Labor’s Upsurge and the Search for Workers’ Power

Will the Strikes Continue?

November 16, 2023

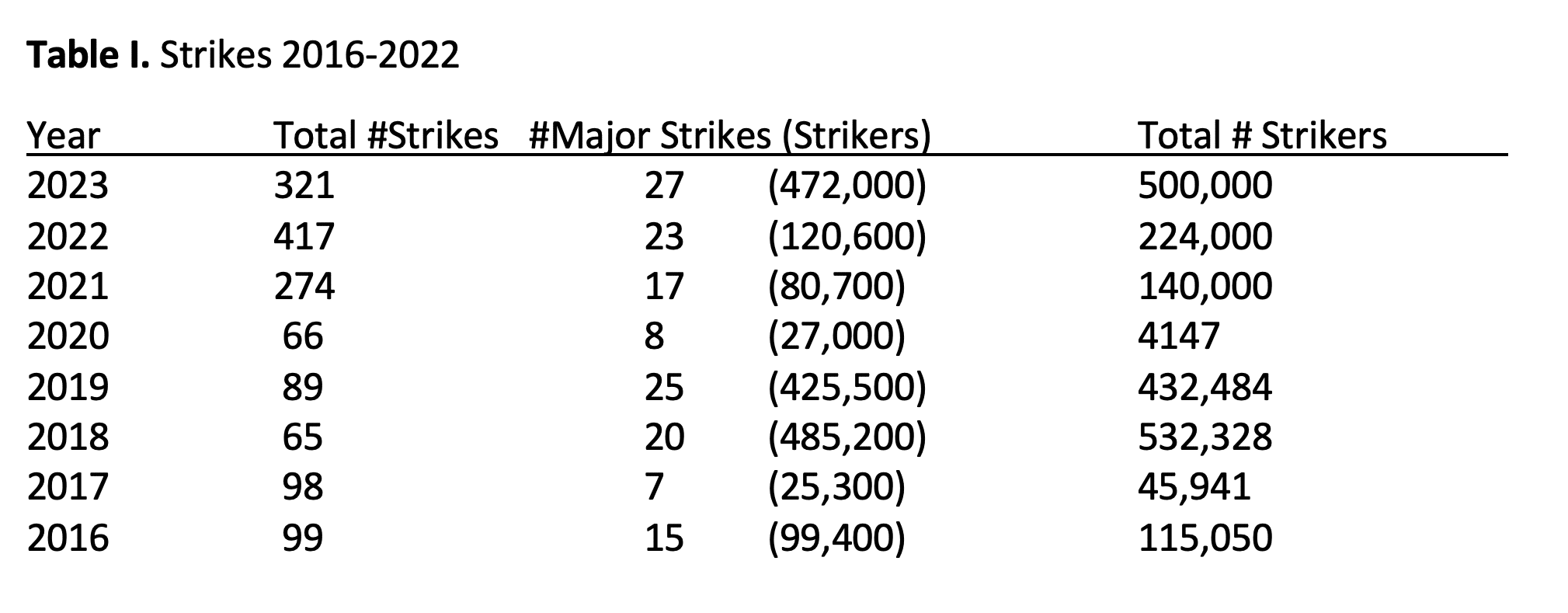

From the Red State Teachers’ Strike Wave through the “Hot Labor Summer” and into the fall of 2023, more and more union members are striking. As of early November, an estimated half a million workers had walked off the job with more likely to come. That’s still fewer strikes than the 532,238, mostly teachers, who struck in 2018, but the upward trend in the number of workers taking to the picket line since the pandemic froze the economy in 2020 is unmistakable. On average, strikes are bringing greater gains in wages, and even new dimensions in bargaining, as more workers seek to deal with new technology and industry changes. Furthermore, the more union members walk off the job, the more average Americans approve.

The annual August Gallup polls of how many people support unions and strikes show that approval of unions increased by one percentage point a year from 61 percent in 2017 to 65 percent in 2020 and then jumped three points in 2021 to 68 percent just as the number of strikes leaped from 66 in 2020 to 274 in 2021 and that of strikers from 41,747 to 140,000. Multi-point jumps in all these figures continued into 2022 when the number of strikers hit 224,000 according to the Cornell ILR Labor Action Tracker, while approval hit a high of 71 percent before levelling off at 67 percent in 2023. This rise and fall in approval was due entirely to a sudden and suspicious rise to 56 percent in 2022 and then drop in approval by Republicans back to 47 percent in 2023. The 67 percent approval in 2023 was, nevertheless, well above the average for any decades since the 1960s. This year, Democrats approved by 88 percent and independents by 69 percent. This was followed by half a dozen polls showing even higher levels of support for unions.

The approval of unions was accompanied by that for strikes. That is, while liberal and neoliberal economists and politicians expressed concern about strikes knocking the fragile economy off the rails, the majority said, “Right on, sisters and brothers.” The Pew survey showed large majority support for autoworkers and screen writers and actors, though not all of these were on strike when the poll was taken. A Reuters/Ipsos poll taken in September, when the Hollywood writers and actors were on strike and the UAW’s escalating strikes were in progress, showed fifty-eight percent of those surveyed supported the auto workers and fifty-nine percent supported the Hollywood workers. When asked, “Which side do you support?,” seventy-eight percent supported the autoworkers and seventy-six percent the screen writers. In virtually all the polls that ask which side in the dispute do you support, those favoring the bosses never exceeded twenty-five percent. So, we are not just seeing some sort of liberal approval of collective bargaining as an institution, but of workers in action against capital in a “Which Side Are You On?” moment.

Who Is Striking?

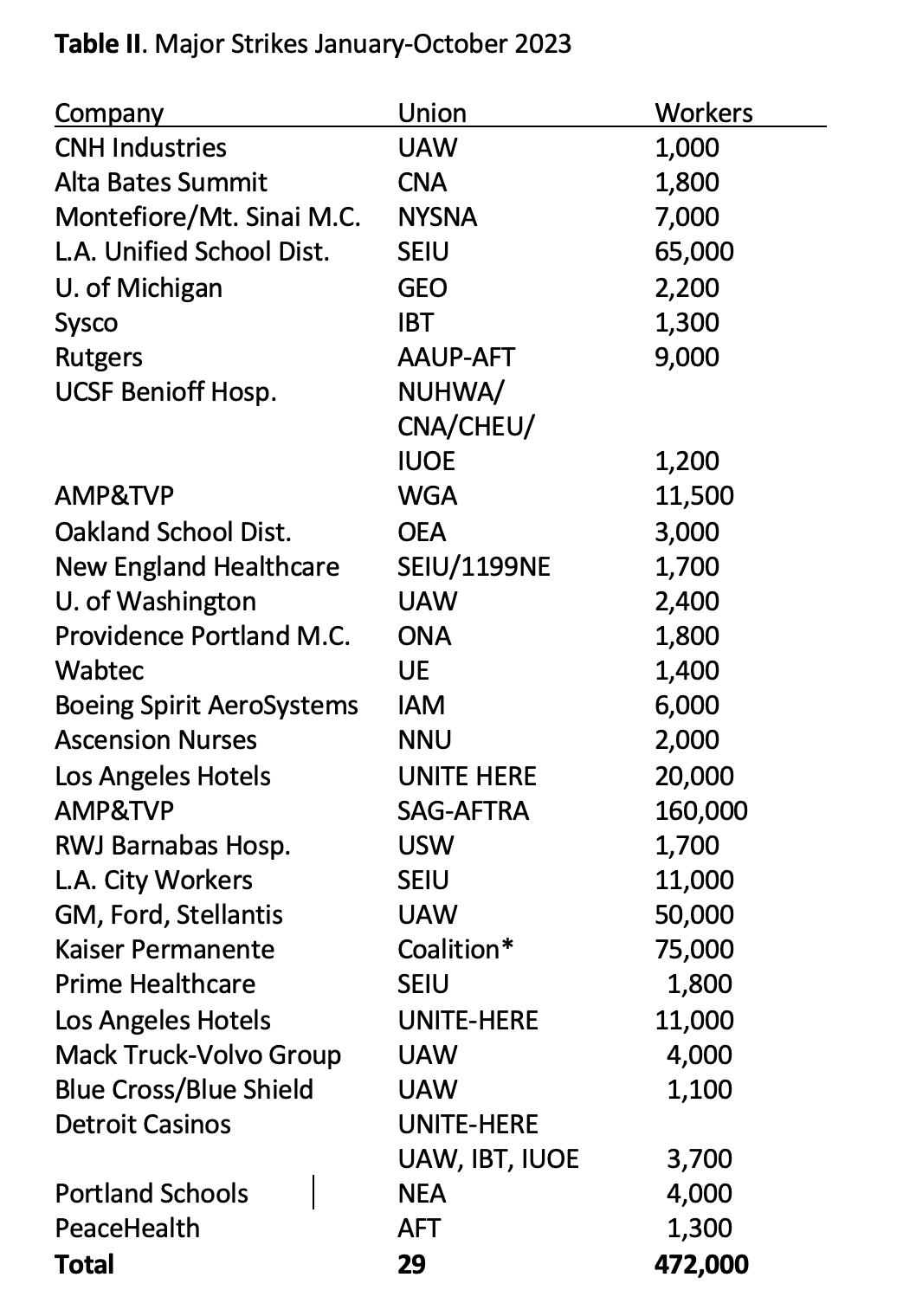

More workers in a broader variety of industries struck in 2023 than at any time since the teachers’ upsurge of 2018-19. Most of the estimated five hundred thousans strikers as of early November are accounted for by the twenty-nine “major” work stoppage involving one thousand or more workers mostly reported by the BLS, as Tables I and II below show. While workers in education and healthcare continued to dominate the numbers, important industrial strikes at Sysco, Wabtec, Boeing, Mack Truck, and the “Detroit Three” automakers added thousands.

The big newcomers—the Hollywood workers in the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA)—added 11,500 and 160,000 respectively bringing the numbers to a new post-pandemic high. The three-day strike of seventy-five thousand at Kaiser Permanente was the largest health care walkout to date and the union coalition representing the Kaiser workers threatened a longer walkout of eight days were an agreement not to be reached by November 1. Had the three hundred and forty thousand Teamsters struck UPS in August, the numbers would have far exceeded those of the teachers’ rebellions in each of its two years.

The total number of strikers in the first ten months of 2023 was still more than twice the two hundred and twenty-four thousand who walked off the job in 2022. By the end of September, the total number of days spent on “major” strikes, which were anything but what the BLS calls “days of idleness,” reached 10.9 million, already the largest number in twenty-three years with more to come. Altogether, over a third of the 1.6 million workers whose contracts expired in 2023 went on strike.

*Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions: 11 locals of SEIU, IFPTE, OPEIU

Furthermore, member activation and mobilization before actually striking became more widespread in 2023. Initiated with the blessing of the new Teamster leadership but carried out largely by the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), a highly crafted escalation of member activism in the form of parking lot meetings, breakfast gatherings, training sessions, and “practice picketing” helped back up the leadership’s strike threat. Members of the two Hollywood unions picked up on these tactics as did UAW members in preparation for their strikes at the Detroit (formerly “Big”) Three auto makers. So did thousands of the 53,000-member Culinary Worker’s’ Union (UNITE-HERE) in Las Vegas who “practice picketed” along “The Strip” on October 13, although they have not struck as of this writing.

The UAW’s strategy of targeted escalating strikes was also a first. Instead of the traditional pattern-setting strike at one of the three, the UAW decided to strike a limited number of facilities at each company, attempting to pit them against each other. While three assembly plants walked out initially, most of the first stage of the escalation closed down some thirty-eight GM and Stellantis parts distribution centers (PDC) out of about sixty belonging to all three companies. The PDCs supply dealers with spare parts and accessories and are highly profitable. Workers at these centers, however, are paid less than those at auto manufacturing plants.

The UAW vowed to end this two-tier set-up. The initial impact on industry sales as a whole was relatively small at least during the first two weeks. In September sales of new cars and trucks rose twenty-one percent for GM and eight percent for Ford. Stellantis saw a small one percent dip in sales. Then by September 29, workers at two more GM and Ford plants walked out, followed by Stellantis’ Sterling Heights Assembly bringing the number of strikers to about forty-six thousand in late October out of one hundred and forty-six thousand members at these companies. By then, GM had lost $800 million in profits and Ford $1.3 billion.

Before this, the threat of closing GM’s huge Arlington, Texas plant brought the union a significant victory when GM agreed to bring new EV battery plants under union contract. This was not only a big breakthrough for workers, but for a green transition in the auto industry as well. At the same time, encouraged by the union leadership and sometimes led by the reform caucus United All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) workers still on the job organized overtime bans, working “to the letter of the contract,” as UAWD chair Scott Houldieson put it on Democracy Now, and other tactics. At Ford’s Arlington, Texas plant before striking workers refused overtime and lunch time work despite threats by the Administration Cacucus local union officials that such actions could get people fired. In fact, with the contracts expired, workers have more room for actions up to and including overtime bans and even work stoppages. In acts of solidarity, Teamster carhaulers refused to deliver vehicles from struck plants to dealers.

Some of the biggest damage inflicted by the strikes, however, might be on the independent parts sector of the industry that also supplies the Detroit Three, other auto companies, and the parts aftermarket including the PDCs. According to Julie Fream, CEO of the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA), the independent parts industry association, forty percent of their member companies had laid off workers as of early October with more expected if the strikes continued. Since this would mean disruption in the parts supply chain generally, it was another source of pressure on the Detroit Three.

For decades, most US unions have avoided dealing seriously with technological changes or, indeed, many issues related to work and job security.

Although the UAW called its strategic actions “Stand-up Strikes,” in a reference to the historic “Sit Down Strikes” of the 1930s, the union did not target key engine or parts production sites that would have closed down most of the industry as they did at GM in Flint in 1936-37. Instead, the major goal appears to be hitting key sources of revenue, such as the highly profitable PDCs and the SUV producers, rather than affecting the whole production system directly. Of course, the union could always pull more key plants if bargaining remains sticky as it did at Ford’s Kentucky truck plant, GM’s highly profitable truck plant in Arlington, Texas, Stellantis’ equally profitable Sterling Heights Assembly Plant, and finally on October 28 at GM’s Springhill, TN plant, bringing the total number of strikers briefly to fifty thousand. Ford agreed on October 25; Stellantis and GM followed within days. In each case, the company agreed after the threat of an additional strike. The strategy of playing the automakers off one another appears to have worked.

The UAW won a 25 percent across the broad increase over four-and-a half years in the new contract, with eleven percent in the first year. This is far less than the forty percent the union initially demanded, but the union is quick to point out that it is more than four times the gains in the 2019 contract and exceeds in value all the increases of the past twenty-two years. The strikes also won back the COLA after it had been surrendered during the 2008-2010 recession. This is expected to raise the overall wage increase to thirty-three percent over the life of the contract. Temporary workers will become full-time employees over nine months and will reach top pay in three years rather than eight. Along with the elimination of wage tiers, this means life-changing wage gains for some workers.

The union concedes, however, that it was unable to win back the defined benefit pensions also given-up during the recession. In addition, despite the “pledge” by Ford to bring a number of EV battery plants under the master agreement, a major gain for the union, not all EV battery plants will “automatically” become union. Three other Ford plants “will have to organize the old-fashioned way,” Labor Notes reported. GM and Stelantis agreed to bring new EV battery plants under the master agreement.

In the first step of the UAW ratification process, all three national councils approved the agreement unanimously. The next step was local meetings to discuss the agreements and a vote by the members. As of mid-November, with voting still incomplete, Ford workers had ratified their agreement by sixty-five to thirty-five percent with thirty-two or fifty-four locations reporting, GM a fairly narrow fifty-six to forty-four percent with just half of locations reported, and Stellantis an overwhelming eighty-two to eighteen percent with the majority of locals yet to report. While the differences in the three companies is hard to explain, aside from that at GM, the votes were somewhat closer than expected indicating significant dissent.

A resolution passed at a membership meeting of UAWD on November 1, before the votes were available, stated “UAWD recognizes and celebrates the record gains made in this agreement.” They also note, however, that “there is not consensus within our own caucus let alone among UAW members more broadly on the current Tentative Agreements.” One of the biggest criticisms was the failure to win back defined-benefit pensions for all. The caucus did not advocate a yes or no vote but pledged to educate members on the contents of the agreements. Despite some shortcomings, the Detroit Three contracts represent a substantial reversal of four decades of concessions and retreats.1For a concise account of the process of the UPS and Detroit Three strikes and agreements see Dianne Feeley, “Strategies for Union Victories,” Against The Current #227 (November-December), 6-9; Dan DiMaggio, “Big 3 Buckled as Stand-Up Strikes Spread,” Labor Notes October 31, 2023, https://www.labornotes.org/2023/20/big-3-buckled-stand-strike-spread.

Not everything this year was a clear advance for the UAW. Mostly out of sight of the mainstream media, on October 9, 4,000 UAW members struck five plants at the Volvo-Group’s Mack Truck operations after rejecting a tentative agreement by seventy-three percent on the grounds that it did not live up to the standards being set in the Detroit Three negotiations. One veteran Mack worker complained of the union leaders “they are just pushing this through, so they don’t have to deal with us while the Big Three are negotiating.” The rejected tentative agreement had included a nineteen-percent increase over five years, below inflation and not half of what was initially on the table with the Detroit companies. Furthermore, it failed to eliminate a two-tier set-up. In what was perhaps a face-saving move, UAW president Shawn Fain told the press, “I’m inspired to see UAW members at Mack holding out for a better deal, and ready to stand up and walk off the job to win it.”

Following the Detroit Three settlements, over nine thousand more workers walked out as of early November. These included two “major” strikes: four thousand NEA members in Portland Oregon schools and thirteen hundred nurses at PeaceHealth in Vancouver, Washington. In addition, seven hundred CWA technical workers at the New York Times; seven hundred SEIU healthcare workers at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Burbank, California; and four hundred UNITE-HERE members at the Phoenix airport also hit the bricks among others. This brought the total as of early November to approximately five hundred thousand. No doubt there would be more strikes before the year is out.

Aside from the obvious demand for increased wages to help make up for the losses in real income workers have experienced for years, many of this year’s strikers shared common concerns and goals about the impact of major technological changes impacting the nature and prospects for work where they are employed. For auto workers it is the shift to electric vehicles; for healthcare workers staffing and the threat of Artificial Intelligence (AI); surveillance for UPS drivers; for screen writers and actors it is streaming and AI; for manufacturing workers like those at Wabtech or Boeing it was both new technology and changes in the industries they produce for.

For decades, most US unions have avoided dealing seriously with technological changes or, indeed, many issues related to work and job security. The major turning point for this surrender was Walter Reuther’s famous 1950 “Treaty of Detroit” between the UAW and the then “Big Three” that granted sole management control over investments and production in exchange for significant economic and benefit gains. The fact that a number of unions are attempting to grapple with issues considered “management prerogatives” at a time when change has accelerated is a positive if as yet uneven development. In particular, some gains were made in the WGA contract protecting workers against loss of income and work due to streaming and AI. While even in the midst of its strike, GM and Stellantis agreed to put new EV battery plants, mostly in the South, under UAW contract.

While it would be an exaggeration to say that all the current polls showing large majority support for unions and strikers reflects as strong or pervasive a consciousness as that of the post-war period, they do suggest a significant change in the feelings and sentiments of most working-class people.

Just how effective contract language and enforcement is, or how much of this actually constrains the effects of technology and/or industry reorganization, won’t be clear for some time. Nevertheless, workers taking on management prerogatives and “nonmandatory” bargaining issues through their organized power, not some fake “employee participation” scheme, is a step toward increased workers’ power and the invasion of the “tyranny of capital.”

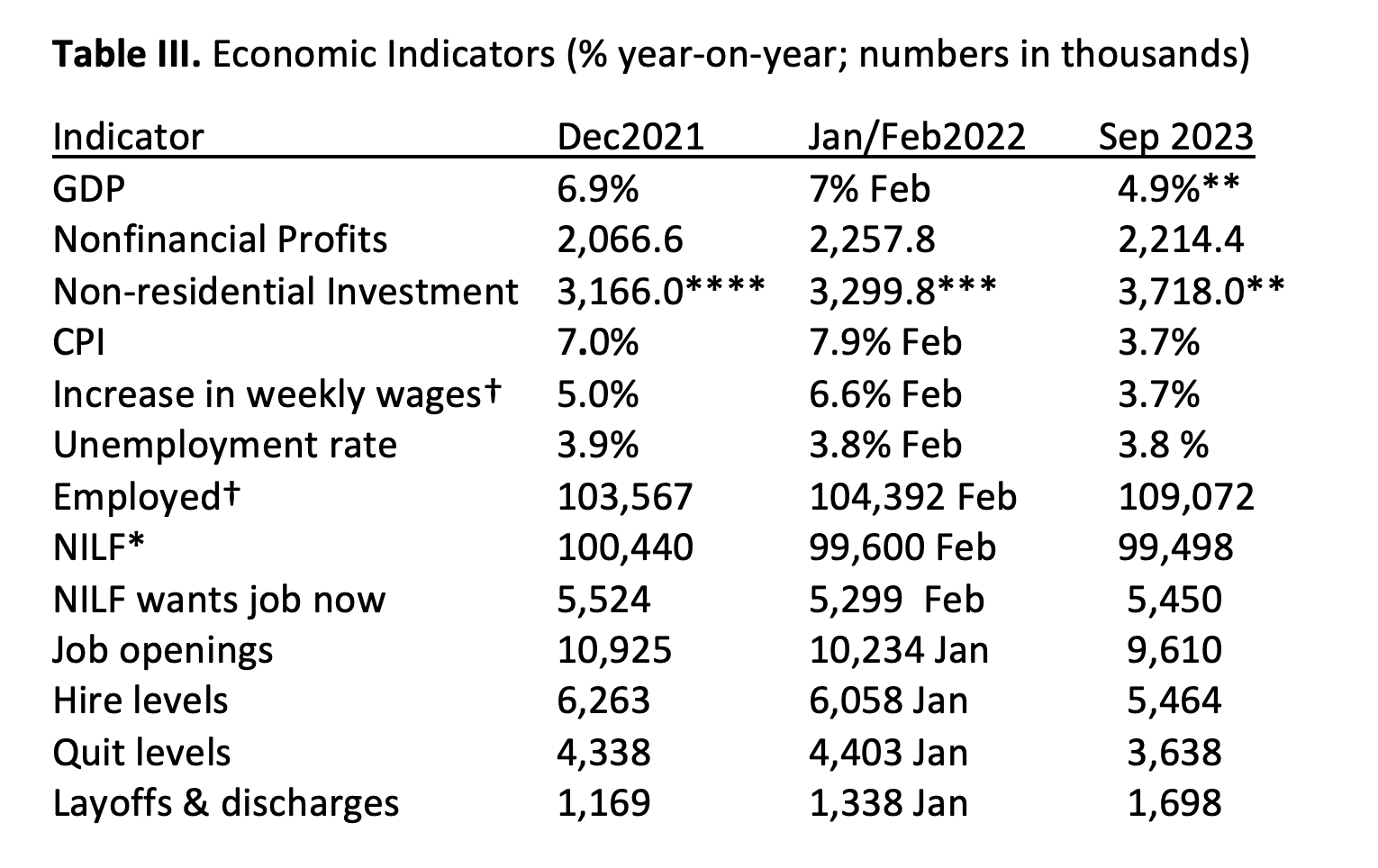

Progress on wages, of course, is easier to measure. By that metric, average annual wage increase has been rising due to inflation-driven worker actions and the tight labor markets of the last four years. Bloomberg reports that first year wage increases in new union contracts have risen from 3.1 percent in 2020 to 3.7 percent in 2021, 5.7 in 2022 and 7 percent in early 2023. This year is the first time in recent years when first year increases were higher than inflation. Second- and third-year increases, however, are typically more in the four to five percent range. So, while workers are making gains, most have not made up for past lost real wages.

Some workers got higher than average increases. The Teamster settlement at UPS saw part-time workers get a large first year increase as much as twenty-six percent over the old contract, though the union failed to eliminate the two-tier set-up between part-time and fulltime workers and actually accepted a new lower tier for new hires. The Service Trade Council, a coalition of unions representing 32,000 workers at Disney World won a thirty-seven percent wage increase over five years, an average of 7.4 percent a year on top of their old $15.00 an hour wage after an earlier offer was rejected by ninety-six percent. Kaiser Permanente’s seventy-five thousand workers a minimum of $25 an hour and an increase of twenty-one percent over four years.

Nevertheless, by August 2023, despite an increase from May 2021 through July 2022 and a drop in the CPI in 2023, real average hourly wages of production and nonsupervisory workers at $9.63 as of September 2023 remained stuck at just twenty-five cents above its half-century-ago February 1973 level of $9.38. Clearly decades of concessions have permanently eroded working class living standards to a point that will be hard to make up through conventional collective bargaining.

Business Unionism, Strike Waves, and What Lies Ahead

Because US unions bargain separately, have different expiration dates and contract durations, and typically include “no strike” clauses that prevent walkouts during the life of the contract, the possibility of a simple escalating strike “wave” is remote. For one thing the number of workers covered by contract expirations differs from year to year. Because striking during the life of a contract is illegal in most cases, work stoppages usually occur when the contract expires, so the likelihood of increased walkouts is affected by the number of official expirations. To make matters worse, more unions have given management longer contract durations. So, while 2023 saw some 1.6 million workers covered by contracts that expired, the number for 2024 will be significantly smaller, as a scroll down the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Services’ list of contract expiration notices indicates. All of this is the heritage of bureaucratic business unionism.

To break through this limitation would require that unions demand and win the elimination of “no strike” and “management’s rights” clauses, as well as winning “re-opener” clauses to allow for negotiations on changes during the life of the contract. The only union to attempt to strike out its “no strike” clause this year was the United Electrical Workers (UE) at Wabtech. Despite a long strike, they failed to win this difficult demand. Had other major unions such as the Teamsters and UAW adopted a similar demand things might have been different, but that was never very likely. The UAW did win the right to strike over plant closures, and at Stellantis outsourcing as well, but not other issues. Similarly, pushing for shorter contract duration could help bring expirations closer. While this may sound far-fetched, it was not that distant from the practice of the major CIO unions as they emerged from World War II despite the conservatism of the CIO leaders and the deep political divisions among them in a brief period before business unionism had become the universal norm.

In the years just after the war ended, CIO union leaders and activists spoke of bargaining “rounds.” The rounds were seen as a time when the major industrial unions sought to terminate existing agreement and negotiate new contracts more or less at the same time. The crucial unions were those in coal mining, auto, electrical goods, steel, packinghouse, tires, and maritime. The 1945-46 round was not coordinated by the CIO, its leaders fought one another, some joined late in the process, was opposed by the Truman administration, and bitterly resisted by the employers. Nonetheless, the idea was that if the half dozen or so largest CIO unions could win a common wage increase, this would set a pattern for all industrial unions and workers.

Despite the problems, this strike wave began in September 1945 when forty-three thousand oil workers, two hundred thousand coal miners, and forty thousand lumber workers walked off their jobs with more soon to follow in October. But the big escalation came at General Motors in November as two hundred and twenty-five thousand UAW members struck the auto giant. In January 1946, as eight hundred thousand steelworkers, two hundred thousand UE members, and over two hundred thousand meatpacking workers joined the escalating upsurge so that some two million workers were on strike. U.S. Steel gave in in February, while General Motors didn’t settle until March. Altogether in 1945, 3.5 million union workers were on strike and in 1946 it reached 4.6 million.

This latter figure includes the mostly AFL union workers who launched city-wide general strikes in solidarity with local struggles in six mid-sized industrial cities across the country in 1946.2George Lipsitz, Rainbow at Midnight: Labor and Culture in the 1940s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 120-154. This really was a strike wave. In the aftermath, however, capital struck back with Taft-Hartley, labor fragmented as the CIO expelled the Communist-led unions, bureaucratic business unionism tightened its grip, contract durations became longer, the “rounds” were replaced with individual industry pattern or national agreements in the 1950s, and even that was surrendered in the 1980s.

The reasons for the 1945-46 strike wave were many, including pent-up frustrations from the war period sacrifices, a determination to establish decent living standards in the post-war era, the big profits the major companies were raking in during and after the war, the need of leaders to deliver to an expectant and demanding membership, and so on. Art Preis’s account of this in Labor’s Giant Step, which I have relied on heavily but not exclusively here, makes clear that much of this was possible because the ranks of the unions pushed for strike action to make up for loses during the war. As Preis described the consciousness of workers at that time:

A tremendous feeling of labor unity pervaded the organized workers during this period that tended to break down in action the divisions set-up by bureaucratic, factional, and craft interests.

While it would be an exaggeration to say that all the current polls showing large majority support for unions and strikers reflects as strong or pervasive a consciousness as that of the post-war period, they do suggest a significant change in the feelings and sentiments of most working-class people.

Working class power and internal class formation is being built piece-by-piece, sector-by-sector, and increasingly across these and other lines of division.

Although a repeat of the 1945-46 strike wave is not really in the cards in the foreseeable future, following their success at the Detroit Three, the UAW not only brought the expiration dates of all three new contracts to April 30, but President Shawn Fain invited other unions to coordinate their contract expirations over the next few years to coincide with the UAW’s May 1 expiration. He suggested that the shorter work week, which the UAW raised but did not attempt to win this year beyond a week’s family leave and the Juneteenth as a paid holiday, could be part of a coordinated strike movement. “May Day was born out of the intense struggle by workers in the United States to win an eight-hour day,” he declared. “That’s a struggle that is just as relevant today as it was in 1889.” 3The May 1 general strike for the eight-hour day was in 1886, not 1889.

Looking at the near-term future, while I don’t have all the figures yet, the 2024 bargaining “calendar” looks significantly lighter than this year’s. There are, however, some big contracts expiring, some as soon as New Year’s Eve. At midnight SEIU contracts mainly with janitorial and building service employers covering about fifty-seven thousand workers in various cities expire. More SEIU contracts covering about six thousand security guards expire in February and that covering over fifteen hundred healthcare workers at the Mayo Clinic in March. The 1199 SEIU contract with ninety New York hospitals covering seventy-eight thousand workers which would have expired in September 2024, was reopened and ratified in March 2023 in the wake of the NYSNA victory at two major New York Hospitals in January. Other large bargaining units with expiring contracts next year include: thirteen hundred nurses in the NYSNA at Staten Island University Hospital in January; thirty-two thousand UFCW members at Meijer Great Lakes grocery stores in February; and twenty-five thousand Safeway employees in October. Perhaps most tantalizing of all, the tentative agreement and strike ban imposed on one hundred and fifteen thousand railroad workers in 2022 expires in 2024 just before the election.

Tight Labor Markets, Deteriorating Conditions and Consciousness

Strike movements, of course, are also affected by the condition of the economy. For the past three years, tight labor markets have encouraged workers to risk a strike. The sharp “Covid” recession of 2020 stalled that, but an upward trend resumed the following year as Table I shows. More generally, as Table III indicates, while the employment of production and nonsupervisory workers has grown significantly, some of the indicators of a tight labor market, such as job openings, hires, and quits have recently softened while lay-offs are up somewhat. GDP has slowed down, though the Third Quarter figures of a 4.9 percent growth is up from a low of 2.1 percent in the second Quarter of 2023. The mass of profits actually fell in the second quarter of 2023, while investment increased, though only slightly above the previous quarter and in real terms fell slightly. Together with slower growth this suggests a falling profit rate ahead and a possible recession next year. In other words, the conditions that helped spawn the big increase in strikers may be receding.

*NILF = Not In Labor Force

** Q3

***Q1

****Q4

†Production and nonsupervisory workers

The ups and downs of the economy and even the levels of unemployment, however, are not absolute determinates of workplace struggle. The 1945-46 strike wave took place as war production nosedived with a million laid-off even before the war ended, real GDP fell by fourteen percent from 1944 through 1946, and the number of unemployed workers soared from 670,000 in 1944 to 2,270,000 by 1946. Yet, the need to set new standards for the post-war period, the solidarity consciousness that Preis described, and an active membership kept militancy alive and the strike wave escalating. A look at the Great Depression years from 1933 through 1937 shows that while ups and downs of employment did impact strike activity for a time, unemployment never fell below ten percent over this period and yet did not break the growing consciousness and militancy as more and more workers gained experience in struggle and the “militant minority” of rank-and-file leaders grew and the strike wave reached a new high in 1937 when nearly two million workers struck.

The return of strike activity that began with the teachers in 2018 has seen a lot of rank-and-file initiative and even organization. As Jane Slaughter recently argued in Labor Notes, this year’s UAW strikes were possible “because four years ago a small group of activists founded a new reform caucus.” The United All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) helped bring new leadership to the UAW and then took a lesson from the Teamsters for a Democratic Union mobilizations at UPS and applied them to the auto barons even before striking. In November, UAW president Shawn Fain, in turn, will speak at the TDU convention. Rank-and-file initiatives have been important from hospitals, schools, universities, Teamsters, UAW, the United Food and Commercial Workers, and workers at Amazon among others.

Socialists have often played a role in these new movements, much as they did the past, helping to form today’s as yet small “militant minority.” While a deep recession would certainly diminish strike activity and new organizing, it is this process of internal class formation along with the consciousness implied by class-wide support for unions and strikes in so far as they become organized that can help keep up or reboot the momentum even if the economy slows down and unemployment rises somewhat.

Picket Lines and Politics

Few strikes got media attention like the “unprecedented” appearance of President Joe Biden on the UAW picket line at a General Motors plant in Belleville, Michigan. The “unprecedented” part was, of course, that the visitor was the POTUS. Biden, however, was not new to the political uses of picket lines that coincide with crucial elections. In 2019, facing challenges from Bernie Sanders and possibly Elizabeth Warren as the presidential primaries took off, Biden visited a UAW picket line in Kansas City during that year’s GM strike. He was soon followed by Warren. This year’s parade of picketing politicians has grown beyond the usual Bernie, AOC visits to include not only the president, but also New York Governor Kathy Hochul and Senator John Fetterman.

In explaining British Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s rather lame attempt to win back working-class voters by using the phrase “working people” over and over, Guardian columnist Aditya Chakrabortty aptly called the practice “class politics as marketing strategy.” No doubt Biden and/or his advisers had seen the polls showing rising support for unions and strikes. And like good market research experts they responded in kind. Biden needed these blue-collar votes to carry those midwestern swing states if he is to take the Electoral College in 2024 and this “market” looked good.

Some will say this is too cynical an analysis. Just because he was on his way to one of those California big bucks fund raisers with a rather different class of people than in Michigan or that he has met with GM CEO Mary Barra far more frequently at the White House to discuss the future of the auto industry, and that his polling is catastrophic doesn’t mean he’s just playing politics. Doesn’t it? While many were no doubt grateful for the executive gesture, others on the UAW picket lines suspected it might just be “politics” after all, at least according to interviews by the Huffington Post.

Biden had good reason to go seeking blue collar votes, because while polls were showing majority support for those UAW strikers, other polls indicated that most American voters have little faith in Biden as president, politicians in general, and the Democratic Party in particular. A September Washington Post/ABC poll put Biden’s approval rating at thirty-seven percent and his handling the economy at thirty percent. An annual Pew Center survey on political attitudes conducted in June and July showed that the Democratic Party’s overall approval rating had dropped from sixty percent around 1999-2000 to the mid-forties from 2008 through 2017, and then to thirty-seven percent in 2023. Its “disapproval” rating shot up to sixty percent. Clearly, Biden and his party are in trouble. The contrast between the majority who see unions as a means of defending and advancing living standards and their opinions of “politics” could hardly be greater.

Turning Point?

After years of givebacks, retreats, and falling real wages, the strikes that began in 2018 and reached new highs this year have for the most part brought gains instead of concessions. However modestly, they have reversed the trend. Looking at wage increases in early 2023 even before they reached their highest average, Bloomberg analyst Robert Combs (March 21, 2023) declared “Union Workers Haven’t Seen Raises Like This in Decades.” While for most, these gains are not enough to erase those same decades of concessions and real wage cuts, the escalation of wage increases is largely a result of workers taking advantage of improved economic conditions and using their power once again.

Furthermore, over the past few years, issues involving the nature and changes in production and work have become central to bargaining not only in healthcare and education, but from Hollywood studios, to UPS vans, to Michigan auto plants, and to those yet to be built. Whether the outcomes of this are enough to meet the big changes in production, distribution, and work that capital is seeking is, as usual, debatable, but the direction is hopeful for a change.

A key factor that has made the strikes of this year effective is the high level of rank-and-file activism both before and during many of these struggles. Just as Art Preis described the crucial role of pressure from the ranks in the post-WWII strike wave, so grassroots union member demands and actions, in some cases in the form of organized rank-and-file caucuses, have been central to the new era of worker action and strikes. This is most obvious where reform movements have either taken over or supplied direct pressure from below. Union democracy, however, plays a role in militancy even when the challengers don’t win. For example, while the negotiations and the long strike by SAG-AFTRA have been led mainly by the “old guard” Unite for Strength leadership faction that has run the union since 2016, pressure from the reputedly more militant Membership First opposition caucus—that came close to winning the presidency and did take the secretary-treasurer’s position in 2021—no doubt helped keep the leaders on track.

At the same time, as measured by Gallup polls over the years, the levels of support for unions today are actually somewhat higher on average than those in the 1940s during the post-war strike wave and the high point of the rank-and-file rebellion from the mid-1960s through the early-1970s. As simple demographics tell us, the majority of those answering these surveys are working-class. Thus, the recent polls that show growing support for unions and strikers are also an indication of an increase in the kind of solidarity consciousness that drove the post-WWII strike wave. Though this time, as explained earlier, it is trapped in the rhythms of business unionism.

The implications of all of this for socialists should be clear. Working class power and internal class formation is being built piece-by-piece, sector-by-sector, and increasingly across these and other lines of division. Insofar as this process continues, it will alter the possibilities for greater organization and political consciousness across union and industry lines by workers themselves. In that sense, this could be a turning point in the class struggle. For those us for whom workers’ democracy is the foundation of socialism, the fight for greater workers’ power and democracy in the union, on-the-job, and in society is a step toward that goal, a rehearsal in which we prepare for power no matter how far off that goal may seem.