Seven horns blowing? An orange devil at the door? In what they make clear is no less than a battle for humanity’s soul, Adam Turl’s must-read Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted from Heaven & Earth deconstructs capitalist entrenchment in the art world and beyond. Turl is more than an art theorist, and their new book should be appreciated in light of their prolific artistry, Marxist theorizing, and firebrand analysis of culture and politics. They are the cofounder of multiple contemporary projects, including the Locust Review, LALC (the Locust Art & Letters Collective), Locust Radio, the Born Again Labor Museum (BALM), and was also an editor at the former Red Wedge publication. Together with their partner—the activist, poet, writer, editor, podcaster, and artist Tish Turl—they have taken on the causes of labor, revolutionary politics, collective organizing, and art production in Southern Illinois and elsewhere for many years. Quoting critic Laura Mulvey, they note, “moving from oppression and its mythologies to a stance of self-definition is a difficult process and requires people with social grievances to construct a long chain of counter myths and symbols.”1Adam Turl, Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted from Heaven and Earth (Revol Press, 2025), 86. That would describe Turl’s own artwork, their efforts within the Locust Review publication, and their organizing work in general, where calls for art and writing seek to draw out and build upon these counter myths and symbols. Gothic Capitalism is a theoretical explication of their own processes and aspirations, and they give us a window seat.

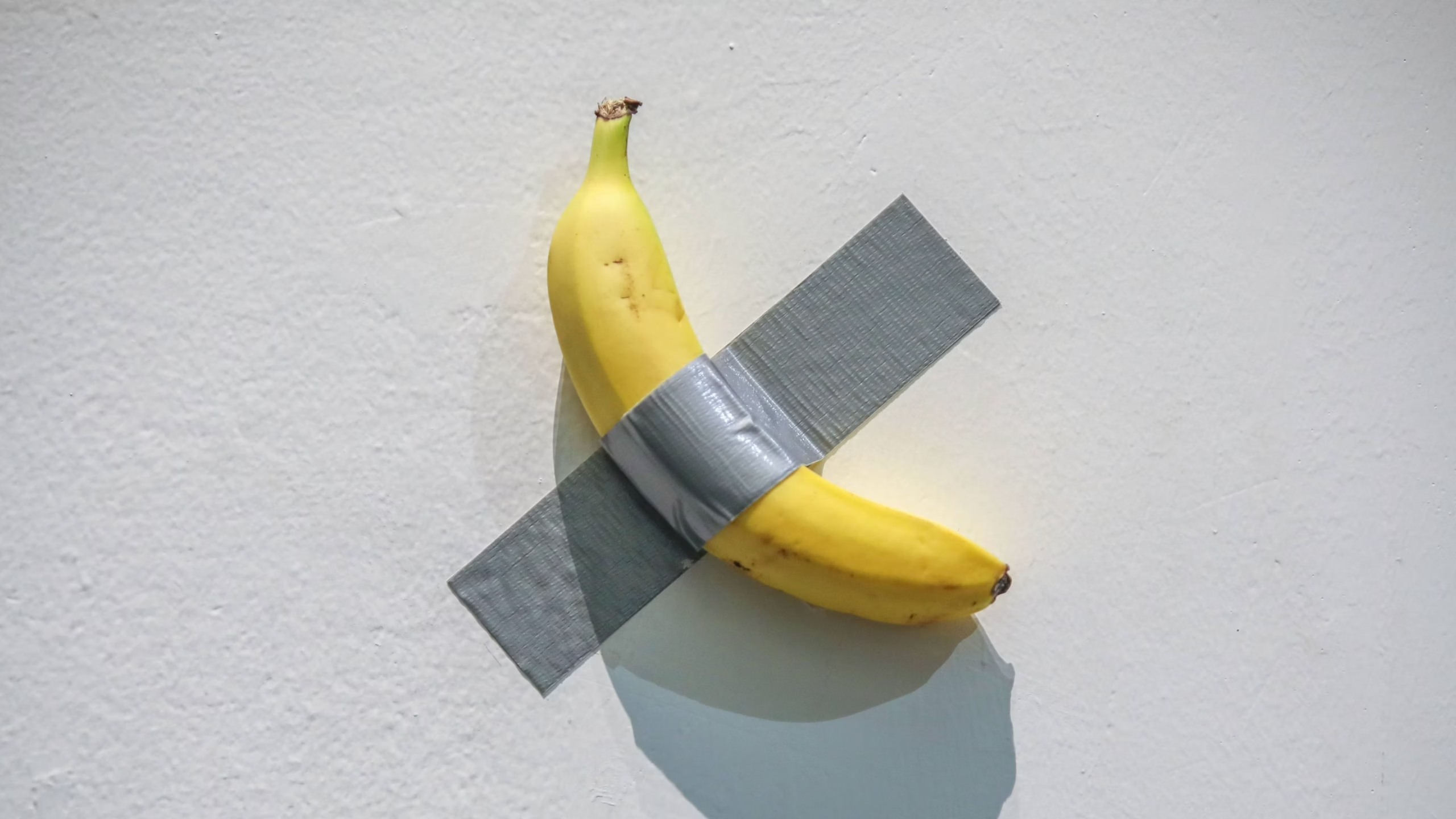

Given Turl’s broad and radical commitments, they are well-positioned to identify dynamics within the art world so as to declare mutiny, calling—through their particular Marxist lens—for a renewed commitment to the promises of spiritual and material progress. Turl illustrates how both the voracious appetites for the next alternative trend so valued within today’s art scene and the apathy and indifference toward high art within the general population are part of a decrepit late-capitalist theatre of damnation—art that is Evicted from Heaven. Without a revolutionary soul (from below), the “art” of the “established marketplace,” the “canonical art museum,” and the “academic avant-garde” become the “historical debris of bourgeois society,” refracting “capital into cultural objects and concepts.”2Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 19. It is the content-vague spectacle of a “weak avant-garde” that leaves the spectator “starved for anything that actually says something.”3Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 109. Turl’s notion of a “weak” avant-garde is quite helpful. Case in point, what does the sculpture “Comedian,” by artist Maurizio Cattelan—–the infamous banana duct-taped to a wall that sold at a Sotheby’s auction for 6.2 million dollars in 2024—actually say? Its price—its commodification—certainly becomes part of the spectacle, supplanting content. Aptly, it is a piece of food that cannot satiate.

Turl goes on to explain the concept of the weak avant-garde thus, “[i]n modern art, conceptual, stylistic, and formal innovation could seem to parallel social progress. [But] we no longer have an avant-garde guiding us with its beacon. It is up to the working class to regain that potential in culture and to emerge from the uneven development of [G]othic capitalism.” The meaning of Gothic in the book runs a gamut of descriptions that may be difficult at times for readers unfamiliar with the concept to pinpoint. Turl became interested in its usage after encountering author China Miéville in Chicago in 2013. The Gothic would seem to include the “ruins of the past” looming large, and the present—anachronistic and dislodged—is a combination of the past and future’s potential and losses. There is so much more to it, and referencing Miéville’s thoughts on the matter is useful; they talk about a Gothic Marxism being a realm where solidarity with the outliers, debris, and monsters produced by capitalism can be a way of advancing a dialectical approach between the rational and irrational. It seems fair to say that, inversely, Gothic Capitalism is where “’dialectics is at a standstill.’”4Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 22.

According to Turl, the United States has become as Gothic as the Old World, “living in the defeats of liberation struggles and within the limits of tyrannical ‘realisms,’” among them “capitalist realism” as examined by the Marxist theorist Mark Fisher.5Turl, Gothic Capitalism, 15; Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative (Portland: Zero Books, 2009), available at https://files.libcom.org/files/Capitalist%20Realism_%20Is%20There%20No%20Alternat%20-%20Mark%20Fisher.pdf. While their insights are deeply penetrating and intriguing, the reader could always benefit from some further unpacking. At times, they appeal to a very broad readership. At other times, to those who would have a more detailed understanding of art and history, requiring some readers to do more digging—which, obviously, isn’t a bad thing. At intervals, one wants to ask Turl for more detail about some of their historical and theoretical musings. Nonetheless, their clarion points, as will be discussed here, very much deserve to be reckoned with and digested.