What Are We Waiting For?

Part 2: Socialist Reflections on the Next Economic Crisis

August 8, 2025

This two-part essay draws upon crisis theory and the history of economic crises to reflect on the current turbulence and the next economic crisis. The first part can be found here.1Ståle Holgersen, “What Are We Waiting For? Part One: Socialist Reflections on the Next Economic Crisis,” Spectre, August 5, 2025, http://doi.org/10.63478/PAF8E50M.

Despite having theorized crises for some 150 years, Marxists have found it difficult to translate these insights into a coherent socialist crisis policy when real crises shake the world. When crises erupt, socialists tend to retreat into either revolutionary phraseology or Keynesianism. How can socialists chart a clear path forward in stormy weather?

This, the second part of the essay, focuses on how we can think about economic crises in the twenty-first century. The first part of the essay proposed a reconceptualization of crises as societal paroxysms and identified current challenges—both in terms of the use of history and conceptual chaos—when discussing tomorrow’s crisis. This second part discusses what we should do. How can we work towards a socialist approach to crisis?

In the first part of the essay, we saw that economic crises are complex phenomena, and there is always much we cannot know about the next crisis. Here, we focus on something we can know—namely that all economic crises under capitalism include and are formed by class struggle. So what could a working-class response to crisis entail? Since economic crises bring with them creative destruction, it is time to ask what a socialist version of that might look like.

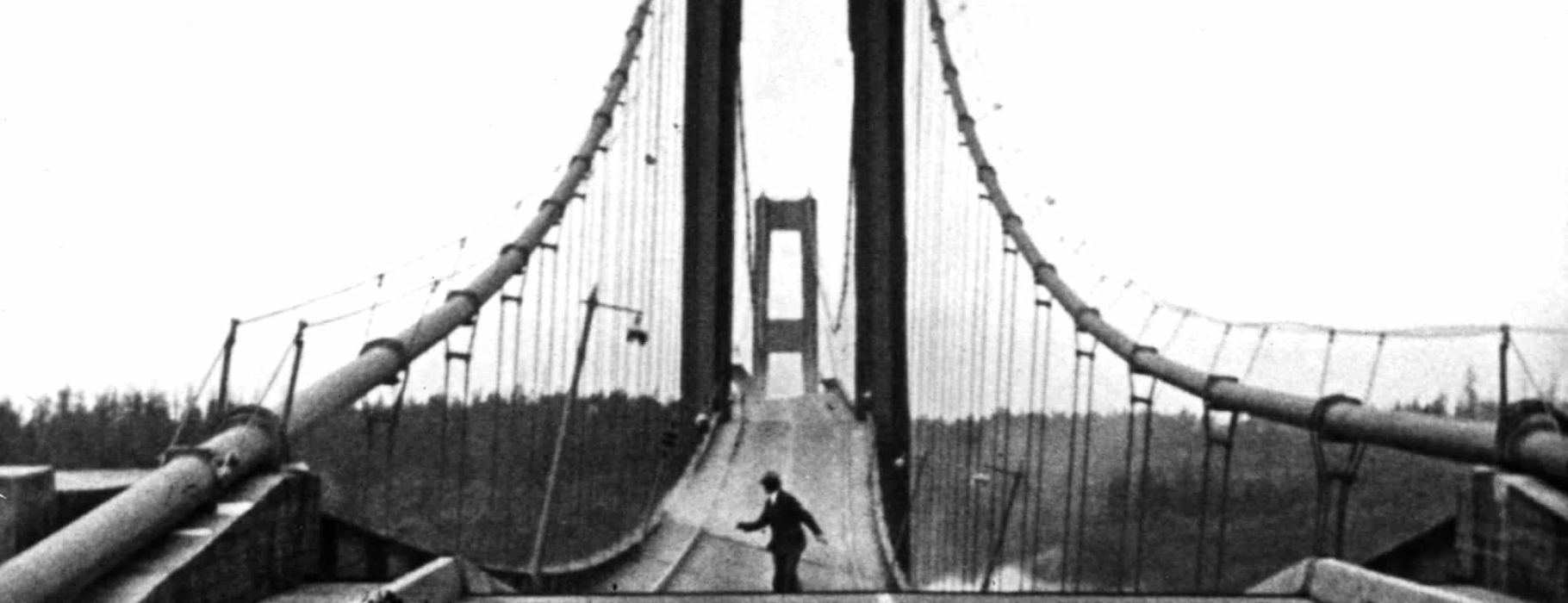

If socialists fail to discuss what to do before a crisis hits, it might already be too late. In moments of shock, we tend to act more on reflex, navigating between already established ideas. Such moments are rarely suited to deep intellectual or political reflection. When the world is on fire, it is difficult to seize control of the situation—unless one is ready.

I fully understand that many people may feel that there are issues that are more immediate and important than speculating about a future economic crisis. And indeed, there are also limits to how detailed plans for future crises can be. But I will stress that when the next crisis emerges, it is absolutely crucial to have already developed policies, slogans and plans—and ideally, a strong class consciousness—so that we know exactly which direction we are heading.

Point of departure: Beyond naïve optimism

Crises help us expose capitalism: suddenly we can see clearly the lies behind the theories of market freedom and self-regulating economies. While such insights are important, knowledge is not the main driver of historical development. Crises might help us expose capitalism theoretically, but they are, in actuality, central to the reproduction of capitalism.

Liberals often try to preserve the purported “sunny side” of capitalism (growth, progress, optimism) and mitigate (or eliminate) the persistent recurring disasters, either through active state policies and regulations (as with Keynesians and social democrats) or through privatization and deregulation (as with neoclassical and neoliberal thinkers). This liberal dream has been repeatedly shattered throughout history.

Marxists often succumb to an inverse image of this liberal dream. But the dream that the next crisis will lead to the collapse of capitalism and the age of socialism has been dashed just as many times as the liberal dream of a world without crises. While Marxist and socialist theories are useful tools for understanding crises, in actually existing capitalism the system is reproduced one crisis after another.

In 1959, John F. Kennedy noted that the Chinese word for crisis is composed of two characters: danger and opportunity. This “great wisdom” has since become commonplace in liberal and even some progressive circles. Commenting on the climate crisis in 2015, Al Gore notes that: “We all live on the same planet. We all face the same dangers and the same opportunities; we share the same responsibility for charting our course into the future.”2Cited in Robinson Meyer, “Al Gore Dreamed Up a Satellite – and It Just Took Its First Picture of Earth,” Atlantic, July 20, 2015. The idea that we all face roughly the same opportunities and dangers in economic crises is wrong, in the case of climate change, the statement is morbid.3According to Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature, Kennedy was wrong even linguistically, as the second character does not mean opportunity, but rather “incipient moment” or “decisive point.” Thus, not necessarily a time for optimism or a good chance of advancement, but certainly a period of change. See Victor H. Mair, “‘Crisis’ Does NOT Equal ‘Danger’ Plus ‘Opportunity’: How a Misunderstanding about Chinese Characters Has Led Many Astray,” pinyin.info, September 2009.

Framing crisis as “danger and opportunity” hides its class character: the opportunities accrue to those with economic, political, and ideological power, while the dangers fall on the rest of us. In crisis, the poor suffer, or die, first.4Ernest Mandel formulated this well in 1978: “[Any crisis] strikes the weak more harshly than the strong, the poor more harshly than the rich. This is true within the imperialist countries themselves, as the crisis affects the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. It is true within the employer class vis-à-vis the small and middlesized companies on the one hand and the great monopolies on the other. And it is true on a world scale, vis-à-vis the semi-colonial and dependent countries on the one hand and the imperialist countries on the other” Ernest Mandel, The Second Slump: A Marxist Analysis of Recession in the Seventies (London: NLB, 1978), 46). As a general rule, economic crises under capitalism have not been opportunities for working class and progressive movements. People might become angrier, but that anger can be mobilized in different directions. Without food on the table, it is difficult to dream of a better world and it is far easier to dream of food on the table. People desperate to find or keep their jobs will have more immediate problems than making revolution. Building on Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, we can argue that those with political, economic, ideological, and military power are most likely to be able to use the crisis to their advantage.5Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (London: Penguin, 2007). If opportunities are occasions that make it possible to do something, we must acknowledge that the crises of capitalism are not mainly opportunities for the working class, the environmental movement, or the political left.

Still, the left seems to have a hard time letting go of the idea that crises are opportunities. In a recent Jacobin paper “Don’t Cheer a Recession,” Meagan Day rightly points to the social problems that a coming recession will bring to the working class. She then presents “two theories of how crises affect social change,” one optimistic and one pessimistic, and concludes that “history offers no clear verdict on which is correct,” and gives “mixed signals about whether downturns help or hurt our cause.”6Meagan Day, “Don’t Cheer a Recession,” Jacobin.com, April 4, 2025. This is not true. History provides a clear verdict. To exemplify the “optimistic theory,” Day mentions the Russian Revolution and Sweden’s response to the Great Depression. But the Russian Revolution was not primarily a consequence of an economic crisis and certainly not a modern capitalist economic crisis as we know them today. The main factor was Russia losing a war, not an economic crisis. Additionally, as Clara E. Mattei shows in The Capital Order, the economic recession of 1920 was a crucial event that stopped the revolutionary wave in Europe in 1918 and 1919.7Clara E. Mattei, The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism (University of Chicago Press, 2022), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226818405.001.0001. As for Sweden, Kjell Östberg shows in The Rise and Fall of Swedish Social Democracy that the economic recovery in the 1930s was due mainly to trade with Nazi-Germany, and social investments, or reforms.8Kjell Östberg, The Rise and Fall of Swedish Social Democracy (London: Verso, 2024). The big welfare programs we normally associate with the Swedish model were mainly rolled out after the war.

The arguments that the crises in the 1970s and 2000s can be read through the “optimistic theory” because they contributed to resistance and demonstrations miss the massive difference between demonstrating and actually winning politically. The main conclusion from the economists Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick and Christoph Trebesch, for example—who studied economic crises in relation to over eight hundred elections—is that people demonstrate more after financial crises, but voters are attracted to parties that blame the problems on immigrants or minorities.9Parties on the far-right increased voter support by 30 percent on average after what the authors defined as financial crises. Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick and Christoph Trebesch, “Going to Extremes: Politics after Financial Crisis, 1870–2014,” CESifo Working Paper, No. 5553, (2015): 8–9, 33–4, and Appendix D, 53–5, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2688897.

Historically, crises have tended to be opportunities for the ruling class, and problems for the working class and progressive social movements.10This is further developed in Ståle Holgersen, Against the Crisis: Economy and Ecology in a Burning World (London: Verso, 2024). Note that this is a tendency, not an iron law. Exceptions exist, and the New Deal in the United States is perhaps the better one (even though this is a highly complicated matter).11Also developed in Holgersen, Against the Crisis. Our aim is to make more exceptions, with the final aim of mobilizing a socialist movement against the crisis.12For an interesting discussion, see also James Cairns, “The Worse, The Better: A Critical Commentary,” Socialist Studies/Études Socialistes, April 2025, 19(1), https://doi.org/10.18740/ss27366. But in order to do so, we must have a map that fits the terrain.

Solidarity in Headwinds

Crises are times when we need solidarity, but historically actual and active camaraderie within the working class, especially internationally, seems to become harder during crises. Notably, the class character of crises is frequently obscured by nationalism, national chauvinism, and racism. Nation-states always play central roles in crises for both institutional and ideological reasons. Institutionally, as crises come with demands for immediate crisis policies, nations and nation-states hold the power needed to immediately and effectively intervene into the economy. Ideologically, nationalism becomes a reflex among powerholders (as well as the far right) in turbulent times. The next economic crisis will likely unfold during a period of escalating militarization, geopolitical tensions, and warfare—as in the midst of the horrific livestreamed Zionist genocide in Palestine.

As a general rule, economic crises under capitalism have not been opportunities for working class and progressive movements. People might become angrier, but that anger can be mobilized in different directions.

Liberals, who must obscure capitalism’s role in producing crises, might blame the next economic crisis on any ongoing war.13For example, on August 5, 2024, with one of the major stock market crashes in the history of capitalism, it came directly: strong claims about wars contributing to economic turbulence without concrete explanations. On war and crisis, see also Rikard Štajner, Crisis: Anatomy of Contemporary Crises and (a) Theory of Crises in the Neo-imperialist Stage of Capitalism (Belgrade: KOMUNIST, 1976), pp. 66–7. By contrast, socialists have long argued that causality should be reversed: economic crises and economic problems can heighten the risks of new wars or escalate existing ones. Crises might increase geopolitical tensions, while wars might be the “creative destruction” needed to resolve the next economic crisis.

Crises divide the working class, as crises are racialized from all sides: the official “explanation,” allocation of suffering, and patterns of resolution of crises all tend to disadvantage racialized groups. Racism is permanent enough to be part of every capitalist crisis, flexible enough to adapt to new crises, distinct enough to reproduce (old) power relations, and toxic enough to kill. When the next economic crisis hits our societies, it will be experienced and lived by many through racism: this is “where the crisis bites.”14Stuart Hall, “Racism and Reaction,” in Commission for Racial Equality, Five Views of Multi-racial Britain (London: Commission for Racial Equality, 1978), 31. Stuart Hall and colleagues have shown how immigrants (alongside communist activists and “foreign agitators”) have historically been scapegoated for economic and social turmoil and crises. Today we may also add feminist activists, queer, and trans people.15Stuart Hall et al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (London: Macmillan, 1978), 50. The far right’s targeting of, for example, immigrants and Muslims will continue with the advent of the next crisis. All current antiracist organizing—and really, all antifascist solidarity work—is extremely important preparation for the next economic crisis that awaits us.

Beyond saving the system and burning down the house

In the absence of a proper strategic socialist approach to crisis, two other approaches are often taken. The first is to meet the crisis with a cry for revolution. This position manifests in revolutionary groups calling for a completely new system and academics urging us to “think beyond the system.” While these calls are valid in principle, they remain politically irrelevant. Shouting for revolution at people struggling with immediate concerns does not help mobilize them. And “daring to think” beyond the system is hardly the problem—getting there is what matters.

The other approach is to succumb to Keynesianism (by which I here basically mean countercyclical policies that boost consumption and increase state investments during crises, directed in more or less progressive ways). This is by definition a strategy for reproducing capitalism. Indeed, reproducing capitalism is a precondition for a Keynesian crisis policy to make sense in the first place.

Keynesianism is not a magical solution to all economic crises, since these crises also demand moments of reorientation and destruction. But even if it was, or if we accept it is the least bad crisis management that exists, could we first solve the crisis with Keynesian policies and return to conventional socialist class struggle once the turbulence is over? The problem here is that crises are so frequent in modern capitalism that such an approach would leave socialists perpetually occupied with propping up the system crisis after crisis.

Costas Lapavitsas has argued that while the Marxist tradition is good at understanding the medium- and long-term problems, it cannot be compared to Keynesianism when it comes to short-term crisis management.16Costas Lapavitsas, “Greece: Phase Two. An Interview with Costas Lapavitsas,” Jacobin, December 3, 2015. This is a fair argument, but more than anything, Lapavitsas has identified a problem that we must confront. This problem is especially important in the face of the climate crisis, as we simply cannot continue another century with compound economic growth if we are going to avoid devastating ecological catastrophes.17For a (friendly) critique of Green New Deals, see the sixth chapter of Holgersen, Against the Crisis. On eco-socialist strategy, for a critique of both left-productivism and degrowth, see Ståle Holgersen, “Neither Productivism nor Degrowth. Thoughts on Ecosocialism,” Spectre, September 4, 2023. https://doi.org/10.63478/1ZI9XRMU. So how can we think about a proper socialist approach to crises?

Levels of Resistance

One major challenge in developing a socialist crisis policy is the recognition that crises are, in fact, crises. As crises are social paroxysms—that is, events embedded in underlying structures and processes—they always exist on several levels of abstraction.18This is discussed in the first part of this essay. They are simultaneously shocking events, transformations in how we organize the political economy, and expressions of underlying tendencies at the core of capitalism. Just as the crisis exists on different levels, so too must a socialist approach.

We can distinguish between three levels. At the most general level, we need a socialist crisis critique—one that helps us understand the nature and history of capitalist crises, grasp the terrain we must navigate, and show how capitalism both produces crises and reproduces itself through them. Without engaging with theoretical discussions, we can never understand crises as they unfold. However, a movement that exists only, or mainly, on this abstract level will remain politically irrelevant. This is why we need concrete socialist crisis policies. This intermediate level is crucial to guide our actions when crises hit. These must be prepared in advance, to avoid falling into the Keynesian fishing net. As we cannot fully predict what the next crisis will look like, we also need—on a third and most concrete level—socialist crisis management. This involves short-term, hands-on responses to handle shocks and alleviate suffering from day one.

A socialist approach to crisis must develop all three levels—critique, policy, management—and, crucially, tie the levels together. This is no easy task. Yet, both Keynesians and neoliberals have been effective in this regard. When the crisis hit, Keynesians had an almost instinctive reaction: increase state spending and investments! This can take different forms, but the reflex is there, and it is rooted in an overarching understanding of political economy. For neoliberals, at least until recently, the reflex has been to privatize, deregulate, cut taxes, and bail out banks. Again, these responses vary in form, but are also connected to a broader theoretical framework. Socialists, by contrast, lack a reflexive response that ties coherent socialist analysis to the immediate demands of a crisis.19A key difference is that Keynesianism and neoliberalism are top-down projects aimed at reorganizing capitalism, while socialism is a movement from below, seeking to break beyond the existing system.

While crises exist on several levels, their shocks on the surface invariably absorb us, capture our attention, and steer political discussions. Many commentators correctly observed that the economy was heading into a crisis in the fall of 2019. This was soon forgotten when the extraordinary shock of Covid-19 shifted all the focus to the virus, obscuring underlying problems.20Speculations about what the next crisis would look like ranged widely in the late 2010s: a dramatic fall in oil prices, a possible US-Iran war, trade conflicts between the US and China, Brexit, a breakdown of the Italian economy, or unsustainable levels of private and public debt. Hardly anyone could have foreseen what actually unfolded just weeks later. Most likely, there would have been an economic crisis around 2020 even without Covid-19, and then we would now remember it as the “new oil crisis,” the “trade crisis,” the “Brexit crisis,” the “Italian crisis,” or the “debt crisis,” depending on what triggered it. Political discussions during the next economic crisis will likewise be absorbed by that crisis’s triggers. If Trump’s 2025 tariff shock had sparked an economic crisis, self-satisfied liberals would likely have declared that Trump alone was to blame, ignoring the political and economic minefield of the 2020s, suggesting myriad causes external to capital’s political economy. The fact that crises systematically reappeared for two hundred years would likely be largely forgotten.21For examples of schadenfreude among Democrats and liberal commentators when it looked like Trump was sending the economy into recession, see Day, “Don’t Cheer a Recession.” While the political focus on the surface may be frustrating for many Marxists (who are experts on the underlying structural tendencies), it is absolutely crucial for socialist movements to also intervene forcefully in discussions at the surface level.

Combining crisis critique, policy, and management necessarily involves different forms of knowledge, which entails a collective effort involving socialist activists, cadres, organizers, politicians, intellectuals, and others. Consequently, socialists must build on general insights while standing firmly within the communities affected by crises.

Socialist plans for the next crisis can take various forms. Some of us have a weak spot for writing programs, but socialist preparations do not have to take the form of a formal, printed plan. We need to collectively build a political culture and consciousness, focusing on key issues over time, strengthening our antiracist muscles, and fostering class hatred. But at a minimum, there must be some shared understanding of who our main antagonists are and the kinds of demands that will be immediately raised when the crisis erupts.

A socialist approach to crisis must develop all three levels—critique, policy, management—and, crucially, tie the levels together. This is no easy task.

We must mobilize the masses and prepare for the coming economic crisis. But there is no “first,” and “then” here. We cannot first make a program and then build a movement, or first gather a movement, and then create a plan. This must develop organically and simultaneously. A socialist crisis program without a movement holds little value. But huge rebellions or mutual aid in communities are helpless without any political direction.

For an Ecosocialist Creative Destruction

Crises are serious situations that unfold rapidly: they create a sense of urgency where people demand immediate political action. The urgent nature of crises is one reason why socialists so often end up in the “Keynesian fishing net”—voting for Keynesian investments programs that seek to save capitalism because not doing anything is no alternative. When we are told “we only have a decade,” even much of the climateconscious left bends its neck and accepts the Clintons and Bidens, because the alternative is Donald Trump.

The sense of emergency matters. Naomi Klein highlights in Doppelganger the importance of remaining calm in the face of shocks.22Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World (London: Allen Lane, 2023), chap. 11. It is hard to argue against the virtue of staying calm. And indeed, with some pseudocrises (like the “immigration crisis”), it is certainly smart not to get carried away by the agenda set by our political enemies and let them define what counts as a crisis. But real crises are more than discourses; sometimes the world is literally on fire. When people see their jobs, houses, and welfare disappear and demand immediate action, a political strategy of staying calm is insufficient. As a political project we should rather “panic together,” albeit in an organized manner.

Economic crises come with creative destruction. This is a process constituted by three interlinked moments: first, devaluation and destruction; second, the implementation of new ways of organizing the economy, new class relations, new technologies, and new regulations to replace the old ones; and third, new investments. Socialists have previously been theoretically most concerned with the first, and politically most interested in the third. But all three components are crucial: the disruptive, the transformative, and the constructive.

Socialist preparations for the next crisis should work within this framework: what could a socialist creative destruction look like? What sectors do we want to see destroyed (for example, cryptocurrencies, the fossil sector, and so on)? What kind of crisis management alleviates the suffering of the working class, while also pointing toward socialism? What services could be deprivatized immediately, and which sectors should be nationalized (instead of bailed out)? How can we (re)regulate the housing system? Which struggling companies should be placed under state control and which could work under workers’ control? How much should we tax the rich and luxury consumption? And, yes, massive state investments are indeed needed in most regions and countries. In times of economic crisis, they must, for example, directly alleviate suffering, quickly create the right jobs, and ensure a steady supply of food for the poorest. Adding global warming to the equation, we need huge investments in infrastructure, housing, and energy. But this must be embedded in a broader socialist framework guided by the needs of people and the planet, and not based on a Keynesian logic on simply boosting consumption to restore private profits.

Class Struggle Against the Crisis

Writing on the 1857 economic crisis in Hamburg, Karl Marx noted that the city tried to stem the crisis by socializing the capitalists’ losses: “this sort of communism, where the mutuality is all on one side, seems rather attractive to the European capitalists.”23Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme, in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Selected Works, vol. 3 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970 [1875]), 13–30. This is the crisis management we have grown used to, where risks are socialized, rewards are privatized, and workers pick up the bill when a crisis hits.24Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (London: Anthem Press, 2013), chap. 9; Yanis Varoufakis, “Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World: Review,” Guardian, August 12, 2018.

The class character of crisis policies should not surprise us. They emerge from, play out in, and are resolved within a class society. The millions living paycheck to paycheck will pay the hardest price for an economic contraction. The degree to which the upper layers of the working class are affected will of course differ between crises. But given the current situation, not least in the United States, we can easily imagine that even these sections will be seriously affected by, for example, massive crackdowns on the public sector, universities, civil rights, labor unions, and more. Economic crises are not “resolved” when people can work, pay rent, or afford food but only when profits rates have recovered. The class distribution of those saved during an economic crisis reveals the class nature of every crisis. To save the system, capital must be saved.

A socialist approach, in short, should rest on four interwoven principles: alleviating the burdens on the working class, uniting the broad working class, steering crisis policies toward socialism, and clearly identifying the capitalist class as the enemy.

As the crisis hits, we need to immediately launch concrete programs for jobs, food, and housing, as also discussed above. The second principle is to unite various social movements and help them find a common direction—toward socialism. This is not easy, and it never was. The working class has always been heterogeneous. While uniting the labor movement and environmental movements with antiracist movements, feminist movements, and the Palestinian solidarity movement (and more) is difficult, it nevertheless remains crucial. If you are a socialist activist that has tried and failed in uniting various social movements for decades: try again. Thirdly, all crisis management must be steered in a socialist direction, and here we must be pragmatic, and include both state ownerships and workers’ coops, for example. But fourth, a left response to crisis cannot be limited to alleviating suffering among the poor: to challenge power relations in society, we must also confront the rich.

Reducing the personal wealth of the most affluent should be a central demand as soon as the crisis hits. This will be articulated differently in various places. Analytically I prefer the concept capitalist class, but when translated into a political language to mobilize the whole class it might work better with the “rich,” the “1 percent,” the “oligarchs,” or even the “economic elites.” The actual arguments for taking their wealth might also differ: they don’t deserve the money in the first place; the working class have paid for the last X crisis, now the billionaires must pay; or that extreme concentration of wealth is being converted into political power; tax the rich—save democracy!

A socialist crisis policy might be directed toward the ruling class as owners with arguments that the crisis shows we need other forms of ownership, but also toward them as extremely rich. Their conspicuous consumption might provide opportunities for class hatred, as their extreme luxury will be even more grotesque when more people face increased poverty in the next crisis. Given the escalating climate crisis, ban private jets. Not primarily because this would lower global emission dramatically, but because it produces the enemy lines we want and points in the direction we want to see the crisis policy move. And—of course—no one should fly private jets in a burning world.

Antifascism as Crisis Management?

In 1921, Antonio Gramsci characterized fascism as “the attempt to resolve the problems of production and exchange with machine-guns and pistol-shots.”25Antonio Gramsci, “On Fascism, 1921,” in David Beetham (ed.), Marxists in the Face of Fascism (Chicago: Haymarket, 2019 [1921]), 82–3. The petty bourgeoisie, Gramsci continued, believes that gigantic crises can be solved with machine guns and military force. If the petty bourgeoisie really believes this, then we must agree with them. Economic crises can be solved with machine guns and war.

When the next crisis erupts, we will bring fighting spirit and knowledge about the nature of crisis into the ring. Then we will be ready, and then we will win.

As discussed in the first part of this essay, the increased strength of the far right is an important political issue with huge consequences for the way we think about and respond to crises in the 2020s. In more and more places, the struggle against the far right will be a substantial part of a socialist crisis policy. One important historical lesson is that fascism tends to radicalize as it wins. When suppression and violence are the means, they escalate their methods in response to new challenges. Fascism does not stop until it is stopped. Another lesson is that fascism is an answer to crises.26Nicos Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship: The Third International and the Problem of Fascism (London: Verso, 2018). It is a way of reproducing capitalist social relations though crisis by the means of authoritarian, antidemocratic, antifeminist, racist, and, indeed, antisocialist policies. If real crises are lacking, they must be created. The next economic crisis might be used exactly to push society towards fascism, a push that may be accelerated by a fusion with various pseudocrises.27On the role of pseudocrisis, and especially in the 2020s, see the first part of this essay.Ståle Holgersen, “What Are We Waiting For? Part One: Socialist Reflections on the Next Economic Crisis,” Spectre, August 5, 2025, http://doi.org/10.63478/PAF8E50M.

In the interwar period, fascism became a solution when even the ruling class feared that capitalism itself could go under.28For example on March 5 1934, the New York Times ran the headline: “Capitalism Is Doomed, Dying or Dead.” See Matt Huber, Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 33, https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816677849.001.0001. On 1918–20, see Mattei, The Capital Order. This is different now. We are again living with turbulence, crises, and pseudocrises—not least the climate crisis, which should prompt reflection on capitalism’s future—but hardly any members of today’s ruling class can imagine a world without capitalism.

The current ruling class does not have to legitimize their power to anyone. Whereas the ruling class after World War II remembered how the working class had gained ground during the first half of the decade, and the ruling class under the 1980s and 1990s could still remember that the working class had exercised power (not to mention the existence of the Soviet Union), the current rulers have only seen turbulence and crises work in their favor. This provides a different—almost opposite—explanation for the current willingness within the ruling class to align with fascists as compared to “historical fascism.” The world is turbulent, yet they cannot even imagine losing. If securing greater profits, and for some global dominance, requires alliances with hate speech and the dismantling of democratic institutions, they will take that path. This should remind us, among other things, to distinguish between the flexibility of the ruling class’s strategy and the inexorable pull of their profit motive.

Current debates on fascism often boil down to say, whetherTrump is or is not a fascist. I find this question less important. What matters is that Trump’s policies—and those of many similar yet distinct far right parties across the globe—are moving in such a direction. And they will only stop when they are stopped. This is often conventional wisdom for many ordinary people. This is knowledge production from below—from the depth of the working class—by those who have experienced this evil face of capitalism. These everyday experiences of ordinary people are not only important in its own respect; this is also crucial knowledge for socialist crisis policies and management.

More important than what we call a certain politician or party—fascist, or neoliberal fascists, or dark conservative, or rightwing authoritarian—is what we call ourselves: the resistance. Given the current situation it will make sense in many places to face the crisis under the banner of antifascism. This is certainly something we can learn from history: embracing the proud tradition of antifascism.

The main aim for any socialist movement is always to unite as large parts of the working class as possible, and wed social and progressive movements more tightly to a socialist direction. This is, and has always been, a difficult task. Doing so in the midst of a crisis and the emergence of the far right might seem impossible. But it is not. And in some places, antifascism might be the antidote. Defensive struggles must protect what is worth defending, but both antifascism and socialist crisis policies are most effective when we take the offensive.

Sometimes, uniting the broad working class or social movements becomes easier when external forces push us together. The far right will continue to attack progressive institutions, labor unions, feminist movements, antiracist movements, and of course the environmental movement. We should have no naïve optimism about this, nor should we romanticize it. The aim of any far right movement is to divide the class along the lines of race, culture, religion, sexuality, and so on. But if we are prepared, such attacks can make it easier to see what unites the broad working class. If so, this is surely an opportunity we must seize—antifascism as the force that brings us together.

The far right hates class struggle and must crush the organized working class to win. In the next crisis, we should insist that billionaires and oligarchs must pay while facilitating worker-led cooperatives and strengthening unions. Fascists always defend the capitalist system even as they pretend to rebel against it. In the next crisis, we should demand the nationalization of banks and let the fascists sit with the “respectable” bourgeois parties to defend the moribund financial system. The far right prefers not to be reminded of global warming. In the next crisis, we should launch massive investment plans in publicly owned renewable energy. Fascists are often antisemites but must support Israel for imperial and colonial reasons—which we will never forgive or forget. As soon as an economic recession emerges in Israel, we should intensify the BDS movement. Fascism depends on racism. When the next crisis hits, we must keep our communities together, defend one another, and push forward with antiracism. In the current mix of real and pseudocrises, the reactionary forces are coming for trans people first. We will not be fooled by their pseudocrisis. We must protect our communities, then we attack.

We can win

Never let anyone tell you otherwise: we are strong, we are many, and we are already doing so much right. A lack of confidence in ourselves can be as limiting as actual weakness. There is a danger in thinking that because we have lost so many battles over the last decades, we need to abandon our strategies entirely and invent brand new ways of organizing. There is no reason to be naïve. Historically, crises have not worked in our favor. But after all, there are also reasons for optimism. Not because of the crisis, but because we are humans. The potential power of the broad working class and the broad left is always massive.

Writing from 2025, we must recognize that we actually have some experiences in fighting. Since the turn of millennium, we have seen many examples of resistance. These have often failed, but they gave us experiences: from the antiglobalization and antiwar movements to the Arab Spring; from the movements of the Squares to environmental struggles in various forms; from BLM and Palestine solidarity to countless antifascist mobilizations; from LGBTQ+ and pensioners’ rights struggles in Latin America to housing movements that often go under the radar but are organizing in communities across the world. We know that crises are not “moments of truth”: they are battlefields. We are the generation that read Klein’s Shock Doctrine. Perhaps this makes us better prepared to confront the next crisis than the generations before us. We know that the ruling class today is extremely self-confident, but this is pride coming before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall. When the next crisis erupts, we will bring fighting spirit and knowledge about the nature of crisis into the ring. Then we will be ready, and then we will win.

My contribution here has been too broad and general to be directly applied in a future crisis. But hopefully, it has provided food for thought and helped steer the discussion in a fruitful direction. From here, we must develop socialist movements, demands, slogans, and programs to prepare for the next economic crisis. And in order to win the crisis, as much as possible must be done before the next crisis hits. What are we waiting for?