determined between now and when it erupts. No wonder they are hard to predict.

In modern economic crises, two equally important processes always play out: first, they emerge from underlying processes and structures within capitalism; then, they serve as events and mechanisms through which capitalism is reproduced. Focusing on how capitalism produces crisis presents the system as brittle, fragile, and weak. But if we highlight how crises are resolved and capitalism is reproduced through them, it becomes clear how flexible, viable, and adaptable capitalism actually is.2Through understanding how crises are produced, we can criticize liberals who will never acknowledge that capitalism systematically produces crises. From acknowledging how capitalism is reproduced because of—and not despite—crises, we can challenge Marxists who think the next crisis is the end of capitalism (see for example. Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015). A comprehensive analysis of crises under capitalism must necessarily incorporate both perspectives.

Crises are complex by nature. Inspired by the French Marxist Daniel Bensaïd, we can view crises as antagonisms that erupt into paroxysms—that is, sudden outbreaks of a known disease. Bob Jessop’s work on the symptomatology of crises points in a similar direction. Crises are always both events (symptoms) and underlying processes or structures.3 Daniel Bensaid, “The Time of Crises (and Cherries),” Historical Materialism 24 no. 4 (2016): 9-35, https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-12341491; Bob Jessop, “The Symptomatology of Crises, Reading Crises and Learning from Them: Some Critical Realist Reflections,” Journal of Critical Realism 14 no. 3 (2015): 250, https://doi.org/10.1179/1572513815Y.0000000001. To understand crisis, we must analyze both the general laws of motion of capital and the history of capitalism—which is, according to Ernest Mandel, one of the “most complex problems of Marxists theory.” Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism, (London: Verso, 1978), 13. This means they exist on multiple levels, oscillating between surface phenomena and underlying processes.

In Against the Crisis, I argue that crises are societal paroxysms and propose the following definition: modern crises are turning points necessarily based on three core elements. First, they are events that emerge relatively quickly; second, they are embedded in underlying structures or processes; and third, they have negative effects on people or nature. Each of these distinguishing criteria is essential. Without the first, the concept includes permanent problems. Without the second, the concept would include coincidences, accidents, or events of random chance. And excluding the third criteria leads to the counterintuitive conclusion that positive occurrences are crises.4Ståle Holgersen, Against the Crisis (London: Verso, 2024).

That crises are societal paroxysms means that they are always temporally and spatially delimited and they must necessarily be located in something and arise out of something.5Jared Diamond is mistaken when he suggests that crises might arise from nothing. Similarly, the Danish anthropologist Henrik Vigh is wrong to argue that crises should be seen as permanent phenomena). Vigh’s definition of crisis as “poverty and distress” and equation of noncrisis with “balance, peace and prosperity” conflates crises with permanent phenomena and makes the concept useless. Poverty is poverty; crisis is crisis. While a crisis may exacerbate poverty, the two are not synonymous. There are no permanent crises. Jared Diamond, Upheaval (London: Penguin, 2020); Henrik Vigh, “Crisis and chronicity: anthropological perspectives on continuous conflict and decline,” Ethnos, Journal of Anthropology, 73.1 (2008): 5–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840801927509. In other words, crises under capitalism both shake and stabilize the system; they appear as weaknesses but are in fact integral strengths of capitalism. They serve to both transform and consolidate. Capitalism requires turbulence in order to survive. While crises pass as events, the underlying processes that caused them remain intact and ensure their recurrence.

While broad, the definition of crises as societal paroxysms has limits: not everything is a crisis and we are not always in crisis. Wars, poverty, or terrorism, for example, are not inherently crises, but can indeed be influenced or shaped by crises. By insisting on making some distinctions, we can also discuss which phenomena recur as crises or which are more permanent under capitalism.

Some situations may simply appear to be crises: they are pseudocrises. A pseudocrisis can be used by powerholders in similar ways as real crises, but lack the second element of the above definition: they do not come out of underlying structure or processes. In The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein showed how the International Monetary Fund could fabricate crisislike situations to discipline strongwilled countries.6Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (London: Penguin, 2007), 326. Political and economic rulers may also exploit existing turbulence, manufacturing a heightened sense of urgency to advance their own interests. Pseudocrises mimic the appearance of real crises, but are not embedded in actual underlying conditions. In our present moment, distinguishing between real and pseudocrises becomes increasingly important.

In our present moment, distinguishing between real and pseudocrises becomes increasingly important.

When we examine the history of crisis (and crisis theory), we see how people repeatedly make general claims about the nature of crisis that reflect their own immediate situation. Between the two world wars, the left focused on working class immiseration, which was reflected in underconsumption theories of crisis.7For overviews of the history of Marxist economic crisis theories, see for example Anwar Shaikh, “An Introduction to the History of Crisis Theories,” in U.S. Capitalism in Crisis, ed. Union for Radical Political Economics, (New York: Union for Radical Political Economics, 1978), 219–40; Simon Clarke, Marx’s Theory of Crisis (London: St Martin’s, 1994). During the 1970s, leftists turned their attention toward the strength of the working class, giving rise to crisis theories such as the profit squeeze and broader frameworks like Italian operaismo. These arguments suggested that working class agency and power were the key drivers of capitalist development and crisis. Today, after decades of harassment, many ignore the role of the working class altogether by shifting the focus to capital only, or perhaps “financialization.” Amid crises, it is an epistemic challenge to learn from shocks without overemphasizing or overlooking the most pressing concerns of the moment. But before looking forward to the 2020s, it is worth taking a brief look back at history.

History as a bewildering teacher

The young Karl Marx was preparing for capitalism’s downfall as soon as he saw signs of crisis on the horizon. “Physically, the crisis,” Friedrich Engels famously wrote in 1857, “will do me as much good as a bathe in the sea,” and “now it’s a case of do or die.”8Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (Mansfield: Martino Publishing, 2013), 296; Friedrich Engels, “Engels to Marx, Manchester, 4 August 1856,” reprinted in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, vol. 40 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, e-book, 2010). See also Sven-Eric Liedman, A World to Win: The Life and Works of Karl Marx (London: Verso, 2018), chap. 14; Peter D. Thomas and Geert Reuten, “Crisis and the Rate of Profit in Marx’s Laboratory,” in Riccardo Bellofiore, Guido Starosta and Peter D. Thomas (eds.), Marx’s Laboratory: Critical Interpretations of the Grundrisse (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 312, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004252592_016. It was either revolution or death. But the crisis of 1857 passed, as economic crises do, and was followed by a prolonged economic boom.

One reason Marx and Engels were so naïvely optimistic about the next economic crises was that they were misguided by history. The “defensive reading” of crisis developed in the seventeenth century was replaced in the eighteenth century by an “offensive reading” associated with thinkers like Rousseau and Thomas Paine, where one did not seek to avoid or retreat from crises. Instead, crises were seen as catalysts for historical progress.9Brian Milstein, “Thinking Politically about Crisis: A Pragmatist Perspective,” European Journal of Political Theory 14 no. 2 (2015): https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885114546; see also Reinhart Koselleck, “Crisis,” Journal of the History of Ideas 67 no. 2 (2006): https://doi.org/10.1353/jhi.2006.0013. To put it bluntly, Marx and Engels’ attempt to understand nineteenth century crises through the lens of the eighteenth century only led to disappointments. By the late 1850s, Marx revised his view and came to see crises as integral to the process of capital accumulation, and developments since the 1850s have only confirmed the accuracy of this approach. Economic crises under capitalism have not served as “opportunities” for revolution or progressive transformation. They have been pivotal moments through which the ruling class has reproduced its dominance over the world.

Marx is not the only one misled by history. Later, policymakers in Washington responded to the Great Depression of 1929 with passivity, having “learned” from the nineteenth century that economic crises tended to resolve themselves. In the 1970s, policymakers—particularly in Sweden—believed they knew their history when they confronted the crisis with active Keynesian countercyclical policies, which alleviated some immediate social problems but ultimately only postponed deeper structural issues.10In Legitimation Crisis from 1973, Jürgen Habermas discussed why the contradictions in capitalism do not cause economic crises, but only other types of crises, but this premise is difficult to sustain in light of what happened later that year, and beyond. Jürgen Habermas, Legitimation Crisis (London: Polity Press, 1976). Today, our understanding of economic crises and the policy tools used to address them are to a very large degree a product of the twentieth century. But are these insights still useful in understanding the 2020s? Or are we—like the young Marx—misled by the century just behind us?

Twenty-First Century Crisis – Twentieth Century Shadows

One significant feature of the twentieth century is that the Fordist-Keynesian era had relatively clear beginnings and ends.11My references to the twentieth and twenty-first century should not be understood as if there exist distinct epistemic regimes in different centuries that (should) change at the turn of every millennium. Further discussions on knowledge, history and crises will perhaps need more nuanced categorizations. A common reading of the century is to emphasize the transitions from some kind of liberal regime to Fordist-Keynesianism and to neoliberalism, and where the dramatic turning points—the 1930s and the 1970s/early ’80s—are often understood as periods of crises. This is the framework many of us—and indeed myself—were working in when we declared the end of neoliberalism in 2008. This periodization helped popularize the concept of interregnum: the time when “the old is dying and the new cannot be born.”12And as soon as something crazy happened, we referred to Gramsci and said that in this interregnum “a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1971), 276. Today, people born after we began waiting for the “new to be born” are old enough to drive. Are we still waiting for the birth of the new? Or is the twentieth century hanging like a nightmare over the brains of the living?

Rather than “thinking with” the twentieth century, what happens if we draw inspiration from the nineteenth century, when crises occurred roughly every nine to ten years? A brief look at the past fifty years reveals a similar temporality. Have we not seen economic crises in the capitalist core in 1973, 1982, 1991, 2000, 2008 and 2020?13This thought was already raised by David McNally in Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance (Oakland: PM Press, 2011), 38–40. As Michael Roberts might remind us, crises every decade can certainly coexist with hegemonic crises occurring every forty to sixty years.14Michael Roberts, The Great Recession: Profit Cycles, Economic Crisis. A Marxist View (London: Michael Roberts, 2009), 70. Even if periodizing according to “long waves” clarified the twentieth century—with turning points in 1873, 1929, and 1973— such a framework would not necessarily elucidate the crises of the twenty-first. However, the choice of temporality as a starting point for understanding current affairs carries significant theoretical and political implications. We must work from the hypothesis that the role, impact, and temporality of economic crises might differ from the ones we have seen over the last century. The next economic crisis might not come with as dramatic and abrupt changes in political economy as those of the twentieth century.15We might add here, in a parenthesis, that large parts of the ruling class are waiting for a technological revolution, to such a degree that their enormous investments in what they believe to be tomorrow’s breakthrough have themselves become a source of economic instability.

Perhaps the most important reason we remain intellectually anchored in the twentieth century is the place that neoliberalism has taken in left intellectual thinking. This concept’s advantage and weakness was its capacity to tie together related yet disparate phenomena. While politically helpful insofar as it allowed progressives to rally against something relatively concrete, the concept of neoliberalism was always a disaster for crisis theory. The vagueness and inconsistency with which the concept of neoliberalism was used blocked fruitful discussion. The mutual reinforcement between the spheres of politics, economy, and ideology during the period of neoliberal hegemony in the 1990s and 2000s alleviated these problems. However, in times of crisis, these problems caused by neoliberalism’s polysemy loom large.

The conceptual vagueness of neoliberalism becomes especially problematic when we try to understand the “end of neoliberalism”—that is, neoliberalism’s “terminal crisis.” While the 2020 crisis changed the political economy in different ways from the crises of 1992 or 2000 (for example)—changing the direction of capitalism, if you like—using neoliberalism does not clarify the matter. While much has changed dramatically (trade, ideology, politics, state management, and so on), other things have not—like the role of class. Despite turbulence since 2008, the balance of class forces has largely remained intact, in contrast to the rise and fall of Fordist-Keynesianism, which is often associated with relatively distinct changes in class power. If neoliberalism is primarily defined as a class project—a class revenge after decades of social democracy—it is tempting to argue that we still live under neoliberalism.16See for example David Harvey’s The New Imperialism. Many socialists have since the early 2000s been so engaged in discussions about neoliberalism that it has become hard to think beyond it. When Yanis Varoufakis suggests that we are experiencing the end of capitalism and are now in the onset of “technofeudalism,” I think this is the latest version of collapse theory: the crisis of neoliberalism misconceived as the final crisis of capitalism. To paraphrase Fredric Jameson, it seems easier to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of neoliberalism. David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199264315.001.0001; Yanis Varoufakis, Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2023). But keeping the same master framework used to describe the 1980s and 1990s not only obscures the dramatic political and economic changes that have transpired since then, but underestimates the capitalist class’s flexibility. Tech oligarchs Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, and Sundar Pichai easily turned from “neoliberals” to dutiful attendees of Trump’s second inauguration. Companies like Walt Disney and the Washington Post easily pulled back their focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The legacy of neoliberalism makes it harder to understand change in the 2020s.

Economic crises under capitalism have not served as “opportunities” for revolution or progressive transformation. They have been pivotal moments through which the ruling class has reproduced its dominance over the world.

Unlearning the Twentieth Century?

Like neoliberalism, the concept of fascism haunts crisis theory in the twenty-first century. These two concepts have been notoriously hard to define and the way they have been used to try to understand the 2020s have been very different. In contrast to the wide latitude scholars of neoliberalism have taken, scholars of fascism have often defined their object quite narrowly. Fascism is often described or defined by a list of components—often including interwar Germany and Italy, such as palingenetic ultranationalism, the crushing of all political opposition and Gleichschaltung (“bringing into line”), the cult of a leader, violent street gangs, and so on.17For recent discussions, see for example. Enzo Traverso, The New Faces of Fascism: Populism and the Far Right (London: Verso, 2019); Andreas Malm and the Zetkin Collective, White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism (London: Verso, 2021), chap. 7; Alberto Toscano, Late Fascism: Race, Capitalism and the Politics of Crisis (London: Verso, 2023). On fascism as an ideology, a movement, and a regime, see Ugo Palheta, “Fascism, Fascisation, Antifascism,” Historical Materialism (blog), 7 January 2021.

This makes conversations about what constitutes fascism both clearer and more delineated than the discussions about what constitutes neoliberalism.

These discussions become significantly more challenging when attempting to define contemporary persons, movements, or states as fascist. If one adds too many constitutive components of fascism, there will always be something in the current situation that does not fit. Alternatively, no one expects Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy to reoccur in its exact historical form.18That current discussions about the far right (and fascism) are filtered through the lens of the twentieth century also give them a certain form. Is it “really” fascism if it doesn’t necessarily involve abolishing elections, but only making them meaningless? Is it fascism if not all opposition media is banned, but the public sphere is flooded with so much garbage that news becomes irrelevant? Can it be fascism if courts are not abolished, but only filled with loyalists? And if there are fewer paramilitary street gangs, but more “warriors” found on social media? I will return to some political implications of this discussion in the second part of this essay.

One factor contributing to cognitive dissonance is that many contemporary phenomena are commonly associated with both neoliberalism and fascism. The new rightwing politics are as xenophobic, nationalistic, and authoritarian as historical fascism, but are also libertarian and extremely individualistic. The economic planning, welfare, or taming of market forces that are associated with twentieth century fascism (rhetorically or in fact), do not exist today. The political visions of Trump, Bolsonaro, Milei, Musk, and many more are “a much more liberal and libertarian project of asserting the primacy of property rights and engendering safety and security,” in the words of Peter Bratsis.19Peter Bratsis, “The Everyday Causes and Contradictions of Trumpism,” Historical Materialism (blog), April 2025. Gilbert Achcar’s short piece “The Age of Neofascism and Its Distinctive Features” identifies what is new about neofascism in a productive way—for example, neofascists never define themselves as “socialists”—and provides strong arguments for designating the contemporary far right as neofascist. Gilbert Achcar, “The Age of Neofascism and Its Distinctive Features,” Historical Materialism (blog), February 24 2025.

Given the challenge of defining these concepts, it should not surprise us that this, to some degree, was always the case: many “original” neoliberal thinkers were basically profascist. Augusto Pinochet was standing with one leg in each camp, Fortress Europa was always a core feature of neoliberal Europe, Democratic presidents deported millions of people from the United States, and Joe Biden was responsible for a genocide. The current oligarchic-fascist tendency originates from the neoliberal ideology of meritocratic individual genius. Today’s neofascism emerges as a result of, rather than despite, decades of neoliberalism. Today, Trump is attempting to finance kickbacks to the same class that benefitted immensely from the neoliberal decades, through both an assault on the public sector (that is, “neoliberal”) and tariffs (“nonneoliberal”).20For a good discussion, see also Richard Seymour, Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilization (London: Verso, 2024), 45-47.

There are two last lines of defense for people who insist on maintaining the twentieth century as the main point of reference for understanding the twenty-first. One is the concept neoliberal fascism.21See for example C.J. Polychroniou, “Neoliberal Fascism Is Now the Dominant Ideology in the United States of America,” Common Dreams, November 11 2024; Kerem Alkin, “The new Global Threat: Neoliberal fascism,” Daily Sabah, May 5 2023. Such conceptual amalgamation extends the already broad use of neoliberalism to describe its apparent authoritarian obverse: authoritarian neoliberalism, conservative neoliberalism, or reactionary neoliberalism, and so on. The concept of neoliberalism becomes useless if it can be used to describe any form of capitalism. The other line of defense is to insist that neoliberalism must be alive if we cannot define a coherent system replacing it. Working within this framework, if neoliberalism was a master signifier used to describe very different things, it must be replaced by something else more or less simultaneously in all spheres of life.

Much of the current debates on fascism must be read in this light. Is fascism the singular successor to neoliberalism? Just like neoliberal fascism, this way of framing the problem doubles down on the confusions caused by conceptualizing the 2020s through the terms of the twentieth century. The concept of neoliberalism was always problematic, and will become increasingly more so as with subsequent economic developments. It would be a major mistake to use neoliberalism as a lens, theory, or entry point to understand the 2020s. Whether neoliberalism is dead is the wrong question: it must be unlearned.

To understand the 2020s on their own terms is a major challenge. What does that really mean, both politically and epistemologically? Is it even possible to catch up with reality, when we are de facto children of the twentieth century? How can we discuss political change in the 2020s, and even the next crisis, without either overestimating or ignoring the twentieth century? How can we learn from history, while acknowledging that history does not repeat itself—hardly even as a farce; it is simply us, humans, trying desperately to make sense of the complex reality we inhabit.

One starting point in order to make sense of the 2020s beyond the twentieth century is to improve our work on making distinctions—or rather, to make better abstractions.22Don Mitchell, “There’s No Such Thing as Culture: Towards a Reconceptualization of the Idea of Culture in Geography,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20, no. 1 (1995): 102–16, https://doi.org/10.2307/622727. I mean this in three ways. The first is to use distinct concepts to analyze different aspects of society, in contrast to the blanket use of concepts like neoliberalism. Here, the postwar decades can be a source of inspiration. During the postwar decades Fordism described production, Keynesianism referred to fiscal and monetary policy, in many places social democracy referred to dominant political movements, colonialism described some international relations, modernism discussed art, and so on. Since the turn of the millennium, all these and so much more were reduced to a single concept.

A second starting proviso is to distinguish between levels of abstractions. Rather than having a single concept—like neoliberalism—to describe anything from individual feelings to world systems, phenomena should be conceptualized at a level of abstraction appropriate to them. Here it is worth mentioning the resurgent use of the concept of capitalism.23Just to mention some titles published between 2014 and 2018: David Harvey’s Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, Arundhati Roy’s Capitalism: A Ghost Story, Paul Mason’ Postcapitalism, Anwar Shaikh’s Capitalism, Jürgen Kocka’s Capitalism, Nancy Fraser and Rahel Jaeggi’s Capitalism and Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. I think it is fair to say this trend has since continued, or perhaps intensified. The naming of capitalism stands in sharp contrast to the 1980s and 1990s, when the concept largely disappeared from social sciences (see for example Bertell Ollman’s Dance of the Dialectic, and the third chapter of Andrew Sayer’s Realism and Social Science), with important exceptions like Peter A. Hal and David Soskice’s Varieties of Capitalism’, which tellingly emphasized capitalism’s spatial differentiation (which is true) at the expense of capitalism’s coherence and shared characteristics over time and space. David Harvey, Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014); Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything : Capitalism vs. the Climate (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014); Arundhati Roy, Capitalism: A Ghost Story (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014); Paul Mason, Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015); Anwar Shaikh, Capitalism : Competition, Conflict, Crises (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199390632.001.0001; Jürgen Kocka, Capitalism: A Short History, trans. by Jeremiah Riemer (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016); Nancy Fraser and Rahel Jaeggi, Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory, ed. by Brian Milstein (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2018); Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020); Bertell Ollman, Dance of the Dialectic: Steps in Marx’s Method (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 3; Andrew Sayer, Realism and Social Science (London: Sage, 2000); Peter A. Hal and David Soskice (eds.) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); Ian Bruff, “What about the elephant in the room? Varieties of capitalism, varieties in capitalism,” New Political Economy 16.4 (2011): 481–500, https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.519022. It is surely much better if the next generation of critical scholars become “experts on capitalism” rather than “experts on neoliberalism.”24The number of researchers who have neoliberalism as their “expertise,” “research interests,” or even “theory,” has indeed kept the concept alive longer than it should. That many scholars are still “experts” on the twentieth century—teaching and publishing on the subject—also explains some of what is discussed above. While capitalism refers to the overall social order in which we live, we must never underestimate that capitalism can take very different forms. We might also need concepts for what the regulation school has called the “regime of accumulation,” but then we must be careful that such concepts do not expand into territories where they confuse more than they clarify. These reflections underline a central point: rather than relying on a single concept to describe anything from individual feelings to a world system, we need politically useful concepts with a higher level of specificity.

The third form of distinction important to our understanding of the 2020s are those between different yet related crises, and between crisis and pseudocrisis.

The Shock Doctrine Coming Home

The 2020s marked a major shift in discussions of crisis amongst leading politicians, capitalists, and commentators. During the 2010s, their political project avoided any significant changes to the economy and existing class relations. This was crisis management at a superficial level, using lower interest rates, cheaper money, and increased debt to maintain the status quo. But as underlying problems remained unresolved, politicians tried desperately to keep a dying economic order alive. The 2010s provide an interesting example of capitalist rulers’s attempts to avoid change in a changing world. During this time, everything was done to suppress any sign of crisis.

In sharp contrast, during the 2020s, political and economic elites not only recognized but actively celebrated the ongoing turbulence. For example, in March 2025, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer said that this was an opportunity to reshape the economy: “The real world is moving quickly and people look to their government not to be buffeted about by that change—not even to merely respond to it—but to seize it and shape it for the benefit of the British people.”25Quoted in Jessica Elgot and Patrick Butler, “Starmer decries ‘worst of all worlds’ benefits system ahead of deep cuts,” Guardian, March 10 2025.

The concept of polycrisis is a telling example of how the ruling class came to embrace crisis. The term had previously been articulated by former president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker, and has now been celebrated by former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers. In 2022, polycrisis became a Financial Times word of the year, and was reportedly on everyone’s lips at the 2023 World Economic Forum.26See Jonathan Derbyshire, “Year in a Word: Polycrisis,” Financial Times, January 1 2023; Susan Geist, “What Is a Polycrisis, Why Is Everyone Talking about It and How Could It Affect Your Business?” mcgregor-boyall.com, March 22 2023; Adam Tooze, “Defining Polycrisis: From Crisis Pictures to the Crisis Matrix,” adamtooze.com, June 24 2022. For a critique, see Ville Lähde, “The Polycrisis,” Aeon, August 17 2023, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/15041.003.0005. The use of polycrisis signals the ruling class’s new message to the world: we know the situation is chaotic and we will solve it! The ruling class seems ready to exploit any opportunities arising from crises—real or fabricated.

This rhetorical shift had a material basis: the 2010s saw the weakest post-recession recovery since 1945, but also the first decade since 1945 without major downturns in the dominant economies.27Michael Roberts, “Forecast 2020,” The Next Recession (blog), December 30 2019. thenextrecession.wordpress.com

In contrast, the 2020s have been turbulent. They have thus far given us the COVID-19 pandemic, global supply chain problems, inflation, the so-called cost of living crisis, the “energy crisis,” severe stock exchange crashes, wars, a live-streamed genocide, geopolitical instability, and Donald Trump.

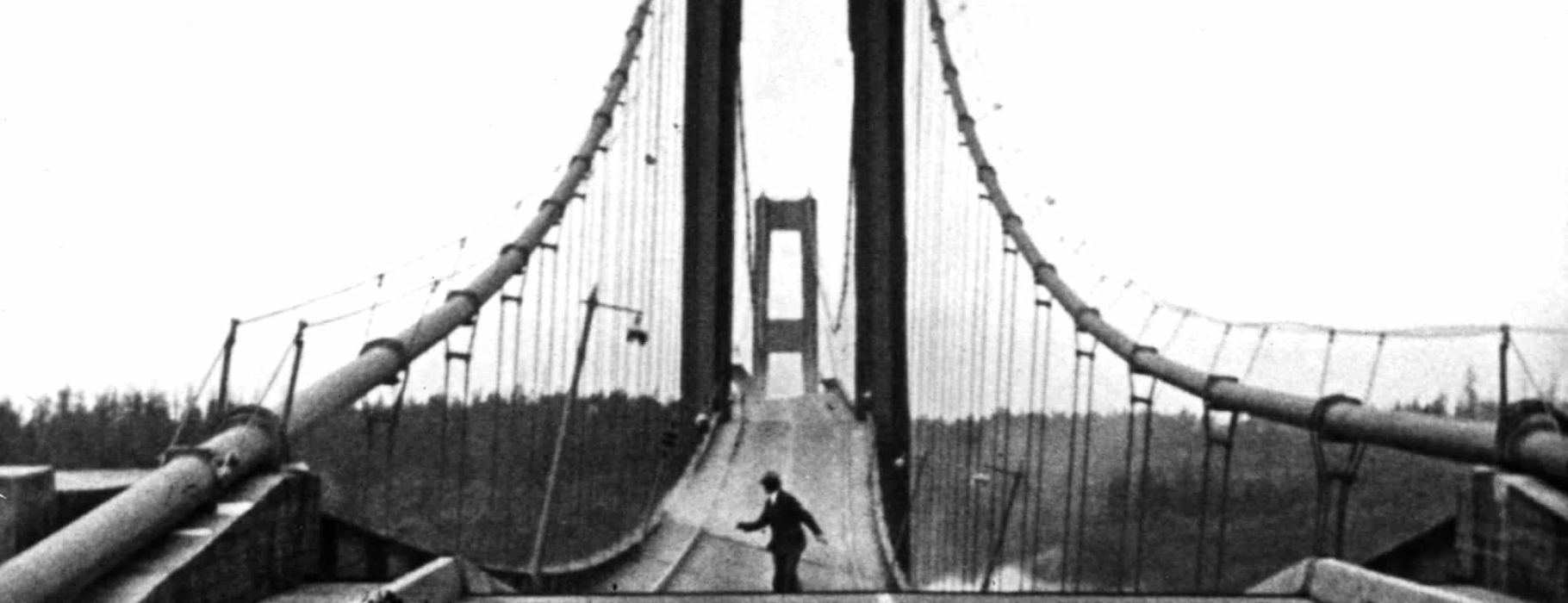

Trump intentionally introduced his April 2 “Liberation Day” tariffs as a spectacle. Rather than gradually impose tariffs so that businesses, politicians, and journalists could adapt to the new situation, Trump immediately placed tariffs ranging from 30 to 49 percent on numerous countries. His signal to the whole world was clear: this is the shock, chaos is coming!

Vice President J. D. Vance’s response to the tariff panic should not surprise us: “We’re feeling good. Look, I frankly thought in some ways it could be worse in the markets, because this is a big transition.”28Vance quoted in Gustaf Kilander, “‘We’re feeling good’: Vance insists market implosion could have been worse after shock Trump tariff announcement,” Independent (UK), April 4 2025. When Asia’s key indexes tumbled a few days later, Trump responded in kind: “I don’t want anything to go down. But sometimes you have to take medicine to fix something.”29Trump quoted in Helen Davidson and Phillip Inman, “European markets slump as Trump says ‘you have to take medicine,” Guardian, April 7 2025.

Introducing the tariffs as a shock could be seen as Trump’s “style,” or a strategy to force countries to negotiate “deals” with the United States, but it also reflects the zeitgeist of the 2020s. The decade has so far been characterized by both conspiracies and antiestablishment sentiments that accelerated during and after the pandemic, as well as seemingly everpresent crises and turbulence. In this situation, why not be the one who defines which crisis sets the agenda? If turmoil seems inevitable, why not be the one to initiate and steer it?

This is of course complicated territory. If the tariff shock actually had triggered a fullblown economic crisis, Trump could be blamed when millions of people started losing their jobs and homes. The days after “Liberation Day” displayed Trump’s method of navigating between political neofascism, economic nationalization, and a class policy that pleased his billionaire allies.30These kinds of power struggles are only possible because there is relative autonomy between the economic and political spheres. But central here is that Trump seeks to implement dramatic changes in the political economy through turbulence, which became even more evident when the National Guard were sent to cause chaos in Los Angeles in June 2025.

Trump’s tariff shock initially hit the stock markets hard and caused political turmoil, but it did not result in a general economic crisis. Today, there is so much talk about crisis that it is almost surprising to recognize that we are not currently living through an economic crisis.

These developments do not come out of nowhere, nor are they unprecedented novelties. Since the mid-2010s, leaders and liberal politicians have searched for new ways of organizing the political economy of Europe based on two premises.31This had different political expressions: grand coalitions between social democrats and conservatives (for example, Germany 2013–21), conservatives and liberals going into alliances with the far right (for example, Sweden 2022–), liberals converting into far-right populists themselves (for example, UK 2019–22), or “large scale” “green,” projects either through spending and subsidies (for example, the Biden administration) or in political ambitions (for example, the EU’s green deal). And then there was Liz Truss, the UK prime minister who in 2022 wanted to test one last time if neoliberalism really was dead. She suggested abolishing the income tax for the rich in an ongoing inflation, which roiled financial markets, sent the British pound into a tailspin, and UK pension funds came close to collapse. This search can continue today, because the working class and the political left are too weak to be any threat. The first is that class power would remain unchanged. This remains the case, and given the privileges the ruling class acquired between 1980 and 2010, this premise complicates such a reorganization. The second is that this transition would be civilized and moderate. This is hardly the case now.

Naomi Klein published The Shock Doctrine in 2007, describing how moments of disruption are exploited—and sometimes even created—by those in power. I assume that a vast majority among the ruling class and leading politicians have never read the book. Regardless, a large number of them have lived the books’ argument as reality. The Shock Doctrine examined how the United States created and used turmoil to discipline foreign governments. This time, the policy came with a different geography, since the sense of emergency was used to change social relations and political systems within the capitalist core. The chickens came home to roost.

Embracing the 2020s: Breaking It Down

The concept of polycrisis reproduces two core problems in crisis theory: it fails to define crisis and does not understand the interconnection between disparate crises beyond the surface level.32For a thorough discussion on the relationship between various crises of capitalism, see Holgersen, Against the Crisis, chap. 3. Rather than starting analytically from the notion that everything is in crisis—or that everything is one crisis—we must break down the components, connect the dots, and see how they constitute an organic crisis. Distinguishing between real and pseudocrises is equally important.

Let us begin with the most important crisis. So far in the 2020s, the world’s leaders and mainstream media have largely ignored global warming. While the scramble for critical minerals shows that no one can dismiss the fact that the fossil fuel era will end, global warming as an ecological crisis—one that actually kills poor people—can basically be overlooked. Whenever other crises or moments of turbulence emerge, the climate crisis is quickly pushed aside. It is always treated as the crisis that can wait. Even as global warming intensifies, the next economic crises will likely also squeeze the political space for climate movements. Even when other crises are not stealing attention, as in the years leading up to 2008 and 2020, the climate crisis remains unresolved, because the core of the problem is so deeply embedded within the structure of economic growth and the accumulation of (fossil) capital.33One key difference between economic and ecological crises is that economic crises must be resolved in order for the system to reproduce itself—ecological crises do not have to be.

As the Zetkin Collective argues, the climate crisis can be ignored, or inverted: “The crisis is not climate change, but what ‘they’ (the ‘globalist’ elite and ‘woke’ mobs) are going to do about it. In this way, solutions to the ecological crisis are framed as the crisis itself.”34Zetkin Collective, “The Great Driving Right Show,” Salvage, September 23 2024. The authors of this piece are William Callison, George Edwards, Jacob McLean, and Tatjana Söding. Rather than confronting the real dangers of global warming, political actors might use the crisis as an arena for political struggle and create pseudocrises around issues like “western freedom,” “masculinity,” “western values,” or “wokeness.” The inverted crisis of climate change is one form of pseudocrisis. The “immigration crisis” is another. It was created in the corridors of power to actively impose authoritarian solutions through racist policy. While racism certainly also comes from below, as a political phenomenon the “immigration crisis” comes from above.

Another current pseudocrisis is a political “legitimation crisis.”35On legitimation crisis and crisis of authority, see for example Elmar Altvater, The Future of the Market: An Essay on the Regulation of Money and Nature After the Collapse of “Actually Existing Socialism” (London: Verso, 1993); Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 206–76. There are good reasons why there should be a political crisis of legitimation across the capitalist core. Given that numerous leading politicians have recognized climate change as the most urgent issue of our time, why has the complete failure to resolve it not triggered a major legitimation crisis? The short answer is that crises are not “moments of truth,” as Jared Diamond argues.36Jared Diamond, Upheaval: How Nations Cope with Crisis and Change (London: Penguin, 2020), 7. See also the first chapter of Holgersen, Against the Crisis. They are political battlefields, where power is executed and (re)produced.37Whether a phenomenon counts as a crisis is a political question: Laura Pulido and her colleagues have shown how the spectacular displays of racism during Trump’s first presidency helped obscure sweeping ecological deregulations. Crises are also good opportunities to legitimize unpopular reforms. Laura Pulido, Tianna Bruno, Cristina Faiver-Serna, and Cassandra Galentine, “Environmental Deregulation, Spectacular Racism, and White Nationalism in the Trump Era,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 2 (2019): 520–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1549473.

The Next Economic Crisis

Trump’s tariff shock initially hit the stock markets hard and caused political turmoil, but it did not result in a general economic crisis. Today, there is so much talk about crisis that it is almost surprising to recognize that we are not currently living through an economic crisis. While there are certainly all sorts of problems and concerns with the economy, they do not amount to the acute phase of an economic crisis—when companies go bankrupt, millions of workers lose their jobs and homes within days or weeks, and large-scale, immediate crisis management is required.

“When the system is healthy,” according to Anwar Shaikh, “it rapidly revives from all sorts of setbacks; when it is unhealthy, practically anything can trigger its collapse.”38Anwar Shaikh, “An Introduction to the History of Crisis Theories,” 219. I suggest “collapse” should be replaced with “economic crisis.” To assess the current system’s “health,” one can look at underlying tendencies in profit rates, productivity, unemployment, investment, innovation, and technology alongside political instability, cracks in hegemonic orders, and geopolitical tensions. These are crucial issues, but are not the focus here. We can also retrospectively examine whether shocks actually lead to crises. Given the many shocks since 2020—such as the recent tariffs, the stock market crash of August 5, 2024, or the inflation surge 2021–23—it is notable that none of them have triggered a general economic crisis yet.

We cannot know exactly when the next economic crisis will occur. It might happen between the time I finish writing this and when it’s published, or five years from now, but what we know is that the next economic crisis will eventually come. This uncertainty is something with which we must learn to live.

Given the state of things in the 2020s that I discussed previously, I think it is fair to assume that the next economic crisis will come from a turbulent situation, in a tangle of real and fabricated crises, real and fake news, and both legitimate and horrendous critiques of the political system. The 2010s are over. The rulers of the 2020s look ahead, into a storm of crises—both pseudo and real. Neoliberalism is dead, turbulence is nothing to fear, and crises are something to be used. This is the turbulent water in which we swim, before the next tsunami comes. The ruling class will be ready to capitalize on the next crisis and to use it to their advantage.

Let us hope the next economic crisis comes later rather than sooner. Not only because history shows that such crises harm progressive movements and disproportionately impact the poor, who pay the highest price, but because given more time, we have the chance to prepare and resist this pattern. The articulation of socialist strategies and the building of movements to confront the next capitalist crises are urgent political tasks. This will be the focus of the second part of this essay.