From Schlemiel to Super Hero

Volodomir Zelensky and the Price of Western Inclusion

March 18, 2022

As Russia invades Ukraine, Jews find themselves yet again conscripted into the West’s fantasies of itself. On March 1, reports came that Babi Yar, a major memorial of Judeocide in Europe, had been destroyed by Russian missiles. But while Russia’s bombs had hit a nearby communications tower, they did not in fact hit the Babi Yar memorial. The story’s prominent media coverage and its emotional charge are emblematic of how this war mobilizes Jewish memory. For his part, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly invoked the need for “de-Nazification” as a pretext for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. One may debate the Azov Battalion’s and fascism’s role in producing the conditions for this conflict and in the historical formation of Ukrainian nationalism more generally. However, it remains clear that Putin wishes to press strong cultural memories of the German blitzkrieg into service as legitimization for his own illegal invasion. Despite some Jewish Studies scholars such as Enzo Traverso and Marc Dollinger who persuasively argue that the formation of a Jewish state and the assimilation of Ashkenazi Jews in the United States have ended the phase of Jewish marginality, the ongoing perceptions of Jews’ “otherness” apparently remains politically useful to those in power.

Nowhere is this projection of Jewish history more salient than in the person—or perhaps the body—of President Volodimir Zelensky himself. Elected in a popular landslide as a political outsider, his promises to clean up endemic corruption in Ukraine and to end the war between Russian-speaking separatists and Ukrainian nationalists in Donbas region garnered him wide popular support. It has been noted how much the scripts of Servant of the People, the satiric TV political comedy Zelensky wrote and starred in, prefigure his actual life: Vasyl Petrovych Holoborodko, a bumbling, underpaid schoolteacher who attempts in vain to get his mother to iron his shirt, is elected president after he makes an anti-corruption rant that goes viral after being surreptitiously recorded and shared by a tech-savvy student. Vasyl’s transformation from schlemiel to a serious man, as he accepts his duties as president, seems to mirror Zelensky’s own transformation in the Western media from feckless actor to war-hero.

Americans seem to want a virile ubermensch who can stand before the bombs as a knight errant.

For U.S. media, Zelensky’s attempt to responsibly thread the needle between Ukrainian sovereignty and a complicated, multi-ethnic nation met with unbridled scorn. In a widely reprinted guest column in the New York Times, Zelensky was described in the weeks leading up to Russia’s invasion as “in over his head.” Zelensky’s attempts to defuse the crisis that now engulfs his country were not understood as the quality of a responsible statesman, but rather “dispiritingly mediocre,” more of a “showman” and a “performer” than a serious national leader. Yet weeks later, Zelensky’s transformation from schlemiel to martial hero seemed complete. From the New York Times to MSN to the Washington Post, Zelensky was reborn not only as a war-time leader, but as a man who could “unite the world” as a “symbol of bravery”; his line, “I need ammunition, not a ride,” is read as action-hero bravado rather than self-deprecating comedic satire. Comparisons between Zelenksy, Putin, and Trump only underscore how much the question of manliness is at stake in leadership: Zelensky is undoubtedly a courageous person in an impossible situation doing the best he can, but to suggest that his actions are a replacement, or should be read as a replacement, for the masculine power of Trump and Putinsuggests how much Zelensky’s gender, and not just his politics, is the question at hand. It is one thing to be a leader in a time of crisis; yet Americans seem to want a virile ubermensch who can stand before the bombs as a knight errant. That Zelensky has also become a global sex symbol merely adds a layer of the absurd to the already incredulous.

As Time Magazine framed it in a rather revealing metaphor, Zelensky has been remade from “Charlie Chaplin

” to “Winston Churchill.” The comparison is not only revealing insofar as Churchill was a flaming antisemite and Western chauvinist, but Chaplin, who played Jewish characters and was often derided by the right in antisemitic terms, was often thought to be Jewish himself and may have actually had Jewish roots. Regardless of Chaplin’s actual identity, as Hannah Arendt argued, his most famous and identifying role as “The Tramp” carried with it the entire history of Yiddish theater and a Jewish sensibility of the pariah, existing between borders of identity and in the interstices of orderly society. One might say, Zelensky has been baptized by fire.

Jewish-American and Israeli media have also noted the Jewish dimension of Zelensky’s transformation. Yet, rather than engage with subtlety and nuance, they have transformed him less into a literal Anglo-Saxon, and instead into a muscle-Jew, a figure of Jewish martial vigor and strength. In an article in the Forward, Zelensky was praised as a “modern Maccabee,” referring not only to ancient Judean zealots, but to the Zionist cultural myth of the “New Jew” who triumphs over Jewish enemies real and imagined with military prowess and masculine courage.

The image that often accompanies Zelensky-as-Maccabee is not of him in his usual attire—a casual suit or his post-invasion olive t-shirt and blue-and-yellow pin—rather, it is of him striding out of a military jeep, dressed in a flak-jacket, army helmet in one hand. The Atlantic raises this note an octave to say that Zelensky’s “fighting spirit” is actually the terrain on which Jews will find “acceptance and inclusion” in the West, which of course implies the converse: to the extent that Jews resist such conscription into Western ideals of manhood, they will remain perpetual outsiders. The pro-Israel non-profit, Jewbelong, forced this association into barbaric clarity: in a tweet with the now-famous image of Zelensky in a flak jacket, he is opposed by the equally famous image of Bernie Sanders in mittens and a surgical mask, with the caption: “Which kind of Jew are you?” That Sanders’s crossed legs, medical mask, oversized orange mittens, and look of physical discomfort during a presidential address are contrasted with the casual manly stride in a military uniform says far less about Sanders and Zelensky as people than it does about the fantasies projected onto Jewish identity—particularly Jewish masculinity.

For victims of the Nazi Judeocide, Israel's U.S.-supported success burnished both the U.S.'s story about itself as liberator of Europe's oppressed, and proved martial vigor had a legitimate and legitimating role to play in the world.

As Jewish Studies scholar, Daniel Boyarin, narrates in his seminal Unheroic Conduct, there has been, half constructed and half real, a stark binary between Jewish and Christian ideals of manhood. As Boyarin historicizes from medieval Europe to the present, the Ashkenazi Jewish ideal of “Edelkayt” has long offered the gentle, timid, and studious male of the Yeshiva as a Jewish model for masculinity, one that has been secularized into the figure of the “mentsh.” This ideal Jewish manhood was explicitly contrasted with both Roman and later Christian values of masculinity that interpret “activity, domination, and aggressiveness as ‘manly.’” From Freud’s narrative of a Jewish father who allowed his yarmulke to be knocked off by an aggressive and antisemitic Christian, to Passover haggadot that depict the “righteous son” to be a scholar and the “wicked child” to be dressed in Roman robes with sword, the “soft man” often quite self-consciously was celebrated against the “knight in shining armor” of Christian myth. Of course, Boyarin is at pains to point out that there have been Jewish warriors, but that dominant diasporic Ashkanzi culture not only frowned upon such activity, it invented “soft masculinity” as a counter-tradition. The bookish, non-violent, “sweet and delicate” Jewish man was seen as both responsible and sexually desirable. “As it developed historically,” Boyarin concludes, “diaspora Jewish culture had little interest in Samson, and its Moses was a scholar. . . even the Maccabees were deprived of their status as military heroes.” As Boyarin himself states, he thinks of his own “sissy” lack of adherence to dominant masculine ideals as not so much “girlish” as positively “Jewish.”

Jewish ideals of masculinity have changed a great deal since the mid 20th century, as Zionism has risen in cultural and political ascendency. This is not to say Zionism is the only cultural model among Jews. The zealous praise of Zelensky as a “Maccabee” suggests that there may be some anxiety among Jewish nationalists that such a manly, Christianized ideal is not necessarily widely shared: one does not need to make propaganda to convince people the sky is blue. Yet this cultural celebration of Zelensky’s newfound manliness fits within a Zionist cultural framework that understands masculinity as part of the redemption of the Jewish people into their new state. Zionism, as an historical project, was, as Boyarin chronicles, not just a solution to the Jewish national question, but was also intended to redeem the “soft man” of the diaspora and transform him from his “state of effeminate degeneracy into the status of. . . a mock Aryan male.”

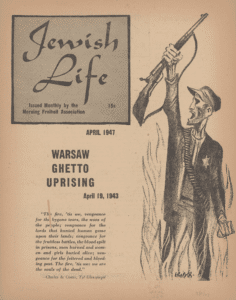

For Zionists such as Herzl (and, more recently, Binyamin Netanyahu) the lesson learned from the Holocaust, and from antisemitism more generally, is that diasporic Jews were weak, this weakness derived primarily from flaws inherent to their culture, and they perhaps tragically, perhaps poetically, deserved what fate was handed to them by their lack of military strength. One can see this transformation in memorials of the Holocaust in the years just following the war: representations even of Jewish armed resistance tended to show the Warsaw Ghetto fighters as ghostly specters, as women and children, rather than the masculine shock troops that would accompany later representations. This is not to suggest that Zelensky is motivated by Zionism in his defense of Ukraine any more than any single posted thirst trap of Zelensky lifting weights (yes, lifting weights) is motivated by Zionism. But the chain of associations from diasporic effeminacy and the transformation of Zelensky’s initial image in the West as a schlemiel into that of a Maccabee carries an often deliberate reference to both the Holocaust and the strong, virile Jewish state as its cultural redeemer. One can argue that Zelensky has been transformed discursively from a Jewish “sissy” into gentile knighthood.

The role of wartime Jewish history and Western imperialism is, as many have noted, entangled. Not only has the U.S. legitimated its expansiveness as an empire through its shared victory over Nazis in WWII, the figure of the New Jew emerged to form a now crucial part of the idea of the West. As Paul Hanebrink writes in The Specter Haunting Europe, to the “Judeo-Bolshevik” who so animated right-wing propaganda was supplemented, by liberal Cold War intellectuals, with the equally totalizing myth of the “Judeo-Christian” West. For victims of the Nazi Judeocide, the U.S. supported success of Israel served to burnish both the U.S.’s own story about itself, as the liberator of oppressed of Europe, as well as to prove that martial vigor had a legitimate and legitimating role to play in the world. As the bellicose Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a speech after his nomination, his father knew only three words in English when U.S. soldiers rescued him from a Nazi concentration camp: “God Bless America.” “That’s who we are,” Blinken asserted, “That’s what America represents to the world, however imperfectly.” America’s legitimation as Jewish liberator was solidified by the almost unanimous support for Israel’s triumph in the Six Day War. Not only was it seen as a final Jewish victory over the Holocaust, the lightening battle was offered as lasting proof that the IDF could do what the U.S. marines in Vietnam could not: win swiftly over its enemies in the clean, clear light of the Arabian desert. As Melanie McCalester and Amy Kaplan note, the 1967 victory was not only a victory of East versus West, but an incorporation of Israel—and the New (military) Jew—as the elite commandos in a clash of civilizations. Saving Jews, and remaking them into proper gentile men, one could say, has been a vision of Jewish life not only among Zionist radicals, but also among American Jewish and non-Jewish imperialists alike.

It is clear that for Putin, as for Cold War imperialists, the story of the defeat of fascism has been just another way to legitimate his own form of extra-territorial domination.

Complicating the orderly Jewish progress into Western forms of masculine nationhood has been the re-emergence of the far-right on the global stage. From Charlottesville, Victor Orban, the Azov Battalion to Putin’s own Russian Orthodox nationalism, “Jewishness” has become yet again a means to narrate the collapse of liberalism and its normative inclusion of minorities into its framework. Putin himself trades on the long memory outside of the U.S. of Soviet resistance to the Nazism, as well as to Cold War anti-communism and imperialism. Yet as seen through a glass darkly, it is clear that for Putin, as for Cold War imperialists, the story of the defeat of fascism has been just another way to legitimate his own form of extra-territorial domination. U.S. support for the state of Israel, with its own fascist movements, can be no more seen as antifascist, or pro-Jewish, than Putin’s own claims to be a bulwark against Western chauvinism or the far-right.

This conscription of Jewish masculinity and the Holocaust into stories of U.S. imperialism, Zionism, and Russian military aggression, however unfortunate, thus must also be seen as a key way the West, broadly conceived, narrates itself well into the 21st century. While many Jews from the U.S. to Israel embrace these narratives, it should be remembered that these are narratives that also erase actual Jewish complexity. As my Ukrainian-Jewish-American friend and colleague Maggie Levantovskaya posted on Twitter, relationships to Ukraine for the many American Jews, including myself, who can trace their ancestry there, are complicated: there were, as she said, Jews who wanted to flee Ukraine; Jews who lost their family there; Jews who remained there and feel it is their country; and Jews who married Ukrainians, who are now Jewish American Ukrainians. There are also, including in my own family, Jews who associate Ukrainian nationalism with fascism and who regard President Zelensky with a speculative wonder.

Zelensky’s own relationship to masculinity and to Jewishness are complicated. For instance, in one of his sketch comedy acts before becoming president, he imitated playing a Jewish folk song with his penis. This comedic and satirical act can be read much like the way Jews are asked to relate to Jewish history: with what part of phallic military life will it be played? Even as I write, Zelensky has survived three assassination attempts and I wonder if he will be alive when this piece is published. It is a chilling and awful thought to have Ukraine’s first Jewish president deposed or even murdered at the barrel of a gun. While I have no idea what Zelensky himself feels about his newfound role as savior of West and America’s thirst trap; it is entirely possible he will lean into it as a means, conscious or unconscious, to save his country and his family. Yet his reinvention from untermensch to Maccabee means that he has never really been seen, nor could he be seen, any more than the complexity of Jewish life in Slavic countries can be seen for all the contradictions it inhabits. I fervently hope this war will end soon and Russian troops will return back to their country of origin; that Ukraine can rebuild what has been destroyed and that both Russians and Ukrainians can mourn their dead. But the misrecognition of Jews and Jewish history, aided or not aided by Jews themselves, means as always, that people in power or who want power, never see themselves, or the people they wish to conscript into their plans. In this way, Zelensky is yet another Jewish mirror of the West’s anxieties and fantasies.