Out of Lockdown and Back into the Long Depression

Interview With Michael Roberts

July 6, 2021

The pandemic triggered a global recession that shut down whole sections of global capitalism. As the system unevenly emerges from the crisis, Spectre’s Ashley Smith interviews Marxist economist Michael Roberts about the deeper reasons for capitalism’s contemporary malaise, the shape and contradictions of the recovery, and debates between Marxists and Keynesians about the ability of government spending to restore growth and profitability to capitalism.

Michael Roberts is the author of The Long Depression: Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism (Haymarket 2016) and writes regular commentary and analysis on his blog, The Next Recession.

The Covid slump of 2020-21 was basically a supply-side shock due to the global spread of the Covid-19 virus and the failure of governments in the major economies (with a few exceptions) to prevent its spread. There were delayed and bungled measures along with weakened health systems, so economies had to close down as lockdowns and isolation measures were the only answer to avoiding catastrophe. Economically, that meant supply stopped, and then that led to a collapse in demand as people were laid off and businesses crashed.

But recovery is now under way (more or less) in most major economies. Demand was propped up in the major advanced economies through massive government fiscal spending and central bank injections of credit for businesses (particularly large ones). And now through a combination of lockdowns and the incredibly fast development and rollout of effective vaccinations (thanks to publicly funded science), the major economies are now able to recover.

But in the G7 economies this initial recovery has the aspect of a “sugar rush.” The “sugar” of fiscal stimulus and historic levels of easy credit is infusing capitalist businesses and household spending with an energy boost.

Indeed, during the pandemic slump sections of capitalism did not suffer at all; on the contrary, they gained hugely, e.g., the social media and tech sector, the mega-distribution companies, and Big Pharma.

Better-off households also suffered less (at least materially) as they continued to be paid, could work at home, and saved income significantly. This led to a house purchase boom as these sectors of labour looked to change their lifestyles post-Covid.

At the same time, zero interest rates and cheap credit allowed financial institutions to make hay in financial markets and billionaire wealth rocketed as stock and bond markets hit historic highs.

But, for most manual workers in the cities and in low-paid service industries, the pandemic slump was a disaster and with little prospect of returning to “normal” for them in the recovery.

And it’s the advanced capitalist economies and the East Asian states that are recovering best in 2021-22. The so-called global South suffered hugely in the pandemic, with record levels of excess deaths and a massive rise in unemployment and poverty levels. Fiscal support from governments was limited and the rollout of vaccines to get economies going again is way short. Estimates are that the target vaccination levels in these countries will not be achieved until 2023-4!

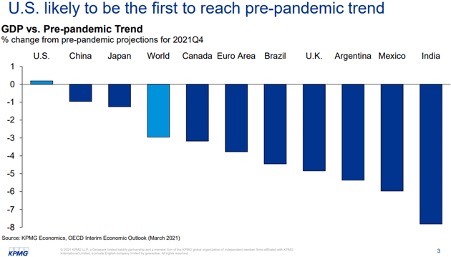

So, what we are going to see is the major capitalist economies of the West and China returning to pre-pandemic levels of national output by the end of this year or in early 2022, but Latin America, Africa, South Asia failing to do so.

Before the pandemic, the world economy was slowing down. Real GDP growth rates in the G7 were dropping to just 1 percent or lower; the so-called emerging economies had growth rates down to 3 percent (hardly enough to cover increases in population). World trade was declining. Even the giant economies of China and India had slowed.

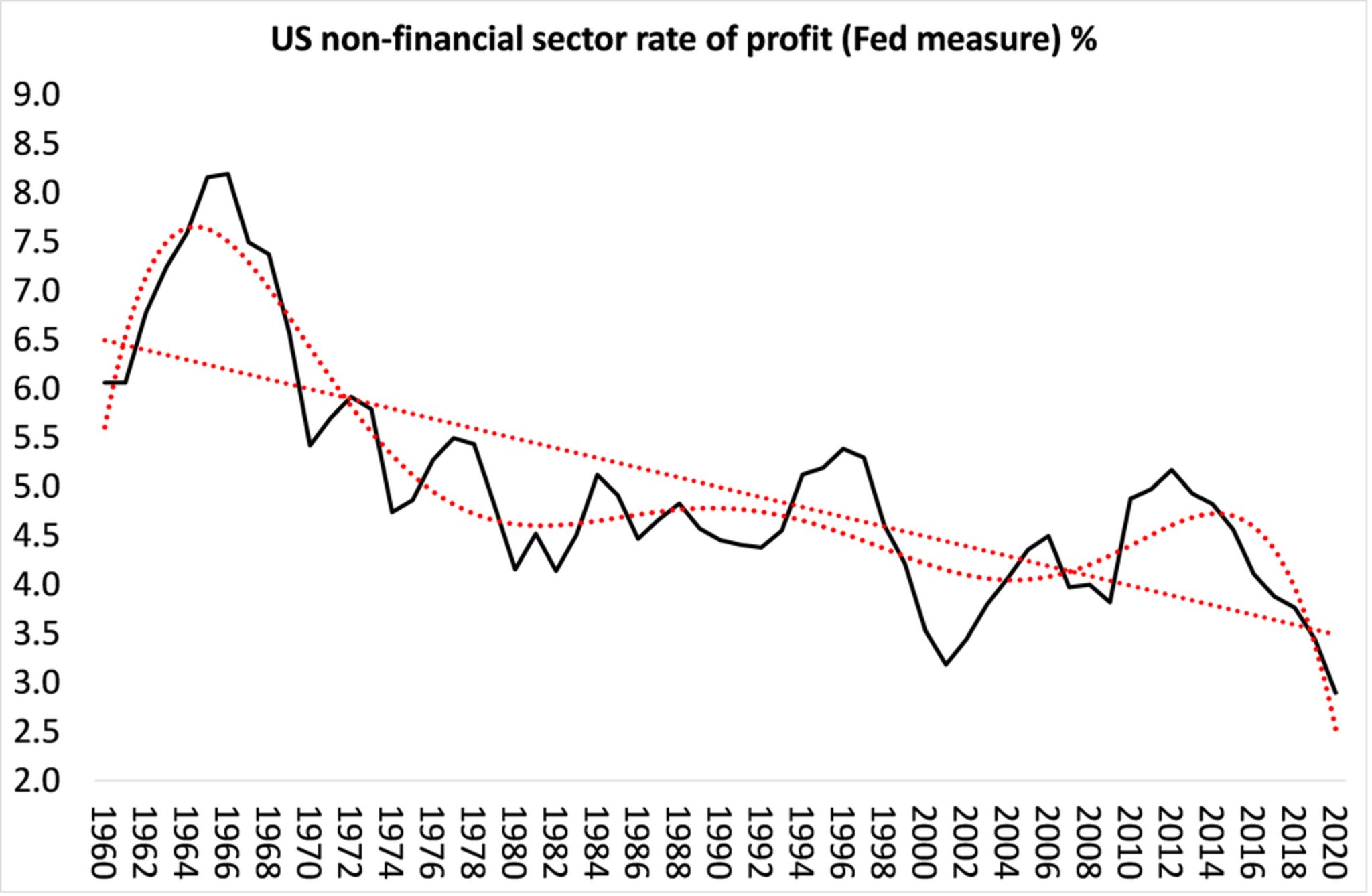

The main reason was that growth in investment in productive assets that can boost the productivity of labor and expand technology and employment had also slowed. In my view, investment and productivity growth are key to developing the productive forces of modern capitalist economies, and they were failing because under capitalism, profitability is the driving force behind investment.

And according to the best estimates, US and global profitability levels are at historic lows. This is the long-term result of the basic contradiction of capitalism: between raising the productivity of labour and sustaining profitability. Over the long term, this cannot be done, and this is the economic Achilles heel of capital.

At first sight, this result seems strange when we read of the huge profits being made by the likes of the so-called FAANGS (the tech and social media monopolies) and Amazon. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule. On average, the profitability of firms in the productive sectors of capitalist economies are low.

That’s partly why profits have been reinvested into financial and other unproductive sectors like property where profitability is higher.

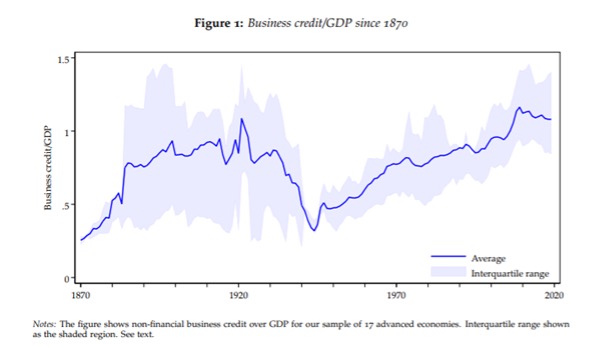

Indeed, it is estimated that before the pandemic, about 15-20 percent of companies in the major economies were what are called “zombies,” i.e., not making enough profit to invest or expand, but just enough to pay wages and service their debts. They are the “living dead” in capitalist terms. At the same time, however, corporate debt is at record highs in most countries, raising the risk of bankruptcies if interest rates were to rise.

All this makes it unlikely that we shall see any significant change post-pandemic from what we saw in the post-great recession decade, i.e., slow growth in investment, low wage growth, poor productivity growth, rising inequality, and unchanged or worsened global poverty.

The pandemic fiscal packages introduced by various G7 governments and, of course, by the Biden administration were emergency measures by states to avoid complete meltdown and catastrophe from the pandemic. In my view, they do not signify a change of ideology or policy by pro-capitalist governments. The usual talk is “let’s get out of this slump and preserve capitalist businesses using state funds and credit and then worry about paying it all down later.” The “later” is still to come.

Biden’s fiscal packages have been heralded as a sea change in government policy and a return to Keynesian macro-management and stimulation of capitalist economies. But first, let’s leave aside the fact that Keynesian stimulus and macro-management was mainly a myth anyway and really the product of a war economy after 1945 which was ditched in the mid-1970s.

Instead let us consider the actual impact of the Biden packages. The latest estimates by Goldman Sachs, hardly a voice of the left, is that after all the machinations of Congress by the end of this year, the Biden package will be equivalent to about 1 percent of US GDP each year for the rest of Biden term. But Biden is going to pay for these partly by increasing taxation by 0.75 percent of GDP a year.

Given that the best estimates of so-called multiplier effects on GDP from fiscal stimulus are about one, that means the net effect of the Biden packages, if fully implemented, might boost US real GDP growth by 0.25 percent a year. The current forecast for long-term us real GDP growth is just 1.8 percent a year. So, the “great” return to Keynes by Biden will be minimal.

If the Biden package will have a limited effect on the US economy, any spillover effect into other economies will be even less substantial. The EU is also planning an economic recovery package that will boost government funds in EU countries with already large debt burdens like Italy and Spain. But again, the impact on the capitalist sectors of these economies will be minimal. Japan is about to announce a fiscal package that aims to “balance the books” over the next decade – hardly stimulus then! Indeed, the latest growth forecast for japan is a further slowing from its pre-pandemic pace of less than 1 percent a year.

And apart from China, Vietnam, and the small East Asian states, the rest of the global South has little prospect of any fiscal stimulus or economic recovery. Most estimates from international agencies are that these economies will not recover to pre-pandemic GDP levels before 2023 and will never recover to pre-pandemic trajectories of economic growth. There is a permanent “scarring” of these weak peripheral capitalist economies.

In the short term, inflation has returned to many economies. This is because of the sugar rush of consumer demand as economies open up again and people start spending down savings built up during the pandemic slump, while companies search for raw materials and components to restart businesses. Coupled with a significant disruption of global value chains, supply cannot meet demand and bottlenecks have created an inflation of prices in raw materials and consumer goods and services.

But is this as transitory as the federal reserve and other central banks claim (though to be fair, there are divergent views within these banks)? Some, like Summers, argue that credit and fiscal stimulation boost demand without engendering enough supply because there is a secular stagnation in investment and productivity in modern economies.

Others argue that credit injections and monetary easing after the great recession did not lead to inflation. On the contrary, easing only boosted financial and property prices. The Keynesian view is that inflation only happens when wage costs rise, i.e., inflation is caused by labor rather than capital. And that is not happening so far.

My view is that price inflation in goods and services in capitalist economies comes about through a combination of demand generated by new value (as expressed in wages and profits) and the pace of money supply growth. But it is the change in value production that matters most.

Capitalist economies have experienced a slowdown in new value growth for decades, so inflation rates have slowed to a trickle. Central banks have tried very hard with monetary easing to get some inflation (2 percent targets, etc.) and failed. Tinkering with interest rates and money quantities cannot deliver even moderate inflation in these conditions.

So, after this initial burst, inflation will rise above pre-pandemic rates (i.e., 2 percent or so) only if the world capitalist economies generate faster growth in new value (unlikely) and/or there are sustained levels of double-digit growth money supply (possible). The latter is what central banks control, and they are divided on how long to maintain that.

The key to answering this is to recognize that capitalists decide whether economies grow or go into slump. By that I mean capitalists will only invest in means of production and employment if there is a profit to be made. Profit calls the tune under capitalism. And as mentioned above, average profitability in the major capitalist economies is low; corporate debt is high, and many firms are just surviving through cheap credit and not investing productively.

But Keynesian theory does not consider capitalist economies from the perspective of profitability. It’s effective demand that decides. If government spending can increase demand, then it can get capitalist economies going. If Marxist theory is a better explanation of capitalist accumulation, then if profitability of capital stays low and does not recover to new higher levels post-pandemic, then government spending will be ineffective.

Economic history has shown that Keynesian stimulus has limited and short-lived effects. As Keynes once said, fiscal spending to levels that actually work would mean the full “socialization of investment” as in a war economy.

If the Marxist economic perspective is correct, then capitalism can only end its long-term stagnation or depression by a significant and sustained rise in average profitability. Historically, that has only been achieved as the result of deep slumps that destroy unproductive sectors and obsolete means of production (either physically as in wars or in value terms through high unemployment and corporate bankruptcies).

This would lay the base for a sharp rise in the profitability of those capitalist sectors that survive the slump – what Schumpeter called a process of “creative destruction.” Is that likely? For the moment it seems not, as the zombie companies are being propped up rather than liquidated.

It’s true that the replacement of sectors of labor by robots and AI, and the reorganization of work to reduce costs could provide the ground for new investment and productivity growth. But it is likely to require another major slump before the end of the 2020s to deliver the prospect of increased profitability and the conditions to impose these changes on behalf of capital. Otherwise, it’s another leg in the long depression as we saw in the 2010s.

In the short term, socialists should be demanding that any return to work should not mean lower wages and worse conditions. And yet that is what many sectors face. Indeed, in the US there are still nearly 8 million workers who were employed before the pandemic without jobs.

Also, what the pandemic has proved beyond all doubt is that the privatized and hollowed out health systems in the major capitalist economies were totally inadequate to the task. Health systems have been starved of funds, privatized, and neglected.

That also applies to other key public services like education, transport, communications, etc. Working class militants should be demanding a properly funded state-run health service free at the point of use. This would have wide popular support.

Longer term, socialists should be arguing that there should be no return to normal. Post-pandemic, that should mean massive public investment in social needs, an end to growing inequality of wealth and incomes, and a proper plan internationally to cope with the impending disaster of global warming, climate change, and environmental destruction that capitalism has engendered and cannot solve. And don’t forget there will be more pandemics unless fossil fuel and mining, industrial farming and uncontrolled viral research are stopped.

All this means, of course, a complete change in economic and social organization from production for the profit of a few multinationals to production by public companies under democratic control for social need globally. That’s where political struggle takes over from economic analysis.