Introduction

Jack Norton and David Stein’s wide-ranging criticism of our Catalyst essay provides a welcome opportunity to further an important debate on the origins of American mass incarceration.1John Clegg and Adaner Usmani, “The Economic Origins of Mass Incarceration” Catalyst, 3 (3) Fall 2019: 9-53. Jack Norton and David Stein, “Materializing Race: On Capitalism And Mass Incarceration” Spectre October 22, 2020. As we argued in our essay, we think that many scholars and activists have mistakenly absorbed large parts of the standard story of the punitive turn, and as a result have misunderstood many of its key features. And so we are glad to be part of an exchange that we hope can clarify how mass incarceration was built and thus how it might be ended.

Yet precisely because Norton and Stein’s reply to us ranges widely, writing our reply has been a tricky exercise. It is not always clear to us how they disagree. (Further, since their criticisms often extend beyond the scope of our co-authored work they sometimes touch on issues where we ourselves disagree). At times Norton and Stein appear to concur with us that the modern American carceral state was the result of the toxic mix of a rise in concentrated disadvantage at mid-century, a resulting increase in violent crime, popular pressure to do something about that increase, and (above all) structural, longstanding impediments to redistributive remedies. At other times they appear to take umbrage at these same arguments.

In what follows we therefore first reconstruct what we take to be their two strongest arguments — that we mischaracterize the existing literature on mass incarceration, and that we misunderstand the role played by racism in its origins. In neither case do we accept their criticism, but while we doubt that addressing their criticisms at length will resolve our dispute, we are confident that it will clarify the terms of our disagreement. This exercise has been useful for us, and we hope it will be similarly useful for those who are reading this exchange.

A Word on Crime Data

Before we address these two main criticisms, however, we think it would be helpful to say something about our use of crime data. Many of Norton and Stein’s concerns about the evidence we present are reasonable. Crime statistics are notoriously unreliable, as they suggest, both because of the inconsistent and biased ways in which they are collected, and because the underlying definitions of crime vary across place and time. Moreover, given the way that discussions of crime have been overwhelmed by racist stereotypes of black criminality and conservative pieties about “personal responsibility,” it is unsurprising that some have come to see these statistics as a cursed talisman, wielded only by racists and apologists for mass incarceration. We agree that it is important to be aware of these problems and this history.

Yet it is a much stronger claim to argue that these data can teach us nothing. Though they are imperfect and fraught, there are various things that researchers can do to guard against drawing unwarranted conclusions. In our piece we focus on trends in violent crime and especially homicide. These are much less subject to concerns about reporting bias, especially in recent decades. Criminologists have thought hard about these biases, and so it bears emphasizing that we are aware of none who would argue that one or more of the three key features of American violence we describe in our article — the exceptional levels of homicide in the US relative to comparable countries, the rise in crime between the 1960s and the 1990s, or the racial disparities in crime victimization and offending — are artifacts of statistical inconsistencies. This is not to claim that these data estimate these differences with precision. But, as in the case of using educational attainment as a proxy for class (which is currently the only way to draw any inferences about long-run trends in class disparities in American incarceration rates), we must do the best we can with the imperfect data at our disposal.

It is important to emphasize that this is not a challenge that is unique to quantitative, “bourgeois” research, as Norton and Stein imply. The scholarship that Norton and Stein cite, for instance, is also forced to make contestable decisions about measurement (e.g. measuring racist intent by the use of racially-coded words by politicians) and sampling (e.g. inferring the motivations of all elites from statements made by particular elites, telling general stories about the punitive turn from case studies in a particular place and time, and taking samples of prominent bills to tell a legislative history). The point is not that these strategies teach us nothing, but that social science (whether qualitative or quantitative, bourgeois or radical) is difficult.

However, one of the consequences of the deep-seated skepticism of crime data is that many accounts of the origins of mass incarceration commit the error of ignoring crime altogether. This has unfortunate political consequences, especially on the left. This is both because a failure to address the reality of crime will weaken efforts to resist the carceral state, and because crime is itself a symptom of oppression whose costs are borne by the most oppressed members of society.2These political costs of overlooking crime are compounded in communities with high rates of victimization, since the latter can itself undermine the social solidarity necessary to fight mass incarceration. An African American man today is about 8.4 times more likely to be murdered than a white man (excluding police killings, this ratio is around 8.7).3Lisa Miller calls this “racialized state failure” (Miller, Lisa L. “What’s Violence Got to Do with It? Inequality, Punishment and State Failure in US Politics.” Punishment and Society 17, no. 2 (2015): 184–210.) See http://bit.ly/nortonstein_replication for calculations. Those who are attuned to the struggles of the oppressed should not turn a blind eye to such an acute, and acutely racialized, dimension of oppression. Nor, we think, should those on the left be surprised that America’s grotesque levels of concentrated disadvantage breed grotesque levels of violence.4An American is about 3.8 times more likely to be a victim of homicide than a European.

Of course, such insights have been a mainstay of many left-wing analyses of crime and punishment, from anarchist and black power prison writings, to abolitionist and “left realist” approaches to critical criminology.5For instance, Policing the Crisis, a work that Norton and Stein favorably cite, explores a period of racialized public anxiety about crime in Britain that has both similarities and important differences to the period preceding mass incarceration in the US. Yet although Stuart Hall and his co-authors do criticize a media-driven “moral panic” about mugging, one that involved both racism and misuse of crime statistics, they don’t deny that violent crime was on the rise (albeit much less than in the US at the same moment), nor that there were stark racial disparities in offending, both of which they (like us) attribute to relative economic deprivation. They further underline that crime is a “real, objective problem for working people trying to lead a normal and respectable life” (p. 149) and that popular anxieties about crime were not “the product of a conspiracy on the part of the ruling classes and their allies in the media” (p. 176). We have been inspired by these traditions to think and write frankly about this subject. Yet writing frankly means more than simply taking heed of violence. It means considering the possibility that America’s outlying levels of violence have something to do with its outlying levels of punishment. In their piece, Norton and Stein liken the harms of violent crime to the harms of asthma. This analogy is telling, for while asthma does cause harm, it has (to our knowledge) no causal relevance to important developments in American politics. But one of our main arguments is that the real and dramatic rise in violent crime in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s — which was a symptom of the abandonment of the poorest sections of American society — was a necessary but insufficient condition of the punitive turn. In our view, downplaying the effects of crime and violence, as Norton and Stein do and as many others have done before them, leads to bad analysis. And a bad analysis of mass incarceration threatens to undermine our efforts to dismantle it.

Our Characterization of the Literature

Norton and Stein’s first charge is that we mischaracterize the literature on mass incarceration in general, and that we ignore our debts to Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag in particular. We think they are right that Gilmore and other radical scholars have made some of the points that we do. But, on the one hand, they overstate the influence of this radical scholarship on the literature (and the public discussion) of American mass incarceration, which is indisputably framed by Michelle Alexander’s arguments in The New Jim Crow. That is why we focused on those arguments in our piece. And, on the other, they overstate the overlap between our account and the radical scholarship to which they adhere. The radical literature, like The New Jim Crow, has tended to ignore or downplay the contribution of crime, particularly violent crime, to the punitive turn of the 1970s and 80s. In our essay we argued that violent offending rose to exceptional levels during this period (due largely to the deterioration of social and economic conditions in American cities), that the American public noticed this, that American politicians had to respond to the resulting public anxiety, and that they opted for a punitive response because punishment is less expensive (and thus requires less redistribution of wealth) than social policy. None of these arguments are to be found in either the standard story or the radical scholarship Norton and Stein cite, but they are central to our account of where mass incarceration came from. This is why we wrote our piece.

The Standard Story

In the standard story of mass incarceration, the punitive turn was the handiwork of a cadre of white Republican politicians who used a racially-coded “law-and-order” agenda to win the South away from the Democratic Party. The result was the War on Drugs, which criminalized drug use in black communities but ignored it in white ones. It is these kinds of prisoners, the argument suggests, who fill American prisons.

As we have argued in more detail elsewhere, this argument has observable implications for public opinion, voting patterns, and the effects of black enfranchisement for which there is very little evidence. In our article in Catalyst we simply noted three kinds of weaknesses in this argument:

- It cannot explain why the white incarceration rate also skyrocketed over the last 30 years, why, as a result, racial disparities in incarceration are lower today than they were in 1970, or why a white high-school dropout is 15 times more likely to be in prison than a black college-graduate. None of this makes sense if, as the standard story maintains, mass incarceration targeted black people accused of offenses largely ignored in white communities.

- It obscures the fact that rates of violent offending (however one defines it) rose precipitously between 1960 and the mid-1990s, and that violent offenders make up a much larger share of the American prison population than those in prison for drug offenses.

- It fails to recognize that American mass incarceration has not been the handiwork of individual actors at the federal level, but rather tens of thousands of officials at the local and state level, most of whom are, exceptionally in America, subject to the influence of the electorate.

Norton and Stein charge that this standard story is a “caricature” of existing scholarship. By this they mean that there is a long tradition of radical and Marxist scholarship that has theorized the “class character” of the penal state, and also that scholars of American incarceration specifically have noted that its victims are both black and poor (the “intersection” of race and class). In support of this, they quote Aviva Chomsky, who writes that “virtually all studies of the carceral state see the intersections of race and class as central to its nature.” They later cite Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who argues explicitly against the view that mass incarceration is “something that only Black people experience.” The result, they suggest, is that we are battling a strawman and “intentionally or not … dissuad[ing] potential readers from engaging the actual scholarship on the topic.”

In our essay we argued that violent offending rose to exceptional levels during this period (due largely to the deterioration of social and economic conditions in American cities), that the American public noticed this, that American politicians had to respond to the resulting public anxiety, and that they opted for a punitive response because punishment is less expensive (and thus requires less redistribution of wealth) than social policy. None of these arguments are to be found in either the standard story or the radical scholarship Norton and Stein cite, but they are central to our account of where mass incarceration came from. This is why we wrote our piece.

Norton and Stein are right to say there is a tradition of radical and Marxist criminology that has warned against the temptation to think that mass incarceration is simply race-based. They are also right that we say regrettably little about any of this scholarship in our essay. But they are wrong to think this means that we are battling a strawman.

First, while Marxists in general, and Gilmore in particular, have written insightfully about the carceral state, their views are far from standard. We do not focus on the left-wing scholarship that Norton and Stein favor because what we call “the standard story” is not really the left’s story, but the liberal story — notably The New Jim Crow story. And this liberal story has been much more influential than the left-wing one.6We would add that it has also been influential on the left, as one can see from the other criticism of our article published by Spectre (1, no. 2), by Peter Ikeler and CalvinJohn Smiley, which is largely a defense of The New Jim Crow. Because there are few overlaps with Norton and Stein, we will address those criticisms in a separate response.

As we say in our essay, Alexander’s The New Jim Crow is the single most cited piece of scholarship in the literature on mass incarceration. It has been cited more than 12,000 times since its publication in 2010. Gilmore’s Golden Gulag, which is probably the most influential statement of a Marxist explanation of the American carceral state, has been cited roughly 3000 times since 2007. Put another way, by this metric and adjusted for date of publication, Alexander’s book is roughly 5 times more influential than Gilmore’s. Note that Gilmore, in the very interview that Norton and Stein cite, complains that “mass incarceration has, unfortunately …come to stand in for ‘this is the terrible thing that happened to Black people in the United States’.” She is, in other words, complaining about the hegemony of the standard story.

Golden Gulag

Yet even if they are wrong to accuse us of battling a strawman, Norton and Stein could of course still complain that we are treading ground already well-trodden by previous left-wing critics. Why not simply tip our hats to writers like Gilmore, and the parade of scholarship cited in Norton and Stein, who have been battling the phantoms of the standard story for a long time?

It is a fair question. There is much to learn from Gilmore’s work, in particular. We regret not recommending it more highly in our piece. While Golden Gulag is primarily an explanation of California’s prison building program, there are many overlaps with our broader account of the origins of mass incarceration. Both, for instance, identify deteriorating labor markets and the emergence of the austerity state in the 1970s as key underlying conditions. As we clarify below, we are sympathetic to Gilmore’s argument about the rise of a “surplus population” abandoned not just by capitalist industry but also by federal and state support, a loss for which local and city governments were unable to compensate due to what Gilmore aptly calls “fiscal apartheid.” For us it was precisely these conditions that channeled real concerns about the rising incidence of crime and violence (itself largely driven by such “organized abandonment”) into the austerity program of mass incarceration.

Further, while we will have more to say about racism below, we endorse much of Gilmore’s account of its role in the rise of mass incarceration. Gilmore convincingly argues that racism not only shaped California’s “law and order” politics but was also exacerbated by the crisis and restructuring itself.7On the relationship between austerity and racism Gilmore writes that “Racist and nationalist confrontations heightened, driven by the widely held—if incorrect—perception that the state’s public and private resources were too scarce to support the growing population.” She also cites the “layoffs of thousands of aerospace engineers” in 1970s California as “an important foundation for invigorating active consciousness of a normative racial state”, suggesting that these layoffs might help to explain the popularity of “law and order” politics (p. 40). And we also agree with her criticism of what might be called the “race reductionist” interpretation of mass incarceration: including the idea that modern prisons represent a continuation of slavery,8In Gilmore’s view this is “a product of mixing the Thirteenth Amendment with thin evidence”, as well as overemphasizing the role of private prisons in the prison boom. and that white prisoners can be considered “collateral damage” of a system designed to “to get rid of people of color.”9In questioning David Roediger and Pem Buck’s notion of white prisoners as collateral damage (a “reserve army of whiteness”) Gilmore appears to defend the idea of a “convict race” — that black and white prisoners, who share the same fundamental interests, are pitted against each other by prison managers to more effectively control them.

Given all this, why do we not lean on Golden Gulag more heavily?

The key reason is that Gilmore denies the chief mechanism that links deteriorating labor markets to rising incarceration: namely, the rising crime rate. Gilmore’s vivid summary of the narrative in Golden Gulag — “crime went up, crime went down, we cracked down” — suggests as much. In her view, the prison boom had no relation to crime.

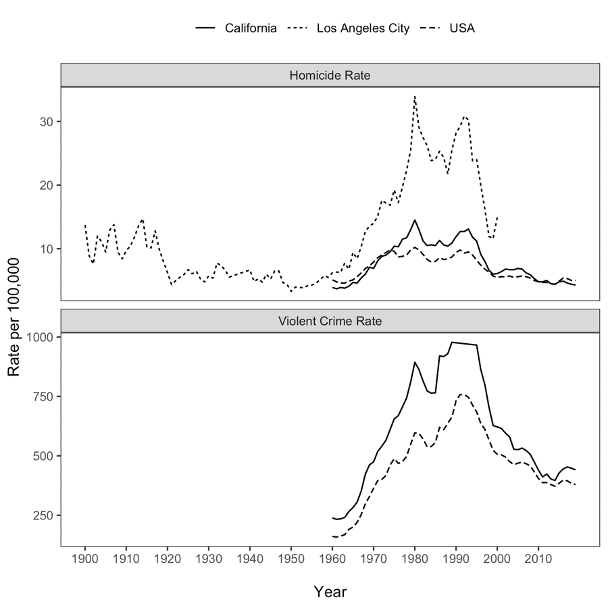

Yet the available data paint a very different picture. In fact, violent crime in California rose steadily from 1960 to 1980. In her book, Gilmore makes a lot of the fact that the rate of violent offending fell slightly in the early 1980s, just when California started building more prisons. But, as Figure 1 shows, this amounted to just a three-year fall of 14% from a local peak in 1980, following an uninterrupted rise of 270% over the previous 20 years. Moreover, the rate of violent offending once again rose from 1984 to 1993.10It is possible, as Gilmore suggests, that some of this later observed increase in offending was driven by the “crack down” itself, due to a negative impact of mass incarceration on economic prospects and social cohesion in the most impacted neighborhoods. But this theory is not particularly consistent with the fact that crime rates plummeted from the mid-1990s even as prison populations continued to rapidly increase. During the three years when “crime went down,” there were more homicides in California than in the entire decade of the 1960s. As Figure 1 shows, Gilmore’s sequence is true neither of California nor of the nation as a whole.

In our view, it is no surprise that politicians were able to exploit people’s fear of crime in order to pass prison-building and punitive legislation. Note that this was true not only of white and racist politicians. In fact, there is evidence that black elected officials in particular faced pressure in high crime cities like LA to do something about unprecedented levels of violence.13Mike Davis, City of Quartz (Verso 1990), pp. 272-292, and Donna Murch, “Crack in Los Angeles: Crisis, Militarization, and Black Response to the Late Twentieth-Century War on Drugs.” The Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (2015): 162–73. Both Davis and Murch see that pressure as stemming particularly from “middle class” or “elite” African Americans in LA. See below for our own findings with respect to this interpretation. We will return to this point below.

It should be noted that in other work Gilmore has been more willing to discuss the reality of crime and violence, including among the victims of organized abandonment.14See, e.g., Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Race, Prisons, and War: Scenes from the History of U.S. Violence,” Socialist Register (2009). Gilmore’s new book, Change Everything: Racial Capitalism and the Case for Abolition (forthcoming 2022) also promises to treat explicitly the problem of “interpersonal violence.” Her frankness in this respect is consistent with a left-wing tradition of crime writing that is generally unabashed in confronting the problem of violence in poor and working class communities, a tradition in which we would situate our own claim that “crime is an index of oppression.” It is predominantly the liberal, not the left-wing, critics of mass incarceration that have come (in recent years) to obscure that oppression by denying or underplaying its harmful consequences, thereby reproducing what Jackie Wang has called “the politics of innocence.”15Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism, Semiotext(e), 2018.

Gilmore is rightly critical of much of the liberal narrative, yet insofar as Golden Gulag also elides the fact that violent crime was rising sharply prior to the prison boom, it reproduces the standard story in this key respect. Each of the main puzzles about American punishment (why America incarcerates more than comparable countries, why the rate of incarceration rose, why poor and black people are more likely to be in prison) can also be posed about American violence (why America is more violent than comparable countries, why the rate of violence rose, why are poor and black people more likely to be victims and perpetrators of violence). The principal objective of our essay was to show what an account of mass incarceration that took American violence seriously might look like. Gilmore’s book, while very insightful in many other respects, does not do this.

The book also has a key theoretical weakness. In summarizing her argument, Gilmore sometimes explains the punitive turn by its effects. She argues that the purpose of the prison building program was to absorb the four kinds of “surpluses” created by the economic crisis of the 1970s: surpluses of land, capital, labor, and state capacity. She calls this, provocatively and famously, “the prison fix.” The origins of mass incarceration lie in the fact that it solved the problems that capitalism created.

This is a functionalist argument, by which we mean it is an argument in which the real or intended effects of an institution are adduced to explain its causes. Functionalist arguments can be powerful, but they require mechanisms linking observed effects to causes (whether selectional, as in evolutionary biology, or intentional, as in when one explains the drinking of water by the quenching of thirst). Yet Golden Gulag is extremely thin on the links between capitalist crisis and California’s punitive turn. Gilmore never explains what would have happened had prisons not solved the crisis (which could furnish a selectional explanation, if it could explain why prisons were the necessary consequence of any capitalist crisis that remained unresolved). And while she refers repeatedly to a “power bloc” pulling the strings of the punitive turn, it is never clear just who is involved and what they knew about the functional imperatives they were serving (which could furnish an intentional explanation). It makes sense to argue that prisons are somehow functional for capitalism, but there is something strange about using this argument to explain mass incarceration. After all, capitalist crises are ubiquitous, but mass incarceration is unique. For most of capitalism’s history, the modal response of elites to economic crisis has been to abandon the poor, not to incarcerate them en masse.

Gilmore is rightly critical of much of the liberal narrative, yet insofar as Golden Gulag also elides the fact that violent crime was rising sharply prior to the prison boom, it reproduces the standard story in this key respect.

The more straightforward, empirical problem with this formulation is that it seems to require that California’s prisons could have absorbed the surpluses that capitalism produced. But the prison system was simply not economically significant enough to perform this function, in any of the four domains Gilmore identifies. Of all the arable land idled in California since the 1980s, prisons were built on no more than 1.5%. Of all the capital available for investment, expenditures on prison construction never absorbed more than 0.5%. Of all the people left unemployed by capitalism in California in the 1980s and 1990s, only about 6% of them at any given time were in prisons or jails. And of all the state capacity that the government of California retained, only a small proportion was absorbed in punitive ends: 4% of California public employees are correctional officers, 5.7% are police officers; and only around 7% of California’s total (state and local) budget is spent on prisons, jails, or the police. (This underscores a point we emphasize but which is missing from almost all the left-wing scholarship on mass incarceration: prisons are an exceedingly cheap response to social disorder). In other words, in any given domain, anywhere from 93-99% of the surpluses Gilmore identifies were not absorbed by prisons. Prisons managed the capitalist crisis, but they in no sense fixed it.16For calculations and sources, see http://bit.ly/nortonstein_replication. At times Gilmore appears to acknowledge that “the prison fix” was a failure, but her argument implies that it would have been reasonable for a significant group of actors (presumably economic or political elites) to imagine that it could ever have succeeded. That is hard to credit in light of these numbers.

In short, while we agree with Norton and Stein that there is a lot to learn from Gilmore’s work, the basic architecture of her argument is different from ours. We emphasize the necessary (although insufficient) role of crime and violence, which she denies. And while we agree that the origins of mass incarceration lie in the exceptional depredations of American capitalism, our account of the link is different.

Norton and Stein

Like Gilmore, Norton and Stein mostly evade the question of violence in their response to our essay. They acknowledge that “the homicide rate spiked after 1960,” and they argue that high levels of violence are harmful. But they do not give these facts any weight in their explanation of the punitive turn. This is due to their fealty to the key arguments of the standard story. Here Norton and Stein diverge substantively from Gilmore. While Gilmore rejects the claim that a media-driven “moral panic” about crime led to the politics of “law and order,” Norton and Stein defend that view. Moreover, they seem to concur with Michelle Alexander that this moral panic was largely a reaction to the gains of the civil rights movement, a bait-and-switch engineered by clever political entrepreneurs. By contrast, we argue that the dramatic increase in crime and violence influenced American public opinion directly, and that this furnishes a necessary (but not sufficient) explanation of the change in public policy at the state and local levels.

Why believe our account rather than theirs? First, note that the fact that some politicians (or even the public) conflated opposition to the civil rights movement with fear of crime does not establish that the public worried about crime because they worried about civil rights. In fact, as Michael Flamm argues, it may be that a racist white public could be convinced to express their fear of black civil rights in the language of crime because they were already worrying about crime.17Michael Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s, Columbia University Press 2005.

Even setting this point aside, there are two obvious problems with the view that the change in public opinion was driven by the civil rights movement. First, as our data show, both white and black public opinion trended together. If public attitudes towards punishment were driven by racial anxiety, why did black public opinion turn so punitive, so dramatically? In the late 1980s and early 1990s, when cross-sections of nationally representative black Americans were asked by the General Social Survey whether courts were too harsh on criminals, about right, or not harsh enough, around 80% of black Americans consistently said they were not harsh enough; only 10% said they were too harsh. (And nor can this punitiveness be attributed to middle-class male spokespeople, as Norton and Stein suggest. Over this period, these same polls show that, if there were class differences, they ran in the other direction: poorer African Americans were more punitive than the rich). Second, public punitiveness peaked in the early 1990s, when crime and violence did, whereas punitiveness was in fact still at historically low levels in the mid-1960s, when the civil rights movement was at its peak.

Yet Norton and Stein not only reproduce the standard argument that rising concern about crime was driven by fear of civil rights, they also assert that politicians routinely ignore public opinion, so any attitudinal changes were anyway causally unimportant. They are of course right that there are many domains of public policy where public opinion is mostly irrelevant. But there are two reasons that criminal justice is not one of them, especially in the United States. First, the US has a more democratic criminal justice system than most countries. It may be unique in the extent to which officials at all levels of the criminal justice system are subject to popular influence. Second, unlike other areas of public policy (healthcare, welfare, education), criminal justice policy does not threaten elite interests. Because punitive responses are hyper-targeted, they are inexpensive. And because they are inexpensive, they do not require anything much of elites (prisons, police, and the courts consume only about 1.4% of US GDP). Because penal policy requires little by way of redistribution from the wealthy to the poor, it is an area of public policy in which political and economic elites can afford to be more responsive to public opinion. Indeed, we argue that punitiveness is the way in which a regime of permanent austerity responds to public clamor for protection.

Norton and Stein dispute the idea that public opinion could have mattered not only by arguing that public opinion is routinely ignored in American politics, but also by pointing out that the public (especially the black public) had many progressive ideas about what ought to be done about crime (“all-of-the-above strategies”). But here they seem to have misunderstood our argument. We agree that public opinion does not alone make policy. Our argument was that the change in public opinion furnished the impetus or pretext for federal and especially state and local officials to respond. District attorneys, judges, state legislators, city councilors, mayors and sheriffs could not ignore rising public concern about crime; those that did lost elections.

Yet we did not argue that this fact determined the form of this response. As we emphasize throughout our article, the form of this response is explained by the exceptional features of American political economy. Social remedies are expensive and punitive remedies are cheap. Because the underdevelopment of the American labor movement has insulated the rich from taxation and redistribution, penal policy was the American political system’s modal solution to public clamor about crime.

In summary, the standard story is not a strawman, but the position which has the greatest influence in public and academic discussion of American mass incarceration. While left-wing alternatives (like Gilmore’s, or the related account sketched in Norton and Stein) correct the class-blindness of the standard story, they tend to reproduce two of its errors: they overlook the key role played by the rise in crime, and they have little to say about the exceptional influence of public opinion on American criminal justice policy.

The Role of Racism

Norton and Stein’s second major charge is that we mistheorize racism and its relationship to class and capitalism, and that we give it short shrift in our account of mass incarceration. They claim that we “both dismiss the role of racism and naturalize it,” by which they appear to mean that we relegate racism to a mere background condition, rather than making it a central actor in our narrative. They are also unconvinced that one can analytically parse racism from other causal factors—they call the distinction between race and class a “fictive separation”—and suggest that we fail to “take racism seriously as an integral feature of capitalism.” Finally, and most damningly, they accuse us of “apologizing for racism” in describing conditions which make support for caste-based exclusions “rational” for certain groups of workers (if only in the short run).

In these respects Norton and Stein mostly misread us. On none of these points do we find their reply convincing. But their misreading is in some sense understandable. These are thorny issues, and our article did not (1) provide a definition of racism, (2) clarify how we think racism does and does not explain mass incarceration, or (3) give an account of its relation to capitalism.

We are thus grateful for the opportunity to clarify each of these points in our response. Below, we explain that the real disagreement here is not the methodological one that Norton and Stein imply (both conceptual distinctions between class and race and counterfactuals are unavoidable in arguments about the causal importance of race), but substantive and empirical. Racism can explain racial inequality in a variety of ways, and Norton and Stein are in fact simply disputing our particular explanation of how racism primarily matters. We further note that Norton and Stein’s ruminations on this point lead them to a kind of idealism that reifies race and racism. They thus end up telling a story about mass incarceration that centers on the racist ideas in white people’s heads, rather than on the balance of social forces. Again, our objections to such claims are fundamentally empirical, but we also raise questions about their political implications.

What Is Racism?

Racism can be defined as an attitude, an ideology, and a set of social practices. The term colloquially refers to a prejudice or animus directed towards people perceived to belong to an inferior “race.”18“Racism is the dogma that one ethnic group is condemned by nature to congenital inferiority and another group is destined to congenital superiority.” Ruth Benedict, Race and Racism (Routledge, 1942), p 97. “Race” in this definition suggests something innate and unchangeable, but it should be noted that culturalist versions of racism allow for more variation. The ideology can be more specifically defined, following Barbara and Karen Fields, as a system of beliefs that supports a social or legal double standard based on perceived ancestry.19Barbara and Karen Fields, Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life (Verso 2012). More simply, for William Julius Wilson racism is “an ideology of racial domination” (The Bridge over the Racial Divide (Berkeley 1999), p. 14). These double standards can in turn be seen as a broader social or institutional practice of “racism” or “racial domination.” Such beliefs and practices, particularly (though not exclusively) in the West, have tended to give rise to an inconsistent and unscientific notion of “racial difference.” In this sense racism produces “race.”

Sometimes, “racism” is used differently to mean persistent racial inequality, as in now-commonplace references to “structural” or “systemic racism.” Yet here the danger is that we confuse description for explanation. Any given explanation of racial inequality must distinguish between two main causes of that inequality. First, present-day racial inequality might be explained by present-day racism, in the limited sense of one or another kind of discrimination by actors or institutions. Second, present-day racial inequality might be explained by inherited racial inequality (or alternatively, past racism).20See Gilmore 2002, p. 268, FN 7, which offers these two explanations for racial inequalities in home ownership Black Americans (on average) might have worse outcomes than white Americans in part because they (on average) inherit fewer private and public resources (i.e. a worse position in the overall resource distribution), which means that they will (on average) do less well in schools, labor markets, the search for housing, etc.

Norton and Stein end up telling a story about mass incarceration that centers on the racist ideas in white people's heads, rather than on the balance of social forces.

The first of these paths can be called the direct effect of race and the second the indirect effect, in which race (or the legacy of racism) is mediated by class.21Following Fields, one might prefer to call these as the effects of racism, since using the term “race” to denote a fixed cause in the world would seem to reify it. But one advantage of the language of social scientists is that not all race-based inequality is necessarily the result of racism. For instance, in the United States, the indirect effect of race ultimately has its origins in the fact that black Americans were enslaved. Barbara Fields has argued that black enslavement was not a result of settler racism but rather the result of the relative powerlessness of black Africans viz-a-viz Native Americans and indentured whites (Fields, “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America”, New Left Review I/181 1990). In this account racism was the effect of enslavement, but not its cause. If this is right, it would not be correct to describe the “indirect effect” as the effect of “past racism” alone.

Norton and Stein argue that our error is to analytically distinguish class from race. But since even they use separate terms instead of a single concept (e.g. “classrace”), by this they cannot mean that we are wrong to think “class” and “race” are distinct concepts. Our disagreement is not methodological, as they suggest, but in fact substantive. What they mean, we think, is that our account elevates the mediating effect of class (the “indirect” effect, or past racism) and minimizes the weight of present day racism (the direct path).

In extremis, Norton and Stein are accusing us of class reductionism. This is the view that all racial disparities are but class disparities in disguise (in these terms, that only the indirect pathway is in effect). It is quite straightforward to show that this class reductionist position is wrong. Black people and white people from equivalent class backgrounds do not have equivalent prospects in the United States, in a variety of dimensions. For instance, Figure 2 in our original article shows that there are sizable intra-class racial disparities in incarceration rates.22Though here, because better data are not available for the 1940-2020 period, we were limited to using educational attainment as a proxy for class. In general, the relative size of the direct and indirect paths will depend on how one defines class. This is yet another reason that one cannot avoid conceptual distinctions between them. Nothing in our piece was defending this view.

But, importantly, to have shown that this class reductionist position is wrong is not to have proven that the direct path matters just as much as the indirect one. The indirect and direct effects are quantities, and so the observation that they are both important simply invites the question: how important, relative to each other? Norton and Stein seem to think we are opening a debate on whether race matters. But this was not our point. The question to be answered is not whether it matters, but how.

Consider, for example, the popularity of the direct path as an explanation for racial disparities in incarceration rates. Most critical scholars imply that some combination of racist law-making, policing, prosecuting, judging, and sentencing is responsible for the disproportionate share of black people in America’s prisons. And of course this kind of discrimination exists and must be fought. But Norton and Stein skip over the evidence (which we cite in the original article) that racial disparities in the criminal justice system are mostly the result of inequality in circumstances outside the criminal justice system, rather than racial inequality in treatment by actors and institutions that comprise it. This evidence suggests that a world without racist lawmakers, police, prosecutors, judges, and parole boards would still be a world in which a highly disproportionate share of black Americans languished in prisons. We will have more to say about the political consequences of this later.

Racism and Mass Incarceration

A related question is how to think about the role of the racial prejudice of politicians and the public in the origins of mass incarceration. As we have already noted, both in the standard story and Norton and Stein’s version of it, this kind of racism is causally decisive.

To see how our argument is different, it may be helpful to first reprise our view. Our argument in the Catalyst essay was that mass incarceration should be seen as the bitter fruit of American slavery.23We are now at work on a book, entitled From Plantation to Prison, which makes this argument in more detail, drawing on a broader comparative and historical dataset. First, the plantation economy and its afterlives deformed American working-class formation, giving succor to nativism and white racism, thereby making collective action on the European model impossible. Second, because America was a confederation of a neo-European colony with a slave society, local property rights were overdeveloped. This enfeebled the federal state, making it that much more difficult to redistribute resources from rich people in rich places to poor people in poor places (what Gilmore vividly calls “fiscal apartheid”). We would venture that these exceptional features of American political economy can explain both the outlying levels of violence in the United States and the penal (rather than social) response to it.

One could summarize this argument by noting that the racism of the American working class is our proximate explanation for the weakness of the American welfare state.24Of course, it cannot be the ultimate explanation for it. As we argue again later, this would require working-class racism to be some kind of ‘uncaused causer’ rather than a rationalization of the hierarchies of the American labor market, and ultimately slavery. It seems that Norton and Stein mostly agree with this part of the argument. But they seem to object to our view that racism matters principally in this way but less so in others. Specifically, they argue that we ignore the role of the racism of American politicians (and the public they cultivated) in the 1960s in driving the punitive policies that caused mass incarceration.

To be clear, we agree that many politicians who passed tough-on-crime legislation held racist views, and that these politicians often appealed to racism among their (mostly white) constituents in promoting such legislation. We also think that this kind of racism was probably causally relevant to the passage of those draconian bills (either in the weaker sense that it made them more draconian, or in the stronger sense that they wouldn’t have passed absent racism). But we are making the broader, stronger claim that a punitive response to the social crisis of the 1960s to the 1980s was an ineluctable consequence of the long-run weaknesses of American social democracy. If this is right, it means that racism’s central contribution to mass incarceration lies in its contribution to that weakness, thus setting the train in motion, rather than by winning white officials or electorates to any particular legislative agenda.

This is not, as it may seem to some, a distinction without a difference. There is strong evidence that even in cases where politicians and voters did not appear to be motivated by racial animus, legislation and judicial policy moved in much the same direction. As we have noted in other work, black voters and black politicians had remarkably punitive attitudes during this period. Norton and Stein suggest that these facts can be explained by the class position of black voters and politicians. It was in fact with the intention of demonstrating exactly this that we first began writing about mass incarceration together. Among other things, we collected tens of thousands of responses by black Americans to public opinion polls between the 1950s and the present to test precisely the hypothesis that Norton and Stein advance: that punitiveness in the black public was driven by middle-class elites who had grown ever-more-distanced from the progressive traditions of the civil rights movement. Yet we found no evidence that black elites were more punitive than the black poor. In fact, where differences were statistically significant, we found the opposite.

Certainly, we do not mean to deny that an America without racist politicians and racist politicking would have been a different America. But our claim is that it would be less different than Norton and Stein seem to believe. We insist on this point not simply for analytical reasons, but because if we are right, it has important implications for how to fight mass incarceration. By insisting on the necessary contribution of the racist attitudes of voters and politicians to the key events that gave rise to America’s carceral regime, Norton and Stein give credence to the widespread but misleading view that one can effectively fight mass incarceration by convincing (white) Americans to be less racist. There is nothing wrong with such efforts. Indeed, they may be capable of achieving many commendable goals. But reversing mass incarceration will not be one of them.

Again, as we emphasized in our conclusion to the original article, racism is central to the story of mass incarceration. But it mostly matters in ways that are less direct and more fundamental than the ways that have been the focus of the standard story. Principally, it matters because racism forestalled the only social force capable of winning the kind of redistribution that could have prevented or alleviated the rise of violent crime: a united white and black working class. While the weakness of the American working class has several causes, we think the historical roots of that weakness lie in the deforming effects of American slavery on American class formation.

Racism and Capitalism

Finally, what role does capitalism play in our account of racism? Norton and Stein suggest that we fail to take “racism seriously as an integral feature of capitalism.” To be clear, we agree with Norton and Stein that capitalism tends to reproduce racial inequality and thus racism. And we agree with Gilmore that this is primarily because capitalism systematically produces a population that is “surplus,” not relative to our capacity to sustain each other, but relative to the capacity of capital to profitably exploit labor. As a result of this, modern wage labor markets tend to be highly stratified, with the lowest strata perpetually cycling into unemployment—a “reserve army of labor.” Insofar as a person’s labor market fortunes depend on their skills and connections, and those skills and connections depend on social networks and kinship ties, then any group that starts out excluded from wealth and social status (e.g. due to a history of slavery and legal discrimination) will tend to see that exclusion reproduced over generations. If by racism we simply mean that certain groups are stigmatized insofar as they are disproportionately found at the bottom rung of modern labor markets, then this argument explains why racism is an “integral feature” of capitalist societies.

We would also insist that the question of what is to be done about prisons is not the only measure of our anti-capitalist imaginations, and perhaps not the one most attuned to the larger question of the capacity of American workers to bring about either reform or revolution.

Yet note that “racism” is typically used in a more specific sense than this. In Norton and Stein’s piece, for instance, “racism” really refers to the particular form that this stigma has taken in the United States. To understand these particular forms, abstractions about the nature of capitalism are insufficient. After all, capitalist societies differ widely in the degree to which each of the premises in the previous paragraph hold. Some labor markets are much more stratified than others. Some capitalist societies do more than others to break the link between a person’s connections and a person’s fortunes (e.g. through the public provision of education, housing and other primary goods). William Julius Wilson has argued that modern-day systems of racial stratification in the capitalist world are the product of the three very different kinds of large-scale population movements: slavery, European colonization, and migration.25See pp. 18-19 of Wilson, William J. Power, Racism, and Privilege. New York: Free Press, 1973. Because these encounters yielded different kinds of historic inequalities across the capitalist world, racial inequality and racism (and thus notions of race) look different in different places.

Maybe Norton and Stein would agree with these amendments to their formulation. After all, a focus on generic features of capitalism ignores the distinct role of particular capitalist states in establishing racial hierarchies, and the peculiar history of the American racial state anchors much of their own narrative. Moreover, they would surely accept that ours is a debate about why America incarcerates its racial minorities at exceptional rates, which obviously cannot be explained by something that America has in common with most other countries (i.e., capitalism). But if they do agree, it seems to us that they would have to concede what these points imply: to stress that racism is an “integral feature of capitalism” is either to observe a truism or to miss the point.

Materialism v. Idealism

Having said something about how we define racism, its role in the origins of mass incarceration, and its relationship to capitalism, it should be clearer where and how we disagree with Norton and Stein. We cannot, for instance, accept Norton and Stein’s definition of racism (following Gilmore) as “state-sanctioned and/or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” First, because that formulation fails to distinguish racism or racial inequality from other forms of group-based oppression (it is hard to think of any axis of social inequality that is not associated with unequal mortality rates). Second, because it tends to collapse racism into racial inequality, and thus conflates an explanation with a description. Third, because it presents a far too narrow account of those effects. Hispanic Americans, for example, today live longer than non-Hispanic whites (a gap that has recently grown due in part to the opioid epidemic) but it would be strange to conclude—as Norton and Stein’s definition implies—that they are beneficiaries rather than victims of racism.26The difference between the life expectancy of black and white women has also been steadily falling over the past decade (for people aged 65 and up the difference has already been effectively eliminated), due to rising mortality among middle-aged white women and falling mortality among black women. Of the 16 international classification of diseases (ICD-10) categories for which age-adjusted death rates of adult black and white women in the US can be reliably compared, 7 currently show higher mortality for white women, including diseases of the nervous, digestive, and respiratory systems, as well as mental disorders and external causes. White women also have higher mortality from suicide and drug and alcohol-related causes. See http://bit.ly/nortonstein_replication.

Nor can we accept Norton and Stein’s claim that we are “apologizing for racism” when we point out that white workers sometimes materially benefited (even if only individually or in the short-term) from racially segregated labor markets. Here Norton and Stein not only confuse an analytical for a moral argument, but also foreclose the kind of materialist analysis that has been the mainstay of Marxist writings on racism, from W.E.B. Du Bois and Stuart Hall to Noel Ignatiev and Gilmore herself.27While all these authors have pointed to ways that white workers materially and/or psychologically benefit from racism (albeit individually or in the short-term) a number of authors have attempted to empirically estimate wage premiums that white incumbents receive from racial restrictions in job-access: Edna Bonacich, “Advanced Capitalism and Black/White Race Relations in the United States: A Split Labor Market Interpretation.” American Sociological Review 41 (1976); Rhonda M. Williams, “Capital, Competition, and Discrimination: A Reconsideration of Racial Earnings Inequality.” Review of Radical Political Economics 19(2) (1987); and Carter A. Wilson, Racism: From Slavery to Advanced Capitalism (Sage 1996). Indeed, despite their frequent references to “materiality,” it is the idealism of Norton and Stein’s approach to racism that stands out to us. In treating it as a disembodied subject that “materializes itself” in the world, Norton and Stein reify racism. The notion that racism can become an independent power with a life of its own, one capable of not only haunting our social interactions but also embodying itself in our institutions, is an example of what Karen and Barbara Fields call “racecraft.” Such idealism is not only analytically misleading, but can also lead to some political dead ends.

In our view, American racial ideology is but a rationalization of the facts of American racial domination. As George Bernard Shaw is reputed to have said, “the American white relegates the black to the rank of shoeshine boy; and he concludes from this that the black is good for nothing but shining shoes.”28Cited in Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H. M. Parshley (New York: Random House, [1952] 1972), p. xxx. To argue that racist ideologies have independent power, as Norton and Stein do, is to believe that people can wield power over others by dint of their ideas. In reply, we insist the currency of power in social life is economic. It is economic resources that confer political, military, and cultural power. A group or person who lacks such resources can rarely wield power over groups or persons with more. In our article we quoted Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael): “if a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem.” This expresses the same, foundational insight: racism without power is simply prejudice. If racial inequality is to persist, it must be defended. And the success of this defense depends not on the prejudices of the dominant, but on the relative powerlessness of those they dominate.

This underscores why racism, in the sense of race-based prejudice or an ideology sanctioning racial domination, is proximately neither necessary nor sufficient to explain mass incarceration, despite the fact that the racial legacy of slavery is a necessary precondition of America’s carceral state. We argued (and Norton and Stein seem to agree) that only the large-scale redistribution of resources from rich people (disproportionately white) to poor people (disproportionately black) could have averted mass incarceration in the United States. Black Americans were powerless to win this magnitude of redistribution not because of the persistence of white prejudice but because of the enduring facts of American political economy. This remains true today: no matter how anti-racist white America becomes, racial equality will not result.29One obvious difficulty for accounts like Norton and Stein’s which emphasize the racist attitudes of white Americans is that the punitive turn occurred amidst significant attitudinal progress.

More optimistically, Ture’s formulation implies that prejudice will be no match for power. If a dominated group gains leverage, it should be able to challenge its subordination no matter what its oppressors believe. And how else would one explain the successes of Reconstruction and the civil rights movement, which won concessions from implacably racist opponents? Even if mass incarceration could be attributed to the campaigns of racist voters and politicians (and we have already suggested that this story is too simple), it would still be the case that this success depended in some fundamental sense on the incapacity of black Americans to challenge these bigots. In a counterfactual America in which black Americans were more powerfully positioned, white racists could have had no such success.

In the end, like many other critics of the carceral state, Norton and Stein tell a story in which the prime movers are the bad ideas in white people’s heads, rather than the relative capacities of working-class and black Americans. But if mass incarceration is to be defeated, it will be because the disproportionately black poor will have gained leverage over the disproportionately white rich. It will not be because we will have turned racists into anti-racists.

Conclusion

Norton and Stein’s response is almost as long as our original article. Rather than explore all the issues they raise we have decided to dwell on what seemed to us to be most important. However, just as we began with a note on crime data, we’d like to conclude with a note on the Methodenstreit that Norton and Stein wage against our “bourgeois scientific categories,” and specifically our use of counterfactuals, since it may also reveal something about the political conclusions that may be drawn from our argument.

Norton and Stein seem to think that counterfactuals are a form wishful thinking—hazy “should-have-beens”—so they doubly misread our comparison of the United States to Europe as evidence that we believe (1) that a European-style welfare state was a possibility in the US of the 1960s, and (2) that it would have been politically desirable (that we are “bemoaning a lack of social democracy”). In fact, we (the authors of the article) disagree with each other about (2) but agree on the implausibility of (1).

So why do we speculate about a scenario that was highly improbable? For the simple reason that speculative counterfactuals are a necessary corollary of any causal claim. For instance, when Norton and Stein suggest that the racism of Southern politicians presented a roadblock to Great Society programs, they are imagining an implicit counterfactual: that if those politicians had been less racist (or had less power), then the Great Society would have expanded further. This counterfactual is not realistic (it is hard to imagine non-racist Southern white politicians in the 1960s), but the realism of the counterfactual is not at all the point. The question is what conclusion can be realistically derived from that unrealistic counterfactual. The difference between our argument and Norton and Stein’s is not that we rely on counterfactuals but that we make them explicit.

Yet Norton and Stein may be misreading us in this way because they themselves appear to be committed to both (1) and (2), or rather, their political commitment to some version of (2) has led them to defend some version of (1). They write “we agree that a vibrant social welfare state would have undermined the nascent system of mass incarceration,” a possibility they associate with “social movement struggles for a broadened welfare state in the 1960s.” But here, where Norton and Stein think they agree with us, is actually where we disagree. In our article, we explicitly denied that the 1960s was “a missed moment” when popular movements could have challenged the construction of the carceral state.30We specifically argued that “[l]ess people would be languishing in American prisons had the Left won the battles it lost, but the struggles of the 1960s were not decisive.” This is because we think the fundamental causes of mass incarceration were by then baked into American economic and political institutions. It is Norton and Stein, not us, who need to make the case that the social struggles of the 1960s could plausibly have built social democracy in America.

More generally, while analytical arguments certainly have normative implications, they are never decisive on their own. We know this because the two of us have come to the same analysis of American mass incarceration without reaching the same normative and political conclusions about it.

Laying out our differences would require a separate article (or two!), but Norton and Stein inadvertently put their finger on them in their critique. They criticize and quote out of context sole-authored pieces in which, on the one hand, one of us points to the limited potential of calls for “prison and police abolition” to achieve badly needed reforms to America’s criminal justice system, and on the other, one of us describes police reforms (specifically diversifying police forces) as an insufficiently radical response to racist police violence. Quite apart from the problem that neither view can be found in our Catalyst piece, Norton and Stein do not seem to be able to keep their story straight: are we too reformist or too radical for their tastes?

Norton and Stein try to get around this inconsistency by implying that what unites these contradictory positions is that they are both insufficiently attentive to a singular “Black politics,” which they tend to conflate with an unspecified notion of “abolition.” Yet this sleight of hand is as politically naive as it is racially reductive. It elides sharp differences of opinion among black people (which we have described in detail elsewhere), as well as among those who call themselves “abolitionists.” The latter term has been applied to everything from specific calls for decarceration and restorative justice to a broad-based strategy of “non-reformist reforms,” up to and including an immediate revolutionary tactic of destroying prisons. While the two of us would situate ourselves in quite different places on this spectrum, we would also insist that the question of what is to be done about prisons is not the only measure of our anti-capitalist imaginations, and perhaps not the one most attuned to the larger question of the capacity of American workers to bring about either reform or revolution.

Nonetheless, if one did seek to derive normative or strategic conclusions from what is, in the end, an analytical article, we think they might be both more and less pessimistic than the conclusions of Norton and Stein. More pessimistic in the sense that if we are right, there is presently little opportunity for a substantial reversal of the nightmare that is America’s prison system. The problem of mass incarceration is deeper and more intractable than an analysis of misguided criminal justice policy and racist politicking in the 1960s will allow; it is an indictment of America’s entire political economy. Less pessimistic in the sense that if workers in the United States ever achieve the leverage to disrupt that political economy, then we may be able to start dismantling the American gulag here and now, before the revolution or the anti-racist rapture. This is because we think the racist ideas in white people’s heads will be no match for a mass movement that puts power in the hands of ordinary people. And thus, the end of mass incarceration is currently unlikely – but not impossible.