Roundtable on China

A Dialogue between Lausan and Critical China Scholars

March 10, 2021

The following roundtable took place in mid-December 2020, involving members of the Lausan Collective and the Critical China Scholars group.

It centered around the question of how to navigate nascent US-China tensions and how to effectively articulate a leftist, internationalist framework of solidarity. In particular, we discussed 2 questions that have dominated headlines in recent years, and for which clear progressive positions have been difficult to stake out.

First is the rise of pro-China nationalist, or “tankie,” denialism of the detention camps in Xinjiang. Such denialism has become more popular in recent years among the Euro-American left. Last fall, Monthly Review platformed the internet denialist group Qiao Collective, which prompted an open letter by CCS to respond and critique.

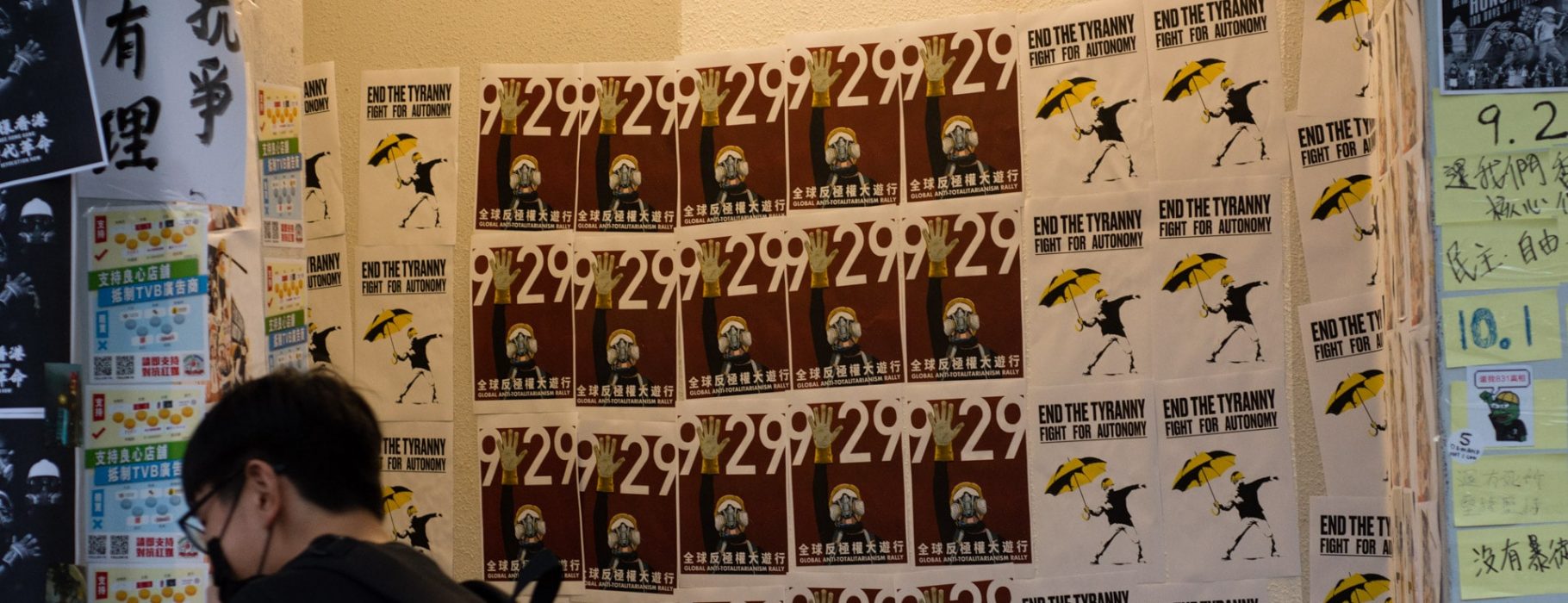

Secondly, we talk about political movements in Hong Kong and, in particular, how to challenge mainland Chinese state power while remaining critical of xenophobic, right-wing nationalism among the ranks of Hong Kong protestors. Why are Hong Kong activists so devoted to exclusionary nationalism? And where is the language of class, race, and international solidarity?

Lausan is a collective of writers, translators, artists, and organizers. Through writing, translating, and organizing, Lausan builds transnational left solidarity and struggles for ways of life beyond the dictates of capital and the state by holding multiple imperialisms to account. Lausan believes a radical imagination of Hong Kong’s future must center cross-border solidarity based on class struggle, migrant justice, anti-racism, and feminism.

Its members who participated in the roundtable were: S.R., Edward Wong, Vincent Wong, Alex, K.L., and Promise Li.

The Critical China Scholars are a collection of humanists and social scientists located around the world who specialize in the study of contemporary China and Chinese history. They came together in spring 2020 to counter rising nationalist tensions between the US and China and to offer progressive analyses of China and the world today.

CCS members who participated were: David Brophy, Aminda Smith, Fabio Lanza, Rebecca Karl, Andrew Liu, I.T., L.Y., and Daniel Fuchs.

ON XINJIANG AND THE LETTER

VINCENT WONG

We’re all pretty familiar with the [Critical China Scholars] letter that was published in response to Monthly Review’s platforming of the Qiao Collective’s resource list. I think it was very powerful coming from a group of critical academics.

I wanted to ask – I know Dave, this is your wheelhouse in terms of academic work – but when I was reading it, I was thinking about the disconnect that is constantly happening between a) what the left normally cares about and b) what is going on in Xinjiang. My question is what do we think are the preconditions in which we can frame analysis of what’s going on in Xinjiang, so that leftists can connect the dots. Because it’s not just the factual reporting. If it’s not kind of being easily digested in a rational narrative that can make sense to people, then I think we’re seeing where the kind of denialism, or weird coopting of state justifications, comes from.

DAVID BROPHY

I was reading something interesting by E.P. Thompson written in the 1980s, during the end of the Cold War. He had a nice way of summing up the political terrain at that time. What had happened during the Cold War was that, discursively at least, the causes of peace and freedom had come apart. So you had, on the one hand, the Soviet camp that was monopolizing the discourse of peace and then the US camp that was monopolizing the discourse of freedom.

And I think that that is kind of reflected in the state of affairs today. The tankies have gone out very strongly with this antiwar positioning, which of course is entirely appropriate. But you can easily see how geopolitics is kind of creating this divide [in which the Qiao collective monopolizes “peace” and the US critics of China monopolize “freedom”]. Obviously what E.P. Thompson was saying, and I think we’d all agree with this, was that those 2 causes need to be reunited.

So we need to understand the situation, both genealogically in the sense that this stuff does have a history. It has a history going back to Stalinism. The more proximate history here is the debate on the left around things like the Arab Spring, or the green movement in Iran. And I think we’re dealing with the fallout from that, as things move to China. The important connection is the way in which a lot of Islamophobic tropes that were generated initially by the West’s launch of the Global War on Terror have become assimilated to a certain extent in parts of the left on a sort of a third-worldist basis. All of this counterterrorism stuff is okay as long as it’s not the US doing it, as long as it’s someone in the other camp doing it.

For me that’s still a key point of intervention. When I talk about the War on Terror and Islamophobia, you can get pushback from certain circles on the left. They’ll argue that the situation is not just about that, that it reflects long term trends of China assimilating this region, and so on. Which is all entirely appropriate, but the question still is, at what point can people like us actually intervene around this kind of thing?

If we see our task simply as offering a left critique of the situation, then there’s lots of stuff that we can say about the nature of Chinese capitalism and so on. But we need to distinguish the task of critique from the task of intervention. For me, it made sense to try to highlight the War on Terror apologetics that follows from Xinjiang denialism. That’s the direction that we went in [with the open letter].

I don’t know exactly how the response has been, but it is I think [the link to the War on Terror is] one point around the Xinjiang issue where there is space for the left to intervene, and where there is an audience. Unfortunately, on a lot of the other fronts right now, with the liberal-conservative alliance that’s coming into being around the policies that the US is pushing, it’s difficult terrain.

My feeling having done that letter was that, for the time being, there wasn’t really a whole lot more to say. Going back to the whole peace and freedom thing, we do also very clearly need to position ourselves on the side of peace as well [as freedom]. So the tactical question of how we engage with that politics from this point on is going to become quite pressing too.

DIASPORA ORGANIZING IN CANADA

VINCENT WONG

The number one topic in Canada with respect to China is the Meng Wanzhou case. There have been “tankie” or “tankie” adjacent organizations involved. A campaign to free Meng Wanzhou.

It’s a little bit fraught ideologically, but it comes from a couple of places, not surprisingly “decouple from US imperialism” and “avoid the new Cold War” concerns about anti-Chinese racism – all those things. It’s a really strong entry point in Canada for this type of ideology to grow. Because it comes in the format of something that everybody can get behind, which is “say no to the new Cold War” and “yes to peace.”

Here’s where I would like to complicate the issue. Canada, like Europe or Australia, they’re a little different than the US. In terms of Canada, you wouldn’t be able to point to direct US imperialism as a reason to oppose x, y, and z. There will be times when Canada will have similar foreign policies, but then there will be times where they’ll detach from that. With the war in Iraq, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien very famously rejected that, and he had like this hilarious 8 seconds in politics [regarding what proof of weapons of mass destruction he would need to see to be satisfied with the claim advanced by the US as justification for the invasion of Iraq].

The problem is the discursive territory is so all over the place. When it comes to whatever a progressive foreign policy looks like, nobody knows what the hell’s going on. That’s where you have a place where the “free Meng Wanzhou” campaign [can grow]. [The campaign is] driven by a very tankie ideology, a very ultra nationalist historical revisionist idea of Chinese nationalism that denies Tibetan self determination, that sees China in this [image of a] kind of socialist utopia. What we’re trying to do is use what is going on in Xinjiang as an entry point into critique and understanding that, hey, China is ultimately not that different from any other nation state in a global capitalist hegemony.

If we see our task simply as offering a left critique of the situation, then there's lots of stuff that we can say about the nature of Chinese capitalism and so on. But we need to distinguish the task of critique from the task of intervention.

EDWARD HON-SING WONG

My experience [in Canada] was really frightening when I realized I think tankie-ism wasn’t just restricted to cyberspace with the internet trolls. It’s been really disconcerting, disorienting seeing a lot of comrades I’ve organized with for over a decade turn out to be tankies.

These are real people who are occupying leadership positions and doing important organizing work, whether in the labor movement here or in other social justice campaigns. In the past, we never had these conversations until issues around China became more prominent with the Hong Kong protests, with Covid-19.

It really came to a head around 2 years ago when we tried to organize a kind of global uprising rally here in Toronto, alongside Rojava activists, Latin American activists, Sudanese, and so forth. It was going really great until a big section of the rally led by the Chilean contingent had discovered that we were trying to organize a Hong Kong-China contingent. Right away they said no, we aren’t doing this, they pulled out, and the whole thing fell apart. Of course, there’s the more traditional tankie divide around Assadists saying they weren’t going to march with Syrian activists and so forth. For me, this was the first time seeing a rejection of Hong Kong-Chinese leftists in that space. It was quite alarming.

There might need to be a different response in terms of Internet troll-y tankie types versus what I’m seeing on the ground, in terms of when we’re talking to a lot of other racialized communities that are contending with colonialism. It might not be the same kind of bad faith actors that we see with Grayzone.

I don’t have the answers now, but I did manage to speak to a couple Chilean activists who did give me some time. For them, they couldn’t separate the images they were seeing of American flags being waved at Hong Kong rallies, they couldn’t separate the struggles that Hong Kongers and Chinese workers might be having from their own thoughts around needing to confront American imperialism as an immediate threat in their home regions.

MORE ON THE LETTER AND TANKIES

S.R.

I was wondering what you think was the reception of the letter from Indigenous Studies and Native American Studies scholars, who are influential on the anti-imperialist left. These people are left celebrities that have so much clout advocating for this brand of single-minded anti-US imperialism, rather than thinking about how any critique of US empire really needs to entail how the Chinese empire is in direct collusion. I’m curious how that letter played out in those circles.

What can we do to better bridge the gap between what we’re talking about – US counterterrorism and US-China state, elite-level collaboration – towards a more global and international critique of settler colonialism?

AMINDA SMITH

I think it was mostly ignored. Quite a few people shared the letter, but anybody who had any real clout just didn’t say anything.

FABIO LANZA

Even before the letter, I wrote directly to Vijay Prashad, and he never replied to me. I suspect that group is lost. I’m sorry to say, but I suspect that they are lost in this.

REBECCA KARL

The letter that we came up with was initially understood to be a way to reach across the aisle, not to try to antagonize from the very get go. Maybe they didn’t understand what the issues were, maybe they’ve been taken in, and maybe that was a little bit naive. Nevertheless, it was an effort to, an attempt for a certain kind of understanding and solidarity.

I think, with your suggestion to move the discussion into discussions of settler colonialism. The China field’s trope is of internal colonization, and I think that doesn’t do the same work as settler colonialism at all. So I think that that’s one way forward.

ANDREW LIU

I’m actually kind of approaching Fabio’s position that — we don’t want to take this subjectivist position of, well, if we just emailed them more, then we could convince them. These things are out of our control for reasons that all of you outline. This is their response to their perception of American empire, and it’s less about the actual details in China and Xinjiang.

ON PROMISE LI’S ESSAY ON THE FAR RIGHT IN HONG KONG

I.T.

I truly enjoyed reading Promise’s essay on the far right in Hong Kong, and I really appreciate the level of honesty and the genuine feeling in it. As someone who spent 4 years in Hong Kong, I can really relate to many of the experiences. Out of curiosity, how has Lausan been received among the left? We’ve all seen the Twitter fights. I worry that people who had the patience to read the essay still come to the conclusion, “look this [the Hong Kong right] is a necessary evil.”

At the end of your article you said there are basically just 2 options: to be a practical movement towards true democracy, or to just go back to those old cycles and different modes of entrapment. So another question is: what kind of concrete struggles for true democracy can we envision as a group or as a collective? And that’s also related to some concrete agenda, such as the labor issue in Hong Kong.

And lastly – and this is something I’ve never had a chance to share any of my thoughts on, as someone from the PRC – but I see so many parallels that we can draw between the Trumpists in Hong Kong and the Trumpists in the Chinese diaspora. So do you see any potential, a possibility of alliance across these communities, in my case in North America. Have any of these groups reached out to you?

Because I do see a nice entry point where all the Trumpists are kind of using the same rhetoric that we can confront as a united front. My personal take is, to be honest — as I said when I read your article, I was so happy because I do feel like the entire Hong Kong struggle for democracy has alienated a lot of people who are from China. This is just unfortunately the truth. But if we are to be realistic, the chances for Hong Kong to be able to use all the leverage between the two superpowers is getting smaller and smaller in many ways. China’s just so vast and powerful.

So I still see one of the hopes is to really change people inside China. I know it’s even more challenging, but I don’t see any alternative if you don’t try to make them a little bit more sympathetic to these democratic causes. It’s just a shame that many of us, people like me, having a Chinese passport cannot really express many of these things on the internet because we have family in China. But I see some hope there.

The fact that they don’t see us reckoning with our faults is actually limiting international solidarity.

PROMISE LI

On one level, I think it was a very emotionally driven piece. I felt like on the one hand it’s kind of coming from a personal place. But tactically speaking, it’s about what you’re saying, how the movement has alienated so many people and so many different international allies. In that sense, it’s important for a Hongkonger to come out against the right-wing and be as upfront as possible.

Hong Kong likes to hate on the left for being divisive and because we’re always critiquing things and that we don’t actually do anything. But I think this essay has actually won over more international allies, to help them understand the complexity of the struggle. In the end, I’ve earned more ire from the movement itself.

I think so many people have excused the right-wing elements as a kind of politics of desperation. So many people in the movement saying, “no, no, people aren’t actually right-wing they’re actually pretty liberal, but like we don’t have a choice and Trump’s our best option.”

Where this starts becoming a problem is when you see this becoming a politics of enjoyment, and no longer simply desperation. You see Hongkongers actively going beyond the bounds of what’s necessary to defend Trump and to defend that rhetoric, and how that comes so naturally. The point is that this isn’t just disinformation or that Hongkongers are just duped. That’s an easy and simple way to create Hong Kong as kind of a pure victim or passive victim to far-right campaigns. I’m trying to stress that it’s something that’s deeply rooted and to foreground Hong Kong’s identity and its proximity to Western colonialism and Western values that I think the city has never unpacked. The love for Trump’s platform and the love for that type of politics actually ends up overriding concrete things that can actually help the movement, which is what everyone valorizes.

I always go back to this moment when we did our BLM-Hong Kong exchange in the summer. There’s this moment when Tony Wong, one of the speakers, had a moment when he knew he needed to address the rising Trump element, and he was just like, “I’m really ashamed for the movement, and I can’t believe I have to address that now there are a lot of Trump supporters, and it’s really terrible.” It’s hard to bring that up, especially in a talk with a bunch of people who are directly impacted by Trump’s policies. There were like 10 comments saying, “hey we really appreciate that you said that.”

I think one thing many Hongkongers don’t quite realize is that self criticism is such an important tool, not only in principle — that this is something we have to reflect on when talking about democratic values — but also a really important strategy to reach out to international allies. The fact that they don’t see us reckoning with our faults is actually limiting international solidarity.

Liberals in the diaspora were one of the big audiences. It’s not just about trying to change the minds of the far right. I think the big question I pose is what to do about the fact that the centrism, the bipartisanship, the liberals are the ones pushing the dynamics that have enabled the rise of the right-wing.

In terms of concrete solutions, students in the diaspora are a huge pool of people that I don’t think the tankies necessarily have a monopoly on. For us, there’s actually a lot of opportunities with labor groups, students, and other community allies like Chinatown groups. I think there’s actually a lot of leeway for us to push this platform. I think the work is already being done. I think CCS’ educational series is super important. It’s about how we can connect to people like Helena Wong, Toby Chow, Alex Tom, folks who are based in these different activist communities, how can we plug our work into their networks because I think building trust is so important.

ON CLASS, UNIONS, AND ORGANIZING IN HONG KONG

L.Y.

I’m really curious why in Hong Kong the language of class has just been completely elided from a lot of the movements. In Promise’s piece, he mentioned it doesn’t matter who the right wingers are in particular, but these voices are there and we on the left have to respond to them.

I am really curious who these particular people are, because I see an intergenerational divide, that the Hong Kong youth are dealing with the problems of capitalism, that’s very different from, say, the 60s or those in the 70s. Housing is a real issue in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is one of the most unequal cities in the world, and the disenfranchisement of the youth is a real thing. In light of these divides, why is it that the language of class, and gender and race, are just completely not there.

VINCENT WONG

A lot of it has to do with the experience of 2014 and the failed Umbrella Movement, the “pro-democracy” Occupy strategy. The consensus that came out from many oppositional camps was, “Hey, we have to put the question of class aside for now, in order to build a big enough tent to defeat the government.”

So the class issue is obvious, it’s there. Hong Kong is a textbook example of when neoliberal economics meets authoritarian politics. Twenty percent of folks are living in poverty in this incredible city of wealth. Housing prices are the highest in the OECD. So this is pretty obvious. And even when you see a lot of the students and young people who are part of the front line or very active in the movement – a lot of them are super precarious, precariously housed or even homeless in certain cases. The movement itself had to have people take people in essentially who were de-housed. The class critique is always there, and it’s always a driver, but because of this tactical decision, it can’t really be criticized. If you put that out there, then you’re undermining the movement. The space to have that conversation is not there until the movement either ends or runs out of steam.

S.R.

L.Y., as much we need a robust critique of the Hong Kong far right, we also need a really strong takedown of liberal citizenship as this constitutive element of nativism and exclusionary types of nationalism. There’s so much personhood stuff going on in any discussion about liberal democracy that by default there leaves no room for any prioritization of like racialized people, migrant workers, sex workers, etc. For me, it speaks to the danger or, I guess, the challenges of the labor movement in Hong Kong at this moment.

It’s been a year since the unionization wave has really kicked off. The hospital workers in Hong Kong launched a strike and organized co-workers in a way that’s unforeseen and was impressive to other people. However, it’s uncomfortable to talk about how that sort of mobilization has been around this anxiety of closing the border to mainland China.

Nobody really wants to talk about how the labor movement is really picking up steam, and it’s like very exciting, no one really wants to talk about how the underlying current or overarching consensus of liberal citizenship still produces Sinophobic, exclusionary tactics.

It ties into the whole movement context of tactics. What is the most direct way – what is even celebrated as – a way to get rid of Chinese encroachment. People right now see the union movement as a hindrance, as one of many fronts of a decentralized movement, rather than something that has a really united impetus and pushing forward.

We do need to embrace the radicalism. This stuff does push you towards a situation where you do actually have to envisage a kind of a revolutionary situation in China to start talking about an alternative.

DAVID BROPHY

My sense is that this is all generated by the strategic logic of the situation and what appears to people as the horizon of the politically possible in Hong Kong. A lot of Hong Kong politics has been a negotiation between capital and the Chinese state, and a lot of people put their hopes for preserving things like rule of law, civil liberties, on the preservation of Hong Kong as a particular kind of business environment. Those two things go hand in hand for people. I still think there’s still a lot of hope in that direction.

On the other hand, you have a sort of more radicalized version of that, which is this hope that capital will now pull out and trigger a collapse and that will flow on to the rest of China. But that’s just a radicalized version of that same paradigm in which capital is positioned as an ally. So anything that jeopardizes that alliance or that might push capital towards compromise with the Chinese state – which, we all know it will compromise – but nonetheless we do have to just recognize that there is this structural logic here. Any amount of agitation in the current environment, where possibilities like saying, “Well, let’s link up with the mainland” is just, there’s only so far you can get with that kind of approach.

It means we do need to embrace the radicalism. This stuff does push you towards a situation where you do actually have to envisage a kind of a revolutionary situation in China to start talking about an alternative.

You see it in Western governments still today, this hedging. On the one hand, hinting at the possibility of pulling out but also this traditional approach of trying to stabilize Hong Kong and preserve Hong Kong, as it has been for the last two decades. I mean certainly Australia’s position has definitely lent in that direction. We signed a new free trade agreement with Hong Kong last year. So people can have this idea that that’s still a way to make sure that China fulfills its obligations and so on.

L.Y.

I think that the Chinese diaspora, especially those that are from the older generation that have immigrated out of China, Hong Kong in the 70s, 80s, are certainly invested in unhinging that type of investment, either in mainland China or in Hong Kong. But I think that introduces a whole other set of intergenerational and racial dynamics, because those people have immigrated abroad, have a bit of capital to have immigrated out in the first place.

DANIEL FUCHS

If we look at the so-called unionization wave that has happened about a year ago or so, has there been any actual sort of changes in the discourse and in Hong Kong on the class issue? I got the impression that we started with the premise that class discourse was non-existent and that we have to do something about that. But the unionization drive has been ongoing for a year already, so has there been any changes in what is happening on the ground? Another question is if you could give us a description of the situation regarding labor organizations in Hong Kong that used to be active on the mainland? What is their current situation given the National Security Laws?

K.L.

The old union movement of Hong Kong was very much identified with the Communist Party of China, identified with the mainland. So there’s a natural reaction against that. What I think has been really good with, HKCTU, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, is that it has always had a really nuanced perspective on mainland China. Some of their leaders very much have the idea that only if China can democratize can Hong Kong have a progressive future. They have a very nuanced critique of mainland China, and at the same time they counter anti-Chinese sentiments.

At the same time, they very much submerge themselves in a liberal discourse. So even HKCTU, which does really good organizing work, their discourse is mostly liberal-democratic rather than class based. And that means there is a lot of good organizing at the workplace level, but I don’t even see class discourse emanating from HKCTU, not much anyway.

And then with the new unions, they have this funny relationship with HKCTU. HKCTU is trying to organize and provide support and training. But there’s a lot of internal conflicts among the new unions, and some of the new unions distrust HKCTU because of their affiliation with the pan-Democratic camps. So it’s very fractured at the moment. And also the reason there was such a big drive, such a big effort for unionization, was for the purpose of the election, for the legislative council election. But because that’s been postponed, the new union movement has sort of lost its focus.

They are also up against this obstacle of renewing membership. It’s been a year, a lot of members are not renewing their union membership, so how do you even deal with that? And of course there are logistical issues in terms of, the Union membership fees are low, like $20 a year per person, so they can’t even really afford to have full-time organizers. So there are all these practical challenges, along with the national security law. So all these practical challenges mean that the new union movement, which was really impressive, is having a really difficult time consolidating themselves at the workplace level.

Finally there are a lot of labor NGOs that you mentioned, which are extremely important in supporting the labor movement in mainland China. From what I‘ve heard, their staff has already stopped going to mainland China as of last year, since the protest movement started, just for security reasons. Obviously the repression started way earlier against mainland activists, and so there’s been a slow shift among the labor NGOs in Hong Kong working on mainland issues. They are not sure what to do next.

It does sever those ties that we used to see between the labor movement in Hong Kong and the labor movement in the mainland. We’re trying to work through what that means, and with the border closure, we’re not really traveling back and forth between Hong Kong and mainland China, so the actions are kind of lost for the moment. But the hope is we’ll be able to do something once the pandemic situation is under control, and we can try again.

S.R.

I think a good case study for your question, Daniel, is the specific unionizing around grassroots workers like sanitation workers, cleaning workers, logistics, that type of stuff.

For Hong Kong, the majority are actually mainland Chinese women and also South Asian migrant workers. A number of barriers prevent them from participating in the movement, and there are also difficulties in terms of how to organize with someone who doesn’t know about the movement? How do you organize with someone whose economic precarity makes it difficult to think about the intersections of the pro-democracy struggle and the union? For a movement that has largely sidelined class questions, this dynamic is still happening even on the level of unionization.

Another thing I think that we need to watch out for is that there’s no one size fits all, wholesale application of labor advocacy that can really solve the problem of how to do away with all these right-wing conservative tendencies in one fell swoop. So in that sense, in order to achieve the structural overhaul that we need, the union movement might think about starting from a smaller scale workplace by workplace basis rather than jumping straight to thinking about things on the basis of sector.

We’re trying to work through what that means, and with the border closure, we’re not really traveling back and forth between Hong Kong and mainland China, so the actions are kind of lost for the moment. But the hope is we’ll be able to do something once the pandemic situation is under control, and we can try again.

ALEX

I agree with the critiques and concerns by others, what K.L. said something about the discursive distinction between a class-based one and a more liberal democracy one. There are some new books written on Hong Kong’s union history, published a few years ago. Independent unions only started in the 80s, so it is pretty new. And when the unions entered the 90s and the 2000s, well, they were already struggling. They had to deal with the question of how to organize when Hong Kong, by then, was already undergoing a transition from an industrial city to a more service and finance-based city. Many of the union organizers, if you talk to them, they say it is really hard to organize workers, because you no longer have an industrial base in Hong Kong. So that’s one major narrative shared by many organizers from the union.

Many union organizers in Hong Kong, in the 1990s and 2000s, they moved to mainland China to join the union movement there, because they saw there were more opportunities in China than in Hong Kong. But starting from the early 2010s, many of them have moved back because you have less room to really organize labor in mainland China.

Another dimension is: what happened last year was really new. It was a new experience for many organizers in Hong Kong. They are also learning how to organize in the finance sector, in the nursing sector.

In the 1990s, there was a lot of debate between the grassroots activists about whether they should stay outside or go into the Parliament. It was right after the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre, so people were really struggling with whether it would be more strategic to stay out of the Parliament or go up for election. It turned out people decided to go up for elections because of the economic changes in the 1990s and 2000s in China and Hong Kong. So perhaps a more political-economic analysis of the dynamics would be needed, but that is only on the analytical level.

Circling back to what Andy mentioned earlier, how to speak to the audience on the ground, that is really challenging. We place a lot of value on Promise’s article, but it has very little purchase in Hong Kong. If you circulate Promise’s article in Hong Kong, then right-wingers would reject it outright. That’s expected. For the left-leaning people, they would say it needs a lot of translation to make it legible. Much of the vocabulary used in western, left-leaning discourse is not really accessible to a Hong Kong audience. You do need a lot more contextualization, vocabulary translation, to reach more of an audience.

That is one of the challenging parts, you need to provide a lot of context to make your critique make sense. Otherwise, it is really hard to go through many of the [language, cultural] barriers, and otherwise you just stay in an echo chamber. So that is probably one of the biggest challenges facing left-leaning people in Hong Kong and beyond. How do you bridge that gap and make that translation legible?

That would really be a strategic concern for many. But folks can only test it out by writing more and providing more history, [that] might be a way to go. If you look at some of the debates online in Hong Kong, many of the debates lack historical depth. They don’t really understand the history. If you could tell the story by providing a more complex picture and filling a gap, then that might also help. But that would need a lot of research and reading, and that is perhaps one of the collective projects that folks could work on. I think that is important, because that is part of the process of decolonization, to re-educate people about how to analyze dynamics from another perspective.

K.L.

Thanks Alex, I actually have a question for you on your last point.

I know you write in pretty mainstream media [in the US]. I wonder how you frame your own positions, because you’re speaking both to a mainstream audience in the US, but also you will think about how your writing is perceived or received in Hong Kong. How do you navigate framing your own ideas and politics and positions while at the same time speaking to two audiences.

ALEX

I would say, I don’t really know how to speak to the left-leaning audiences in the Western world. I think that is one of my limitations. I am most sensitive to the language used in Hong Kong, so I can avoid some of the traps there, I think that’s my advantage. But how to bridge audiences on both sides? I think I need some navigation. I think that is one of the challenges facing myself. That’s why I feel like Lausan and CCS are really crucial platforms. Because you need to immerse yourself in different communities so as to absorb their language, to be more alert to how language and vocabulary are used, so as to make the critique legible to different audiences.

I feel like that might take a long time, and perhaps that’s also part of the collective work. So I’m also learning from folks here to see, what are some of the concerns and some of the some of the talking points raised by folks, and how those talking points could be translated in Hong Kong’s context by using more local vocabularies that could be understood by local people.

So I feel like there might be like multiple fronts that people are addressing at the same time. I don’t, I don’t really have a concrete answer, but I feel like it’s rather like a learning journey for me as well.