The Mothers of May, inspired by the Argentinian women from the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, is a movement comprised and built by mothers, family members, friends, and advocates that fight against state violence, mass incarceration, and black genocide in Brazil. The movement was created after the May Crimes of 2006, explained by Dina Alves as one of the most emblematic cases of impunity in the post-military dictatorship period. It is estimated that between May 12 and 21, up to 500 people were murdered by São Paulo police forces – which exceeds the number of people killed by the state during the Brazilian military dictatorship over its 21 years of existence. The claims for justice and truth continue as the mothers, 16 years later, engage in the collective struggle toward answers for their missing and dead children.

In the third installment of the series, which appeared in Portuguese here, the anthropologist, Black feminist, and Brazilian lawyer Dina Alves presents the main demands of the movement. She reflects on its unique analysis of the Brazilian state and shows how its continuing struggle for justice, reparations, and collective memory reveals the core content of Brazilian democracy: as a democracy of genocide built on the myth of racial democracy.

The series’ first installment, “Building Grassroots Politics in Militia Territories in Brazil,” can be found here. The second, “Looting, Dispossessing, Incarcerating,” is available here.

–Margarida Nogueira

Translated by Margarida Nogueira

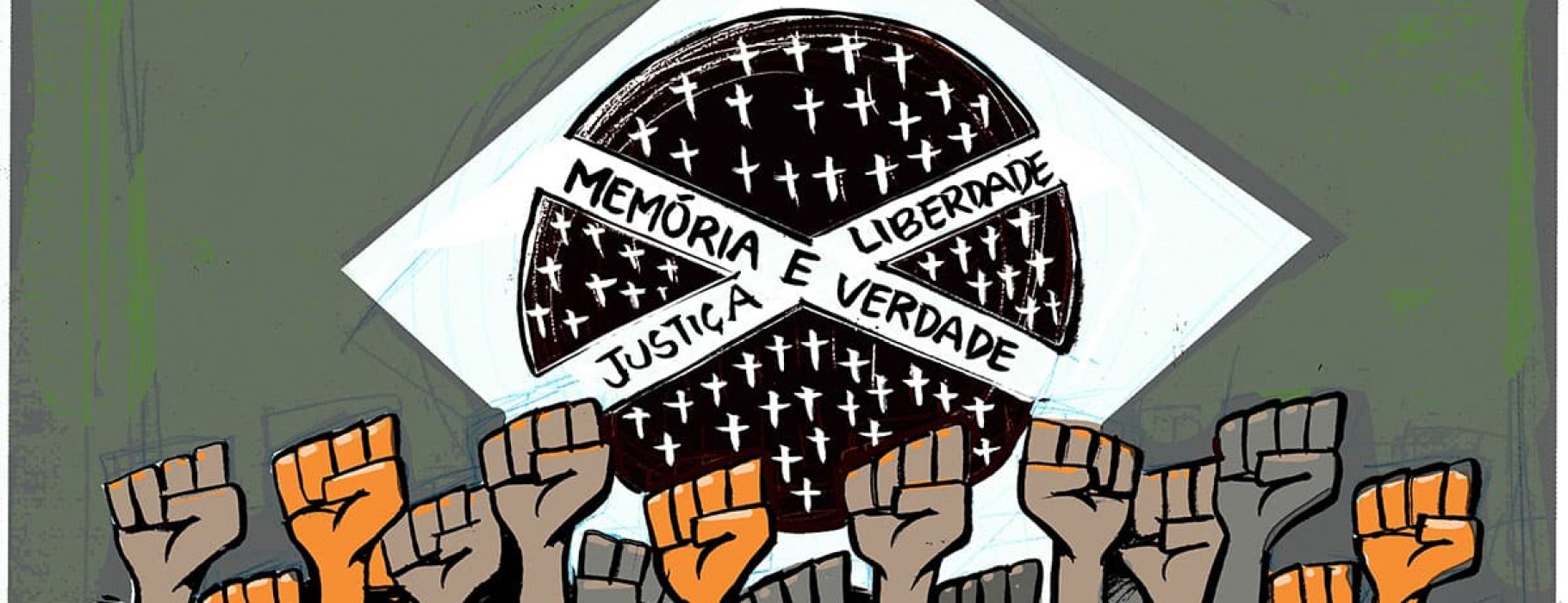

The demand for memory, justice, and truth is the agenda of the Independent Movement Mothers of May [Mães de Maio]. This agenda reveals the urgency of a solid and genuinely human democracy at a civilizational level in Brazil – a democracy in which not only the victims of state terrorism, but all of society is called upon to think about how the state manages its racial necropolitics. That is, this is an analysis of how the state elaborates its deliberate choices (or not) about who should live or die in society. In other words, the Mothers of May platform helps us locate structural racism in the constellation of institutional policies, beliefs, discourses, and knowledge in the unequal distribution – intentional or otherwise – of death and punishment in contemporary Brazil.

These constitute historical questions without any pretension of hasty answers here. In these lines, I want, on the one hand, and as a Black woman from the favela, to feel authorized to put forward some hypotheses about this subject. On the other hand, not being a biological mother, I ask permission from the Mothers of May, with whom I have had the opportunity of walking along over these past fifteen years of struggle, and offer some clues about the ways in which structural-institutional racism, intrinsic to the project of the nation-state, presents itself in the administration of justice and organizes its genocidal enterprise.

The May Crimes [Crimes de Maio]1The May Crimes of 2006, in the city of São Paulo, represent one of the most emblematic cases of impunity in the post-military dictatorship period. Between May 12th and 21st of 2006, more than 500 people were executed in the state of São Paulo and, officially, at least 124 (one hundred and twenty-four) demonstrably innocent people were killed by police forces. In that same year, the criminal organization First Command of the Capital organized simultaneous rebellions in prisons throughout the state of São Paulo. Outside the prisons, the criminal organization carried out a series of attacks, setting buses on fire, attacking public building and, specially, attacking the police, including police cars, police stations, and battalions. In response to the attacks, the entire São Paulo police force was put on standby, and soldiers’ vacations and leaves of absence were revoked. According to the most recent research coordinated by the Movement Mothers of May and by the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) the police officially killed at least 124 civilians, under the false narrative of “resistance followed by death.” are considered the biggest massacre in recent memory in contemporary Brazil – certainly since the fall of the dictatorship in the 1980s. They are, therefore, termed “democratic genocide” by the Movement. Since 2006, these women have left the favelas and communities, the houses where they worked, and have taken over the streets and the world. They politicized Black motherhood, surpassed borders, and, much to the dismay of the white elite, internationalized the fight. They have created an uneasiness across Brazil by denouncing anti-Black genocide in a society founded on the myth of racial democracy.

An understanding of their experiences requires us to critically examine myths about “justice” and “truth” produced by institutional discourses. Their trajectories are central to understanding the “invisibility” of Black women in the access to constitutional rights, among them the (non-)access to justice, as a fundamental right in a democratic society, and to understand the hypervisibility in the criminalization of their bodies, marked by the stigmas of “mothers of drug dealers” or “mothers of criminals.” The control over the representation of these women is highlighted in a statement made by the São Paulo prosecutor Ana Maria Frigério Molinari during a hearing in which she claimed that the women who are part of the human rights movement of people murdered in 2006 were “mothers of drug dealers.” According to the representative of the prosecutor, “After the death of their sons, in May of 2006, they started to manage the drug sales points, with the help of the criminal organization First Command of the Capital. Some of these people died in the May crimes and the rights [to manage the sales points] are passed on to family members that, sometimes, manage or even lease the drug trafficking spots.”

This criminalization of Black motherhood – often their parental rights are suspended because they are treated by the courts as promiscuous, pariahs, morally corrupt, and dangerous drug dealers – is part of what Patricia Hill Collins has aptly called the strategy of image control of Black women.

These stereotypes reveal the multiple oppressions that cross the experiences of women for being Black, poor, lesbian, trans, mothers, grandmothers, indigenous, migrant, Palestinian, Latinas, confined in prisons and jails, or joining the ranks of these spaces on the outside, “pulling jail together.” This criminalization of Black motherhood – often their parental rights are suspended because they are treated by the courts as promiscuous, pariahs, morally corrupt, and dangerous drug dealers – is part of what Patricia Hill Collins has aptly called the strategy of image control of Black women. These strategies of pathological representations are given a new lease on life when they are widely shared by public authorities. Other official statements give us the dimensions of the disastrous consequences that fall on them. Jair Bolsonaro, Hamilton Mourão, and Sérgio Cabral, respectively, justify their political projects by affirming that: “the children of social welfare programs beneficiaries have a slower intellectual development than the world average”; or “the home that only has a mother and grandmother is a factory of misfits for trafficking”; and also, “the fertility rates of mothers from the favelas are a factory of delinquent production.” These pathological scripts attributed to racialized mothers, such as “factory of delinquent production” and “mothers of drug dealers,” take up space and action in the social imaginary in general, and they are produced in the editorials of the hegemonic media and commonly justified in court sentences to motivate punishment. These are the distinct methods of criminalization that articulate and operate the militarized policies of public security.

This reveals the macabre side of the anti-Black genocide that acts not only in the extermination of children, but also in the mother’s illness and premature death. They struggle against the multiple manifestations of Black genocide. The prevalence of symptoms of sickness is an example of that: profound sadness, anxiety disorders, symptoms of depression, stress, and health problems in the organs related to maternity, such as uterine, breast, and ovarian cancer, are all prevalent among them and confine them to a vicious cycle. The deaths of their family members produce deleterious effects on their personalities. Rute Fiuza, representative of the Mothers of May in the northeast region and mother of Davi Fiuza, who disappeared under democracy, informs us of the destruction of maternal identity: “[T]oday I am no longer Rute Fiuza, I am Davi’s mother. This is how people call me. This is how society knows me.” Criminalization, racism, and punishment are part of the same processes of racial subordination.

Consequently, the struggle of the mothers is not limited to the penal aspect, or to the re-establishment and maintenance of social tranquility, or the facilitation of reconciliation processes to preserve the democratic rule of law. Barbarism cannot be humanized. No! The standpoint (lugar de fala) claimed by them is the standpoint of multiple voices, of the Black rebellion forged from the ground up, in the underground of their experiences of pain and grief. I want to point out that the “standpoint” that I talk about here is not associated with a version of the concept that is blatantly emptied of political meaning, which habitually hijacks other voices in the name of personal projects and in the limited anti-racist discussion, which ends simply by including discriminated people in the capitalist-punitive society. The arrogance in defining “being a Black woman” from a capitalist hegemonic view in no way challenges the neoliberal discourses. In fact, this trend presents itself as a prescription of predatory neoliberal policies that only replenish the needs of the consumer market and commodify the historical agendas of the truly radical Black feminist struggle committed to another form of sociability. Here it is essential to recall the words of Audre Lorde, according to whom “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

The numerous voices in the fight for justice, reparations, and memory refuse the racial production of official truth. They propose to dismantle the racist structures fortified by the myth of racial democracy. They invite different forces on the left to overcome their civil rights agendas and work toward the construction of another possible world, insofar as abolition is the claim for the life of the wretched of the earth. It is in this sense that the demands, built in these 15 years of struggle and hope, embody their historical experiences of resistance, worldviews, knowledge, pain, and subversion. If the elites manage the tools of the state and produce fables of justice and truth, it is this subversive, maddened, and brutalized corporal cartography that demystifies these conceptions and poses the challenge to give birth to another Brazil.