Lessons from Hong Kong’s Fight for Democracy

Interview With a Frontline Activist in Hong Kong

March 26, 2021

Whatever happened to the Hong Kong protest movement that raged and preoccupied global attention for many months in 2019? Ignited by the Hong Kong government’s attempt to ram through an extradition bill in the legislature, the movement evolved in several phases. In the first phase, the struggle against the bill mobilized millions of ordinary Hong Kong residents in mass demonstrations. Soon militant street battles took over and became the most visible face of the movement.

The movement raised 5 demands:

- full withdrawal of the anti-extradition bill;

- withdrawal of the “riot” characterization of protests;

- full amnesty for arrested protestors;

- an independent investigation of police conduct; and

- real universal suffrage.

Despite the Hong Kong government’s withdrawal of the extradition bill, the Hong Kong government did not concede any of the movement’s other demands.

Instead, under pressure from the Chinese state, it launched a furious counter-offensive against the protesters. The movement suffered a series of heavy setbacks: the police siege at Hong Kong Polytechnic University in November exhausted and demoralized many of the most radical protesters; the COVID-19 restrictions on public assembly allowed the police to arrest people at any political gathering; the imposition of the National Security Law in July 2020 further criminalized speech and organizing; and the disqualification of four pan-democratic legislators and the resignation of 15 others in protest left the Hong Kong legislature without any opposition.

Then in early 2021, the government arrested and detained 47 opposition legislators and activists for violating the National Security Law. They now face trial and severe sentences if convicted. Street protests have ceased and frontline activists are now fleeing Hong Kong. Finally, Beijing has begun to overhaul of Hong Kong’s electoral system, increasingly making elections a sham.

What can we learn from the movement? The movement has deeply transformed relationships, radicalized people, and trained a new generation of activists in Hong Kong. The movement’s protest strategy and tactics find reverberations in other protests from Catalonia to Thailand and now Myanmar.

I spoke to an activist who has been a participant in the movement from its early stages and has studied its strategies and tactics. For reasons of security, the activist requested to remain anonymous.

It’s a shame that I was not in Hong Kong and missed the very important mass demonstration on June 12th to stop the Bill from being passed. The first protest I joined was the one on July 16th, and since then I joined most of the protests in the last year.

Back then, I was working with a human rights advocacy organization when the extradition bill was brought to the table. I had been working on building solidarity with mainland Chinese activists who had suffered mass arrests. The bill, which would enable extradition of suspects to mainland, was particularly alarming to me. It did feel like political threats were approaching.

The whole movement was a surprise to me. I thought this would only be concerning for a relatively small group of people. However, at the start of the summer, even before the first mass demonstration took place, people launched hundreds of petitions, made their own leaflets, and organized street booths in every district.

Soon I realized that this was definitely a mass movement. The government’s refusal to withdraw the extradition bill and the police brutality against the protesters triggered a mass and broad mobilization. These protests attracted tens of thousands of ordinary people in Hong Kong many of whom were new to political struggle. People experimented a variety of direct actions and developed massive mutual-aid social networks that transformed and sustained the movement.

The first and most important strategy was to “decentralize” and “distribute” organizing. From the very beginning, the anti-extradition movement rejected having formal leadership. The movement adopted this partly in reaction to the defeat of the last expression of Hong Kong’s democracy movement—the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

Activists wanted to avoid two problems with leadership in that struggle—its lack of accountability and the political repression of its outspoken leaders. So, this time, no one was really identified as a leader or spokesperson of the movement.

People believed that without leading organizations or political stars, they could have more ownership and control of the struggle. When there was a need to evaluate the situation and plan how to retreat safely, the protesters developed their own scout teams and “crowd-scouting” to report back and mark the police location on a live digital map.

When people were injured protesters and couldn’t go to the hospital due to the risk of being arrested, protesters formed networks of voluntary doctors to treat them. When the public transportation was shut down or no longer safe, school bus drivers gave protesters free rides.

When there’re teenage protesters being kicked out by their parents due to involvement in the movement, “adoptive parents” were found to shelter and resources were found to keep them safe and well fed. These are just a few examples of the countless self-organized, crowdsourced and open participatory systems activists created to share information, knowledge and resources with each other.

The “political campaign team” as a good example. It played an important role in distributing information, consolidating direction of the movement, and mobilization. There are Telegram channels which collected and uploaded hundreds of thousands of posters to spread on social media, Lennon Walls, street booths, and pro-movement shops in every district.

It’s worth mentioning that, instead of claiming the credit for the design, all the materials were made anonymously without attribution, and were made available to everyone to download. The crowd-sourcing platforms enabled the responsiveness and flexibility of the campaign.

Let me give you an example that show this network transmitted information with considerable speed. On the night of August 11th, a medic was shot in her eye and blinded. In response, protesters called an action to paralyze the airport the next afternoon. The next morning when I went downstairs to have breakfast, the tunnel in my neighborhood was already covered by posters about the incident. Several middle-aged men were reading and discussing it.

I even passed by a young person standing at the metro and holding a paper board with the slogan “an eye for an eye,” asking people to join the action in the afternoon. When I arrived at the airport hall, thousands of people had already gathered, and some of the protesters were distributing leaflets to inform tourists about the situation.

Protesters were able to react to the incident and organize a response so quickly because no single individual or entity was responsible for designing, printing, posting, or distributing it. Instead, these important roles were fulfilled by different people working together organically. When people find roles which they can play or ways to contribute they are more motivated to participate.

The second key strategy was a commitment to geographical distribution. From the early months of the movement, the protests expanded to various locations throughout Hong Kong, moving from the financial and political centers to peripheral communities. In my opinion, this development is very crucial, because it enabled the protesters to build networks and organizing bases in their own communities.

These bases enabled people to connect the political movement to their daily lives. It also enabled activists to reach more people, helping the movement grow and sustain itself when gathering in the city center became more and more difficult.

The third important strategy was to use militant direct action and peaceful protests and build solidarity between them. Direct action is not new in Hong Kong’s history. Since the mid-2000s, more people have abandoned the idea that Hong Kong people could achieve through political bargaining between the pan-democratic parties and Beijing government, and instead turned to direct action in the street.

In the Umbrella Movement, direction action broke through on the largest scale yet. However, that movement experienced fracturing between groups and marginalization as a result of radical protest tactics. A big division developed between peaceful protests and radical direct action.

By contrast, high levels of police brutality gave justification to radical tactics in this year’s movement. In a survey conducted in last October, over 90 percent of the protesters agreed that the movement can only achieve maximum effect through a combination of peaceful and radical actions. This very high percentage reflects the deep solidarity between all the protesters and a common understanding that solidarity and cooperation between all wings of the movement was necessary.

But protesters didn’t really reach a consensus on what strategies and tactics worked best – street clashes, strikes, elections, or Yellow Economic Circles (YEC) that organized pro-democracy businesses. Nevertheless, the solidarity among protesters enabled them to explore different fronts and build solidarity between them. For instance, when the movement faced challenges in organizing mass demonstration in July 2019, protesters turned to more radical tactics, including breaking into government buildings, shutting down the airport, blocking roads, and strikes.

And in November 2019, when the radical street clashes faced mass arrests and intensifying repression, activists turned to district-level elections, building Yellow Economic Circles, and unionizing as ways to fight back. Using all these tactics and building solidarity between the different networks organizing them helped the movement to sustain itself and made it more difficult to suppress.

This is difficult to answer. Considering how big the movement became and how broad and diverse the participation in it has been, it is really difficult to draw general conclusions about its different ideological trends.

Just like in Taiwan, people in Hong Kong never really broke with the Cold War ideological framework. Ordinary people still associate the left with the Communist Party in China and its agents in Hong Kong.

Since early 2000, there has been more discussions and direct actions critical of capitalism, but anti-capitalism is still not a strong force in Hong Kong society. What’s worse, after the defeat of the Umbrella Movement, left-wing activists were blamed for its failure. In the years since, we’ve seen an emerging wave of right-wing localists who have been promoting an anti-immigrant and local first agenda.

However, in 2019 due to the nature and size of the movement, no individual political group or current could dominate the movement. I would argue that the traditional terminology of left and right is not are useful lenses to look at this year’s struggle.

The diverse and broad participation meant that people went into struggle under the sway of hegemonic ideologies – embracing capitalism, holding confusing and contradictory ideas about communism, and lacking understanding of and empathy with the struggles worldwide. They joined the struggle to protect their democratic rights with whatever ideas they believed.

But the movement has changed people: the participants have become very critical and resistant to the government and police force; the unionizing drives triggered new discussions about labor rights, solidarity and industrial action; the struggle cultivated new solidarity with ethnic minorities; there were many attempts of direct action and mutual aid. There is great potential for the left in these aspects of the movement.

However, some parts of the struggle remained conservative or echoed the ideology of the right-wing localists, such as discrimination against Chinese mainlanders and support for Trump. But most participants didn’t fit into any neat category and held contradictory ideas. So, it was not surprising to find people who are very committed to the democratic movement think they should unionize to paralyze the economy and put pressure on the government, but at the same time accepted anti-immigrant stereotypes about Chinese mainlanders in Hong Kong and think BLM activists are troublemakers.

The street clashes at the frontline escalated from late July 2019 to reach their peak in mid-November. That was a time when there were a variety of street actions every couple of days. The police responded with increasing violence, cracking down on protests and carrying out mass arrests.

In mid-November 2019, the police arrested over a thousand people in a single day during the battles at two universities; many of the frontline protesters were injured and suffered severe, phycological trauma. These violent clashes revealed the limitations of the turn to violent tactics in response to the police.

The improvised petrol bombs protesters used to defend themselves stood no chance against the armed police with their guns, rubber bullets, and water cannons. Once people realized that, they abandoned the radical street action since it was hard to see the possibility that it could win change.

Although there were less confrontational street actions after November, there were still mass street demonstrations at least until the COVID outbreak in January of 2020. These actions were important in the sense that protesters could see each other which keeps keep the momentum going.

On Jan 1st, 2020, more than a million people turned out in one of the largest protests yet. However, the pandemic and police repression made any further demonstrations extremely difficult. The government used the pandemic as an alibi to make all protests illegal and crack down on all street actions with mass and arbitrary arrests.

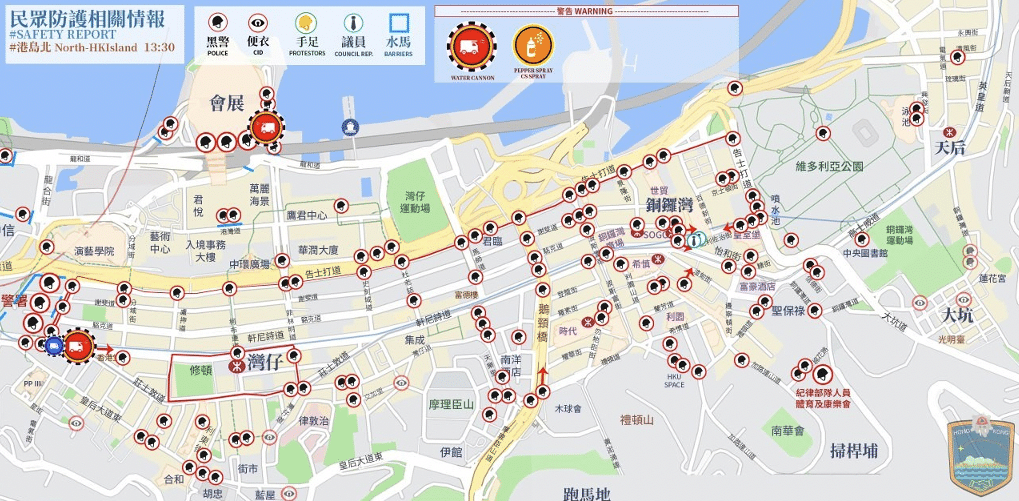

The image below shows how quickly the government deployed police in advance of protests. They infiltrated activist networks, found out their plans, and deployed police at key intersections and streets before protesters arrived, preventing them from assembling in large numbers.

With the decline in street clashes, activists turned to other fronts. They started union drives, Yellow Economic Circles (YEC), and tried to run in elections. These fronts are not new to the movement. Activists had been using them from early stages of the movement, but they grew in importance with decline of mass protests.

It has been a suffocating period of time for people in Hong Kong since the implementation of the National Security Law in July 2020. The government has arrested people for having “secessionist” posters and making “secessionist” statements on social media.

It has issued arrest warrants for activists overseas and disqualified legislators. Shops and restaurants have taken down pro-democracy posters and people have started to delete their social media accounts.

I think it’s worth noting that the National Security Law is more than just a law; it’s a political statement, ideological guideline, and most important of all, it’s an intimidation campaign. The government intended it to make it seem like all sorts of political behavior was a crime, so that people could barely figure out whether or not, and in what way, their actions might violate the law.

This has led people to engage in self-censorship and self-disciplining. The government exploits this to break up solidarity among protesters, especially between front line militants and regular demonstrators. As a result, the militants have become more isolated and even more vulnerable to arrest and repression.

There are practical measures we could take: do risk modelling for yourself and your own network; enhance information and internet security; study cases of political suppression of mainland activists so that we could be more mentally prepared about it. Besides these pretty obvious measures, there are two things we should be doing.

First of all, protesters must strengthen our connections, exchange information, and stay in solidarity with one another. This is essential for us to organize effective and coordinated responses to escalated political repression.

This might sound abstract, but this solidarity grows out of what people in Hong Kong have been doing in the past year. In the street protests, we’ve learned that if there weren’t mass demonstrations backing up the frontline clashes, the police could have easily identified and seized the front liners.

In several strikes, we’ve learned that forming unions and going on strike based on collective decisions better protects workers from facing the repression alone. Most important all, we’ve learned that “they can’t kill us all.”

The crowd-sourcing networks and movement fronts we’ve organized have connected us, built mutual aid networks, and laid the basis for deeper solidarity. This is exactly what we have to strengthen in order to shoulder the risk and survive the government’s counter-offensive against us.

Second, we should learn from struggles in places like mainland China, other Southeast Asia countries, Turkey, and so many other places where activists have faced surveillance, extrajudicial incarceration, and torture. We should learn from their struggles, strategies, and tactics so that we have a better understanding of political repression, how to cope with it, and how to defeat it.

There have been hundreds of protesters who fled to Taiwan in the past year. And it doesn’t seem to be limited to activists. According to a survey conducted in late June right before the introduction of the National Security Law, over 50 percent of Hong Kongers considered emigrating. And 29 percent of those chose Taiwan as their top destination.

But I don’t think it’s a realistic option for the majority of people in Hong Kong. This wave of political refugees is very different from the one after the repression of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

Back then the asylum seekers were a few prominent and outspoken figures. This time, the numbers considering seeking refuge are much larger and many of them were born into families with less privileged backgrounds. So, they don’t can’t afford to leave Hong Kong.

Moreover, most state’s immigration policies favor those “wanted” people with money and “expertise.” It is highly unlikely, especially when they are implementing anti-immigrant policies, that they would accept thousands and thousands of Hong Kong activists in their countries.

Those that do leave have an opportunity to connect with other immigrants and asylum seekers worldwide. I also hope that they will reach out to the local movements in their new countries, and not the politicians. That way the Hong Kong movement and its diaspora worldwide can build solidarity with other struggles and strengthening those and ours in the process.