We are proud to have a strong analytical focus on social reproduction at Spectre. The current pandemic is tragically proving that which social reproduction theorists have long emphasized: that work needed to sustain life and life-making, such as nursing, teaching, cleaning—in other words, care work—is essential for any society to function. Indeed, it is care work that makes all other work possible.

A social reproduction focus, however, is not simply a philosophical position. It is simultaneously a political project. This is why during this time of crisis, we want our readers to hear the voices of workers fighting on the frontlines of care. The work of nurses, refuse workers, teachers, and farmworkers, among others, is sustaining us through this crisis. Our series, “Dispatches from the Frontlines of Care,” is designed to remind ourselves that it is the roles of stockbroker and corporate executive that are disposable, and we want a world where they remain so.

If you have a story for us, please write to the series editor, Tithi Bhattacharya, at tithi@spectrejournal.com.

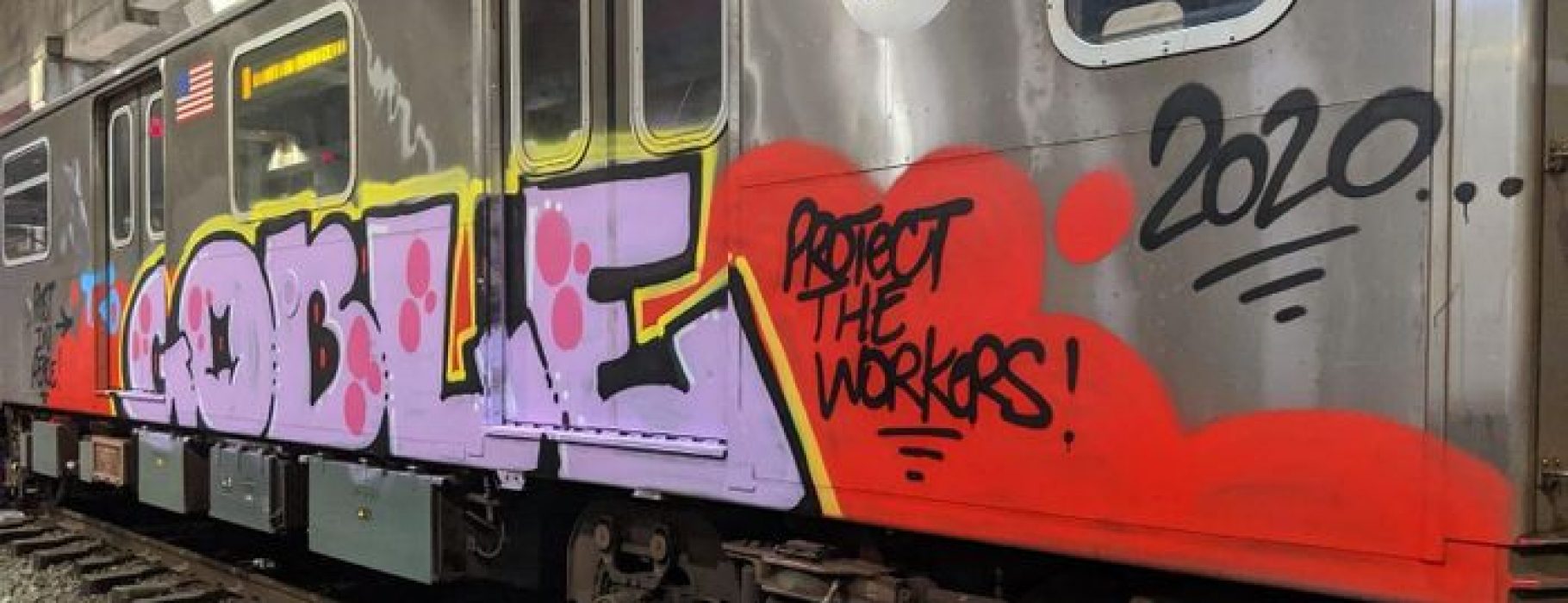

As of April 18, more than seventy New York City transit workers have died of complications from COVID-19. Many hundreds more have tested positive for the coronavirus, thousands have had to quarantine at home after being exposed, and others have called out sick until the safety conditions improve at work. These numbers are much larger than for any other “essential” public workers in New York City, but not surprising given recent data that shows the subway system has been a major disseminator of the disease here in the current epicenter of the pandemic.

The subways and buses are still crowded today despite a 93% drop in ridership. There have not been enough employees healthy and reporting to work to maintain the the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) reduced service. The resultant overcrowding has made social distancing on the trains and platforms impossible at peak times, while at other times the trains are providing “shelter” for unhoused people. When videos emerged of scores of packed subway trains, the MTA characterized the crowding as sporadic and promised that police would be forcing passengers to spread out on trains and platforms—as if safer locations actually existed.

Transport Workers Union (TWU) Local 100 represents more than 40,000 workers, most of whom work for the MTA and its largest subsidiary, New York City Transit (NYCT). I am a train operator and have worked in the subway for twenty-two years. In that time, close to twenty workers have died in accidents or attacks on the job, but the coronavirus has thrown us into an unparalleled situation of danger and death in the workplace.

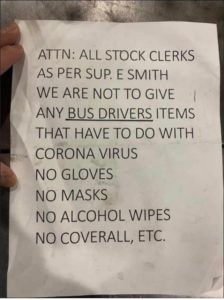

The first transit worker died of COVID-19 on March 26; more than four weeks later, after the media has begun to question the NYCT’s failure to distribute PPE and wipes, management now blames the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) for their own slow and insufficient response to the crisis. The MTA’s first responses were a warning that masks violated uniform policy and might scare passengers, and a sign posted in a bus depot supply room, that warned stock handlers that coronavirus protection materials were not to be issued to bus operators. At the moment, personal protective equipment (PPE) has begun to appear at worksites, but supplies are irregular.

The leadership of TWU Local 100 has responded to this crisis by following the lead of the MTA’s managerial leadership who are appointed by New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo. The union leadership has emphasized the heroism of the portion of the workforce that has continued to work through the pandemic. They have bragged about getting the MTA to agree to provide basic PPE and sanitizing materials—all more than a month too late and in insufficient quantities. The TWU 100 leadership has publicized the lip service that Cuomo and his newscaster brother paid to the sacrifice made by transit workers. They offered thoughts and prayers, and support for the families of the fallen workers. The union leadership’s biggest accomplishment so far is to get the MTA to offer the same, previously-negotiated, line-of-duty death benefit for all transit workers who die of coronavirus.

Rank-and-file militancy and solidarity remain the only solution to the crisis that COVID-19 poses for TWU Local 100 members.

What the union has not done is oppose Cuomo’s decision to keep the subways open through the entire crisis, and the mishandling of the crisis on the part of Cuomo’s hapless appointees who have cost the lives of many of the fallen workers. Most importantly, TWU 100’s leadership has not encouraged the members to use the contractually-provided procedures to stop unsafe work.

This is a continuation of the strategy followed over the last five to six years by both former local President John Samuelsen and current President Tony Utano. They have become political surrogates for Cuomo, going out of their way to attack his political rivals even when it alienates the union from potential allies and undermines the union’s power. Samuelsen, who is now the TWU’s International President, turned to the strategy of currying favor with Cuomo a few years into his nine-year stint leading Local 100, as he searched for a way to stabilize a formerly militant union still reeling from the aftermath of our 2005 city-wide strike.

That three-day transit strike, led by then-President Roger Toussaint, was followed by a contract rejection by the members, a re-vote, arbitration, a four-day jail term for Toussaint, $2.5 million in fines against the union, fines against individual members, and the temporary loss of automatic payroll deduction of union dues. The result was a combination of leadership collapse and membership disillusionment with militancy. The generation that has been hired in the last fifteen years has absorbed that cynicism and experienced a decline in Local 100’s power in relation to the employer, and a corresponding deterioration of their working conditions.

There are a few opposition groups within the union who have encouraged members to demand PPE, and to stay away from work until it has been provided. Some have distributed masks and sanitizer throughout the system, shaming the MTA and TWU into getting and distributing more supplies. They have used social media and press connections to publicize the MTA’s failure to follow their own policies and procedures designed to protect workers and passengers. One group has recently achieved electoral success in one of Local 100’s seven divisions. Unfortunately, most of these groups only exist on the internet. So far, they have not been able to overcome persistent infighting, and a tweet from a few years back from their leader offering to cross picket lines if Samuelsen called a strike.

Rank-and-file militancy and solidarity remain the only solution to the crisis that COVID-19 poses for TWU Local 100 members. We need to learn from, and emulate, the actions of health care workers, Amazon workers, Instacart workers, and our fellow transit workers in Detroit, Madison, and elsewhere, who have shown us that collectively refusing to work in unsafe conditions is the only way to protect ourselves and our families. The path taken so far has led only to death and death benefits.