The opening scene features a man in a street, hypersensitive to his surroundings. He is waiting to place a bomb in a storeroom of the factory where he works in Algiers. Insufferable drips of rain refuse to build into a downpour. The man is Fernand Iveton, and the year is 1956.

The car he is waiting for finally arrives, and Fernand is given a bomb in a shoebox with a timer set to the agreed time, all of which he carefully places in a sports bag. He has been returning from his breaks with the bag slung over his shoulder for a few consecutive days, to accustom the foreman and security guards to his behavior.

Fernand successfully places the bomb in the disused storeroom – selected to ensure no one would die in the blast – and returns to his work-station. A group of cops descend on him almost immediately. The factory foreman smirks in the background. If not the snitch himself, he’s at least a happy beneficiary. Fernand is thrown into a van and taken to Algiers central police station. On the way, it’s made clear what awaits him on arrival:

:

We know who you are, Iveton, we’ve got files on you, you communist fuck, you won’t be so high and mighty anymore with your little kisser, Iveton, your little Arab mustache, you’ll see, we’re going to make you talk at the station, you better believe it, we’re talented we are, we always get our way, and believe me we’re going to do whatever the fuck we want with your piece of shit communist mouth, we could force a mute to belt out an opera.

Torture as biological debasement, as the animalization of the victim, ensues unrelentingly over several pages. He is kicked and punched. Stripped naked. His limbs are bound. He is blindfolded. Electrodes are placed on his neck; later, on his testicles. Then the rest of his body. He is burned all over with electric currents, as one officer operates the generator, and others manipulate his limbs. He is placed on a bench. No longer able to control his muscles, his head hangs backwards, suspended in the air. A cloth is placed over his face. Water is made to flow and flow, swelling his stomach and suffocating his lungs. He loses consciousness and is slapped awake. He is reduced to his body, which he fears will ultimately be unfaithful. “Fernand shivers. He is ashamed of how little control he has over his body. His own body, which could betray, abandon, sell him to the enemy.” His singular aim is to hang on at least long enough for his comrades to hide, before inevitably giving his tormentors a couple of names, once his body fails, and nothing matters except an end to the pain.

Glimpses of the wider scenario are introduced in pockets. Algiers is in a heightened state of agitation. The Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), commencing their war of liberation in 1954, have escalated attacks – a couple of months earlier the Milk Bar and La Cafétéria were bombed to ruins, and just two days prior to Fernand’s interrupted attempt at the factory, explosions rocked a tram station, a supermarket, a bus, a train, and two cafés. The French security apparatus has its military vehicles crawling the streets, but the language of colonial order refuses the notion that a war has started; instead, it is merely a series of events. Later, counter-insurgency rages in the backcountry, but “still no war, no, no that. Power minds its language – its fatigues tailored from satin, its butchery smothered by propriety.”

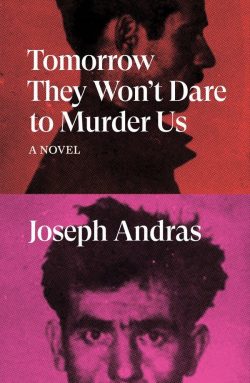

Joseph Andras’s Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us is a compact, fictionalized account of events leading up to the guillotining of Fernand Iveton on February 11, 1957 – the only beheading of a “European” by the French state during the Algerian War. Chapter by chapter, the novel shifts between two parallel tracks and temporalities until their late merger in the closing passages.

The first narrative line, punctuated with sharp sentences and a palpable sense of acceleration, charts the arc of Iveton’s experience from the suspended factory bombing of November 1956 to his death at the hands of colonial administrators.

A second thread, languid in pacing, and more capacious in the structure of its prose, begins further back in time, crossing between Algiers and the French village of Annet, and back again, then from the Algerian countryside to Paris. It contains the love story of Fernand – born and raised in Algeria, to a French father who was a member of the Algerian Communist Party, and a Spanish mother who died when he was two – and Hélène – born in a Polish village to a poor father who played the violin, and a wealthy mother who turned her back on her class. The family migrated to France and became agricultural labourers.

By day, Hélène works in a tannery in the village of Langy, and by night, in Café Bleu in Annet, making appetizers and desserts. She meets Fernand in the café, which is nearby to the family pension where he is riding out a tubercular convalescence. If in the claustrophobic prison cells and torture chambers Fernand’s body is broken down and alienated from his mastery through the crude tools of colonial machinery, the story of early love is marked by a slower pace of quotidian human experience, including a different sort of corporeal abandon, this time ecstatic, libidinal. Take, for instance, Fernand and Hélène’s first sexual encounter – “moist tangle of tongues,” “braid of legs on the rough cotton” – when Fernand shakes to the point of trembling, and “doubts the reality of what he is currently experiencing.”

Brisk empiricism in the first storyline bridges later to extended, dialogical scenes pivoting on Fernand’s prison comradeship with his Arab cellmates. Lethargic, early passages of the second, meanwhile, gradually assimilate a sense of urgency as the novel progresses, and as the locales shift from France to Algeria. The gravity of Fernand’s death sentence sets more firmly into reality.

In equal measure an accounting of the enormous objective forces unfolding a colonial nightmare across the Mediterranean from France, and a portrayal of the depths of characters’ intimate subjectivities – themselves imbricated with and mediating the parts of that social whole – Andras’s novel reaches for imaginative inner connections and syntheses across scale and time. He is no stranger to sociological contradiction, nor to psychological complexity. His fiction never reduces to a merely didactic idiom. At the same time, Andras circumnavigates, and at a wide berth, the varied formulae of literary liberal-humanism, whether it be the sentimental humanitarian mode, or, alternatively, the mode of moral pragmaticism and apoliticism attached to certain expressions of ironical cynicism. (“Irony can be a numbing response to political and cultural malaise,” Christian Lorentzen points out in a provocative survey of American literature in the latest Bookforum, “but it can also be a form of defiance born of rage and pain.” I refer here to the first of his two ironic sensibilities). The anti-colonial alignment of the novel is unadulterated.