In his Jacobin article entitled “Robert Brenner’s Unprofitable Theory of Global Stagnation,” Seth Ackerman rejects the view that revolution in the US (or elsewhere) is necessary to establish socialism and make things permanently better for all.1I would like to thank the invaluable contributions and comments provided by Marxist economists Brian Green, Murray E.G. Smith, and Lefteris Tsoulfidis in the drafting of this reply. Instead, he believes that, by enacting a series of reforms, capitalism can be made into a more egalitarian and crisis-free system that will gradually move towards socialism.

In defense of his thesis, Ackerman seeks to refute the theory of secular stagnation in modern capitalist economies that the Marxist economic historian Robert Brenner has proposed over the last few decades. Ackerman argues that Brenner’s theory “is logically dubious and doesn’t fit the facts.” And so “the politics that flow from Brenner’s thesis becomes the biggest problem,” because it rules out the efficacy of any reforms under capitalism in helping people and gradually transitioning to socialism and, instead offers only the drastic alternative of revolution.

Let’s put to the side the red herring that revolutionaries counter-pose reform to revolution. Any serious revolutionary does not do so, but instead sees winning reforms as paving the way to revolution.

That stated, my reply is not centered on Brenner’s particular theory of long-term capitalist stagnation over the last 50 years. Ackerman says that Brenner’s theory is “increasingly influential.” But is it really? In fact, most Marxist economists who take the question of profitability seriously have criticized his stagnation thesis and the causes he gives for it.

They have moved on to a much better explanation of capitalist economies over the last 50 years. To be clear, I do not agree with Brenner’s theory for many reasons, which will become obvious below. My main concern is that Ackerman uses Brenner’s theory to trash Marxist economic theory in general and, in particular, Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (LTRPF) which Ackerman calls FROP (falling rate of profit).

Forgetting FROP

For Ackerman, the law of the FROP is neither valid nor relevant in explaining regular and recurring crises in modern capitalist economies. Ackerman reckons that “fundamentalist” Marxist economists are obsessed with profitability as the main cause of crises in modern economies as well as with searching for a theory of regular and recurring crises. For Ackerman, there are no regular and recurring crises, and they are not explained by changes in the profitability of capital.

This is a strange argument to make about modern market economies, where the profits of companies are regularly reported and financial investors make decisions on whether companies are doing well or not, based on measures of their earnings and future earnings prospects. Isn’t profit what capitalism is all about?

It is also strange to argue that Marxist “revolutionaries” are wrong in having “so much riding on their contention that extended periods of crisis are built into capitalism.” Has Ackerman not noticed that according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, there have been 33 such recessions in the US economy since 1857?

Crises under capitalism may or may not be “extended” or “secular,” as Brenner argues, but they are certainly a regular and recurring feature of “business cycles” that even neoclassical economists accept. Should we not look for explanations for these crises that relate to what is, after all, a profit-driven mode of production?

Ackerman says that, because “revolutionary Marxists” are so desperate to show that reforms and reformism won’t work, they need a theory of crises that can prove it. So, “by a process of ideological self-selection, the FROP came to be, as the late Simon Clarke put it in his study of Marxist crisis theory, ‘associated politically with a sectarian millenarianism’ that was becoming increasingly conspicuous in certain ultramontane sectors of the shrinking post-’60s Marxist left.”

Apparently FROP is a theory only promoted by sectarians in the labor movement. If so, then Marx must have been the first sectarian to “self-select” the theory.

Ackerman says that “To this day, in fact, it’s widely assumed that the FROP has always been the orthodox Marxist theory of crisis…. But the truth is almost the opposite: in the eight decades between Friedrich Engels’s death and the OPEC oil shocks, the FROP played almost no role in the various crisis theories of most leading Marxist authorities.”

Well, no and yes. I don’t think that even now FROP has been adopted by the majority of those claiming to be Marxists as their theory of crisis—I can cite many leading Marxists who reject it (and Ackerman has cited some too). Indeed, as Ackerman says, between the publication of Capital Volume 3 in 1894 and right up to the 1970s, FROP “played almost no role.”

Leading “classical” Marxists like Kautsky, Luxemburg, Hilferding, and Lenin either largely ignored the law or expressly dismissed it as irrelevant to crises under capitalism. There were exceptions. An obscure Bolshevik economist Miran Nakhimson criticized Luxemburg for ignoring its role in crises. He received short shrift from her. Another and most important exception was Henryk Grossman, who in the 1920s first developed a comprehensive explanation of the law of FROP and its role in precipitating crises.

Ackerman is correct that it was only in the 1970s and 1980s that FROP gained more traction among Marxist economists. But there was a very good reason for that: by every available statistical measure it had become clear that the profitability of capital had taken a huge dive from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.

And this crisis of profitability coincided with the first major post-war international recession of 1974-5 and then the deep slump of 1980-2. In my view, it was these events that revived interest in FROP in Marxist economic theory, not some desperate desire of sectarians to find a theory that rejected the possibility of reforms within capitalism.

Dropping FROP

Ah, but wait a moment. Ackerman says that FROP was not really Marx’s theory of crises at all. “There’s even good reason to doubt Marx’s own commitment to the idea. Clearly the FROP was a theory Marx wanted to believe was true. Just as physicists and mathematicians have been known to hope that an especially elegant theory or theorem will end up being confirmed by a future proof or experiment, Marx wanted to find a way to make the FROP work because, within the context of his theory, it led, as Duncan Foley put it, to ‘a beautiful dialectical denouement’.”

By every available statistical measure it had become clear that the profitability of capital had taken a huge dive from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.

Here Ackerman delves into the mind of Marx, arguing that Marx did not develop the theory scientifically, but because he needed it as a psychological prop to justify revolution. And yet in the same breath, Ackerman says that “Marx was a scrupulous scholar, and every time he tried to work out the details of the concept in his notes and drafts of the 1850s and 1860s, he found himself—as the German Marxologist Michael Heinrich has shown—lost in a maze of algebra that could only prove that a falling profit rate was a possibility, not a necessary outcome of capitalist development.” So, Marx was scrupulous in trying to develop FROP after all, even if he was lost in the algebra.

This brings us to the nonsense parroted by Ackerman from Michael Heinrich and others, namely that Marx eventually realized that the law of FROP did not work and so he dropped it in the 1870s. Ackerman quotes Simon Clarke: “Perhaps the best indication of the importance that Marx attached to the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is that he did not mention it in any of the works published in his lifetime, nor did he give it any further consideration in the twenty years of his life that followed the writing of the manuscript on which Volume Three of Capital is based.”

Moreover, as Paul Sweezy and Heinrich argue, the law of FROP was not logically valid but “indeterminate.” Ackerman quotes Sweezy that Marx’s analysis in that section was “neither systematic nor exhaustive” and “like so much else in Volume III it was left in an unfinished state.” Indeed, it was all Fred Engels’ fault for incorporating this rubbish about FROP into the third volume of Capital.

These are hoary old arguments that have been refuted by many scholars, something which Ackerman studiously fails to mention. First, there is no evidence that Marx dropped FROP; no remark and no reference, just surmise. Many scholars have pointed out that, if that were the case, he would have made it clear to Engels.

Instead in the 1870s, Marx continued to analyze the implications of the law, as Engels explains in his 1894 preface to Capital Volume 3. Indeed, Engels also contributed a special chapter on turnover and the rate of profit to Volume 3, something he had discussed with Marx many years earlier.

As for the law being “indeterminate,” this argument of Sweezy and Heinrich has also been refuted convincingly, in my view, by many Marxist authors since.2Here are just a few: Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts, “A Critique of Heinrich’s, ‘Crisis Theory, the Law of the Tendency of the Profit Rate to Fall, and Marx’s Studies in the 1870s’;” Andrew Kliman, Alan Freeman, Nick Potts, Alexey Gusev, and Brendan Cooney, “The Unmaking of Marx’s Capital: Heinrich’s Attempt to Eliminate Marx’s Crisis Theory;” Shane Mage, “Response to Heinrich—In Defense of Marx’s Law;” Fred Mosley, “Critique of Heinrich: Marx did not Abandon the Logical Structure.” Once again Ackerman fails to mention this.

It is not possible here to go into detail why Marx’s law of FROP is perfectly logical and fully determinate. But it starts with Marx’s law of value: the proposition that all value embodied in commodities produced for sale and purchase derives from human labor time.

So, if the human labor time expended falls relative to any rise in the contribution of non-human means of production (machines) to the production process, the result is a rise in what Marx called the “organic composition of capital” and thus a tendency for the overall profitability of capital invested (in both means of production and labor power) to fall. But this is a tendency that co-exists with counter-tendencies that can slow or reverse any decline for some time.

Eventually, however, the profit rate will resume its fall. The rate of profit will fall because the counter-tendencies are not sufficient to stop it. If Marx’s law of value is valid, then the law of FROP follows logically and is eminently determinate. But Ackerman ignores Marx’s law of value—probably because he rejects that too.

Okishio versus Marx

To continue his attack on FROP, Ackerman resurrects the Okishio theorem, the main theoretical weapon of the past used by FROP’s critics to reject the logical validity of Marx’s law.3Nobuo Okishio, “Technical Change and the Rate of Profit”, Kobe University Economic Review, 7, 1961, 85–99. Ackerman is impressed by the “mathematically forbidding Okishio Theorem,” which, he argues, “was a key reason — alongside the unavailing arguments of the FROP’s most dogmatic believers [Ackerman’s emphasis]— for the falling-profit-rate theory’s descent into disrepute. Because of it, many scholars broadly aligned with Marxism became persuaded that the theory had been definitively, scientifically discredited.”

Nobuo Okishio, a Japanese Marxist economist, argued that under competitive capitalism, a profit-maximizing individual capitalist will only adopt a new technique of production if it reduces the production cost per unit or increases profits per unit at going prices. So capitalist accumulation must lead to a rise in the rate of profit – otherwise why would any capitalist invest in new technology?

Ackerman relies on Anwar Shaikh, the prominent Marxist (classical) economist for an answer to Okishio’s theorem, an answer “which it must be said is ingenious.”4Anwar Shaikh, “Political economy and capitalism: notes on Dobb’s theory of crisis,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 2, No. 2 (June 1978), 233-251. According to Ackerman, orthodox as he might be, Shaikh is also “a scholar’s scholar, not a blinkered doctrinaire.” Actually, Shaikh’s refutation of Okishio is not the most convincing and a battery of other refutations are much more so.

Actually, the competition hypothesis for the FROP is not Marx’s, but that of Adam Smith.

Kliman, Moseley, and yours truly, among others, have shown that the Okishio theorem assumes something that is impossible in the real world: simultaneity of all capitalist decisions on investment and a process that allows benefits of one innovating capitalist to benefit them all.5Alan Freeman, “A general refutation of Okishio’s theorem and a proof of the falling rate of profit;” Andrew Kliman, “The Okishio Theorem: An Obituary;” Alan Freeman, “Price, value, and profit—a continuous general treatment;” Michael Roberts, “The fallacy of composition and the law of profitability.” Indeed, Okishio was later at pains to argue that his theorem was never intended as a refutation of Marx’s law of FROP at all.

Smith versus Marx

Having paraded Shaikh as a scholar’s scholar among a slew of Marxist doctrinaires, Ackerman then proceeds to attack Shaikh’s particular theory of competition under capitalism, which, he claims, reckons that competition among capitalists is aimed at cutting costs through price reductions. Ackerman argues that this is clearly wrong, as capitalists try to avoid price wars that are damaging to profits (and so, contrary to the main thrust of his argumentation, profits matter after all!).

Shaikh can speak for himself on this, but I don’t think Ackerman is right about Shaikh’s view of competition. In my view, competition among capitalists aims at increasing profit through reducing costs via better technology and labor-shedding, thereby yielding above-average profits.

The market price is not usually under the control of any individual capitalist company, so price cutting is not the main weapon of competition, but cost cutting is. Price cutting can increase market share; cost cutting increases profit margins per unit sold.

Ackerman reckons that companies do not compete on price but instead by making their products different from their rivals, through branding for example. But how exactly can product differentiation and related marketing tactics be seen as a “weapon against competition?” It seems to me that this has always been a weapon of competition.

But why this discussion of competition? Well, Ackerman wants to reject the two main factors that he identifies as central to Marxist FROP theories. The first is Marx’s own “rising organic composition of capital,” i.e., the increased investment in technology and machines relative to labor, which eventually reduces the increase in new value produced relative to the value of the stock of capital invested (see above).

The second factor concerns how competition among capitalist firms forces down prices and thus profits. It is this issue that brings us back to Brenner (remember him?). For it is Brenner who argues that the FROP operates through intensified price competition, not through a rising organic composition of capital mechanism.

Actually, the competition hypothesis for the FROP is not Marx’s, but that of Adam Smith, who also accepted FROP as a real and recurrent phenomenon. Marx criticized Smith’s explanation of FROP; but because Brenner accepts that the Okishio theorem refutes Marx’s own theory of FROP, he embraces a “neo-Smithian” theory of capitalist crisis.

Growth or stagnation?

Having dealt with the apparent logical faults in Marx’s law of FROP, Ackerman tells us that “the most serious problems with the thesis are empirical, not theoretical.” First, he argues that there has been no “long secular stagnation” in the world economy since the 1970s—which he says is Brenner’s thesis. With this, I agree.

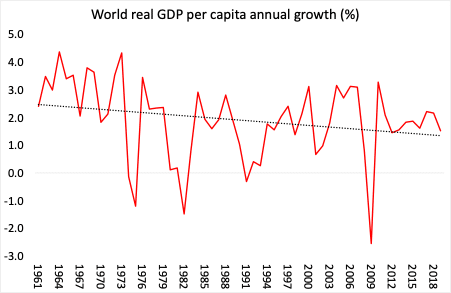

But his graph on world per capita real GDP growth is misleading. It purports to show that global economic growth has been above its long-term average since the 1970s, hence no stagnation. To claim this, Ackerman does a 25-year moving average of per capita real GDP growth—a peculiar measure. But let’s look at the official annual data first.

From this alone, we can see a downward trend in the growth in world real GDP per person going back to the 1960s. So, it turns out that Brenner’s case for secular stagnation, at least in the advanced capitalist economies, has some credibility, even if his explanations are wrong.

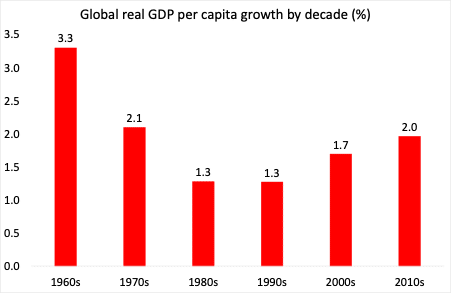

Next, let’s take the data decade by decade. Here we find that the 1980s and 1990s were not so great for growth, something that Ackerman’s own graph also shows if you look closely. But what about the 21st century? Why the improved growth rates in these two decades?

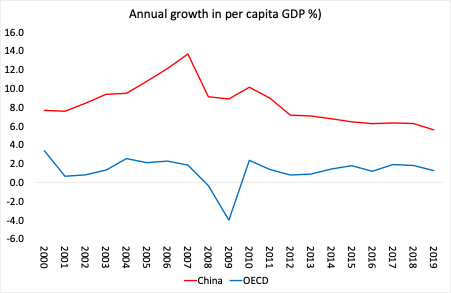

A huge part of the answer lies with the phenomenal growth in China (and to a much lesser extent in India). Strip China alone out of the equation and the global growth rate is much lower. Indeed, the OECD countries, the most advanced capitalist economies, have recorded very low growth rates in the 21st century.

In the 2000s, China’s per capita growth averaged 9.8 percent while the OECD could only manage 1.0 percent a year. In the 2010s, a decade that I have called the Long Depression, China achieved an average per capita growth rate of 7.1 percent, while the OECD managed only 1.5 percent.

Mirage or reality?

Now you would expect a falling real GDP growth rate to be associated with a falling investment growth rate and behind that, if Marx’s FROP theory is empirically valid, a falling FROP since the 1960s, even if there are periods of rising profitability. All the empirical evidence compiled by many Marxist economists (and I might add, by many mainstream economists) confirms this.6Carchedi and Roberts, World in Crisis (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018). For mainstream economic support see Reserve Bank of Cleveland, https://www.clevelandfed.org/publications/economic-commentary/2016/ec-201609-recession-probabilities. J Tapia, “Investment, profits and crises – theories and evidence,” in Carchedi and Roberts, World in Crisis 2018. Ascension Mejorado and Manuel Roman, Profitability and the Great Recession (New York, Routledge, 2014). None of this scholarly work is cited by Ackerman.

None of this scholarly work is cited by Ackerman.

But Ackerman is determined to refute this empirical support for FROP. His main argument is that the official sources for measuring the US rate of profit, or for the world economy for that matter, are faulty. When corrected, as he purports to have done, the US rate of profit is shown to be rising since the 1980s, not falling. So FROP is a “statistical mirage.”

Let’s remind ourselves of Marx’s basic formula for the rate of profit in a capitalist economy. The rate of profit (r) is s/(c + v), where s is what Marx calls surplus value (but for present purposes call it total profits); c is the value of the stock (not flow) of all means of production (machinery and raw materials) measured in money (called constant capital by Marx); and v is the wages and other benefits paid to employees.

Many Marxist economists exclude v from the rate of profit equation because wages are not a large component of the bottom line compared to the stock of capital built up over decades. And raw materials and inventories are excluded because they are also small relative to the stock of fixed assets (plant, machinery, etc.). So, the rate of profit then becomes total profits divided by the value of the stock of fixed assets (s/c).

But the money value of the stock of capital does not stay the same year after year; there are new investments or additions to the stocks and some of the stock depreciates in value as it has a limited life-span, or it becomes obsolescete and is replaced by new technologies. So, the total stock of fixed assets capital relies on must be adjusted for depreciation in each production period (year).

Here is where Ackerman delivers what he thinks is his decisive blow to FROP theory. He argues that the official US data on depreciation of fixed assets are gross underestimates: “As it happens, new research published separately by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has confirmed long-standing suspicions about even the approximate accuracy of official capital stock estimates.”

He notes that the OECD “systematically compares the methods used for estimating capital stocks in the United States, Canada, the UK, France, Germany, and Italy,” and concludes that in all five non-US countries, depreciation estimates are “higher, or much higher, than those used in the United States.” Adopting other countries’ statistical methods would “reduce the net investment rate and the net capital stock of the US private sector by up to one third” — which would, of course, have a big upward effect on measured profit rates.”

Ackerman concludes: “Whereas the net profit rate for the business sector implied by published US capital stock estimates stagnates in the 18 to 20 percent range throughout the period since 1985, the alternative estimates using Canadian depreciation patterns show US profit rates doubling, or nearly so: rising from 16 percent in the late 1980s to 28 percent or 32 percent in the pre-pandemic years.” On this, see his Chart 4 in his article.

But hold your horses! As the Monthly Labor Review article relied on for these depreciation methods points out: “Depreciation rates from another country may not suit the United States because true depreciation rates vary across countries for many reasons. Differences in the mix and scale of industries, relative prices of capital and labor, capital utilization, economic and financial conditions affecting investment, tax policies, and climate across countries may affect capital asset depreciation rates. Depreciation rates for structures reflect differences in building standards and land-use regulation. Regarding future updates of depreciation rates, the general recommendation was to proceed cautiously, given the numerous challenges in estimating depreciation (my emphasis).”

Moreover, it’s unclear whether the Canadian method is the same “superior” method used in the other four countries that are contrasted to the US. But if so, when did those countries start acquiring data on their capital stock that can be used to establish longitudinal trends? Ackerman refers to Shaikh’s exhaustive 150-page discussion and critique of the official US capital stock measures, but then simply asserts that the methods used, and the measures obtained in Canada and elsewhere are superior to the ones that Shaikh and others have always relied on (albeit sometimes with tweaks of their own).

Actually, the official US data on the life of assets does not seem to be too lengthy. It seems to conform to the IRS average of 8 years, excluding intangible assets. This is due to the BEA deriving its depreciation data directly from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Moreover, I compared the depreciation rates on capital stock for the US and Canada since 1985 from two main sources: the Penn World Table 10.1 series and the latest Extended Penn World Table Series 7.0 (the latter compiled by fellow Marxist economist Adalmir Marquetti) and used by the World Profitability Database—see below. This is what I found.

The Penn database finds that the US depreciation rate on capital stock was higher than in Canada from 1985 onwards—the opposite of the Monthly Review study. So, we have no strong reason to believe that the traditional US method for valuing capital stock is inferior to the new method that Ackerman touts (and the BEA economists tentatively put forward). He really hasn’t made the case.

Moreover, the annual change in the net stock of an asset equals the additional investment minus the additional depreciation. Depreciation is estimated as a residual. So, if we use gross capital stock (i.e., ignoring depreciation), we find that the US rate of profit falls significantly over the period 1985-2019.

This shows that Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is operating and the rate of profit will only rise when the counteracting factors, in particular, a rising rate of exploitation (i.e., increased profit relative to labor compensation) or the cheapening cost of capital stock additions, are stronger. Sometimes they are stronger, but eventually they give way to the underlying downward tendency.

No socialist or Marxist is opposed to reforms. The point is that if capitalism remains, regular crises in capitalism mean that capitalists will resist tooth and nail not only to oppose reforms but to reverse those already won by labor—as has happened in the neoliberal era since the 1980s.

Trying to measure the rate of profit has a host of issues involving data and method. Personally, along with some other Marxist economists, I think it is wrong to exclude variable and circulating constant capital from the measurement of the rate of profit, particularly as it can make a difference at least in the short term. Capital stock can be measured gross or net of depreciation, or on current (replacement) cost or historic cost.

And Shaikh7For those who want to suffer, read Shaikh’s section on gross and net capital stocks in his book, Capitalism, pages 801-3 (good luck!). and other scholars have shown that capital stock measures made available by national statistics are fraught with issues, partly because they are based on neoclassical concepts that tend to make the profit rate higher than it is.

But it’s not just measuring capital stock that has problems; so too does measuring profits. Are we including fictitious profits in the measurement of surplus value? Tax revenues? In the era of fictitious capital and massive debt, isn’t it necessary to distinguish between a non-financial rate of profit, a productive-capital rate of profit, a social-capital rate of profit, and a rate of profit on financial capital? To distinguish these, it’s necessary to make very different calculations of the surplus-value numerator. It ain’t easy, but we scrupulous scholars just soldier on—unlike the sectarians.

One thing worth adding about the Ackerman rate of profit compared to the BEA measure is that both agree there has been a fall in the US rate of profit since 2012 and virtually since 2006—a clear sign of stagnation in the 2010s. And both the Ackerman and BEA measures record a sharp fall in the ROP just before the Great Recession of 2008-9, suggesting the FROP played a role in causing that slump.

Ackerman also seeks to query the world rate of profit data provided by the excellent work of Basu et al. in their World Profitability Database (based on the Extended Penn Tables). Here he cannot show that depreciation rates are faulty.

Part of the reason is that, as he has already pointed out, in many other countries apart from the US, the rates are higher. And yet, as we see from Basu’s database and in many other national studies, profitability still falls in these countries (see below).

With his chart 6, Ackerman claims that this shows that it is the lower rate of depreciation of capital stock that is apparently the reason for a falling rate of profit, not falling profits (relative to investment), as the profit/investment ratio actually rose. But this seems to be perfectly in line with FROP. It means that for most of the period there was a rising organic composition of capital (i.e., fixed assets rose faster than labor costs) and profits from new investment were not enough to reverse that trend, so the rate of profit fell—exactly as the law of FROP predicts. It is interesting to note that the profit-investment ratio did fall from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, thus contributing to the very sharp fall in the rate of profit in that period. Something similar has happened since 2008.

In his graph for the European countries, Ackerman measures not profit against fixed assets, i.e., the rate of profit on capital stock (FROP), but profit against investment, i.e., the profitability of new investment. And he uses data from the EU AMECO database, which many of us “dogmatic” Marxists are cautious about using precisely because of AMECO’s dubious data on capital stock.8Lefteris Tsoulfidis and Dimitris Paitaridis, “Capital intensity, unproductive activities and the Great Recession in the US economy,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, vol. 43(3), 637. Instead, let’s look at the Basu et al. measures of the profitability of capital in those four countries over the same period treated in Ackerman’s graph.

We find that in all four countries the rate of profit on capital stock is lower in 2019 than in 1960. Profitability reaches a low in the early 1980s, then recovers up to 1997 or so, before slipping back down again after that (with Germany a bit later).

And remember that from the middle 1960s until the early 1980s, there was a huge fall in the rate of profit in the US and in all the major economies. And remember also that this coincided with two serious international slumps in 1974-75 and 1980-82. Subsequently, the major economies entered two decades of what has been called the neo-liberal period.

The likes of Reagan and Thatcher and their successors took back all the gains (reforms) that the labor movement had made in the previous decades. Trade unions were strangled; public services and welfare benefits were decimated; privatization of state assets was accelerated; and “globalization” took place, relocating manufacturing to the cheap labor platforms in the “Global South.”

All this enabled capital in the US and elsewhere to raise profitability to some extent from about 1982 to 1997. This is the period from which Ackerman’s data begins. After 1997 or so, the rate of profit (as in all measures above) flattened out or even fell, particularly during the “Long Depression” decade of the 2010s.

In my view, it is better to divide the era since 1950 into four different periods. First there is the “golden age” of relatively high growth, investment, and profitability (at least in the advanced capitalist economies), followed by a period of profitability crisis from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s as the law of FROP exerted its supposedly “statistical mirage.”

This led to intensified class struggle between capital and labor as capital tried to restore profitability at the expense of labor. In Europe, there were even revolutionary upheavals in Spain, Portugal, and Greece. In the neoliberal period, capital eventually won, and labor’s share of total value (GDP) plummeted, and the profitability of capital rose.

But this period passed at the end of the century as FROP began to assert itself once again and profitability fell, or at very least flattened out, at levels well below the 1950s and 1960s. The major economies then entered a period of low growth in GDP, investment, and trade—a depressionary decade before the pandemic hit.

Here is graph of profitability in the G20 countries that depicts these scenarios.

Utopian or scientific?

Finally, we must ask: what exactly is Ackerman’s objective in his article? Ackerman recognizes that FROP provides a powerful objective case for replacing capitalism. So, he looks for an alternative to FROP as the underlying cause of capitalist crises (and also the cause of the failure of planned economies apparently), which he reckons are “coordination failures,” and thus to crises of different kinds.

According to Ackerman, under capitalism, such failures take the form of “effective demand deficits”, which cause unemployment. Under centrally planned socialism they took the form of “Hilferding-esque disproportions” between the different branches of industry, which caused endemic shortages.” Both these causes of crises (underconsumption and disproportion) have been criticized as inadequate and/or wrong in many studies, which Ackerman fails to acknowledge.

So, I take it that the purpose of Ackerman’s article is mainly to argue that in today’s world we can achieve real and significant progress for humanity without revolution—without a complete and irreversible transformation of the capitalist mode of production into a socialist one. Ackerman seems to think that capitalism can and must be made into a more egalitarian system, and that, once the specter of extended periods of crisis has been exorcised, we can then look forward to an era in which the case for socialism can be made on a purely moral/ethical basis. We return to the view of Eduard Bernstein from the late 19th century.

If that is indeed his view, then its realism should certainly be ruthlessly questioned in a world that remains characterized by desperate poverty, rising inequality of wealth and income (particularly over the last 50 years), the existential threat of global warming and environmental degradation caused by fossil fuel and mining capital, and growing rivalries between competing “great powers” that are now threatening World War Three.

Ackerman accuses those who disagree with the gradualist approach to socialism of being sectarian, namely opposed to reforms and standing outside the immediate struggles by labor to improve their lot. But no socialist or Marxist is opposed to reforms. The point is that if capitalism remains, regular crises in capitalism mean that capitalists will resist tooth and nail not only to oppose reforms but to reverse those already won by labor—as has happened in the neoliberal era since the 1980s. If profitability is threatened, reforms must go.

So, can we really expect to end all this by simply reforming a social structure still controlled by several hundred capitalist combines? Can we expect the owners of those combines and the governments under their control to allow such reforms when they must involve inroads in profitability in order to be effective? Isn’t this an essentially utopian position, born not of scientific rigor, but of a boundless faith in capitalism’s reformability?