Spectre is pleased to be publishing Kim Moody’s overview of the conditions and potentialities of workplace struggle in the US today. We hope this will launch a “labor beat” on our website—reports and analyses of workplace struggles in the US and internationally. Please submit your analysis of the state of the labor movement to us at inbox@spectrejournal.com, including “labor beat” in the subject line.

Amidst capitalism’s multiple crises—from slow growth to climate change to pandemic to supply chain breakdown—an unusually worker-friendly economic conjuncture has emerged, one unlike any seen for decades. Massive numbers of workers quitting their jobs, soaring job openings, relatively low unemployment, rising inflation, political paralysis, and an unusually heavy schedule of union contract expirations in 2022 have converged to create the most favorable conditions for aggressive worker actions, strikes, and economic gains since the 1970s. It is almost certainly an economic convergence that cannot last given capitalism’s underlying problems and contradictions. It is, nevertheless, one that can propel the uptick in worker actions that began in 2021 to new heights if workers and their unions take advantage of conditions that in a year or two might fade into the system’s more normal contemporary state of stagnation, joblessness, relentless speed-up, and falling living standards. For socialists, it presents an opportunity to participate in and help escalate the development of on-the-ground worker organization in and outside of today’s unions.

COVID-19: US labor & capital in sickness and wealth

Everyone suffers from the pandemic, right? Not exactly. A study of 3,220 US counties conducted in 2020 discovered “that income inequality within US counties was associated with more cases and deaths due to COVD-19 in the summer of 2020.”1Annabel X. Tan; Jessica A. Hinman; Abdel Magid, PhD; Lorene M. Nelson, PhD, MS; and Michelle C. Odden, PhD, “Association Between Income Inequality and County-Level COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US,” May 3, 2021, JAMA Network Open; 2021, 4(5):e218799.doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8799. Not only were America’s richest healthier on average, but they got even wealthier as the disease spread. The US capitalist class’s billionaire cohort grew from 614 individuals (or households) in March 2020 to 745 in October 2021. Their net worth soared from $3 trillion to $5 trillion over that period. This combined 2021 wealth of these 745 home-grown economic oligarchs overshadows the $3 trillion in wealth held by the bottom 50 percent of US households.2Institute for Policy Studies, “U.S. Billionaire Wealth Surged by 70 Percent, or $2.1 Trillion, During Pandemic. They’re Now Worth a Combined $5 Trillion, “ Institute for Policy Studies, October 18, 20201, https://ips-dc.org/u-s-billionaire-wealth-surges-by-70-percent-or-2-1-trillion-during-pandemic-they’re-now-worth-a-combned-5-trillion.

Of course, there is instability among the wealthy, and some of these billionaires took a bit of a hit on their paper wealth in January when stock prices fell as interest rates rose and people sold off their tech stocks. The biggest players, however, seldom lose out for long. As Business Insider put it,

Bur not all tech companies are equal. Analysts expect stocks such as Apple, Amazon and Google to fare much better in 2022 than unprofitable tech companies, because, simply put, they make tons of money.

It wasn’t just the elite of capital that prospered, however. Capital as a whole made out like the bandits they are. Domestic nonfinancial corporate profits jumped by 22 percent from the Third Quarter of 2020 to the Third Quarter 2021 to an all-time high of $1.9 trillion.3Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 6.16D. Corporate Profits by Industry,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, January 27, 2022, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey. The big companies in the Standard & Poor 500 saw profit margins soar to 12 percent in December 2021, “a level of profitability never before seen,” according to Bloomberg. This compared to 9.5 percent in April 2021 and 9.5 percent in 2007 just before the great Recession.4John Authers, “What Inflation in 2022 Will Teach Us About Capitalism,” Bloomber.com, December 27, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-12-27/what-inflation-in-2022-will-teach-us-about-capitalism. These are the kinds of gains that capital would not be likely to give up without a fight.

Things were not so good for working-class people. Median household income fell by 3.2 percent for family households and 3.1 for nonfamily households from 2019 to 2020, while wage increases due to labor shortages during the pandemic were more than wiped out by inflation in 2021. In 2020, as the pandemic swept the US, 31.2 million persons under 65 had no health insurance, while over three million people joined the poverty rolls that year.5Emily A. Shrider, et al,. Income and Poverty in the United States:2020, September 2021, Washington DC: U.S Census Bureau, 15; All employment, wage, inflation, and union membership figures in this essay are from BLS sources unless otherwise cited and won’t be cited individually. In 2020 millions lost their jobs in the deepest downturn in years, while in 2021 millions found work again, but at lower pay—sometimes in employer “fire and rehire” schemes where workers were offered their old jobs back at lower wages. Millions more lost their pandemic unemployment benefits in September 2021 again heading for lower paid work. For example: goods producing jobs for production and nonsupervisory workers paying $1,110 a week increased by just 477,000 from December 2020 to December 2021, but service jobs paying $880 a week increased by 4.5 million over that time, almost half of them in warehousing at an average of about $860 a week. To make matters worse, unions lost 241,000 more members in 2021. These were the kinds of setbacks, conditions, and losses that could not be transcended without a fight.

Shaping a new conjuncture: Hurry-up and wait

For decades capital has been attempting to produce more with less and do it faster. In search of bigger shares in the profit pie, competing businesses have fought to increase their rate of exploitation with lean production methods, streamlined “just-in-time” supply chains, warehouses turned from places of storage to those of movement, employees misclassified as contractors, wages held to a minimum, the pace and content of work intensified, and the movement of goods from factory to market accelerated. The pandemic brought this to a screeching halt in the spring of 2020 as factories closed at home and abroad and lockdowns sent workers home or to the hospital. Then, the same virus hit the accelerator as “locked-down” people ordered more goods from home and companies scrambled for more workers to make and move those goods. World merchandise trade and US imports soared to new highs.6World Trade Organization, “Third Quarter 2021 Merchandise Trade Value,” WTO OMC, December 17, 2021, https://www.WTO.org/english/res_e/statis_e/daily_update_e/merch_latest.pdf.

Labor shortages long in the making due to low wages and/or bad conditions in trucking and warehousing along with reductions in the workforce and less profitable routes by the big seven freight rail carriers practicing lean-style “precision scheduled railroading” all led to clogged ports and warehouses, overloaded “intermodal” facilities, “slow steaming” container ships, parts shortages, and employers suddenly desperate to hire more workers. Ships were stranded outside major ports, long lines of trucks waited to be unloaded, and warehouses became jammed up with things that could no longer be stored or moved “just-in-time.”7Peter S. Goodman, “How the Supply Chain Broke, and Why It Won’t Be Fixed Anytime Soon,” New York Times, October 22, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/22/business/shortages-suppl-chain.html; David Dayen and Rakeen Mabud, “How We Broke the Supply Chain,”, American Prospect, January 31,2022, https://prospect.org/economy/how-we-broke-the-supply-chain-intro/?utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium==email&utm_content=Watn+to+know+why+inflation+is_rising%3F&utm_campaign=Supply+Chain+Launch; Transport Topics, “Driver Shortage Defines Trucking for 2021,” Transport Topics, December 17, 2021, https://www.ttnews.com/articles/driver-shortage-defines-trucking-2021; Augusta Saraiva and Brendan Murray, “”Every Step of the Global Supply Chain Is Going Wrong-All at Once, “ Bloomberg, November 23, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-congestion-at-americas-busiest-port-strains-global-supply-chain; Abha Bhattarai, “Wareouse jobs-recently thought of as jobs odf the future-are suddenly jobs few workers want,” Washington Post, October 11, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/10/11/qwarehouse-jobs-holidays-seasonal-hiring/; Jacob Atkins, “Goodbye, supply chain crisis of 2021. Hello, supply chain crisis of 2022,” Global Trade Review, December 14, 2021, https://www.gtreview.com/global/goodbye-supply-chain-crisis-of-2021-hello-supply-chain-crisis-of-2022; S. L. Fuller, “JB hunt invests in intermodal as rail congestion hampers operations,” SUPPLYCHAINDIVE, January 27, 2022, https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/intermodal-trucking-rail-jb-hunt-schneider/61764/. On the one hand, we got the “great supply chain crisis of 2021”, on the other, the tightest labor market since the 1970s.

Desperate employers were suddenly raising wages in order to attract workers, but soaring prices destroyed those gains faster than bosses could or were willing to improve the offer.

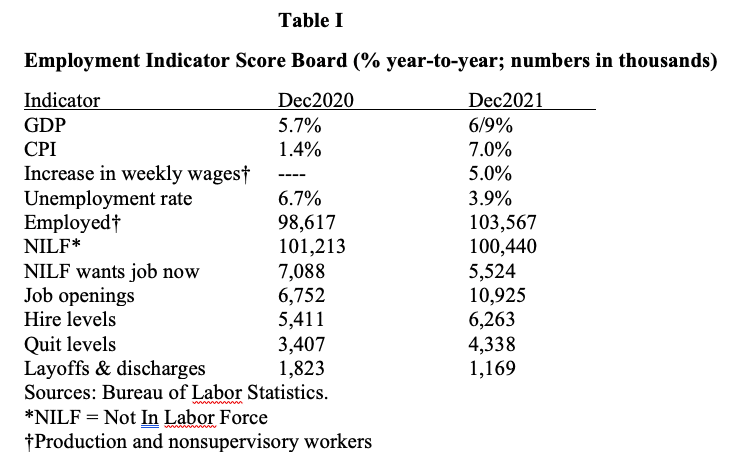

For the first time in half a century the “reserve army of labor”, those unemployed, out of the workforce but willing to work and those in peripheral employment began to visibly shrink. It is this “reserve army” of available workers that helps capital restrain wages, provide potential strike breakers, and discourage employed workers from quitting, demanding more, and striking. Table I shows that by every conceivable measure in 2021 this reserve of people traditionally hungry enough to work for less or replace strikers was getting smaller and desperate workers more scarce—though never, of course, wholly absent. Employment and job openings were up, layoffs down, so were those “not-in-the-labor-force” (NILF) who wanted work. Workers were quitting low-paid jobs in hopes of better opportunities, even in those industries with relatively high proportions of Black and/or Latinx workers who have higher unemployment rates such as “leisure and hospitality.” Desperate employers were suddenly raising wages in order to attract workers, but soaring prices destroyed those gains faster than bosses could or were willing to improve the offer.

The inflation of 2021 wasn’t driven by those wage increases which were playing catch-up with rising prices, nor was it the kind of consumer-driven inflation that mainstream economists often blame and that the Federal Reserve Bank tries to dampen by raising interest rates. The driving forces behind the inflation of 2021 and 2022 were in the production and transportation “bottlenecks” caused by the supply chain crisis of 2021 and labor shortages, which were expected to last into and beyond 2022. The disrupted movement of goods was costing more. While consumer prices rose by 7 percent from December 2020 to December 2021, the cost to producers of freight trucking for intermediate goods moving from factory to factory and those for finished products from factory to market both rose by 17.7 percent. This compared to 2.3 percent for each from December 2019 to December 2020. Prices for intermediate materials for manufacturing were up 38 percent in 2021. Scanning the field of wreckage for weak points from which to leverage outsized profits in 2022, financial predator Black Rock argues, “We’ve entered an era where supply constraints are the driving force of inflation, rather than excess demand.” It was not high growth rates that were driving prices up since, despite big profits, real GDP scarcely grew at all in 2021. As Black Rock put it, it wasn’t the “economic engine” that drove inflation, but “the engine misfiring.”8Black Rock Investment Institute, “A world shaped by supply,” Macro and market perspectives, January 2022, 1, 3. And misfiring in terms of broken supply chains, unavailable parts, and discontented workers will continue for some time.

Payback time: 2022

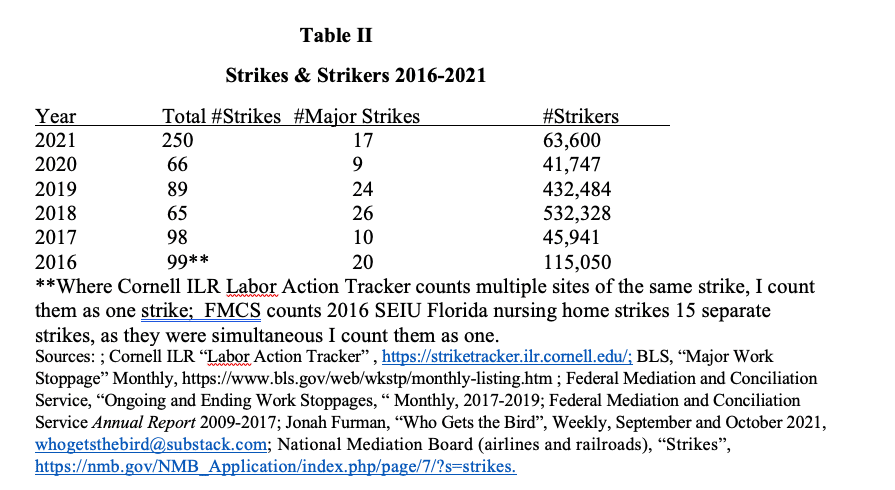

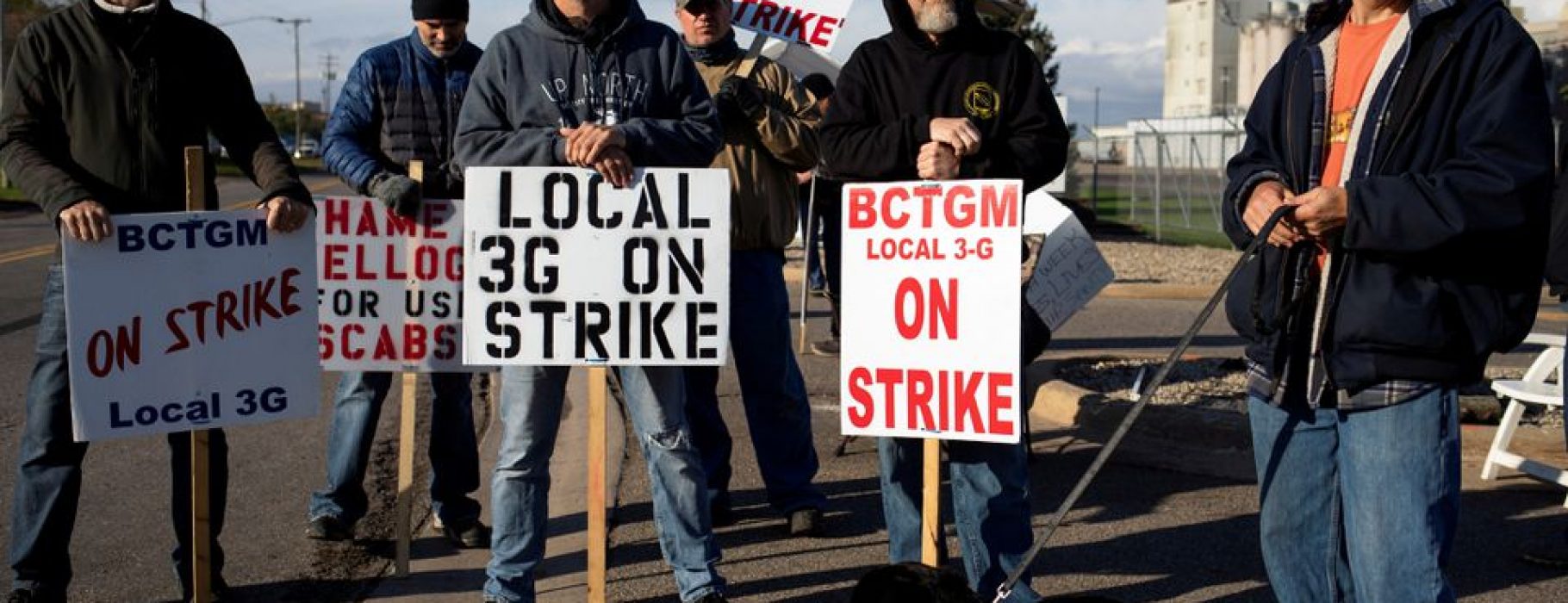

Taken together, the combination of a tight labor market and persistent inflation is a classic recipe for increased labor militancy and the potential to begin to reverse the setbacks of the last forty years. While it was hardly a “strike wave”, as Table II shows 2021 saw some 250 strikes—more than in any year since before the Great Recession of 2008. Some were big like those at John Deere, Volvo, or Mercy Hospital in Buffalo. Many, however, were in small bargaining units or even outside of union representation. Overall, the numbers of strikers didn’t come close to those of the teachers’ strike of 2018 and 2019. Nevertheless, the increased frequency of direct action pointed toward a willingness to fight by workers who were called “essential” but treated as disposable—workers who went from “heroes to zeros” in less than a year.

These first signs of a new militancy were not only for better pay, safer workplaces, and better conditions, but in a real sense beginning the Herculean task of undoing four decades of contract concessions, falling real wages, two-tier wage schemes, lost benefits, digitalized speed-up, and ever more invasive surveillance. From strike votes to contract rejections, the evidence is that the push for strikes has been coming from the ranks, more and more of whom have overcome the fears and insecurities of yesterday enough to begin to take on this demanding task. The uptick of 2021 can become the upsurge of 2022 and beyond if—and there are some big ifs.

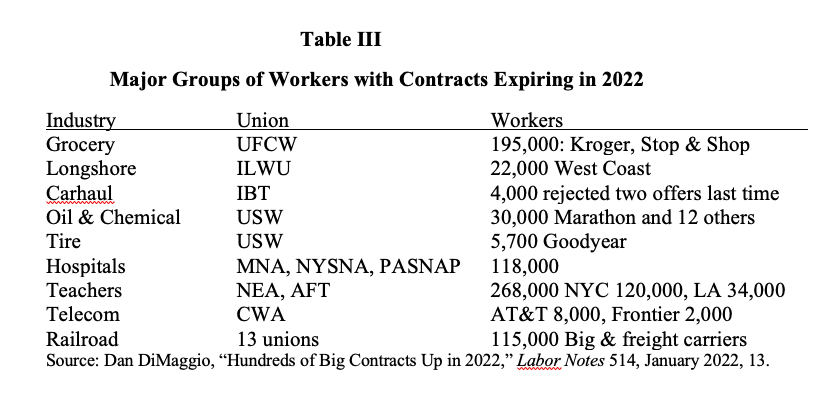

The normally routine annual collective bargaining calendar that has for a long time been the scene of give-backs and stagnant or falling real wages, nevertheless, sets the stage for a class struggle drama in 2022. This year will see an unusually heavy bargaining schedule as nearly two hundred contracts covering 1,000 or more workers representing 1.3 million union members expire between the end of 2021 and the end of 2022.9Dan DiMaggio, “Hundreds of Big Contracts Up in 2022,” Labor Notes 514, January 2022, 13. That’s compared to 160 such large contracts last year. Table III lists the major groups of workers and their unions facing negotiations this year. Many are in sectors where workers have already appeared more strike-prone than average including those in grocery, healthcare, education, and telecommunications. In addition, hundreds of thousands of other workers are covered by contracts expiring in smaller bargaining units. There are also organizing efforts among workers who aren’t supposed to be able to unionize at high turnover firms like Amazon and Starbucks, by “independent contractors” at logistics giant XPO in Los Angeles and San Diego, and many more at smaller outfits.10Jonah Furman, “The week in US unions, January 15-22, 2022,” Who Gets the Bird, January 24, 2022. Union victories and a tight labor market in 2022 should encourage workers to join unions even given the risks that are involved.

That capital will not always fold easily in the face of strikes, however, is clear from how some strikes have been dragged-out for a long time due to employer intransigence. These include Steelworkers at Special Metals in West Virginia, construction concrete mix workers in Seattle, Bakery workers at Rich Products in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and airline pilots at Alaska Airlines who have gone three years without a contract.11Jonah Furman, “This week in US unions, January 29-Feruary 5, 2022,” Who Getsthe Bird?, Fruary 8, 2022. On the other hand, some of those bargaining this year have a track record of victories such as CWA members at AT&T, Hospital and education workers just about everywhere, and the nation’s 4,000 Teamster carhaulers who move cars from factory to dealer.

The carhaulers are a particularly important group because their national contract will be negotiated by the new leadership of the Teamsters representing a coalition of local leaders who broke with Hoffa over the last several years and the rank and file organization Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU). The last time the Teamsters negotiated with the carhaul firms TDU led the rejection of union-recommended offers twice, winning significant gains. Carhaulers also voted overwhelmingly for the Zuckerman United Teamster slate in 2016.12Teamsters for a Democratic Union, “Carhaulers Say No To Concessions & Hoffa,” Teamster Voice, December 8, 2016, https://www.tdu.org/carhaulers_say_no_to_concessions_hoffa; Teamsters for a Democratic Union, “Carhaul Teamsters Show How to Win: A Guide for Freight, UPS, and UPS-Freight Teamsters,” Teamster Voice, March 30, 2017, https://www.tdu.org/carhaul_teamsters_show_how_to_win_a_guide_for_freight_ups_and_ups_freight_teamsters This year will certainly see another clash between these companies and an unusually well-organized rank and file. A less well-known development in 2022 is the bargaining by 13 unions representing 115,000 railroad workers at the nation’s seven major freight carriers. The unions have declared an impasse which means bargaining goes to mediation and failing that the possibility of “self-help,” meaning a strike. Under the Railway Labor Act, however, strikes can be halted by the National Mediation Board (NMB). The current NMB now has a Biden-appointed Democratic majority, which means a possible test for the Biden administration’s real attitude toward labor action. Inside the various rail unions, the cross-craft rank and file organization Railroad Workers United is pushing for a strike.13Joe DeManuelle-Hall, “Rail Unions Are Bargaining Over a Good Job Made Miserable,” Labor Notes, February 2, 2022, https://labornotes.org/2022/02/rail-negotiations-are-about-good-job-made-miserable; Railroad Workers United (RWU), The Highball Vo. 15, No. 1, Winter 2022, 5-6.

This year’s bargaining round is, therefore, a contradictory setting in which capital wants to hold on to its outsized gains as supply problems threaten them and workers are developing both greater self-assurance and a hunger for a better life coming out of the depths of the pandemic. Given the start of militancy apparent in 2021, this year is certain to see some major conflicts not only between workers and bosses, but between the ranks and those leaders who hesitate to further this most basic struggle. The questions for socialists as for all workers is how many and how hard fought will these contract fights be and to what degree will these conflicts between capital and labor help to transform a labor movement still in retreat. Economic context and opportunity by themselves are not necessarily destiny.

In this context, those union leaders accustomed to a lifetime of negotiating retreat and concessions to capital or at best marginal gains in what became the routine practice of collective bargaining in the neoliberal era are by themselves unlikely to make up for what had been lost or given-away. To be sure there are exceptions to this grim reality. Nevertheless, encased in bureaucratic structures, business union ideology, and political dependence on business-funded Democratic politicians, this habit of accommodation by all too many top union leaders was bound to conflict with a new sense of value and spirit of resistance evident in a growing proportion of union ranks. This was apparent in 2021 as a number of major contract offers proposed by union leaders were voted down, sometimes more than once. So, the first big if in 2022 is whether the majority of today’s union leaders can be pushed into or pushed aside to allow for the kind of fights needed to undo the legacy of retreat many of them presided over or inherited.

For socialists who belong to the unions affected by bargaining this year, the task is to help organize rank and file actions both in confrontation with the employers through mass action and, where necessary, internal opposition to union leaders unwilling to take on the fight or who actually stand in the way.

This conjuncture points toward an almost certain increase in rank-and-file-initiated action both in terms of pressure to strike in the face of employer resistance and the rejection of inadequate offers from the employers. Contract rejections, once common in the 1970s but rare since, are one of the most basic forms of self-organized rank and file resistance in the context of conventional collective bargaining. As one of the oldest and most effective rank and file organizations, the Teamsters for a Democratic Union has demonstrated for years in contract fights in freight trucking, carhaul, UPS, and many smaller jurisdictions, contested collective bargaining situations can be laboratories for union reform and democracy. It is here that the most basic implementation of the rank and file strategy for socialist union engagement can be tested in practice in the coming months. It is only a starting point in the fight for the transformation of today’s unions or the creation of new ones into sites of workers democracy and power, but no less important for that. As Mike Parker and Martha Gruelle wrote in Democracy Is Power, still the most comprehensive guide to union democracy, “Union power requires democracy.”14Mike Parker and Martha Gruelle, Democracy Is Power: Rebuilding Unions from the Bottom Up, Detroit: A Labor Notes Book, 1999, 1.

The other actor in this drama, of course, is the Biden administration. Biden gave us a preview of his attitude toward labor militancy when he intervened on the side of Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot in the fight against and lockout of the Chicago Teachers Union for its actions in defense of teacher and student safety. The Biden administration is in crisis and paralysis facing opposition to Biden’s legislative agenda from the right of his own party. This, however, may not stop him from attempting to convince those labor leaders who see their fate bound up with the Democratic Party to moderate their demands and settlements and avoid economically disruptive strikes. It is rumored that Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh is already talking to the new leaders of the Teamsters whose carhaul contract expires in May. The likelihood of intervention is particularly strong if Biden and other Democratic leaders see strikes as hurting their already slim chances of holding on to their congressional majority in the 2022 midterm elections. In all likelihood, such interventions will be presented as even-handed, simply directed at achieving a reasonable and peacefully arrived at agreement. This is, of course, nonsense given the real balance of power and the issues at stake in bargaining. This is the second big if in this unfolding conjuncture.

Socialists and the actually existing class struggle

For most socialists organized working class power and self-activity are basics in the long term fight for socialism. Class struggle beginning even in its most rudimentary form lays the basis not only for immediate gains but for the increased power, organization, and consciousness needed to make socialism a possibility. The bargaining round of 2022 offers the potential to take some steps toward these necessary conditions for bigger fights to come. This involves more than statements of support or simply visiting picket lines whether by individuals, DSA branches, or elected officials claiming the title of socialist. The role of those who have expanded the ranks of socialists in the US to tens of thousands in the last few years is, thus, the third big if in the class confrontations of 2022.

It is estimated that DSA has about 10 or 11,000 union members. For socialists who belong to the unions affected by bargaining this year, the task is to help organize rank and file actions both in confrontation with the employers through mass action and, where necessary, internal opposition to union leaders unwilling to take on the fight or who actually stand in the way. Socialists should be encouraging on-going rank and file organization and caucuses in order to increase union democracy, leadership accountability, and deeper changes in the union culture. This is not a simple a case of militancy, but of a political understanding of unions as more than bureaucratic agents in today’s highly limited and legally curtailed system of collective bargaining. Recent victories in the Teamsters that brought about rank and file participation in bargaining and simple majorities to reject a contract are examples of small changes. Although the United Auto Workers (UAW) do not face contract expirations in its major jurisdictions this year, the reform movement United All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) has won the direct vote on top leaders and will face a difficult fight against that union’s entrenched Administration Caucus this year and beyond. The socialist vision of workers’ democracy should inform our actions in the unions during and after this year’s contract fights. In other words, for those who are union members, this is a chance to further the implementation of the much discussed and as yet too little practiced rank and file strategy.

The pressures not to expose and oppose the Democrats’ intervention on the side of capital will be enormous in the face of the midterm elections. Nevertheless, socialists need to publicly oppose such intervention as the political strike-breaking it is.

For those not in unions facing contract expirations there will be opportunities to organize mass support actions in cooperation with striking workers. One of the problems often faced by strikers is isolation from other unions and social movements. Socialists who are active in these movements can play a role in mobilizing support for striking workers from them. The idea of “swarming” the employers with mass support proposed last year by Rand Wilson and Peter Olney is one possibility.15Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, “Swarming Solidarity: How Contract Negotiations in 2021 Could Be Flashpoints in the U.S. class Struggle,” Labor Notes, January 14, 2021, https://www.labornotes.org/2021/01/swarming-solidarity-how-contract-negotiations-2021-could-be-flashpoints-us-class-struggle. Organizing other forms of public exposure, direct pressure on employers, and disruptive civil disobedience are other possibilities. This could be particularly important where the courts limit picketing by union members. A September 2021 Gallup poll points to the highest level of public support for unions since 1965 at 68 percent.16Megan Brenan, “Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point since 1965,” Gallup, September 2, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/354455/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx?version=print. To make a difference, this opinion needs to be mobilized.

There is a tendency among some socialists to see union-based struggles as merely “economic” or simply “unrest,” while electoral action rates as fully “political.” In some versions the very concept of “class formation” is linked only to electoral action and organization, labor “unrest” being something separate and inadequate to that process.17See, for example, Eric Blanc, “The Birth of the Labour Party Has Many Lessons for Socialists Today,” Jacobin, February 15, 2021, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/02/labour-party-uk-lessons-socialists ; and my reply Kim Moody, “Cutting history to fit a model,” Tempest, September 24, 2021, https://tempestmag.org/2021/09/cutting-history-to-fit-a-model. Aside even form the obvious interaction of the two in the development of consciousness and organization, such a separation of economic and political is untenable in modern class society where the state is deeply involved in labor-capital relations and conflict at every level. The institutional set-up of “industrial relations” in the US is a highly restrictive web of laws, courts rulings, state agencies, and political actors that makes even the most rudimentary labor-management conflicts political in any meaningful sense of that word. The class struggle under these legal and political restraints on labor, along with most employers’ accumulated wealth, render even the current more favorable terrain highly unequal. With the Biden administration likely to intervene in bargaining either openly or behind the scenes, with the pretence of an “even handed” mediator, the “political” nature of contemporary class conflict will be even more apparent.

It will be the job of socialists to expose and oppose government attempts to discourage, limit, or prevent strikes or other actions by labor. The pressures not to expose and oppose the Democrats’ intervention on the side of capital will be enormous in the face of the midterm elections. Nevertheless, socialists need to publicly oppose such intervention as the political strike-breaking it is. This will be a test for those socialists elected to office as Democrats who should be held accountable to openly expose and oppose any intervention by the Biden administration. The usual symbolic visits to picket lines or statements of sympathy are not enough. There must be a willingness to publicly expose a Biden administration intervention as political strike breaking. In turn, those who saw these elections as the real “political” thing, have an obligation to hold those they helped elect to the basic socialist standard of class solidarity—as in “which side are you on?”

DSA’s thousands of activists along with others on the left in the social movements have a major role to play in this year’s class struggles and the numbers to make a difference in an effort that can, for once, unite much of the left. In a way, this is the first chance for this sort of intervention on a scale that can matter in a very long time and a potentially formative experience for a new generation of activists. It would be a political tragedy to miss this opportunity.