The Evolution of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Syria’s Future

The Interplay between Islamism and Capitalist Geopolitics

November 25, 2025

Introduction

On September 24, 2025, an Islamist with solid roots in violent forms of salafism addressed the United Nations General Assembly for the first time in history and was welcomed warmly, if cautiously, by the West. What are the implications of this “Islamic” show of force for world capitalism following two decades where the West treated “salafi-jihadis” as the main global villains? How did Middle Eastern processes make this dramatic turn possible? Can global capitalism “tame” all major forms of Islamism, including its apparently fatal enemies? Answering these questions requires a deep understanding of both Syria and of salafism.

Fourteen years after the uprising against the brutal Assad regime, Syria’s new leaders promise a new regime with an orientation diametrically opposed to that of the toppled dictator. Western leaders are not unanimously enthusiastic, but a common sentiment appears to be that “there is no…alternative” and that the West should cooperate “as long as the al-Sharaa government continues to support integration and equality and peace throughout the country.”1As stated by James Jeffrey in late September 2025 – that is, only a short time after having witnessed the ethnic cleansings of the Alawites and the Druze. Ali Rogin, “Al-Sharaa promises a new video free of its ‘wretched past,’” PBS, September 24, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/al-sharaa-promises-a-new-syria-free-of-its-wretched-past. James Jeffrey was the US ambassador to Turkey and Iraq during the Bush and Obama administrations and a special representative for Syria engagement during the first Trump administration. However, the continuities between the new regime and Baath rule are remarkable, albeit paired with some possible ruptures. Syria remains an “Arab republic” in defiance of the country’s ethnic diversity. But now, the temporary constitution stipulates Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) as “the principal source of legislation,” signaling that Syria is on its way to also become an Islamic republic.2Constitutional Declaration of the Syrian National Republic, art III, cl. 1, available at https://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/2025.03.13%20-%20Constitutional%20declaration%20%28English%29.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Islamic jurisprudence was already listed as “a major source of legislation” in the constitution of 2012. Constitution of Syria in 2012, art. II, available at https://www.icnl.org/wp-content/uploads/Syria_Constitution2012.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com. This and many other aspects of the constitution and state policies and discourses clearly demonstrate that the Assad regime was not the bastion of secularism some held it to be. Joseph Daher, “How the Assad regime feigns ‘secularism’ while strengthening conservatism,” Syria Untold, January 14, 2022, https://syriauntold.com/2022/01/14/how-the-assad-regime-feigns-secularism-while-strengthening-conservatism/. Even though the future shape of Islamization is still unpredictable, the sectarian massacres first in Syria’s coastal region and then in Suwayda signal a victory for a particular kind of Islamism.

Bottlenecks in capital accumulation and interimperialist rivalry frequently lead empires and fractions of the local ruling classes to resort to ethnic, sectarian, or other divide-and-rule strategies. These dynamics also played a role in the religious and ethnic violence of 2025.3For the relations between neoliberalization and the recent sectarian strife, see Joseph Daher, “HTS’ strategy to Consolidate its power in Syria,” Syria Untold, July 28, 2025, https://syriauntold.com/2025/07/28/hts-strategy-to-consolidate-its-power-in-syria/. However, the number and intensity of actors who are willing to implement these divides in the most violent ways possible is distinct to the current situation. This cannot be explained without studying the twists and turns of politico-religious movements. In other words, the intensity of violent mass action depends not only on accumulation regimes and the local effects of world-systemic dynamics, but also on movement dynamics.4I discuss the theoretical framework for these claims in a talk titled “The Terminal Phase of American Hegemony or Revival of Fascism? Accounting for Violence in the Middle East through a Synthesis of World-Systems Theory and Structural Marxism.” The recording of this talk is available at online. “Global Political Dimensions of the Turn to the Right,” YouTube video, 34:18–49:15, posted by “globalcriticalstudies,” October 31, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OwoKarl9U0.

A proper contextualization of the more violent varieties of salafism is therefore necessary to gauge how al-Sharaa’s victory will impact the new Syria’s relationship with world and regional powers. Among the Sunni states, two are competing to take leadership of Syria’s transition. First, there is Turkey, which Trump—with some exaggeration—initially credited for the HTS (Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham) takeover of Damascus.5Jeff Mason, “Trump says Turkey holds the key to Syria’s future,” Reuters, December 16, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/trump-says-turkey-holds-key-syrias-future-2024-12-16/. The mediating power of Turkey is crucial to the global and regional balances of force but comes with many complications for the world’s hegemons. From a global standpoint, the main questions are: To what extent can Turkey’s governing Islamic party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), control the Syrian process? Can HTS, the ruling actor in Syria, follow a path parallel to the AKP? The AKP had absorbed Brotherhood-type Islamism into both Turkey’s institutional system and the world order of which it is a part. Can the cooperation between the HTS and AKP also absorb violent forms of salafism into the world order?

Saudi Arabia rivals Turkey in both its control of the new regime’s ideological direction and its hold over Syria’s resources and markets. Despite emerging as the apparent victor of the rivalry after Trump’s visit to the Middle East in mid-May, the kingdom is caught in challenging dilemmas. The Gulf monarchies’ increasing clout in Syria could give the Saudis some advantages over their Turkish rivals. However, both their relationship with the United States and their political economy set serious limitations to their (for now) intensifying influence. Their history with salafism adds further complexity to this already messy picture.

Even though this shouldn’t be taken as an absolute binary, the AKP and HTS come from rival traditions: the mass-based Islamic party (Muslim Brotherhood) route and the salafi route. One is allegedly more “moderate,” and the other apparently more sectarian. But both have uneasy relations with minorities and other world powers. They have occasionally morphed into each other, and reversals of that process are always possible (as witnessed especially in Syria’s last decade). The relationship of both routes to the Saudi (and more broadly, Gulf) tradition of top-down Islamization is also rife with contradictions.

Turkey and its allies are in search of a “tamed” Islamist rule in Syria, which would entail peace with Israel and the United States, smooth relations with world markets and Turkish and Western capital, and a restricted repression and marginalization of non-Sunnis. What are the indications that HTS could pull this off? How much of the original salafi agenda can HTS implement if securely in power? Would HTS, if entrenched, ever turn against Turkish, Israeli, and American interests? In short: Can global capitalism “tame” violent forms of salafism?

The Transformations of Islamism

For more than half a century after its foundation in the 1920s, the Egyptian-born Muslim Brotherhood served as the main inspiration for Islamic movements worldwide. With its extensive social movement and charity infrastructure, secret cadres, business networks, mass informal education, multiclass coalitions, and paramilitary training, the Brotherhood template was implemented throughout the world in building mass Islamic mobilization.6See, among others, Francois Burgat and William Dowell, The Islamic Movement in North Africa (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997); Dominik Mueller, Islam, Politics and Youth in Malaysia: The Pop-Islamist Reinvention of PAS (London: Routledge, 2014), https://doi.org/10.4324/94781315850535; Mohammed K. Shadid, “The Muslim brotherhood movement in the West bank and Gaza,” Third World Quarterly 10, no. 2 (1988): 658–82, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436598808420076; Lorenzo Vidino, 2010, The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230106871_8; Mohammed Zahid and Michael Medley, “Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Sudan,” Review of African Political Economy 33, no. 110 (2006): 693–708, https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240601119273.

However, one decade after another, all the routes tried by the Brotherhood-inspired organizations failed. Underground work, collusion with authoritarians, participation in electoral processes, uprisings, and other methods all resulted in suboptimal results.7Hazem Kandil, 2011, “Islamizing Egypt? Testing the limits of Gramscian counterhegemonic strategies,” Theory and Society 40: 37-62, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-010-9135-z; Nawaf Obaid, The Failure of the Muslim Brotherhood in the Arab world (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020), https://doi.org/10.5040/9798400649530; Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, 2015, The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement – Updated Edition, Princeton University Press; Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement – Updated Edition, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7h0t3j. Even though they contributed to a gradual Islamization of society, none of these secured durable governmental power.8Salwa Ismail, Political Life in Cairo’s New Quarters: Encountering the Everyday State (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). The 1980s and 1990s proved especially fatal, with the gradual erosion and ultimate repression of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, the crackdown on the Tunisian Ennahda, and the Algerian regime’s forcing of Islamists into a civil war.9Olivier Roy, The Failure of Political Islam (Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998).

The success of the Turkish AKP—ironically, outside the Arab world and in “secularized” fashion—was the only exception. The AKP revived hope for a while but left many Islamists across the world dissatisfied. It did not make implementation of shariah a priority. Islamic law is a shared value of both salafi and mass movement-based Islamists, even though it was never at the top of the agenda for the AKP and even its (relatively more Islamist) Turkish predecessors. AKP also fell short of another core goal of worldwide Islamism: distinguishing Islam as a third path distinct from “the West” (liberal capitalism) and “the East” (state socialism). With the second path gone, in the eyes of many the AKP became indistinguishable from the first.

Broadly speaking, the AKP started to lack a distinctive spirit as it became a part of the secular capitalist world. One indication of this loss was the evisceration of vibrant theological debate in Turkey. From the 1970s to the 1990s, debates between salafis, traditional Sunnis, modernist Islamists, and others constituted a core part of the growth—as well as internal difficulties—of the Islamist movement. In the 2000s, the main questions were the compatibility of (liberal or conservative) modernist theologies with the movement activists’, religious scholars’, and spiritual leaders’ relatively more traditionalist understanding of Sunni Islam and the shape of the salafi challenge’s incorporation into that broader ideological project. For most of their history, neither the Egyptian Brotherhood nor kindred movements such as the AKP aimed at theological standardization among Sunnis: compared to the salafis, these movements had the more modest goal of solidifying Sunni Islam in all its diversity—primarily against secularists and, secondarily, against non-Sunni creeds. As long as these movements retained a strong component of spiritual revivalism, diversity of theologies did not present a problem and even allowed for the religious activism of salafis and other nonstandard bearers of God’s message (at least in the outer circles of the movement).10Cihan Tuğal, Passive Revolution: Absorbing the Islamic Challenge to Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804771177. But once spiritual awakening and theological debates —now reduced to bare instruments in state-making and global business expansion—took a back seat in the 2010s, this laxness constituted additional “evidence” of weakness in the eyes of those skeptical of the Brotherhood. By contrast, global salafism intensified the vibrancy of internal theological debates. Salafis also improved their organizational effectiveness, even though incessant splinterism frequently undermined the impact of those improvements.

Even before salafism’s recent golden age, the disappointments with the Brotherhood line led to offshoots. Inspired by the hanged Brotherhood leader Sayyid Qutb among others, Islamists started to establish narrower organizations, specializing in violence rather than mass movement-building.11Gilles Kepel, The Prophet and the Pharoah: Muslim Extremism in Egypt (London: Al Saqi Books, 1985). These movements came to be called “jihadis,” or alternatively “salafi-jihadis” (referring to their puritan theology, which advocated the imitation of Islam’s first three generations). What was new here, though, was not the salafism as such but the decisively violent forms it was taking.

ISIS was puritan and (mostly) transnational, just like al-Qaeda. But it overcame al-Qaeda’s antistatism. Even though remaining extraterritorial in its ultimate ambitions, it made peace with temporary territorialization, as its name gave away: its immediate aim was building an Islamic state in Iraq and Syria (though the geographical focus and thereby the organization’s name would keep changing), with the aim of building a worldwide empire.

Varieties of salafi thought had existed for centuries and took many organizational forms, ranging from the scholarly and sectarian puritanism of Ibn Taymiyya through the top-down puritan Islamization of Wahhab (which would constitute Saudi Arabia’s official ideology) to the progressive salafism of modernist intellectuals such as Muhammad Iqbal. Other organizationally nondistinct forms of salafi “sensibility” have been also widespread. Indeed, a call to return to the roots of Islam and break with traditional religion as learned from parents and government-sanctioned imams has occasionally energized the grassroots activism of parties in the Brotherhood line.

What came to be called “salafi-jihadism” broke with these precedents not simply with its more insistent emphasis on violence (which used to have a circumscribed role in earlier salafi thought and practice), but also with its splinter-prone, focoist-like, cell-organizational structure. Many strands of contemporary salafism are also critical of Wahhab and others for their incomplete disavowal of the jurisprudence and theology of post-third generation Muslims. Saudi and Gulf money—their main sources of funding—further encouraged their puritanism, but had unintended consequences that eroded the kingdoms’ political and spiritual legitimacy

The political agendas of violent splinter groups were not clear in the beginning and appeared to be reactionary and lacked a positive agenda. They counted assassinations of authority figures (such as Egyptian president Anwar Sadat) and killings of American soldiers as their main successes. Even in the exceptional cases where armed Islamists secured a mass following, they were politically stuck. For example, while Taliban grew, thanks in large part to American and Gulf support and anger against the Soviets, it was not equipped to rule once it came into control of the country.

Other Islamic movements with heavy reliance on physical force should not be confused with violent varieties of salafism. For instance, Hamas and the Lebanese Hezbollah are both organizationally and theologically worlds apart. Even as they built up force as military organizations, they always worked hard at social provision, not surprising given Hamas’s roots in the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood. Hezbollah had even more opportunities to build business networks and become a part of an established state, but it remained isolated and relatively less ideologically influential among the Islamic movements in the region, mainly due to its Shia creed.12Hiba Bou Akar, For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018),https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503605619. In the end, due to the unique contexts of their formation, neither movement could come to act as transposable models.

This left al-Qaeda as the main counterpoint to the Brotherhood’s path. Al-Qaeda gave definitive form to those decades’ “counter-Brotherhood” ideological and political-organizational tendencies. Most importantly, it went beyond the haphazardness whereby some violent actors just happened to be salafis and some salafis circumstantially resorted to armed struggle. The organization definitively merged jihad, theological puritanism, takfir (excommunication with a violent twist), and the goal of a transnational caliphate.13Shiraz Maher, Salafi-jihadism: The History of an Idea (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). Salafism still has strong non-“salafi-jihadi” currents, which many scholars classify into two major camps (the quietists and the political salafis), although the lines between these are continuously contested and shifting.14Roel Meijer, Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199333431.001.0001.

Even though the global salafi field remains incredibly diverse, al-Qaeda and its offshoots emerged as a “model” that could be transposed and implemented anywhere in the world, and in that regard, they became the main counterpoint to the Brotherhood model of motivating and organizing Islamic mobilization. Armed salafis’ Protestant-like emphasis on the unmediated contact between God’s message and the lone individual received a further boost first from the extremely isolating and individualizing social trends of the post-1980s world culture, then from the internet and social media. Although proviolence, salafism’s demands from recruits are daunting; the twenty-first-century world proved an ideal context in which it could start to outpace the slow, patient, and less-adrenaline-boosting Brotherhood-route of Islamic mobilization. However, there were limits to what violent forms of salafism could accomplish in their most exclusive and purified form.

With its tight cell structure and fanatical puritanism, al-Qaeda gravely damaged its enemies, broadly defined. However, when it came to constructive rather than destructive tasks, its extraterritorial ambitions of a world Muslim empire kept it in a realm of fantasy. Unmoored from durable political and geographical institutions, al-Qaeda and similar organizations whipped the American empire into its own frenzy, pushing both sides into a global spree of indiscriminate killing and vengeance.

Salafism and the State Form

From the 1990s to the 9/11 attacks, violence and counterviolence occurred in pockets, rather than spreading to entire national territories or broader regions. The neoconservatives used September 11 to fundamentally change the game. Invading first Afghanistan and then Iraq, they dropped much of liberal imperialism’s appeals to civility and the rule of law and resorted to unabashed extractionism.

However, twenty-first-century American victories proved deceptive. The neoconservative assault succeeded at extraction and enriching Western oligarchs, but not in securing durable pro-Western rule in either Afghanistan or Iraq. Worse, its destabilization of the region intensified popular frustration with the reigning dictators, most of whom had cooperated with the invasions and the extraction of resources.

When the Arab Spring first erupted, the Western world saw an opportunity for further control, with Turkey acting as the proxy.15Cihan Tuğal, The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism, (London: Verso, 2016). In 2010–11, the liberal West misunderstood the nature of Turkey’s regime, which was thought to be headed in a liberal democratic direction. The AKP played along, seeking to export its model, primarily to countries with a strong Muslim Brotherhood tradition: Syria, Egypt, and Tunisia. Developing under the AKP’s foreign policy tsar Ahmet Davutoğlu’s leadership, the method of export evaded open aggression and sought to induce change through diplomacy, business ties, and political collaboration.

The failure of this export was a watershed for Turkey and the region. The AKP abandoned its “soft power” approach and started to cooperate and compete with the Saudis and Gulf monarchies in arming multiple Islamic groups. Qatar supported Jabhat al Nusra, but the Saudis supported other brands of salafism more, such as Jaysh al Islam. Even as the AKP shifted toward the world of armed salafis, armed salafis were shifting towards the center. For example, offshoots of al-Qaeda coalesced with Saddam Hussein’s ex-generals and officers to found ISI, which later became ISIS. With that coalition turning into a merger, a new era began in the Arab world.

ISIS was puritan and (mostly) transnational, just like al-Qaeda. But it overcame al-Qaeda’s antistatism. Even though remaining extraterritorial in its ultimate ambitions, it made peace with temporary territorialization, as its name gave away: its immediate aim was building an Islamic state in Iraq and Syria (though the geographical focus and thereby the organization’s name would keep changing), with the aim of building a worldwide empire. There were indeed signs that ISIS was faster than Taliban and former violent salafi authorities in renewing infrastructure and providing welfare to areas under its control. Armed salafis were learning to rule.

Intensifying Interimperialist Rivalry, the New AKP, and the Salman Regime

Along with Erdoğanism 1.0’s failures during the Arab Spring, intensifying interimperialist rivalry pushed Turkey further into cooperation with armed salafis. Ongoing failures of Western imperialism drew Russia into the Middle East. Russia’s growing presence further reinforced Iran’s ambitions. Iran was one of the main winners of Western failures in Iraq and the broader region. Even though watered down by federative power-sharing and the ongoing American occupation, the growing power of quasi-theocratic Shia forces in the country brought with it Iranian influence. The United States collaborated with Shi’a forces in power in Iraq but could not undermine Iranian influence as much as it desired. Other Iran-aligned actors gained further ground in the region (for example, Lebanon and Yemen) throughout the 2000s and 2010s. All in all, much like the Americans, these competing imperial and subimperial forces failed in institutionalizing any of their proxies or autonomous allies as lasting rulers.

Both Turkish businesses and military-intelligence actors prospered in this turmoil. Iraq, especially, became one of the hubs for both Turkish capital and a deepening alliance with Kurdish tribal leaders in the region against PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) allies. Ankara has been fighting the PKK for more than forty years. The guerilla organization’s primary social bases are in Turkey, but its influence extends over all of Kurdistan. The Barzanis—a specific tribe allied to the United States throughout the Cold War and a present-day partner of Israel—were the key figure in the growing bloc of pro-Ankara Kurds. Barzani-led forces, which had been Turkish allies for decades, now ruled the emergent Kurdish statelet in federative Iraq and welcomed Turkish businesses. However, the Arab Spring also led to the formation of Rojava, the Kurdish autonomous zone in Syria. For many in Turkey, this was an existential threat.

Al-Jolani is a master strategist, but doesn’t fetishize any one particular body of strategies. From 2013 to 2015, he emerged as one of the more pragmatic actors, in the sense that he was more open to coalition-building…But in the following years, al-Jolani still switched back and forth between approaches, occasionally taking a more pragmatic tack in some places and certain periods, then reverting back to puritanism, and then back to pragmatism again.

These waxing opportunities and perils changed the nature of the intelligence and foreign-service apparatus in Turkey. Traditionally molded with Mustafa Kemal’s nonexpansionist (if still anti-Kurdish) nationalism, “the deep state” was always suspicious of even the soft power neo-Ottomanism of the likes of Davutoğlu. There were certainly exceptions, such as the state’s similar soft-imperialist aims in Central Asia, which, though spearheaded by the new contingent of (neofascist) Grey Wolves or MHP (Nationalist Action Party) in the post-1980 official agencies, were also supported by most Kemalists. However, such expansionist adventures to the Middle East were always avoided.

Seeking allies against the American proxies within his own coalition (that is, the Gülenists), Erdoğan increasingly allied with right-wing Kemalists and the Grey Wolves throughout the course of the 2010s. The Gülenist coup in 2016 and the AKP-MHP coalition that resulted from the countercoup were only the visible culmination of a long reorientation process through which Erdoğanists not only shifted to an imperially aggressive interpretation of Islamism, but reintegrated putschist Kemalists back into the military. A grand coalition of Islamists, right-wing Kemalists (now imperially oriented), and Grey Wolves was born. Breaking with all precedent, the reformed “deep state” forces were ready to flex military muscles in the Middle East and North Africa.

These developments also eased the accumulation crisis in Turkey. The AKP followed a relatively more “neoliberal” and (apparently) hands-off approach in the 2000s. However, even in this decade, the government tempered neoliberalism with targeted welfare state policies and semi-official, AKP-connected charities. Yet, after the post-2008 slowdown of global cash flows, neither welfare nor charity was sufficient; promarket policies started to hurt the AKP’s own voter base more openly. In response, the AKP became more “state capitalist” in the 2010s. Intensified state involvement in the economy, including a government-led reindustrialization and re-unionization campaign, went hand-in-hand with militarization in that decade and helped boost employment, at least until the “orthodox” economic turn of June 2023. Even though these twists and turns did not create a sustainable path, they still bolstered popular wellbeing, popular emotional investment in expanded Turkish control over the region, and therefore (occasionally militant) popular support for the government.16Regarding the specific policies the regime deployed during this “state capitalist” turn, see Cihan Tuğal, “Politicized Megaprojects and Public Sector Interventions,” Critical Sociology 49, no. 3 (2022): 457–73, https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205221086284.

However, Turkey is still a strong contender in its bid to monopolize Islamism throughout the region. The Gulf monarchies, led by Saudi Arabia, perceive themselves to be the region’s legitimate rulers. Although certainly empowered by oil, their economies were never simply “rentier” economies, and their further integration into world capitalism over the last few decades created both new pressures and opportunities. The Salman regime took the lead in dealing with these constraints through a political economic overhaul at home and expansionism abroad.

For about two decades, the Saudis hoped that the infrastructure and construction boom would diversify the economy, break the kingdom’s dependence on oil, and erode crony capitalism.17Mohamed A. Ramady, The Saudi Arabian Economy: Policies, Achievements, and Challenges (New York: Springer, 2010), 335; Sarah Moser, Marian Swain, and Mohammed H. Alkhabba, “King Abdullah Economic City: Engineering Saudi Arabia’s post-oil future,” Cities 45 (2015): 71-80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.03.001. But the infrastructure/construction campaign did not lead to the leap in GDP growth that it did in Turkey, let alone living up to those dreams.18David Cowan, The coming economic implosion of Saudi Arabia: a behavioral perspective (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 37, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74709-5. Losing hope on this front, the Saudis (and following their lead, the other Gulf monarchies) now look to AI and other high-tech initiatives for a postcarbon future.19This assessment by no means implies that the construction-infrastructure drive was a failure on all fronts. It certainly supported the regime’s top-down Islamization aims, along with bolstering its cronies. See Rosie Bsheer, Jadaliyya, “The Property Regime: Mecca and the Politics of Redevelopment in Saudi Arabia,” September 8, 2015, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/32436/The-Property-Regime-Mecca-and-the-Politics-of-Redevelopment-in-Saudi-Arabia. They have been working with China on this front, which had led Biden to severely restrict any sale of American technology to the Gulf monarchies.

If internal diversification has not developed to the degree Salman desires, the same cannot be said of financialization and regional control. Gulf monarchies in general have been successful in channeling excess oil revenue into the development of banks and other financial services, and also in fueling this process further through reinterpretations of fiqh.20Ryan Calder, The Paradox of Islamic Finance: How Shariah Scholars Reconcile Religion and Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024), https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.8784660. The internationalization of this financial turn has picked up pace after the fall of the Soviet Union.21Adam Hanieh, Capitalism and Class in the Gulf Arab States (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230119604. Banks of Gulf origin control much of the money flows in the Middle East. Consequently, each war and territorial realignment presents openings for the Saudi-led monarchies to further expand their financial reach and ease the contradictions of their meandering transition to postcarbon domestic economies.

These multilayered pressures and opportunities, along with Wahhabi ideology, led the Saudis and their allies to play with fire in the broader region by selectively arming and facilitating salafis, whose ideology and weapons could ultimately threaten their very existence.

HTS and al-Jolani

HTS spearheads the “taming” and mainstreaming of violent forms of salafism, as well as the “nationalization” of the armed salafi mission—a project complicated by the presence of international fighters on HTS’s flanks. This new line resulted from a stormy process of transformation. HTS was established in 2017 by “al-Jolani”—nom de guerre of al-Sharaa, a Syrian from the Golan Heights, born in Riyadh in 1982 and raised in Damascus. Al-Jolani joined al-Qaeda in 2003 and fought in the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda. Imprisoned by Americans between 2006 and 2011, he moved to Syria in 2012 and founded Jabhat al-Nusra (al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate).

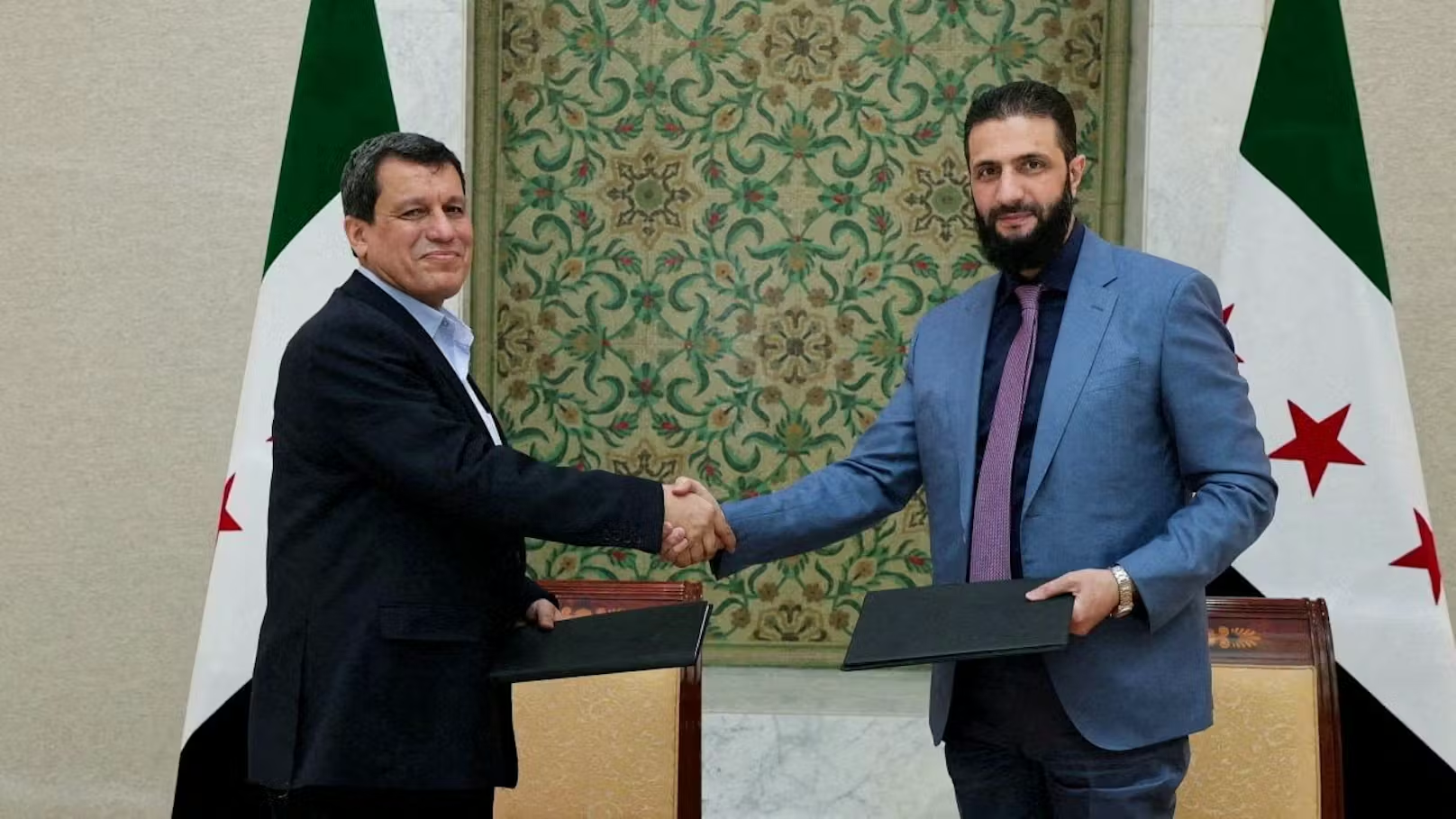

Photo Credit: Heute

Al-Jolani is a master strategist, but doesn’t fetishize any one particular body of strategies. From 2013 to 2015, he emerged as one of the more pragmatic actors, in the sense that he was more open to coalition-building (with both salafis and non-salafis) compared to other armed salafis and that he was able to merge the goals of global Islamic purification with the Syrian democratic revolution. But in the following years, he gradually shifted back to the puritanism of his earlier years. HTS, which was founded in 2017 as a merger of several Islamist groups under al-Nusra leadership, would differentiate itself from its salafi and other Islamist rivals with its harshness. But in the following years, al-Jolani still switched back and forth between approaches, occasionally taking a more pragmatic tack in some places and certain periods, then reverting back to puritanism, and then back to pragmatism again.

Before al-Jolani’s interventions, al-Qaeda had only a “resistance” presence in the region, reproducing earlier noninstitution-building patterns, while ISIS (initially ISI, when it was allied to al-Qaeda) controlled parts of both Syria and Iraq. However, Jabhat al-Nusra changed this equation. ISI and later ISIS had positioned themselves against both Assad and the Syrian revolution. By contrast, Jabhat al-Nusra tended to position itself as an ally of the revolution, even if it worked with ISIS in some periods and places.22Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and the evolution of an insurgency (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). The Free Syrian Army (FSA) and other forces fought ISIS and pushed it back to Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor (eastern and northeastern Syria). Jabhat al-Nusra, which was now deemphasizing its violent and salafi aspects in favor of Sunni-Syrian credentials, began to recruit Syrian revolutionaries increasingly dissatisfied with the FSA’s performance. FSA was also increasingly perceived as a proxy of Turkey after its Erdoğanist capture following conflicts between Turkish, Saudi, and Qatari ambitions.

Jabhat al-Nusra was founded explicitly as an anti-Turkish, anti-Iran, and anti-Western organization, even though it occasionally collaborated with Turkey from early on. Supported initially by Qatar, it was still publicly against Turkey in the mid-2010s, since Turkey is perceived by many armed salafis as a “secular” state. It openly fought against the Turkey-backed FSA.

Around 2015, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey started to coordinate and guide Islamic fighters in Syria. Yet, there were serious divides among the fighters regarding this guardianship. In 2015, Jabhat al-Nusra still opposed working with Turkey and condemned Ahrar al-Sham (another major armed Islamist organization) for doing so. Publishing op-eds in the Washington Post and Daily Telegraph, Ahrar sought Western backing as well. Alliances and divisions among armed Islamist groups, along with their realignments with regional powers, shifted almost monthly throughout the course of the 2010s. Jabhat al-Nusra’s rejection of Turkey was one of the few constants in this mindboggling maelstrom. However, after it morphed into HTS, the organization became more open to working with Turkey, even if their relations remained conflict-ridden.

Photo Credit: Qasioun News Agency via Wikimedia Commons

HTS ruled Idlib starting in 2017. Even though HTS usually built on Jabhat al-Nusra’s coalition-building approach in its operations across Syria, this was not the case during its initial years in Idlib, where it ruled with an iron fist. Turkey, going against both Western powers and Russia, approved HTS control over Idlib and HTS begrudgingly allowed the buildup of Turkish logistical and military power within the town. The two sides occasionally carried out common operations against Assad’s forces. This was a dark partnership, as both actors were highly suspicious of each other and used the dirtiest possible tactics to limit one another. For instance, Turkey is said to have assassinated the hardliners within the top HTS command, thereby killing two birds with one stone: making the organization less anti-Turkey and weaker.23Charles Lister, “Turkey’s Idlib incursion and the HTS question: understanding the long game in Syria,” War on the Rocks, October 31, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/10/turkeys-idlib-incursion-and-the-hts-question-understanding-the-long-game-in-syria/. The rocky partnership also occasionally degenerated into open clashes, as in early May 2020.

Even during their “cooperation” in Idlib throughout these years, the rapprochement between Erdoğan and HTS was never smooth in the rest of Syria. For instance, Turkey and its ally (increasingly its proxy), the Syrian National Army (SNA), occupied Afrin and its environs starting in 2018, which led to a cleansing of the Kurds. SNA merged the failing Free Syrian Army (FSA) with a diverse group of actors that included the Turkmens, Islamic groups, and whatever remained of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. Until 2022, SNA and Turkey kept the region an HTS-free zone. However, SNA’s cronyism and infighting provided openings for HTS’s ongoing incursions. HTS mounted a months-long campaign to take Afrin from Turkish-backed forces before ultimately succeeding in late 2022.

This event had broader repercussions. The degeneration of the SNA served as further proof in the eyes of armed salafis throughout the Middle East that the Brotherhood-line, even in its militarized versions, was a recipe for corruption and weakness. Turkey’s AKP further reinforced this perception, as this “Islamic” party’s clear priority was the Turkish state’s anti-Kurdish agenda (that is, the stifling of Rojava), rather than instituting sustainable Islamic or democratic rule in Afrin and beyond. As Erdoğan made several attempts at normalization with Assad throughout the two years that preceded Assad’s downfall, it was precisely al-Jolani who led the pack in voicing the opposition of both the salafis and the Syrian revolution against the emergent Turkey-Syria pact.24“Al-Julani embarasses the Syrian opposition in a statement rejecting Turkish normalization with Assad,” Syria TV, January 2, 2023. https://www.syria.tv/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%AD%D8%B1%D8%AC-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%B6%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B6-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B7%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%8A-%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%AF.

Western media are divided regarding HTS’s Idlib record. CNN and the New York Times draw a benign picture today: HTS first imposed Islamic law but then tempered it. In contrast to these post-Assad portrayals, even mainstream venues such as the Economist covered al-Jolani as yet “another dictator” as recently as March 2024. HTS imprisoned many activists and mistreated locals, giving rise to protests last year.

…in mid-March the New York Times framed the recent violence in line with the Syrian president’s explanation of the events as resulting from the lack of such monopolization.…Rather than resulting from the incomplete monopolization of legitimate violence, the violence in March resulted from the ongoing process of monopolization itself.

On the way from ruling the relatively small town of Idlib to taking over Damascus, al-Jolani had to fight, defeat, recruit, and compromise with dozens of Islamist factions before global and regional powers made their peace with him and started to support him. Especially starting with 2020, it appears that Idlib served as a hub for several foreign players that trained and sought to influence armed Islamists. Along with the publicly acknowledged Turkish leadership in these activities, speculations abound regarding sources of foreign funding and logistical support, and how some of that might have enabled the march on Damascus. This essay will not attempt to adjudicate between these speculations but will rather focus on how HTS rule might shape Syria and the broader region, given the historical background analyzed above and the events that followed the march on Damascus.

An Islamist Syria?

There are persistent ambiguities surrounding both the future and the character of HTS’s reign.

The organization does not yet control all of Syria. Furthermore, Israel has destroyed much of the country’s defense capacity. The Druze and the Kurds are still armed. Israel, the United States, Russia, and Turkey all have armed forces on Syrian territory. Just as importantly, HTS does not have full control over the armed Islamic actors allied with it, even if the latter have deceptively “disbanded” and joined the Syrian army.

HTS’s regional priorities are not clear. Its first foreign visit was to Saudi Arabia and then to the Gulf sultanates, signaling that its “model” and ultimate protector might be the Gulf rather than Turkey. But the visit could also be interpreted as a fake-out, trying to hide Turkey’s ultimate leadership. (Erdoğan was planning his visit in early January but postponed it to stave off reaction). Or perhaps, taking stock of Turkey’s camaraderie, HTS is diversifying its spectrum of allies—much like the AKP itself relies on a series of partners in the region and the world. In early 2025, the government and opposition in Turkey were fighting daily over the ultimate meaning of these visits.

From December 2024 through early March 2025, there were conflicting reports regarding HTS’s treatment of Alawites. While granting Alawites were worried, most mainstream sources (Turkish and Western) insisted that there were no major incidents. By contrast, opposition sources reported ethnic-sectarian violence even before March. HTS and the mainstream said that all reported violence emanated from stray forces, not condoned by HTS’s top command.

One of the main fault lines within the emergent regime is the rift between Syrian and foreign fighters, especially Chechens and other Central Asians. Although most of the violent cleansing of the following months seem to be committed by Syrian fighters affiliated with the government, these foreign fighters were deemed to be behind the vicious attacks against the Alawites in the first weeks of the new regime and symbolic actions like the burning of the Christmas tree in a Christian-majority town. While HTS cannot afford to alienate foreign fighters, it is virtually impossible to incorporate them into a tamed salafi state.

Moreover, in this complex process of state-making, it is not clear who is taming whom. The initially Turkish-aligned and Brotherhood-dominated Syrian National Council, which was recognized as Syria’s legitimate government in 2012 by more than one hundred countries, declared in mid-February that it would dissolve itself. This could be seen as another confirmation of the defeat and absorption of the “Islamic/liberal-democrat” option—and, more broadly, of the Brotherhood-leaning Islamist tradition—into the HTS-controlled state.

Having secured Western support and regional Sunni alignment, HTS convened a national conference during the last days of February without participation from the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, Alawites, and the Druze. The conference did not include any representatives of political parties, trade unions, or professional associations. There was a representative of Christians—likely a move designed to send HTS’s good graces to the West—but not as a representative of any organized group. This February conference followed up on a first, more restricted gathering of the same kind. Both conferences confirmed the Sunni-Arab nature of the emergent regime. The cabinet formed at the end of March repeated the same pattern: the new executive included token individuals from minority groups, but unlike the HTS figures in the cabinet, these individuals did not represent any organization or movement. Meanwhile, Israel expanded its military operations in February, destroying yet more military equipment, beyond the southern regions it had initially hit upon the fall of Assad.

In early March, Sunni-Islamization took a more dramatic turn, both at the street level and institutionally.

“The monopoly of legitimate violence”

More than one thousand Alawites, most of them civilians, were killed in Syria’s coastal region within just seventy-two hours in early March. Many killings were execution style.25A United Nations report in August failed to confirm that the massacres were planned and implemented by the regime itself but pointed out that they were coordinated and planned; the groups that carried out the massacres were organized by HTS in its earlier history; and the regime’s forces participated in them. It also emphasized the killings are ongoing, even if not as intensely as in March. Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, Violations against civilians in the coastal and western-central regions of the Syrian Arab Republic (January–March 2025) (Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Council, 2025), available at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session59/a-hrc-59-crp4-en.pdf. These appeared to be revenge killings, given that Assad was of Alawite origin. While often characterized falsely as an Alawite regime, Assad’s rule actually depended on power brokering between several prominent families of various sects. Even though Alawites predominated in this arrangement, especially in the security sector and sectors of the army connected to Maher al Assad, it was an oligarchic more than a sectarian dictatorship. Much of Assad’s Alawite support was out of fear of a worse alternative.26Bassam Haddad, Business Networks in Syria: The Political Economy of Authoritarian Resilience (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804778411. Moreover, warring regional powers (Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey, among others) boosted Shia and Sunni sectarian movements to widen their scope of influence and the oligarchic families welcomed the interventions that favored them in the balance of power. These divisions gained additional importance after the turn towards market economics and away from corporatist policies beginning in the late twentieth century and gaining pace in the 2000s. Increasingly devoid of economics-based legitimacy among peasants and workers, the regime intensified its use of ethnic and sectarian divisions as tools of control.27Joseph Daher, “Popular Oral Culture and Sectarianism, a Materialist Analysis,” Syrian Untold, October, 31, 2018, https://syriauntold.com/2018/10/31/popular-oral-culture-and-sectarianism-a-materialist-analysis/#_ednref13. Alawite popular classes suffered along with Sunni popular classes under this arrangement, and the winners were a handful of oligarchic families and their international benefactors. While misplaced revanchism may have contributed to the March massacre, broader forces of state-making were at play.

Max Weber’s name and arguments, always popular in the Turkish intellectual scene, experienced a golden age in the news cycle too in late 2024 and early 2025. Academics; military history experts; journalists; and commentators on television, YouTube, and other channels resorted to Weber’s definition of the state (a human community successfully claiming the monopoly of legitimate violence within a territory) in light of the ongoing talks regarding the PKK’s dissolution and the disarmament of dozens of Kurdish, Islamist, and other military and paramilitary groups in Syria.28Nuri Salık, “Suriye’de Yeni Devletin İnşası,” Türkiye Araştirmalari Vafki, February 19, 2025, https://www.turkiyearastirmalari.org/2025/02/19/yayinlar/analiz/suriyede-yeni-devletin-insasi/; Gültekin Yıldız, “Yeni Bir Devletin İzinde: Suriye’de Yeni Ordu Nasıl Mümkün Olacak?” Perspektif, December 28, 2024, https://www.perspektif.online/yeni-bir-devletin-izinde-suriyede-yeni-ordu-nasil-mumkun-olacak/; Max Weber, [1919], “Politics as a Vocation,” in From Max Weber (Oxford: Oxford University Press), ed. H.H Geerth and C. Wright Mills, 77–128. Without explicitly naming the sociologist, the Western press also drew on Max Weber’s standard definition of the state. For example, in mid-March the New York Times framed the recent violence in line with the Syrian president’s explanation of the events as resulting from the lack of such monopolization.29Ben Hubbard, “Syria’s Struggle to Unify Military Was Evident in Outburst of Violence,” New York Times, March 17, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/17/world/middleeast/syria-military-assad.html.

This framing neglects the critical social sciences’ decades-old criticism of Weber’s definition: the identity and the purpose of those monopolizing “legitimate” violence in the name of “the state” matter.30Jennifer Carlson, “Revisiting the Weberian Presumption: Gun Militarism, Gun Populism, and the Racial Politics of Legitimate Violence in Policing,” American Journal of Sociology 125, no. 3 (2019, ): 633–82, https://doi.org/10.1086/707609. Moreover, states frequently work with nonstate violent actors to realize their aims throughout and after this process of monopolization.31Cihan Tuğal, “The Decline of the Monopoly of Legitimate Violence and the Return of Non-State Warriors ” in The Transformation of Citizenship, Volume 3: Struggle, Resistance and Violence, ed. Juergen Mackert and Bryan S. Turner (Routledge: London and New York: 2017), 77–91.

After distinguishing himself as the voice of moderation and pragmatism within armed salafi circles, al-Jolani declared—at the peak of his “moderate” phase in 2015 and before yet another shift back to a harsher form of violent salafism—that his forces would not harm Alawites as long as they abandoned their religion.32AFP, “Chief of al-Qaeda’s Syria affiliate pledges no attacks on the West,” Middle East Eye, May 28, 2015, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/chief-al-qaedas-syria-affiliate-pledges-no-attacks-west. For armed salafis, violence against Alawites (and more generally, non-Sunni Muslims) has been a top agenda item for a long time. Even though al-Jolani’s objectives might have shifted, this global movement has been cultivating cadres and militants dedicated to such harm. A good number of these militants are now either allied with or a part of the new Syrian security forces. They are likely to find more opportunities to implement their objectives, which are not entirely out of line with the temporary constitution’s goal of building a Sunni state.

Rather than resulting from the incomplete monopolization of legitimate violence, the violence in March resulted from the ongoing process of monopolization itself.

Almost simultaneously with this violence, al-Jolani (who shifted back to his birthname al-Sharaa after he took Damascus) declared a new temporary constitution, with Islam announced as the principal source of legislation in the second article. The new constitution grants exceptional powers to the president and promises rights to women and minorities. In fact, the pro-HTS pan-Arab press, including Qatar’s semi-official newspaper, saw the rights granted to women and minorities as further proof that HTS had finalized its break with “jihadi ideology.”33Muhammad Abu Raman, “Al-i‘lan al-dusturi wa al-qati‘a ma‘a al-idiolojiya al-jihadiyya,” Al-Araby al-Jadid, March 16, 2025, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/opinion/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B7%D9%8A%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%8A%D8%AF%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%84%D9%88%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9. However, given that HTS simultaneously oversaw a historic massacre while promising such rights, critics pointed out that the application might not be in line with the promise.

Some Druze forces denied recognizing the constitution, declaring al-Sharaa illegitimate by extension. Others remained silent. While there were conflicts between HTS-controlled security forces and the Druze, the violence was minimal until mid-year. Israel presents itself as the protector of the Druze in the region, and Netanyahu attempted to intervene on behalf of them in cases of heightened tension. Despite the alleged emergence of some more explicitly pro-Israeli armed factions, public embrace of Israel’s role as a guardian was quite restricted until the deaths of forty people over two days of clashes in May.34Kareem Chehayeb and Omar Sanadiki, “Syria’s Druze seek a place in a changing nation, navigating pressures from the government and Israel,” AP News, March 10, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/syria-druze-damascus-alsharaa-sweida-war-ace48a6e138dc1197cca77c3d25d829b.

It is no coincidence that the HTS-led march on Aleppo started very soon after the American elections…Even if not directly guided or egged on by the Americans, the armed salafis must have also chosen this moment deliberately, reading it as a power vacuum and, more broadly, the beginnings of a world where local actors’ military campaigns determine more than they used to under pre-Trump conditions.

Amid these tensions, news of kidnappings, attacks, robberies, and other tribal rivalry between the Druze and Bedouins of Suwayda started to circulate in July. Security forces allied with Arab tribes soon joined the fray. Close to a thousand Druze were massacred in only a few days. The government and its regional allies (such as Turkey) blamed the clashes on Israel, who in fact participated in the clashes.

The Western press has been framing the problem in terms of the lack of centralization. A New York Times article argues that “a unified military is crucial to securing control over the entire country and establishing stability,” implying that the recalcitrant Druze prevent this intuitively universal desirable end.35Christina Goldbaum and Reham Mourshed, “These Militias Refuse to Join Syria’s New Army,” New York Times, April 1, 2025, updated April 14, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/01/world/middleeast/syria-israel-border.html. But the coordinated and ideological nature of the attacks in July, including widespread forced shaving of Druze mustaches, again attest to a process of monopolization rather than lack thereof.

The Kurdish Question

The mid-March decision by Syrian Kurds to become a part of the national army appeared to be a historic turning point for both the entire region and salafism. Al-Sharaa’s strategic and diplomatic wisdom was again confirmed by combining three formidable accomplishments—garnering Western and pan-Arab consent (or at least quiescence) for a fiqh-based constitution, reaching an apparent deal with the Kurds, and overseeing a sectarian massacre—within the same week. However, later developments cast a shadow on the prospects for the implementation of al-Sharaa’s deal with the Kurds.

The Kurdish population remains divided across four countries.36David A. McDowall, 2007, A modern history of the Kurds (London: I.B. Tauris, 2007). The emergence of the autonomous administration in Rojava revived the dream of unification for some and (along the lines of the Kurdish movement’s current dominant ideology) provided an institutional model that could be transposed across the region for others. The most prominent Kurdish leaders and intellectuals have upheld the value of “autonomy,” both for Kurds and for each population throughout the Middle East. From the beginning, HTS has been inflexible regarding a federative resolution for the Kurds and called for a unitary state, under tight Damascus control.

The Erdoğan regime intervened in the situation even before al-Jolani’s march on Damascus. Erdoğan’s main coalition partner, MHP’s leader Devlet Bahçeli, invited the imprisoned guerilla leader Öcalan to speak in the Turkish parliament and declare the end of the PKK.37The PKK leader Öcalan had started out as a Marxist-Leninist in the 1970s. Following the early 1990s, the PKK prioritized national liberation and drew the Kurdish bourgeoisie into supporting armed insurrection. Imprisoned in 1999, Öcalan discovered Bookchin in his high-security cell and repudiated Marxism-Leninism. Today, the movements and organizations associated with him unevenly combine Bookchinite communalism, Marxism-Leninism, and emancipatory nationalism. Öcalan and pro-Öcalan Kurdish military leaders, still on the official “terrorist” list, were de facto recognized as legitimate political actors. One of the main aims of this initiative is toning down Kurdish ambitions by pardoning Öcalan and, possibly, other Kurdish fighters. In exchange, Erdoğanists apparently hope for Kurdish support for Erdoğan’s lifetime presidency, the disarmament of Kurds (in both countries), and commitment to the non-federative nature of both Syria and Turkey. Whether autonomy, linguistic/cultural rights, and nonethnic redefinitions of nationhood are on the table is still subject to endless speculation in Turkey and in Western and Arab media. Neither Erdoğanists, nor HTS, nor the Kurdish movement have revealed the exact stakes of the ongoing negotiations.

The American stance in this process has been far from clear. The United States allowed Turkey to take over Manbij in December 2024. However, they also protected Kobani from Turkish military assault in post-Assad Syria. Even Trumpists, keen on withdrawing from Syria, were vociferous regarding America’s duty to protect the Kurds when Ankara prepared its assault. Despite this seeming contradiction, the progovernment Turkish press remained resolutely pro-Trump. They believed that Trump would override all concerns and stop supporting the Kurds, and attributed all wavering to “Zionist” (or other malicious) influence. They anxiously anticipated January 20, thinking Trump would soon step in. However, Trump initially remained silent on the issue, focusing mostly on Ukraine, internal affairs, and his overblown ambitions regarding Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal. The late March meeting between Minister of Foreign Affairs Hakan Fidan and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio also failed to generate any meaningful signals regarding the American stance.

The situation in Syrian Kurdistan is at least as complicated as in Turkey. Following the deal between HTS and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which includes the latter’s integration into the national army, some commentators announced the decisive end of armed conflict. But others warned that the real issue would be implementing the ambiguous deal. Even though the document stipulates the integration of all armed forces and infrastructure across the nation, Kurds still expect to retain the autonomy they have already gained, even if the word autonomy is no longer used as vociferously. Some of the issues allegedly on the table in the ongoing negotiations—local control over oil revenues and infrastructure, promises of high-ranking positions in the military—appear to open the door to either real Kurdish power within the system without an explicit federation or else a Lebanese-type power-sharing arrangement.

Photo Credit: Heute

Meanwhile, Fidan and intelligence chief Kalın travelled to Syria right after the agreement was signed so as to make de facto autonomy impossible. The mood in Turkey also quickly changed: while initially celebrating the pending disarmament of Kurds, the more nationalist elements in both the broader public and the regime’s media started to express concerns that the Kurdish fighters’ joining of the Syrian army might hint at the formation of Kurdistan. With less intense alarmism, Hakan Fidan himself suggested that the deal appears to involve malicious aspects that could produce undesirable results for Ankara, especially regarding YPG (The People’s Defense Units—that is, the Kurdish armed units that lead the SDF).38Haber Merkezi, “Fidan’dan, Colani-Mazlum Abdi anlaşmasına kritik açıklama: Suriye Külterinin haklarının verilmesi hem Cumhurbaşkanımız hem de Türkiye için fevkalade önemli,” T24, March 14, 2025, https://t24.com.tr/haber/fidan-dan-sam-sgd-anlasmasi-hakkinda-kritik-aciklama-suriye-kurtlerinin-haklarinin-verilmesi-hem-cumhurbaskanimiz-hem-de-turkiye-icin-fevkalade-onemli,1225921. Along the same lines, Turkey’s 2009–12 ambassador to Damascus hinted in a Saudi magazine at the slow formation of greater Kurdish unity across the region and Kurdish autonomy within Syria, without older watchwords like federation being uttered.39Ömer Önhon, “Reading between the lines of the Sharaa-Abdi deal,” Al Majalla, March 14, 2025, https://en.majalla.com/node/324731/politics/reading-between-lines-sharaa-abdi-deal. Also, only three days after al-Sharaa and the Kurdish leader Mazlum Abdi signed the deal, the SDF-led Rojava administration rejected the temporary constitution, pointing out that it reproduces a Baath mentality, defies the Syrian Revolution, and neglects both the democratic aspirations of Syrians and their diversity. Such sharp criticism was not expected by Erdoğanists and their Syrian allies, which again shows that their initial hopes regarding Kurdish subservience and a smooth Islamist victory were inflated.

The first weeks of summer brought with them another wave of euphoria among Turkish governing circles and their international allies. Öcalan’s ultimate call to lay down arms and the top PKK leaders’ ceremonial burning of their weapons were greeted with stunned applause. However, even this step proved indecisive. The persistence of armed and autonomous Kurds in Rojava sympathetic to the PKK line showed the limits of the process. Hakan Fidan used the Druze massacre as a warning against the Syrian Kurds, pointing out to them that they should not take their lives for granted. But the overall atmosphere created by the massacre backfired. After observing the fate that befell the Druze, Syrian Kurds became less willing to give up recourse to armed self-defense. As I finalized this essay in mid-November, the demilitarization of Syrian Kurdistan was moving at a snail’s pace.

Saudi Ascent and the Still-Fragile Realignment of Global Forces

It is no coincidence that the HTS-led march on Aleppo started very soon after the American elections. Even a cursory look at the regional press reveals that Netanyahu, Erdoğan, and the Sunni monarchies interpreted Trump’s election as a blank check for their ambitions. Even if not directly guided or egged on by the Americans, the armed salafis must have also chosen this moment deliberately, reading it as a power vacuum and, more broadly, the beginnings of a world where local actors’ military campaigns determine more than they used to under pre-Trump conditions.

Nevertheless, the US foreign policy and military machines are still not united in either their approval of Islamist control over Syria or their will to minimize apparent US involvement in the country. The new administration has followed mixed strategies, with no clear mission statement on the horizon. Most commentators in the Turkish and Arab media feel certain that the United States is behind the HTS-SDF deal, but it is unlikely that the Americans are guiding this process with a clear and consistent agenda. In February, the Pentagon gave signals of troop withdrawal. However, intelligence chief Tulsi Gabbard spoke harshly against HTS and Islamists, stating that they would never democratize, that they are not reliable partners, and that American soldiers should not leave the area. After the massacre in March, Fox News and other conservative venues celebrated Gabbard’s foresight, signaling likely pushback from within Trump’s own administration and his broader coalition against his desires regarding the Middle East.

Trump’s own dream, as attested to by his trust in Erdoğan, appears to be withdrawing American troops and resources as much as possible from Syria and the broader region, while delegating Turkey and Erdoğan (and paradoxically, some anti-Erdoğan Kurdish leaders) to enforce US interests.40Fehim Taştekin, a journalist with village-by-village knowledge of especially Northern Syria, as well as ample contacts in foreign policy circles, outlined the apparent parameters of the negotiations between Americans, the Kurds, and Erdoğan. “Dış güçler Erdoğan’ı kurtarıyor mu? İsrail’le kullanışlı gerilim. Suriye’de çatışmasız çakışma,” YouTube video, 22:33, posted by “Fehim Taştekin,” March 25, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbhaKd79Kno. Also see Fehim Taştekin, “Trump, Erdoğan ve Putin’in haritaları!” Gazete Duvar, January 9, 2025, https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/trump-erdogan-ve-putinin-haritalari-makale-1748317. This is a dangerous gamble, and Trump might change his calculus as quickly as he turned against Erdoğan back in 2018. Despite all the Erdoğanists’ emotional and strategic investment in Trumpism, the American administration shies away from consistent and united messages. For instance, US special envoy Steve Witkoff’s over-the-top evaluation of Erdoğan-Trump relations was followed shortly by the Rubio team’s lukewarm appraisal of Turkey after Rubio’s meeting with his counterpart Fidan.41“Trump-Erdogan talks ‘great-transformational’ but ‘under-reported’: US Envoi,” Middle East Monitor, March 22, 2025, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20250322-trump-erdogan-talks-great-transformational-but-under-reported-us-envoy/; Tammy Bruce, “Secretary Rubio’s Meeting with Turkish Foreign Minister Fidan,” U.S Department of State, March 25, 2025, https://www.state.gov/secretary-rubios-meeting-with-turkish-foreign-minister-fidan-2/.

via TruthSocial

Trump and his team’s calculus is much more complex when it comes to Syria-Israel relations. Although the most hawkish elements within Trump’s orbit distrust HTS, the organization’s apparent change of stance on Israel soothes come conservative worries. HTS rule seems to be better for Israel than other realistic alternatives. Ever since he came to power, al-Sharaa has been emphasizing that he doesn’t want war with Israel. We don’t know if he would ever go as far as completely abdicating the Golan Heights, but for now he has voiced minimal reaction to the further expansion of Israel’s occupation of Syrian territory. Israel’s intensifying involvement in the Druze issue has certainly shown the limits of the brotherly nature of the conflict between Netanyahu and al-Sharaa, but we need to keep in mind that al-Sharaa remained a Turkish ally even after many bloody spats with Erdoğan’s forces (during his days as “al-Jolani”). Even if Israel still can’t completely trust HTS, its leader’s stance has ensured that the occupiers will, in the words of Israeli sources, “respect and suspect” him, rather than seek his immediate removal.42Yoni Ben Menachem, “Abu Muhammad al-Jolani’s Attitude Toward Israel,” January 2, 2025, Jerusalem Center for Security and Foreign Affairs, https://jcpa.org/abu-muhammad-al-jolanis-attitude-toward-israel/.

At least for now, Iran is the main loser among regional powers. Iran was already having a hard time managing the post-October 7 conflict. With the fall of Assad, the regime lost an ally. Moreover, Assad’s fall meant both the victory of some of the most fanatically anti-Shia ideologues in the entire world (given the global influx of armed salafis to Syria) and the failure of its delicate strategy to contain the Gaza conflict while still supporting Hamas.43Eskander Sadeghi-Bouroujerdi, “On the Brink,” Sidecar (blog), October 7, 2024, https://doi.org/10.64590/sw7. Iran now faces even more frequent calls for regime change from Washington and occasional threats of war.

Al-Jolani’s rise to power was also a blow to Iran’s regional allies. Hezbollah, after losing an unprecedented number of leaders and soldiers during the preceding months, signed an unfavorable ceasefire with Israel on November 27, just as HTS was initiating its takeover of Aleppo.44Suleiman Mourad, “Hezbollah Contained,” Sidecar (blog), December 4, 2024, https://doi.org/10.64590/mcd. In January, Joseph Aoun, whom the Sunni pan-Arab media hailed as a strongly anti-Hezbollah leader, became president of Lebanon. Although he has sought some common ground with Hezbollah (again unfavorable to the organization) rather than declaring all-out war against it, Aoun simultaneously set about mending Lebanon’s ties with Saudi Arabia.

While the emergent class structure is far from clear given the chaotic state of the economy, two processes must be noted: First, the transfer of wealth from Assad cronies to businesses connected to the new regime; second, Saudi-led Gulf capital’s oversight of the privatization of government lands and buildings to carry out a Dubai-like transformation.

All of this is a mixed victory for the Saudi kingdom. Not only has Assad been toppled, but the regular Brotherhood-type forces (one of the greatest fears of Arab monarchies) have failed to assume leadership of the transition. A salafi is at the helm of the new state, which could be counted as an ideological victory for the kingdom in the long-term balance sheet of theological struggles in the region. However, “Al-Jolani’s” salafism used to be of the kind that has annoyed the monarchies during the last decades due to its more consistent puritanism, thorough politicization, and antistate implications. Even if al-Sharaa seems to have dropped some elements of his former ideology, his tendency to shift back and forth is well known and could cause trouble for the Saudis in the not-too-distant future. And although the new regime keeps on repressing some of the foreign fighters, the incorporation of thousands of other foreign fighters into the Syrian National Army and its top positions is an ongoing process with unpredictable consequences for regional balances.

None of these worries prevented Saudis and other royal powers from funding armed salafis in the past, but always with the awareness that these weapons could one day be turned against themselves. Consequently, the Saudi press is mixed. Al-Sharq al-Awsat and the television channel al-Arabiya (the kingdom’s pan-Arab alternative to al-Jazeera) have been celebrating “the end of ideology and of Islamism” in the region (meaning, the victory of their own ideology and their version of Islam).45Mamduh al-Mahayni, “Al-taknoqrati Ahmad al-Shara‘,” al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 7, 2025, https://aawsat.com/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%A3%D9%8A/5098672-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%83%D9%86%D9%88%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B7%D9%8A-%D8%A3%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%B1%D8%B9. At the same time these outlets have expressed frequent concern about “countries that embrace and feed the Brotherhood [“Ikhwani”] project” (that is, Turkey and Qatar) and the possibility that they could take Syria in an undesirable direction.46Mashari al-Dhaydi, “Al-Qaradawi… Khatar al-‘ubur fi al-Ziham,” al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 9, 2025, https://aawsat.com/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%A3%D9%8A/5099395-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%B6%D8%A7%D9%88%D9%8A-%D8%AE%D8%B7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A8%D9%88%D8%B1-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B2%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%85.

The pressures and leverage brought by their oil reserves brings us to the Saudis’ other core dilemma. After months of refusing to lower prices, they caved in to Trump’s pressures even before his visit to the region in May. Trump needs the Gulf to stick to this route to fight inflation at home, especially after the “Big Beautiful Bill” was signed into law in July, which will add three trillion dollars to his nation’s debt. In exchange for this concession, Trump acceded to Saudi desires during his Middle East trip, meeting with al-Sharaa in person, lifting sanctions, avoiding Netanyahu, and retaining a clear anti-Hamas line. The ultimate termination of the sanctions is conditional upon Syria joining the Abraham Accords and expelling Palestinian “terrorists”—two items that clearly indicate a Saudi diplomatic victory.47Despite the clear diplomatic advantages secured by the kingdom, its semi-official press still acknowledged Turkey’s persistent [co-]leadership of the transition. See, for instance, “Al-Safir al-Amriki lada Turkiyya yatawalla dawr al-mab‘uth al-khas ila Suriyya,” al-Sharq al-Awsat, May 26, 2025, https://aawsat.com/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%82-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A/5146581-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%8A-%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%89-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D9%8A%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%84%D9%91%D9%89-%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AB-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%B5-%D8%A5%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7. Moreover, Turkey once again became more central to the process from September to early November, hinting that the balance of power between the two sides are likely to fluctuate even more over the coming months.

Yet, keeping oil prices low over the coming years would seriously dampen the infrastructure overhaul bin Salman has been pursuing. The Saudis’ volte-face on oil prices was the cost of an apparently auspicious deal, as evinced by the pro-Saudi steps during Trump’s visit to the region. These diplomatic victories accompanied an economic one, as the allegedly “isolationist” Trump reversed Biden’s restrictive policies regarding technological aid and sales to the Gulf. Although this deal seems to make sense for the Saudis, it will likely narrow the popular basis for consent to domestic rule, since lower oil prices could undercut development projects, including the infrastructure and construction projects that are still the primary or secondary sources of livelihood for many people. The trickle-down effect of high-tech developments would be too slow to catch up with the social ills likely to result from contracting investments in construction and infrastructure.

These Saudi dilemmas have implications for Syrian capitalism too. While the emergent class structure is far from clear given the chaotic state of the economy, two processes must be noted: First, the transfer of wealth from Assad cronies to businesses connected to the new regime; second, Saudi-led Gulf capital’s oversight of the privatization of government lands and buildings to carry out a Dubai-like transformation.48“Syria and Lebanon: Crisis and Crossroads, w/ Nabih Bulos | Connections Podcast with Mouin Rabbani #108,” YouTube video, 1:02:23, posted by “Jadaliyya,” August 14, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V8kLirM6sF8. However, Turkey is also very eager to take on investments in the new Syria. It is too early to tell whether the Saudis can deal with their dilemmas and sideline Turkish capital in this competition. In either case, if the HTS regime is stabilized, the dominant class is likely to consist of al-Sharaa-connected capitalists and foreign Sunni business families—that is, a more dependent version of the Assad era’s oligarchic capitalism unlikely to take the material concerns of popular classes seriously.

The least noticed of these shifting balances has been China’s setback. Chinese capitalism depended on the smooth flow of energy and goods across the region as an essential part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Even though China had not made any substantial investments in the country at the time of Assad’s fall, the connection between Asian and European trade routes and energy lines afforded by Syria’s ports was central to the BRI. Cooperating with Syria, Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia, China wanted to minimize conflict throughout the region. This Chinese stance is not peculiar to the Middle East. Except in its own hinterland, the emergent giant has been trying to avoid acting as a new “hegemon” in the Arrighian sense: it refrains from combining an alternative ideological vision, an exportable “model,” and military interventionism.49Giovanni Arrighi. 1990, “The Three Hegemonies of Historical Capitalism,” Review 13, no. 3 (1990): 365–408, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40009226. If Arab states could build autonomous positions and trajectories, as some Chinese experts hope, this could potentially sideline Western, Turkish, and Russian imperialisms.50Jin Liangxiang, “Illusions Vanish in the Middle East,” China US Focus, March 20, 2025, https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/illusions-vanish-in-the-middle-east. Such a shift could indeed help China emerge as a “reluctant hegemon”—the only major capitalist power willing to increase consent at the expense of force as far as the Middle East is concerned.51This was Arrighi’s own hope regarding China, see Giovanni Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2007). Regarding the structural reasons why this is unlikely, see Ho-fung Hung, The China Boom: Why China Will Not Rule the World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231164184.001.0001. However, currently the only major actor in the region who has a pro-autonomy stance is the Kurdish movement, which (again, paradoxically) is forced by historical circumstances to rely on the most aggressive imperialist force (the United States) in the region.

For now, al-Sharaa’s unchecked powers are implicitly condoned by Western powers, even if the massacres of minorities are rendering tepid the warm reception of the salafi leader. Such complacence in the face of Islamic-presidentialism once again shows that—despite ongoing tensions between Trump and the neoconservatives, and secondarily between the United States and the European Union—the West never hoped for much more than overall stability for the Middle East combined with conflict-promotion whenever that aligned with the extractive agendas of particular states and firms. Dignity, bread, liberty, and social justice—the demands of the Arab Spring—will have to wait for the reorganization of popular forces. Neither the West, Turkey, the Gulf monarchies, nor an apparently “tamed” armed salafism can deliver them.

Photo Credit: European Commission

There is a narrative that al-Sharaa has changed his name, wears a tie, stopped promoting violence against people who reside in the West long before he took over Damascus, and that he therefore cannot be deemed a “salafi-jihadi.” But this narrative ignores the purposive and strategic fluctuations in the president’s past. Through switching back and forth for years between puritanism and pragmatism, cadre-building and coalition-building, violence and negotiation, he has for now attained one of his long-term goals: securing HTS rule over Syria. If his strategic wisdom in the past is any guide, he could swiftly switch to other tracks to attain some of his other long-term goals.

There is a widespread sense—shared by much of the right, left, and center—that HTS has transformed itself and is primarily oriented towards power than a religious mission. This might be the general direction where the organization is heading. But al-Jolani’s sharp swings in the past—back and forth between a violent puritan and a pragmatic power-broker—raise another possibility: al-Sharaa remains committed to the religious dimension of his political project too and will implement it when the opportunities present themselves.