The US Kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro

Interview With Geo Maher

January 27, 2026

On January 3, 2026, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was kidnapped alongside his wife, Cilia Flores. Both were transported to the heart of the US empire, the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, where they are now being held captive (as “a prisoner of war,” in Maduro’s own words). The incident has exposed the United States’s naked imperialism with members of the Trump administration espousing a world order based on raw power and national interests on mainstream media outlets, including Stephen Miller’s declaration to CNN that “we set the terms and conditions” in Venezuela.1“Stephen Miller says US is using military threat to maintain control of Venezuela,” video, 15:34, CNN, January 5, 2026, https://www.cnn.com/2026/01/05/politics/video/senior-white-house-aide-stephen-miller-says-us-military-threat-to-maintain-control-of-venezuela-digvid.

The future of Venezuela, and the region more broadly, will be determined by what happens next. With help from other members Spectre‘s editorial board, Maga Miranda interviewed Geo Maher, author of We Created Chávez and Building the Commune, for his expert opinion on the issue.2George Ciccariello-Maher, We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822378938; George Ciccariello-Maher, Building the Commune: Radical Democracy in Venezuela (New York: Verso, 2016).

First things first, we should be absolutely clear that the military incursion into Venezuela and the kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores had nothing to do with either narcotrafficking or democracy. Most of us probably already knew this, but the Trump administration has done us the favor of confirming it. The DOJ immediately walked back claims about Maduro being the leader of the fictitious Cartel de los Soles, while Trump brutally snubbed opposition leader María Corina Machado’s regime aspirations, all while making perfectly clear that the intervention was actually about Venezuelan oil and the projection of US power in the region.3Charlie Savage, “Justice Department Drops That Venezuela’s ‘Cartel de los Soles,’ Is an Actual Group,” New York Times, January 5, 2026, https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/05/us/trump-venezuela-drug-cartel-de-los-soles.html; Venezuela Investigative Unit, “US Sanctions Mischaraterize Venezuela’s Cartel of the Suns,” InSight Crime, August 1, 2025, https://insightcrime.org/news/us-sanctions-mischaracterize-cartel-of-the-suns-venezuela/; “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Safeguards Venezuelan Oil Revenue for the Good of the American and Venezuelan People,” The White House, January 9, 2026, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2026/01/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-safeguards-venezuelan-oil-revenue-for-the-good-of-the-american-and-venezuelan-people/. In other words, this was an attack based on the thinnest possible pretext.

Magicians have a technique called “misdirection,” where they do something to distract with one hand while the other hand is actually doing the trick. We’re more than familiar with this from the sorts of lies that were rolled out to justify the Iraq War, for example—and we hear lots of the same rhetoric today. But it’s also the laziest and most brazen form of misdirection possible; even still, we’ve seen liberals and even some sectors of the left parroting some of these claims—in particular, the idea that Venezuela is a dictatorship. If we know this invasion had nothing to do with democracy, then why are we even talking in those terms? It shows just how easily misdirected we are by those in power, even when they are being brutally honest about their own motivations.

What explains this brutal honesty of the Trump administration? Here I think the answer lies in the strategy of projection itself, which both Trump and Marco Rubio have emphasized, but also the two different audiences this strategy speaks to. The global hegemony of the United States is crumbling, and quickly—Trump is more honest about this than most liberals. So his strategy is to shore up American power materially by safeguarding access to natural resources from oil to rare earth minerals while simultaneously preventing them from falling into the hands of global adversaries—China in particular. The contradiction here is that the United States lacks the brute military capacity to do so, but also that, because of the long-term occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, most Americans—a key sector of the Trump base in particular—have no appetite to even try.

This is where Trump’s “projection” comes in, which we should understand in the dialectical sense rather than the psychoanalytical sense—that is, as a sort of putting the cart before the horse. Whether through tariffs or precisely coordinated special-forces raids, the point is to perform power in a spectacular way—to act first and negotiate later, with the action resetting the terms of the negotiation. This is why the US government can crow loudly about opposing forever wars while upholding the Monroe Doctrine and US dominance in the western hemisphere and embracing a strategy of provocative and aggressive action to reassert that dominance. It’s a sort of perverse guerrilla warfare of a decadent empire.

Now, the psychoanalytic piece is never far below the surface, and we know that Trump’s father inculcated him with the strategy of repeating untruths so often that they eventually become reality that we see today. Unfortunately, the left has its own projections to spare. We’re so invested in an image of revolutionary purity that we not only neglect the real difficulties of making a revolution, while simultaneously assuming the worst possible motivations about both those in power in Venezuela and the hundreds of thousands struggling on the ground to make that revolution a concrete reality against all odds.

Solidarity isn’t valuable when things are going well—it matters most when the going gets tough, as it inevitably does.

There’s longue durée and then there’s longue durée… So first, we need to understand the Bolivarian process in the long arc of about two hundred years—of what independence and regional unity meant for Venezuela and the broader Gran Colombia. This means understanding—as Greg Grandin shows so well in America, América—that US settler society has long viewed Venezuela as a challenge to its own Protestant settler fascist model.4Greg Grandin, “Tar Wars,” Nation, January 6, 2026, https://www.thenation.com/article/world/venezuela-tar-wars/. See also Greg Grandin, America, América: A New History of the New World (New York: Penguin, 2025). More narrowly, we need to be absolutely clear that the Bolivarian Revolution didn’t begin with Hugo Chávez Frías, even if he stepped into the space of historical possibility to play a crucial role. Instead, this is a process that grew out of the armed guerrilla struggle of the 1960s and ’70s, the emergence of territorialized community struggles in the 1980s, and the mass rebellion against neoliberalism that was 1989’s Caracazo.

Chávez had already been conspiring with other leftists in the military, and his brother Adán was affiliated with the armed underground. But the Venezuelan masses caught everyone off guard when they responded furiously to the neoliberal bait-and-switch of then-president Carlos Andrés Pérez, who had promised to resist the Washington Consensus but ended up following it to the letter. When he liberalized gasoline prices, Venezuelans woke up to higher bus fares. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back and thousands rioted, rebelled, looted, and burned Caracas and other cities for a week.

Nothing sets history into motion quite like a riot—we know this perfectly well today and, in 1989, the Venezuelan people broke their own history in two, destroyed a repressive two-party system, and made possible everything that has come since. All of which locates this process in a longer timeframe but also a broader scope. Venezuela was on the cutting edge of the historical boomerang against the neoliberal wave that devastated Latin America before landing with similarly brutal effects in the Global North. It’s only by fully grasping the historical texture of this prehistory that we can then analyze the Bolivarian process in power as part of a longer historical process rather than as its beginning (and much less its ending).

Here we can speak of roughly three stages. The first phase, running from around 1999 to 2005, was characterized by laying a new democratic foundation, rewriting the constitution, and reclaiming natural resources. These resources were then dedicated directly (via the Mission System, which sought to skirt the state bureaucracy) to a broad range of social welfare programs that dramatically reduced poverty, provided universal access to healthcare and education, and built millions of housing units. The second phase, from around 2006 to 2012, sought to build on these progressive accomplishments through a far more ambitious project that we could more readily understand as “revolutionary.” The goal in this phase was to transform the entire political structure through the expansion of grassroots councils and communes, with the ultimate goal of putting everyday people in charge of their own lives, producing what communities actually need, and replacing the traditional liberal-bourgeois state with a new socialist “communal state” (this idea, to be clear, was not invented by Chávez, but dated back to the late armed struggle).

The third phase (roughly since Chávez’s death) has been characterized by a profound economic, political, and social crisis. While this crisis began with the mismanagement of the exchange rate and the corruption that accompanied it, this could have been corrected were it not for other factors, including the open and violent aggression and sabotage that Maduro immediately saw from the United States and the Venezuelan opposition forces. And here we need to be absolutely clear: the single most important cause of the crisis, and certainly of the catastrophe, has been the absolutely brutal and murderous sanctions regime instituted by both Barack Obama and Donald Trump.5Mark Weisbrot and Jeffrey Sachs, Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela (Washington DC: Centre for Economic and Policy Research, 2019), available at https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/venezuela-sanctions-2019-04.pdf. For more than a decade now, Venezuela has been facing a hybrid war that has devastated oil production, crippled the economy, starved the population, provoked a mass emigration crisis, and forced the Maduro government to take a range of desperate and defensive measures in an attempt to stabilize the economy and feed its people.6Claudia De La Cruz, Manolo De Los Santos, and Vijay Prashad (eds.), Viviremos: Venezuela vs. Hybrid War (New York: International Publishers, 2020).

Like many others, I have been skeptical and even critical of certain policies or strategies taken by the Maduro government—for example, the empowerment of certain military sectors and the overtures toward both the private sector and foreign investors. But I also know that those decisions are being made under severe duress. The reality is that if we don’t understand the severity of the sanctions, we won’t understand anything at all. And any attempts to second-guess what the Maduro government “should have done” needs to begin from the terrain on which it was actually and concretely maneuvering.

Again understood through this long historical frame, both the Bolivarian project and the opposition to it have always been transnational. On the one hand, this is a key lesson of early dependency theory and revolutionary struggles alike: that while the goal is to “delink” from the global capitalist system, strategies of go-it-alone autarky or socialism in one country are incredibly difficult (if not doomed). Chávez’s response to these challenges was to develop institutions of regional integration: Latin American alliances, lending institutions, and trade zones that would strengthen the bonds of solidarity among progressive and leftist governments while providing both concrete economic support and a political safety net for momentary crises. This meant lending institutions that didn’t come with the strings of IMF/World Bank structural adjustment, but also the fact that, during the 2000s, progressive governments in Chile and Brazil were able to underwrite more radical experiments in Bolivia and Venezuela.

Global capital and US imperialism has sought to dismantle that unity right from the start through coups and quasi-coups, by funding opposition electoral campaigns, and by facilitating the emergence of a continent-wide fascistic youth movement under the leadership of Colombian narcofascist Álvaro Uribe. While this attack on the Pink Tide has always been bipartisan—with Obama and Hillary Clinton funneling aid to the Venezuelan opposition through USAID and facilitating the 2009 coup in Honduras—Trump himself has taken this task seriously, supporting the quasilegal rise of Bolsonaro in Brazil, far-right candidates in Argentina and elsewhere, and now a neofascist in Chile. These are dark times for regional unity.

But all is not lost, and we have also seen the emergence of a new Pink Tide from the most unexpected quarters, specifically the development of a leftist hegemony in Mexico—“so close to the United States, so far from God” in Porfirio Díaz’s phrase—and the beginning of the same in the deeply structurally fascist Colombia. Only time will tell whether Trump’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine will seek to target these examples more directly, but his aggressive moves and dismantling of US soft power in the region is a risky strategy for sure.

Is the Maduro government as wildly popular as Chávez was in his heyday? Of course not. But setting this as our baseline guarantees that we will misunderstand reality. Venezuela has been in a sustained economic crisis for well over a decade, although recent years have seen more stability, as government reforms have improved conditions on the ground. Any sustained economic crisis will mean less support for those in power. Not only should this be expected, but the stated objective of US sanctions is simply to punish the people until they turn against their government.7Jeff Stein, Ellen Nakashima, and Samantha Schmidt,“Trump White House was warned sanctions on Venezuela could fuel migration,” Washington Post, July 26, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/07/26/venezuela-crisis-immigration-us-sanctions-trump/; De La Cruz, De Los Santos, and Prashad (eds.), Viviremos. This was the US strategy during the Contra War against Nicaragua’s Sandinistas as well: to unleash bloody terror until the people vote, with a gun to their head, to end the revolution–which they finally did in 1990. It’s incredibly foolish to interpret that result, or any election under the duress of sanctions and war, as a victory for democracy.

So yes, of course the class composition of both opposition voters and opinion has shifted, because those bearing the brunt of the crisis are not the richest exile communities—even if those exiles remain the loudest and still take up the vast majority of the airtime. Of course, this has meant that a sector of less politicized Venezuelans have swung toward the opposition. But as the best analysts on the ground have always made clear, these electoral swings are largely economic, often temporary, and do not in any way constitute an endorsement of the policies of the Venezuelan opposition—which rarely offers any policy proposals at all.8Ociel Alí López, “In Praise of Chavismo,” Venezuelanalysis, December 8, 2015, https://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/11761/. This is no accident either, since over the course of twenty-five years Chavismo has become hegemonic, meaning that almost everyone believes that the oil belongs to the people and should be used to their collective benefit. This means that the opposition’s long-held political positions—a return to neoliberalism, privatization, and austerity—are deeply unpopular, so they rarely say them out loud. They simply blame the government for all the effects of the crisis, and seek to win power by default.

This fact becomes especially obvious in moments like the present: polls show that scarcely 3 percent of Venezuelans support military intervention, while many self-styled “leaders” of the opposition openly celebrate the attacks on January 3.9Steve Ellner, “With Trump, Polarization Among Venezuelans Reaches New Heights,” NACLA, October 20, 2025, https://nacla.org/with-trump-polarization-among-venezuelans-reaches-new-heights/. Instead of celebrating in the streets, as some on the right seem to have hubristically expected, many opposition voters decried the kidnapping of their head of state by a foreign power, while many others expressed fear and anxiety over what was to come. The response of many more, in the words of former communes minister Reinaldo Iturriza, was one of silent mourning which, he writes, is difficult to interpret but which we must work to understand.10Renaldo Iturriza López, “La última palabra,” saber y poder, January 11, 2026, https://saberypoder.net/2026/01/11/la-ultima-palabra/.

Resistance is there, for sure, in the thousands of communes and grassroots organizations that are doubling-down and digging in for struggle in the long term.11“Venezuela. Comunas retoman la defensa popular del país tras los antentados y mantienen la producción del país,” Resumen Latinoamericano, January 12, 2026, https://www.resumenlatinoamericano.org/2026/01/12/venezuela-comunas-retoman-la-defensa-popular-del-pais-tras-los-atentados-y-mantienen-la-produccion-del-pais/. These are organizers who have always seen their primary goal as the defense of a process and not a government, but who also understand that—for now—the process relies on the government. But in the short term, the question is: resistance against who? How do you resist an enemy thousands of miles away?

I think you’re absolutely right that these are conspiracy theories and, once again, it’s embarrassing to see some on the left turning to conspiracy, stoking divisiveness, and assuming the worst about the leadership, rather than analyzing the conjuncture materially. What do we know about the material reality of the situation? That the US military brought an overwhelming military overmatch to the January 3 operation, deploying 150 aircraft, highly-trained special forces, and unprecedented logistical capacity to what was essentially a smash-and-grab operation. We know that there was a fight—in fact a massacre, particularly of those Cuban soldiers who resisted.

Moreover, we know that the threats against the Bolivarian government didn’t end on January 3 and that this show of force was intended to shape an ongoing process of negotiation in a context where neither boots on the ground nor a puppet government are likely to see the same level of success. In this context, yes, acting president Delcy Rodríguez—after clearly denouncing the kidnapping—has responded in a remarkably conciliatory way. But while it’s true that everyone—particularly in Venezuela—is trying to read the tea leaves of these statements, it’s also important not to over-read the situation and fall prey to conspiracy theories, which I think is definitely happening to some on the left.

Delcy Rodríguez is acting exactly how someone would act in this kind of situation if their goal is to avoid a threatened second-wave attack, and especially if their concern is to stabilize the economy and leverage the current situation to get the sanctions lifted. On the level of Occam’s razor, none of this requires over-complicated interpretation. What this strategy means for the medium and long term is another question, as is the broader question of the different and even contradictory motivations, values, and interests circulating within Chavismo. Believe me, as someone who has written two books about these contradictions: they are important. Do I think the Rodríguez siblings, Diosdado Cabello, or Vladimir Padrino López represent the most radical segment of the Bolivarian Revolution? No, I don’t. Is it possible that they’re more concerned with saving their own skin than safeguarding the Revolution? Yes, it is.

But on a fundamental level, these are not the essential questions we need to be asking at this moment. And what those self-styled critics on the left won’t tell you is that the current government, despite internal contradictions, has been working to expand the scope and power of the communes for years. Just days before the kidnapping, Maduro himself was praising the consolidation of communal power, which we have seen expanding all across the country and has been well documented by the Anti-Blockade Observatory.12“Nicolás Maduro destacó consolidación del Poder Comunal en Venezuela,” Prensa Latina, December 29, 2025, https://www.prensa-latina.cu/2025/12/29/nicolas-maduro-destaco-consolidacion-del-poder-comunal-en-venezuela/; Chris Gilbert and Cira Pascual Marquina, Resistencia comunal frente al bloqueo imperialista: Rutas Amazonas (Caracas: Observatorio Venezolano Antibloqueo, 2025), available at https://observatorio.gob.ve/producto/resistencia-comunal-frente-al-bloqueo-imperialista-ruta-amazonas/. What’s more, the current commune minister—Ángel Prado, who I got to know while writing Building the Commune—is an incredible revolutionary and a comrade. In the past, he survived assassination attempts by corrupt Chavista local leaders, and he’s part of this government. He isn’t naive or stupid, nor are the hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of others who know that any possible revolution must inevitably come through Chavismo, not against it.

In fact, in the days and weeks since Maduro’s abduction, the government has doubled down on communal production, adding 215,000 hectares to a new plan for strategic food production and convoking a nationwide congress on the communal economy for February 4—the anniversary of Chávez’s 1992 coup.13“Comunas impulsan el desarollo de las fuerzas productivas en el territorio,” Ministerio del Poder Popular para las Communas, January 21, 2026, https://www.comunas.gob.ve/2026/01/21/comunas-impulsan-el-desarrollo-de-las-fuerzas-productivas-en-el-territorio/. English speakers can read an entire issue of Monthly Review published just last year on the subject, featuring an interview with Prado.14Chris Gilbert and Cira Pascual Marquina (eds.)., Monthly Review 77, no.3 (July-August 2025): https://monthlyreview.org/9980077032025/.

Despite all the discourse, the politics of oil in Venezuela remain poorly understood, so here are some basics: For the past century, Venezuela’s economy has revolved primarily around oil exports, which, as many economists and others have long observed, is both a gift and a curse—what one Venezuelan oil minister famously described as “the devil’s excrement.”15“The Devil’s excrement,” Economist, May 22, 2003, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2003/05/22/the-devils-excrement. It’s a curse because it introduces profound distortions into a country’s economy, but what’s less recognized is that this is basically an amplification of deeper colonial dynamics according to which resource extraction transforms every aspect of a society and turning toward the global market means turning away from internal needs.

What this meant for Venezuela is absolutely stark: by the 1970s, some 90 percent of the population lived in cities and 90 percent of food was imported. There’s a clear connection between the two: you can’t eat oil. So long ago, Venezuelan revolutionaries within sectors of the armed left began to formulate a radical alternative that would seek to “sow the oil,” to borrow a famous phrase, reclaiming oil rents to invest in diversification and restructuring the economy in an effort to roll back these colonial legacies. Note that there has never been a significant “anti-extractivist” tendency in Venezuela as we have seen in Bolivia and elsewhere—the consensus was always to use the oil to move beyond oil. This radical theory of oil was central to Chavismo, which immediately reconstituted OPEC to drive up oil prices dramatically, thereby—and here an important side note—contributing more to the development of green alternatives in the global north than most of our movements combined.

Under the banner of “food sovereignty,” agricultural production under Chávez increased, in some cases dramatically. But people also started eating more and still both wanted and needed a whole range of imported goods. And if it’s incredibly expensive to roll back centuries of colonial economics when it comes to food cultivation, it’s even more so in the case of industrial and especially high-tech products—this is the most basic fact of the global dependency trap: you still need to import expensive goods. So economic diversification away from oil made some progress under Chávez, but it was never enough, and it was incredibly difficult and expensive to sustain. In every crisis and every electoral season, the cheaper and more effective option was always to use oil revenue to stock the supermarket shelves.

I know that’s a roundabout way to get to the question of the sanctions, but it matters, in part because it explains just how easy it was for the US to strangle Venezuela. A reliance on export sales and food imports is a massive political liability and a key economic chokepoint, so when the oil price began to fall, there was less money to feed the people. This was true even before the sanctions. In fact, there was a moment when the communes proposed taking control of the import sector directly given how ripe it was for private-sector corruption. Sadly, this didn’t materialize, leaving Venezuela vulnerable and making it easy for the US government to set a starvation campaign against the Venezuelan people into motion. As Weisbrot and Sachs note, these sanctions caused some forty thousand deaths in just their first two years.16Weisbrot and Sach, Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment.

People don’t really understand how severe these sanctions are and how they rebound on the oil sector to create a sort of death spiral. The United States has effectively blocked not only Venezuela’s ability to sell oil to itself and its allies, but has also shut Venezuela completely out of SWIFT (the central network for global financial transactions). This means that Venezuela has to pay wartime insurance on shipping, send it halfway across the globe to Russia or China where it’s sold at a deep discount, and somehow figure out a way for the financial transaction to be carried out by other means in order to even sell its oil. The effects have been ruinous.

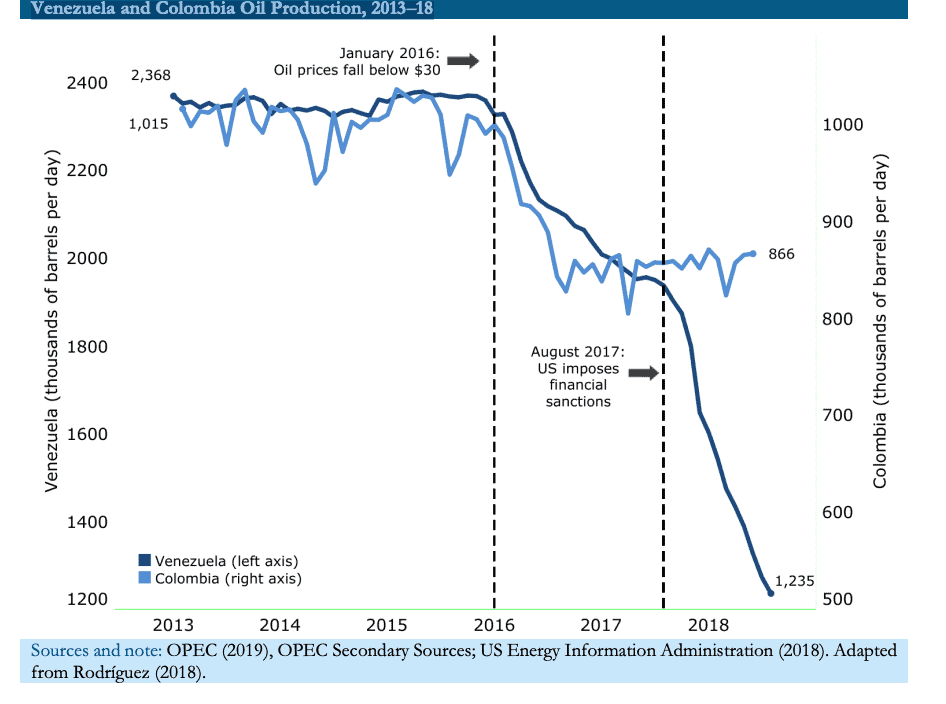

And it goes further: all production in Venezuela, and oil production in particular, relies on expensive parts and chemical inputs that also have to be imported and paid for. So when the Trump administration blames the Maduro government for the decline of the oil industry, this is yet another blatant lie: oil production began to decline across the board internationally with the sharp decline in oil prices, but Venezuelan oil production crashed completely when the sanctions made it impossible, as this image from Weisbrot and Sachs makes clear:

The kidnapping of Maduro and Flores and the broader blackmailing of the Venezuelan people has everything to do with oil, but it also has to do with the broader politics and the meaning of oil and the other natural resources like key rare earth minerals that Venezuela possesses. It’s about accessing those resources, denying them to competitors like China and Russia, and violently shoring up the western hemisphere as a crutch for a failing empire.

Venezuela’s communes represent the only actual solution to the longstanding coloniality of Venezuela’s economy, and the pernicious impact of oil in particular. If colonialism, and oil in particular, distort the economy toward external markets and pressures, the communes point in the opposite direction” toward what later dependency theorists called “endogenous development”; toward food sovereignty; toward transforming the economy by prioritizing the needs of the people, not global capitalism; and toward the actual, substantive independence that these all bring. The communes contribute to, and even represent, the ultimate horizon of revolutionary Bolivarianism because they provide a mechanism for communities to determine their own priorities and needs and work collectively to meet them.

Now, there’s a tension around communal power when it comes to the crisis, which I had already discussed in Building the Commune, and which is deeply related to the contradictions posed by the oil economy itself. When there was lots of oil money circulating, Chavismo was able to—and in fact did—dedicate significant resources to supporting and funding the expansion of communal production. But much like we see in the US nonprofit sector, for example, this can also lead to what economists would call rent-seeking behavior, with communes forming because of the resources available and the needs of the government rather than their own needs—there were so many textile communes producing t-shirts at one point! But when economic crisis hits, and particularly the kind of crisis that makes importing goods nearly impossible, things change dramatically.

Many communes collapsed immediately, but people still needed to eat. Those that survived began to provide directly what people most desperately needed, much of which was directly delivered to the population through new government-run distribution networks. In other words, nothing made clearer to the Venezuelan government that it needs the communes than the crisis itself. We would never celebrate this kind of baptism by fire—and something very similar happened in Cuba during the “Special Period” after the fall of the Soviet Union—but it’s an unmistakable tension and feature of reality. And based on observations by comrades on the ground, there’s reason to believe that the communes have been fortified in recent years thanks in part to the emergency stabilization programs of the Maduro government.

I began with the question of selective solidarity, and it’s worth ending there too. There was a time when it was easy to support the Venezuelan revolution. Through CITGO, Venezuela distributed free heating oil to working-class people in the Bronx and Indigenous communities across the United States. After Hurricane Katrina, Chávez offered emergency aid, which was refused. And at the height of the Bolivarian process, it was easy and relatively cheap to visit Venezuela to see the process in real time and engage directly with movements on the ground, and for Venezuelan organizers to visit the United States on speaking tours. Those times are long gone, and solidarity has become much more difficult in theory and in practice.

But again, we don’t need solidarity when it’s easy, we need it when it’s hard! Not solidarity with leaders or presidents, but solidarity with communities in struggle. Not the kind of coercive solidarity that we threaten to withdraw whenever we disagree with this or that policy of the Venezuelan government, but a solidarity that gives the revolutionary process some strategic breathing room. Critique is necessary, but our critique must be grounded in a material understanding of the terrain and the options on the table, and with a respect for strategy in a context where we don’t have all the information. To be clear, there are plenty of critics on the ground in Venezuela of all political stripes. Throughout the Venezuelan process, we have seen a sort of repetition of longstanding strategic debates between what we could roughly see as more Trotskyist and more Stalinist tendencies and strategies, even if they don’t always go by those names.

In Venezuela as elsewhere, the strength of Trotskyist and other far-left tendencies has been a spirit of critique, whereas their downfall has been their difficulty, and even inability, to grasp a revolutionary process as process—and an incredibly difficult and uneven process at that. The strength of more “Stalinist” tendencies is their understanding that the socialist transition is complex and combative, and that it means making hard decisions under what will inevitably be adverse circumstances; their clear weakness in Venezuelan and elsewhere is an overly cautious and conservative approach that prioritizes stability over the creative intervention of the kind of mass struggle that made the Bolivarian process possible from the beginning.

Those debates are ongoing on the ground. We in the United States don’t get to tell Venezuelans how to make their revolution. To be clear, I don’t say that from the perspective of an abstract anti-imperialism. “Hands off Venezuela” is important but it isn’t enough, because we aren’t just against US intervention in Venezuela, as we should be against it everywhere. We’re for the truly revolutionary political project that Venezuela has offered to the world, which is geared toward direct democracy, a self-managed economy, and community power against global capitalism and imperialism. We in the United States should be doing our best to not only fight fascism in the streets but also to build a revolution in the belly of the beast as well. And when we do so, we’re doing the same fucking thing that Venezuelans are.

When we talk about building communities without police, we’re talking about stable and flourishing egalitarian communities where our needs are met and we collectively keep ourselves safe. And when we fight ICE stormtroopers in the streets and refuse to let them kidnap our neighbors and tear our communities apart, we’re doing our part to build and wield collective power against fascist terror. That’s exactly what Venezuelans are fighting for, and on top of that, they’re fighting against US imperialism to have the freedom and opportunity to build upon that revolutionary vision. But doing so is fundamentally a process, and I hate to break it to people: but it’s a long and difficult process that will inevitably be characterized by protracted and bloody struggle against the most vicious enemies of progress.

Regardless of our own assessment of the virtues of vices of the Venezuelan leadership, or our own sectarian commitments, our tasks for the coming weeks, months, and years should be perfectly clear:

- To press for an immediate War Powers Resolution that would halt all funding of aggression against Venezuela;

- To demand the immediate release and repatriation of Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores; and most importantly,

- To demand–and fight for–the immediate lifting of sanctions so Venezuelans can decide for themselves—through mass struggle and not with a gun to their heads—what they think the Bolivarian Revolution should mean moving forward.