Knowledge Without Fear

Building Solidarity with Chinese Academics Against Great Power Conflict

February 3, 2026

Introduction

In August 2025, President Trump announced that he would allow six hundred thousand Chinese international students to study in the United States, which nearly doubles the number of Chinese students currently enrolled in US universities. This announcement sharply contradicted his administration’s stance just three months after Secretary of State Marco Rubio vowed to “aggressively” revoke visas from Chinese students.1Anemona Hartocollis, “Trump says he welcomes Chinese students, as his administration blocks them,” New York Times, August 26, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/26/us/politics/trump-chinese-students.html. Trump’s reversal drew immediate backlash from prominent MAGA figures, yet again in November, he doubled down, insisting that admitting Chinese students was good business and that banning them would be “insulting.”2Laura Zhou, “Donald Trump defends policies amid pushback over Chinese students, H-1B visas,” South China Morning Post, November 12, 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3332522/donald-trump-defends-policies-amid-pushback-over-chinese-students-h-1b-visas.

While many observers were right to note that Trump uses Chinese student enrollment as leverage in ongoing trade negotiations with Beijing, both his decision to single out the issue and the broader MAGA movement’s fixation on Chinese students are not incidental. For decades, the growing presence of Chinese international students and the expansion of scholarly exchange between the United States and China were critical to the symbiotic relationship that sustained neoliberal globalization. These exchanges embodied neoliberalism’s core promises: the free movement of capital, knowledge, and people; economic and scientific collaboration unfettered by geopolitics; and the belief that deeper integration would make other countries—chiefly China—become “more like us.” US higher education was fully woven into the neoliberal global project—commercialized, globally integrated, and structurally dependent on flows of talent, knowledge, and tuition revenue across borders.

But the promises of neoliberal globalization proved illusory. Its deepening inequalities and dislocations fueled a violent popular backlash against the very institutions that had championed global integration, especially universities which became bastions of elite privilege, cosmopolitan values, and globalist power. At the same time, in the United States, China came to embody neoliberalism’s failures: China was blamed for the worst effects of deindustrialization and feared for its growing economic clout, state-led industrial successes, persistent authoritarianism, and territorial assertiveness. These issues have been subsumed into a broader narrative of great power competition, one that panders to nationalist impulses at home, and seeks to fortify a declining US hegemony in the global economy. As Washington elites soured on China, commercial, scientific, and educational exchanges long encouraged were reclassified as national security vulnerabilities.

The targeting of students and scholars of Chinese descent beginning in the first Trump administration simultaneously undermined the material foundations of neoliberal institutions and structures of growth, while isolating a convenient “alien” population onto which popular discontent can be displaced. Trump 2.0 has only intensified this dynamic through widening the assault on universities. What began with Chinese students and scholars has since expanded into a sweeping campaign against all immigrant academics and racialized “others.” Accusations that legitimate US-China scientific and scholarly exchanges were acts of “disloyalty” have now metastasized into attacks on campus free speech, DEI programs, gender and ethnic studies, and a growing list of purportedly “un-American” activities.3“Against the New McCarthyism: Organizing Resistance in Higher Education,” YouTube video, 1:26:50, posted by “Haymarket Books,” September 15, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/live/AokV9UO14ek; Ashley Smith, “Against the New McCarthyism Building the resistance after the Kirk assassination,” Tempest Magazine, https://tempestmag.org/2025/09/against-the-new-mccarthyism/.

Seen in this light, the targeting of Chinese students and scholars was never an isolated episode, but a precursor to the broader reactionary movement against higher education unleashed by a collapsing neoliberal order—one that can only be confronted through building collective power.

The Rise of the US-China Great Power Conflict

Great power competition with China has come to define US foreign policy and shape many domestic priorities. The rare bipartisan consensus and near obsession among US politicians with bringing China to its knees has rapidly unraveled the symbiosis that once underpinned US-China relations under neoliberal globalization. Contrary to popular narratives, the zero-sum rivalry between the two powers is not a civilizational clash. Rather, it is the culmination of decades of failed neoliberal policies that generated two interconnected forms of inequality: one within countries (where wealth became concentrated in the hands of a few) and another between countries (where the Global North entrenched its dominance over high-value industries while the Global South remained trapped in low-value production and resource extraction, bearing the brunt of ecological degradation and regional destabilization).4Jake Werner, A Program for Progressive China Policy: July 2024 | Quincy Brief No. 62 (Washington DC: Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, 2024), available at https://quincyinst.org/research/a-program-for-progressive-china-policy/#.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, widely seen as the clearest indication of neoliberalism’s deep imbalances, Beijing launched the world’s largest stimulus program, stabilizing global growth but exacerbating domestic problems of debt, overcapacity, and overproduction. To alleviate these pressures, Chinese companies expanded overseas under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which channeled excess industrial capacity into overseas infrastructure projects. At the same time, to escape the so-called middle-income trap, the Chinese state pursued industrial upgrading, encouraging companies to move up the global value chain. Backed by extensive state support and long-term planning, Chinese companies began capturing larger shares of international markets and challenging the dominance of the US and its allies in advanced industries.5Eli Friedman et al., China in Global Capitalism: Building International Solidarity Against Imperial Rivalry (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2024). Built on a vast labor force, modern infrastructure, and integrated industrial base, China’s success posed a direct threat to the profitability of US corporations, particularly in high-value sectors such as research, development, and advanced manufacturing.

Threatened by China’s rapid ascent, the perception in Washington shifted dramatically: what had once been seen as a mere byproduct of modernization and a boon to global science and innovation came to be recast as a deliberate strategy to erode US technological and geopolitical dominance.

With the rise of competitive Chinese industries, Washington—spurred by its national security establishment and its newly aligned corporate elites—shifted decisively toward economic warfare fusing economic policy with national security priorities.6No one illustrates this point better than Eric Schmidt. See “Eric Schmidt cozies up to China’s AI industry while warning the U.S. of its dangers,” Tech Transparency Project, April 11, 2024, https://www.techtransparencyproject.org/articles/eric-schmidt-cozies-up-to-chinas-ai-industry-while?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Leveraging control over critical nodes of the global economic system, Washington began deploying a wide array of coercive instruments, including sanctions, export controls, tariffs, and industrial policies designed to constrain China’s ascent.7Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, “The Weaponized World Economy: Surviving the Age of Economic Coercion,” Foreign Affairs, August 19, 2025. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/weaponized-world-economy-farrell-newman. The most securitized arenas of this new conflict include semiconductors, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, quantum computing, and advanced batteries. The sectors are now cast as the “industries of the future” upon which the preservation of US dominance is believed to hinge.82024 Report to Congress of the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission (Washington DC: U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2024), Chapter 3, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/Chapter_3–U.S.-China_Competition_in_Emerging_Technologies.pdf. These areas have become focal points of US state intervention aimed at preserving US dominance and excluding China from the technological frontier. Notable policy examples include the Trump administration’s crackdown on Huawei and the Biden administration’s CHIPS and Science Act.9Jill C. Gallagher, U.S. restrictions on Huawei Technologies: National Security and Policy Implications (Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022), available at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47012; “FACT SHEET: CHIPS and Science Act will lower costs, create jobs, strengthen supply chains, and counter China,” The White House, August 9, 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Anti-Chinese Hysteria in Academia

Because universities occupy the upstream end of the global value chain—where basic research, scientific discovery, and technological innovation begin—academia has become one of the most visible battlegrounds for US-China great power rivalry. The breakdown of cross-border intellectual exchange is inseparable from shifting perception of China’s ascent in science and technology in the US, cast not as mutually beneficial but as an existential threat to US national interests.

For three decades after the Cold War, neoliberal globalization encouraged the integration of Chinese society into global knowledge creation networks.10Tommy Shih and Caroline S. Wagner, “The Trap of Securitizing Science,” Issues in Science and Technology 41, no. 1, 100–03, https://doi.org/10.58875/ZSDO9141. Chinese universities entered joint ventures with American counterparts.11Qinyi Yin, “Even as Tensions Grow, U.S.–China Joint Venture Universities Have Room to Develop,” CSIS, September 6, 2023, https://www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/even-tensions-grow-us-china-joint-venture-universities-have-room. Language programs flourished as US universities chased international tuition revenue, and the number of Chinese students in the United States grew from roughly to over 370,000 by 2019 from 50,000 in 2000.12Shih and Wagner, “The Trap of Securitizing Science.” Collaborative research expanded just as rapidly. By 2022, China had become the United States’s largest research partner, accounting for nearly a quarter of all internationally coauthored US papers.13Benjamin Schneider, Jeffrey Alexander, and Patrick Thomas, Publications Output: U.S. Trends and International Comparisons (Alexandria, VA: National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics), available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb202333/. Formalized through bilateral agreements and sustained by voluntary networks often led by researchers of Chinese descent, these collaborations drew on the two countries’ complementary strengths and generated substantial scientific and economic gains for both sides.14Denis Simon and Caroline S. Wagner, U.S.–China Scientific Collaboration at a Crossroads: Navigating Strategic Engagement in the Era of Scientific Nationalism | Quincey Paper, no. 18, Nov 2025 (Washington DC: Quincy Institute, 2025), available at https://quincyinst.org/research/u-s-china-scientific-collaboration-at-a-crossroads-navigating-strategic-engagement-in-the-era-of-scientific-nationalism/#.

The United States’s active embrace of China’s integration into global knowledge networks rested on a familiar set of neoliberal assumptions: that integration would gradually help China “catch up” while nudging it toward liberal scientific norms and institutional models: openness, academic freedom, and scientific inquiry insulated from state directives; a view of cross-border flows of people and knowledge as inherently benign and mutually beneficial; and the ultimate reinforcement of US hegemony by China’s modernization through channeling talent and resources into American institutions. These premises positioned China’s rise as a complement to both the US-centered architecture of global science and technology and the broader liberal international order that sustained it.

Yet these assumptions began to unravel as China’s educational and research infrastructure matured, steadily eroding US dominance, especially in strategically critical and commercially lucrative technological areas.15Justin Riggi “How China Is Outperforming the United States in Critical Technologies,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, September 23, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/09/23/how-china-is-outperforming-the-united-states-in-critical-technologies/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. The scale of this transformation is striking. China produced 3.6 million STEM graduates in 2020, compared to just 820,000 in the United States. As a measure of research output, China’s share of global scientific publications rose from less than 2 percent in 1990 to roughly 25 percent in 2023. Researchers based in Chinese institutions now surpass their US counterparts in both the volume and, increasingly, the impact of work in key technological fields. Not surprisingly, by 2022 nearly half of all global patent filings originated from China.16Shih and Wagner, “The Trap of Securitizing Science.”

Similarly, the past decade has not pushed China toward scientific liberalization, market-driven innovation, or toward becoming “more like us.” Instead, China has deepened its commitment to a state-led R&D model. Central planners have not only picked out the right sectors and subsidized “national champions,” but also built the underlying infrastructure, cultivated dense innovation ecosystems, and developed a massive and highly skilled workforce to reduce dependence on the United States and hedge against geopolitical headwinds.17Dan Wang and Arthur Kroeber “The Real China Model: Beijing’s Enduring Formula for Wealth and Power,” Foreign Affairs, August 19, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/real-china-model-wang-kroeber.

Threatened by China’s rapid ascent, the perception in Washington shifted dramatically: what had once been seen as a mere byproduct of modernization and a boon to global science and innovation came to be recast as a deliberate strategy to erode US technological and geopolitical dominance.18Simon and Wagner, U.S.–China Scientific Collaboration at a Crossroads. This reframing began during President Obama’s second term and solidified with the first Trump administration’s 2017 US National Security Strategy (NSS), which explicitly labelled China as a “revisionist power” that “seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region.”19The National Security Strategy of the United States of America: December 2017 (Washington, DC: The White House, 2017), available at https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. The same NSS introduced the concept of the “National Security Innovation Base” (NSIB) as a core pillar of US security strategy, defining it as the American network of knowledge, capabilities, and people—including academia, national labs, and the private sector—that turns ideas into innovations and transforms discoveries into commercial applications. Within this framework, China’s technological rise was portrayed as an existential threat to American security and prosperity.

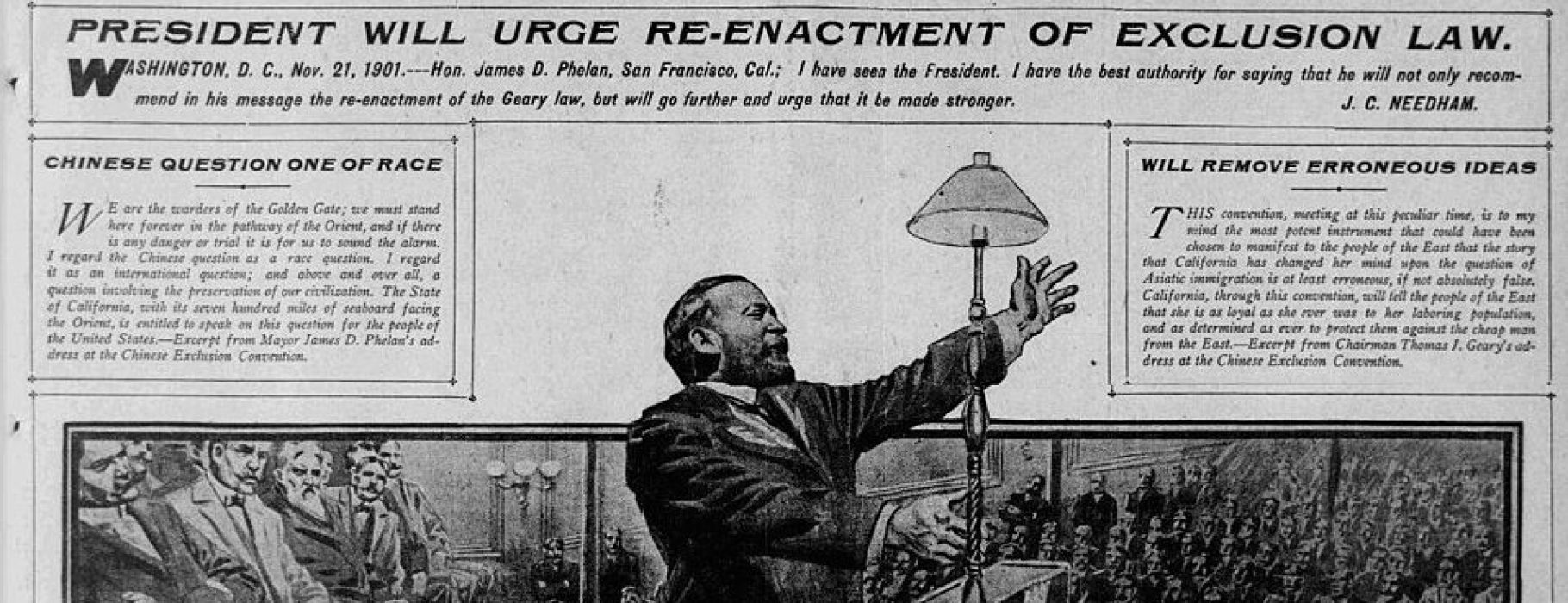

With national security elevated above all else, decades of scientific and educational collaboration have rapidly given way to an atmosphere of suspicion and control. Scholars, students, and institutions now navigate systems designed to police the very networks that once defined globalized academia. Individuals of Chinese descent, especially those with ties to both countries, are recast as tools of grand strategy: valued as assets, flagged as threats, or discarded as collateral. This dehumanization draws on long-standing racist tropes as “disloyal”, “deceitful”, and “perpetual foreigners”, unleashing levels of anti-Chinese hysteria unseen since the late 1800s.20Kiron Skinner, a contributor to Project 2025, claimed that China’s “internal culture and civil society will never deliver a more normative nation,” framing the conflict as uniquely destabilizing because China is “not Caucasian.” See Tara Francis Chan, “State Department official on China threat: for first time U.S. has ‘great power competitor that is not Caucasian,” Newsweek, May 6, 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/china-threat-state-department-race-caucasian-1413202. Even the Biden administration’s rhetoric–accusing China of “dumping,” “market distortions,” and “unfair practices”–revives familiar narratives of Chinese deceit to justify a new phase of economic containment. See this cartoon and the original Bloomberg article it references. Tweet by Jenny Chase (@solar_chase), X, May 14, 2024, 6:00 a.m., https://x.com/solar_chase/status/1790321227485106282; Josh Wingrove, Jennifer A Dlouhy, and Eric Martin, “Biden to hike tariffs on China EVs and offer solar exclusions,” Bloomberg, May 12, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-12/biden-s-china-tariffs-salvo-to-range-from-doubling-to-quadruple.

Universities, long champions of academic exchange under neoliberal globalization, have responded ambivalently…Declining enrollment of Chinese students threatens their financial model, yet investigations or grant suspensions threaten their research budgets. Confronted with these pressures, many administrations have opted for compliance rather than defense…

The securitization of academia and targeting of Chinese academics, especially in sensitive STEM disciplines, reached its most aggressive form with the China Initiative, launched in 2018 under the first Trump administration. The program marked an unprecedented expansion of federal surveillance into universities and research institutions, targeting scientists—particularly those of Chinese or other Asian descent—under suspicion of espionage or undisclosed foreign ties. Officials claimed the initiative aimed to develop “a coherent approach to the challenges posed” by the Chinese government, which allegedly deployed “businessmen, scientists, high-level academics, and graduate students” to conduct economic espionage and intellectual property theft.21Matthew Olsen, “Assistant Attorney General Matthew G. Olsen delivers remarks on countering nation-state threats,” (Speech, Washington DC, February 22, 2023), U.S. Department of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-matthew-olsen-delivers-remarks-countering-nation-state-threats; “FBI’s Christopher Wray testifies to Senate Judiciary Committee – watch live,” YouTube video, 3:14:34, posted by “Guardian News,” July 23, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ipifjhs7VLg. In practice, however, the program incentivized FBI agents and DOJ prosecutors to engage in racial profiling and pursue weak and often baseless cases. Many prosecutions had no connection to espionage. Instead, they revolved around minor administrative issues such as alleged nondisclosure of affiliations, visa irregularities, or tax discrepancies—matters previously handled through civil or other institutional channels.22Ashley Gorski and Patrick Toomey, “Protecting civil rights amid US-China competition,” in Getting China Right at Home: Addressing the Domestic Challenges of Intensifying Competition, ed. Jessica Chen Weiss (Washington DC: John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, 2025), 63–67, available at https://mediahost.sais-jhu.edu/saismedia/media/web/reports/assets/files/getting-china-right-at-home.pdf. The result was a pattern of criminalizing ordinary academic conduct and stigmatizing an entire community of scholars. The Biden administration formally dissolved the China Initiative in February 2022, following a DOJ strategic review that concluded the program had created a “harmful perception” of racial bias and a chilling effect on scientific research. Nonetheless, members of the MAGA wing in Congress have been repeatedly trying to reinstate it ever since.

Beyond targeting established scholars, the Trump administration extended its crackdown to Chinese graduate students through the 2020 Presidential Proclamation 10043. The order barred entry of graduate students and researchers affiliated with China’s “Military-Civil Fusion.”23Proclamation No. 10043, 85, Fed. Reg. 34353, (May 29, 2020), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/06/04/2020-12217/suspension-of-entry-as-nonimmigrants-of-certain-students-and-researchers-from-the-peoples-republic. As a result, the number of newly admitted Chinese graduate students in sensitive STEM fields fell sharply, from more than thirty thousand in the early 2010s to fewer than twenty thousand by 2023. Visa delays, denials, and revocations also disrupted the studies and research of many Chinese PhD candidates and postdoctoral scholars at US universities, forcing some to abandon their programs altogether.

As anti-China politics became a pillar of right-wing populism, MAGA governors and state legislators have taken upon themselves to implement their own versions of exclusionary measures targeting Chinese academics. For example, Florida Senate Bill 286 restricts public universities from entering partnerships or accepting grants from institutions in “countries of concern”—which include China, Iran, Russia, North Korea, Cuba, Syria, and Venezuela—without prior approval from the governing board. Senate Bill 846 goes further, prohibiting public universities from employing individuals or signing agreements with persons from these same countries unless explicitly authorized. Similarly, Ohio’s Higher Education Enhancement Act expands state oversight of higher education while imposing broad bans on research and financial relationships with Chinese institutions.

Compared to MAGA’s ostentatious revival of Chinese Exclusion Act-style politics, the Democratic establishment has pursued a quieter but equally consequential path, continuing—and in many cases doubling down on—the securitization and surveillance framework that underpins the strategy of protecting national security. For instance, the CHIPS and Science Act signed by President Biden in 2022 established federally funded Research Security Centers to train compliance officers, share threat intelligence with law enforcement, and standardize surveillance mechanisms across universities. Framed as measures to protect openness while safeguarding the integrity and security of federally funded R&D, these initiatives in practice embed intelligence structures within academia, transforming universities into extensions of the national security state.24U.S Executive Office of the President, “Memorandum for the Heads of Federal Research Agencies,” July 9, 2024, Office of Science and Technology Policy, available at https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/OSTP-RSP-Guidelines-Memo.pdf.

Eager to avoid accusations of racial bias, Democratic leaders often draw a rhetorical distinction between “the Chinese government” and “the Chinese people.” Yet their policies belie this supposed nuance. The DOJ has continued China-related investigations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has maintained secret internal probes into Chinese-linked researchers, and the State Department has sustained visa revocations and interrogations under Proclamation 10043.25Jeffrey Mervis, “Pall of suspicion: the National Institutes of Health’s ‘China Initiative’ has upended hundreds of lives and academic careers,” Science, March 23, 2023, https://www.science.org/content/article/pall-suspicion-nihs-secretive-china-initiative-destroyed-scores-academic-careers; Amy Hawkins, “Chinese students in US tell of ‘chilling’ interrogations and deportations,” Guardian, April 20, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/apr/20/chinese-students-in-us-tell-of-chilling-interrogations-and-deportations. Meanwhile, FBI Director Christopher Wray, retained by the Biden administration, reaffirmed in a 2023 speech at Texas A&M University that “there is no doubt that the greatest long-term threat to our nation’s ideas, our economic security, and our national security is posed by the Chinese Communist government,” immediately followed by the familiar disclaimer that “to be clear, that threat stems from the Chinese government, not the Chinese people.” Yet moments later, Wray warned that the “current Chinese regime will stop at nothing to steal what they can’t create and silence the messages they don’t want to hear, all in an effort to surpass us as a global superpower.” Despite his qualification, the speech ultimately reinforced the notion of the “China threat” as a “whole of society threat,” and, by extension, the need for a “whole of society response.”26Open Hearing on Worldwide Threats: Hearing Before the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, 115th Cong. 2 (2018), available at http://intelligence.senate.gov/hearings/open-hearing-worldwide-threats-0. In practice, such rhetoric blurs the line between the Chinese government and Chinese people.

Universities, long champions of academic exchange under neoliberal globalization, have responded ambivalently. As these neoliberal institutions depend on tuition revenue and federal research funding, they are torn between competing priorities. Declining enrollment of Chinese students threatens their financial model, yet investigations or grant suspensions threaten their research budgets. Confronted with these pressures, many administrations have opted for compliance rather than defense, cooperating closely with federal agencies while offering minimal support to targeted faculty or students.27Valentina Dallona and Rose Ying, “Chinese Students and Scholars Faced Targeting Before Trump. Now It’s Escalating,” Truthout, April 18, 2025, https://truthout.org/articles/chinese-students-and-scholars-faced-targeting-before-trump-now-its-escalating/. For instance, 44 percent of the 255 professors the NIH pressured universities to investigate lost their positions, most of them tenured. The NIH warned that unresolved concerns could lead to grant repayments or trigger audits of an institution’s entire NIH portfolio.28Lele Sang, “US universities secretly turned their back on Chinese professors under DOJ’s China Initiative,” Ford School of Public Policy, March 29, 2024, https://fordschool.umich.edu/news/2024/us-universities-secretly-turned-their-back-chinese-professors-under-dojs-china-initiative?utm_source=chatgpt.comhttps://fordschool.umich.edu/news/2024/us-universities-secretly-turned-their-back-chinese-professors-under-dojs-china-initiative?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Fearing such repercussions, universities often urged the accused faculty to resign or retire quietly, effectively prioritizing institutional self-protection over academic freedom and due process.29Kimmy Yam, “After scientist questioned for China ties died by suicide, family sues and speaks out,” NBC News, July 12, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/northwestern-jane-wu-lab-suicide-lawsuit-rcna217636.

Path Forward

US progressives must reject the logic of great power conflict that casts the United States and China as inevitable rivals on a path toward an open-ended global conflict. Such a conflict would only further empower authoritarians, militarists, and nationalists who thrive on fear and “othering”—mobilizing “our” people against “their” people while silencing dissent within “our” own ranks. Under Trump 2.0, this logic has hardened into a revived McCarthyism in higher education marked by intensified surveillance, ideological policing, and a broad attack on universities as alleged centers of foreign influence and domestic subversion.

Building solidarity with Chinese students, researchers, and scholars on campus is a concrete way to reject the notion that security and opportunity can only be achieved through zero-sum competition across racial, ethnic, and national lines. It is also a step toward reclaiming higher education from the neoliberal logics that have hollowed it out, reaffirming universities as a democratic public good rather than a site for asset management, national domination, or revenue extraction. Crucially, this struggle is about altering power relations within the university itself, away from administrations, provosts, and boards of trustees that govern through risk management and political appeasement and toward the students, faculty, and staff whose collective labor makes the university function.

For decades, major US labor leaders portrayed China as an economic scapegoat responsible for job loss and deindustrialization, reinforcing nationalist and protectionist narratives that mirror the state’s securitized zero-sum worldview. Breaking from this legacy requires a new internationalism rooted in shared struggle in place of great power competition.

Given the stakes, our strategy must operate on two levels: locally, by challenging university administrations, and through cross-campus coordination that can alter the political landscape and institutions that sustain zero-sum conflict and normalize the logic of securitization. Above all, these efforts must be invested for the long haul, shifting from short-term, reactive mobilization to deep, sustained organizing capable of changing structural relationships over time.

So far, the treatment of Chinese students and scholars has remained a marginal issue, eclipsed by other campus struggles. This is true even before the assaults on higher education under the current Trump administration. Past campaigns, such as those opposing the revival of the “China Initiative” and similar efforts opposing the exclusion of Chinese academics at the state level for instance, have relied heavily on small circles of professional advocates within few national nonprofits or academic associations. These efforts often hinge on persuading those in power that Chinese and other Asian communities have been unfairly targeted, rather than building collective power from below. The result of these efforts is that movements end up giving Democratic Party’s “virtue signaling” a free pass and allowing them to posture as defenders of diversity and inclusion even as they expand the national security state. Moreover, these efforts lack the explicit aim and strategy of altering the power relationship between those that capitalize on the conflict and those that resist it. Additionally, top-down mobilizations, no matter how well intentioned, rarely cultivate a durable base capable of sustained struggle. Without an organized, continuously engaged constituency, these issues rise and fall with the news and legislative cycles and even the most dedicated activists are forced to turn their attention elsewhere.

Organizing, by comparison, places the agency for success with a continually expanding base of ordinary people—a mass of people never previously involved, who had never thought of themselves as activists at all. And the main goal of organizing is the transfer of power from the elite to the rest of us.30Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190624712.001.0001.

Among the many forms of campus organizing and resistance, the one that’s led by academic unions offer one of the most promising paths forward. Academic unions of faculty and graduate student employees are now the fastest-growing sector of US organized labor. They have led some of the most transformative fights against the neoliberalization of higher education and in defense of academic freedom. Academic organizers are increasingly coordinating across different job categories and across institutions and regions, drawing inspiration from industrial-style labor organizing as exemplified by networks such as Higher Education Labor United (HELU) and Long-Haul.31Ian Gavigan and Jennifer Mittelstadt, “A New Deal for Eds and Meds,” Dissent, Fall, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1353/dss.2021.0100; “Homepage,” Higher Ed Labor United, accessed January 17, 2026, https://higheredlaborunited.org/; “An Intervention on the Response of Campus Labor to the Federal Funding Freezes,” Long Haul, May 14, 2025, https://longhaulmag.com/2025/05/14/response-campus-labor/. Building on this growing infrastructure of coordination, our team at Justice is Global recently mobilized against the Select Committee on CCP’s demand for information on Chinese student enrollment from six universities, while continuing to support on-the-ground organizing as university administrations increasingly cave to political pressure.32“Academic Workers Letter on Protection of Chinese and All International Members of Our Campus Communities,” Google Forms, accessed January 17, 2026, https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScT4i-ckP2Er0iePCmAnKQ4QJ6i2mEqbf9f0bH3uAX-O_biLA/viewform; Seth Nelson, “Purdue effectively bans grad students from China, other countries faculty say,” Journal and Courier, December 3, 2025, https://www.jconline.com/story/news/local/purdue/2025/12/03/purdue-grad-students-from-5-countries-unlikely-to-be-admitted-china-russia-iran-cuba-north-korea/87583768007/.

Many inside and outside organized labor see strong, independent, and democratic unions as the best safeguard against tyranny. Such unions understand that the targeting of Chinese students and scholars is not a peripheral issue but a classic ploy of bosses and the state to divide and weaken the working class. What’s at stake is fundamentally a labor issue: who controls our work, and for whose purpose? Today’s neoliberal universities, run like corporations, elevate “top talent” for their profitability while rendering everyone else disposable. The same logic that turns knowledge creation into a tool for world dominance also rationalizes surveillance and repression of free thought in the name of “national security.” True solidarity demands the rejection of this logic, the defense of human dignity, the refusal of the security for the few at the expense of the many, and the assertion of our freedom to work and think without fear or harassment.

Independent and democratic unions would also confront US labor’s own history of Sinophobia. For decades, major US labor leaders portrayed China as an economic scapegoat responsible for job loss and deindustrialization, reinforcing nationalist and protectionist narratives that mirror the state’s securitized zero-sum worldview.33Promise Li, “Labor has a China problem—but not the one you think,” Nation, April 16, 2025, https://www.thenation.com/article/economy/american-labor-anti-china-racism/. Breaking from this legacy requires a new internationalism rooted in shared struggle in place of great power competition.

Building solidarity with Chinese students and scholars, and welcoming them to union ranks, are vital to this new internationalism. Despite declining numbers in recent years, driven primarily by anti-Chinese hysteria outlined above, students and scholars from China continue to make up a substantial share of the academic workforce. Too often stereotyped as wealthy, apolitical, or isolated, they have historically been marginalized within academic unions.34Promise Li et al., “Organizing from below: Chinese international student workers and the UC Strike,” Lausan Collective, January 31, 2023 https://lausancollective.com/2023/chinese-student-workers-uc-strike/. But this is changing. A growing number of Chinese international student organizers are taking on leadership roles within their union locals, shaping the political consciousness of their peers and helping to bridge unions and their largely unengaged Chinese membership.35Friedman et al., China in Global Capitalism.

Chinese international students have been actively involved in major campaigns such as the 2022 University of California system strike, the 2023 University of Michigan strike, and recent pro-Palestine solidarity encampments.36UMich GEO, “2023 UMich GEO 罢工全记录”, Weixin, January 23, 2024, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/pkejCM3Rz0W8EE6-6qHfHg. Despite facing surveillance and political pressure from both US and Chinese authorities, many Chinese graduate workers have come to see collective labor action as one of the few viable avenues for campus activism. To build on this momentum, unions must intentionally cultivate leaders from these communities, empowering them to shape their locals’ agendas and campaigns. They can also help these leaders to communicate “union vernacular” in accessible ways to their Chinese peers, develop Chinese-language information sharing networks, and address their grievances around transparency and inclusion in union spaces.37“Home Page”, Academic Union Network, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://zh.academic-union-network.org/; Li, “Organizing from Below.”

The ties forged between the US labor movement and Chinese international students also hold transformative potential beyond academia. Many of these students will return to China, where academics and workers face mounting authoritarian repression, exacerbated by great power conflict and the growing influence of US-style privatization in higher education.38Joyce Jiang, “Targeted abroad and shunned at home: Chinese overseas students caught in limbo,” CNN, September 12, 2025, updated September 13, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/09/12/china/china-us-students-golden-ticket-hnk-intl;Yuxuan Jia and Zhong Huiqing, “Big science, Chinese style: BGI’s Mei Yonghong on Reshaping the Research Paradigm from Govt Grant-guzzling to Profit-making Businesses,” Pekingnology (substack), September 9, 2025, https://www.pekingnology.com/p/big-science-chinese-style-bgis-mei. The organizing experience and solidarity they gain within US unions can seed new forms of collective resistance, linking struggles against repression and commodification of human life across national boundaries. These cross-border connections could lay the groundwork for a renewed internationalism rooted in solidarity and interdependence—one that is capable of confronting shared global challenges and rebuilding a global economy on stronger footings. From fighting climate change and preparing for future pandemics to regulating artificial intelligence, human security and other public goods risk being subordinated to profit imperatives and national security dictates. Building these ties today is therefore not only an act of resistance to great power conflict and the authoritarian offensive, but also a commitment to the long-term project of collective liberation.