In the days since Trump’s ragtag army invaded the Capitol building on January 6, numerous politicians and media commentators have had their say, many of them pointing to the diverse forms of phantasmatic projection circulating among this scrambled “mob.” This is, we are told, a pretend legion consisting of QAnon saviours, Civil War reenactors, off-duty troops, miscellaneous trolls, Christian evangelicals, out-and-out fascists, anti-hipsters (similar beards, different tattoos), assorted Boomerwaffen, with the Commander in Chief, overweight and pulsing in radioactive orange, is cast as Captain America.

One is reminded of that famous passage from Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire: “Vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars.” This jumble may understate other kinds of social coherence involved in the contemporary right-wing crowd, and the character list is certainly different (though “discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds” rings true). But the only term to describe an insurrection that features a white supremacist shaman is “postmodern,” a situation where any image, or belief, can seemingly be combined with anything else.

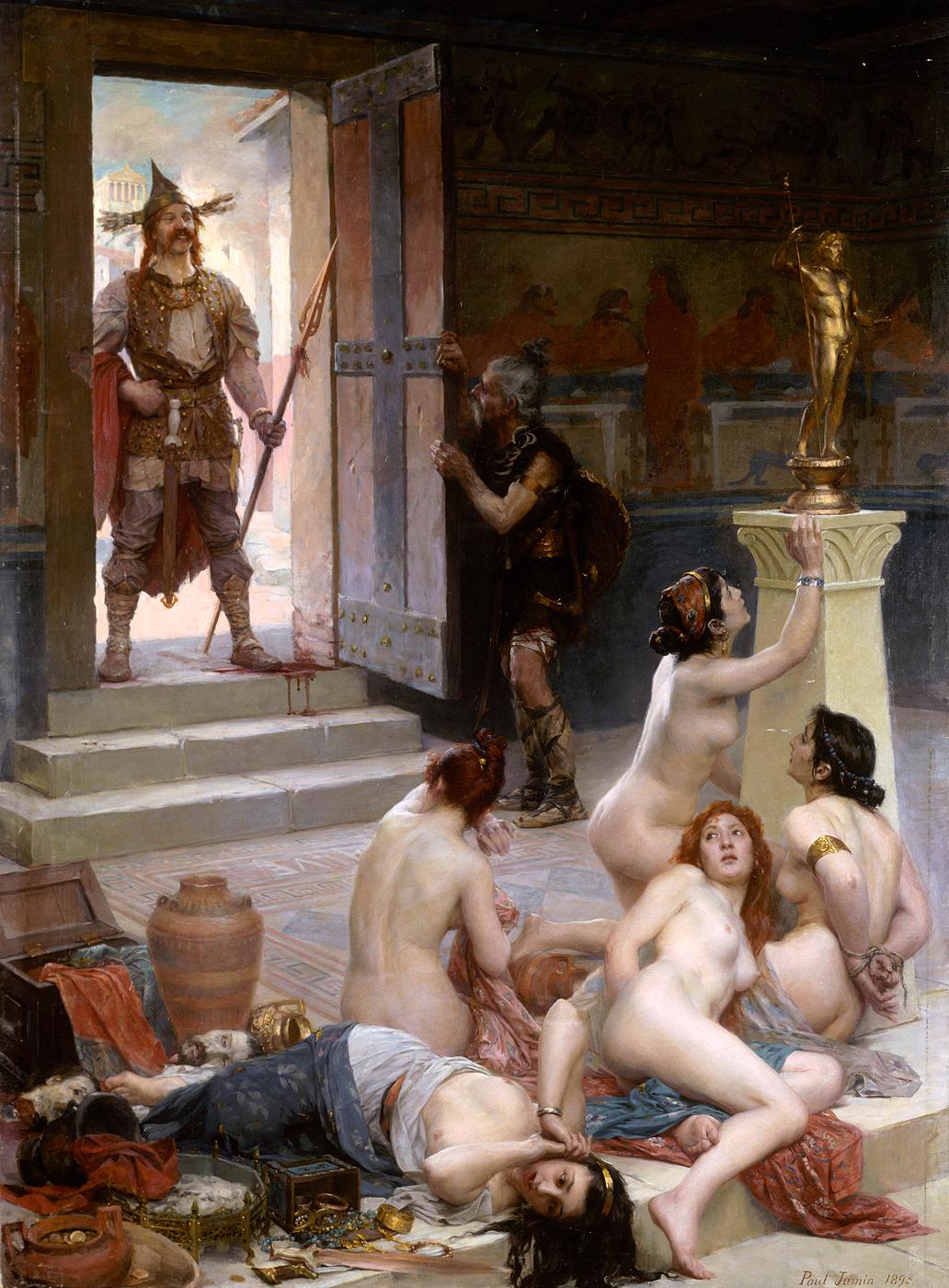

Mike Davis, in his contribution to Sidecar, plays this perception in comedic mode, deflating some of the aggrandizing rhetoric of the defenders of business as usual, return to civility or a new normal: “a big biker gang dressed as circus performers and war-surplus barbarians” is a wonderful and disturbing image. It is genuinely difficult to know whether the phobic delirium in evidence is best captured by The Eighteenth Brumaire or E.P. Thompson’s “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd,” where political confrontation is played as the push-and pull of theater.

As Adam Gopnik noted on B.B.C. Radio 4 last week, the antics of Trump’s contemporary Far Right are often played as comedy or carnival, until they are not. There are certainly echoes in the events on Capitol Hill of those British Republican conspirators, from Pentrich to Merthyr, who believed that a decisive action would spark the general rising. I’m tempted to think it is Thompson’s conception that helps best, unless as Richard Seymour noted (dread the thought), “First as farce, then as tragedy.”

What the commentariat hasn’t yet noticed is the way in which the stage iconography for this mini-drama – let’s hope it is a play in one act – infuses their own understanding of what took place, shaping the idea of invading barbarians. There is a photograph by Shawn Thew, made from inside the building, that focuses this point. Viewed through a dark aperture, the left-hand portion of the image, projecting diagonally into the space, is filled with a bronze neo-classical frieze. It is a fragment from Randolph Rodgers’s Columbus Doors of 1910. This portion of the picture is dominated by the panel known as the “Right Valve: Death of Columbus (1506).” Outside, beyond the door and bathed in a Claudian soft, bright light, are a cluster of Tuscan pillars, cropped four or five feet from the ground by the photographic frame. A broken column, which the cropping of the image suggests, was often used in funerary monuments. On the ground plane, amongst the discarded trash and glass shards, there lies a scarf or a pendant – red, white and blue – emblazoned with “TRUMP.” The photographer may have serendipitously come across this detail, or possibly he arranged it like this. It is what makes his carefully composed image.

Amidst the sound and fury of liberal indignation, insiders in business suits and outsiders wearing denim and camo struggle over the same set of signs.

Move from the Columbus doorway inside the neo-classical rotunda of the Capitol building, where riotous action also took place, and we see more of the same iconography portrayed on the bronze doors. High on the walls are four marble busts of the discoverers: Cabot, Columbus, Raleigh, and La Salle, all framed with laurels. The eight large paintings apparent in the news footage are four scenes depicting the War of Independence by John Turnbull, from 1817-1824 and a further four large paintings by different artists: The Landing of Columbus (John Vanderlyn); Discovery of the Mississippi (William Powell); Baptism of Pocahontas (John Chapman); and Embarkation of the Pilgrims (Robert Weir). There are also four relief panels portraying the Landing of the Pilgrims (Enrico Causici); The Conflict of Danial Boone and the Indians (Enrico Causici); Preservation of Captain Smith by Pocahontas (Antonio Capellano); and William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (Nicholas Gevelot). Statues in the space range from Washington to Reagan. In the Cupola itself, The Apotheosis of Washington by Constantino Brumidi presides over everything

Commentators seem to have rapidly forgotten the recent debate over racialized monuments. Set in neo-classical architecture, invoking the supposed long durée of that imaginary signifier “Western civilization,” viewers are presented with visions of heroic settler colonialism, the mythology of Christian conversion, airbrushed genocide, and Romanticized “savages.” There isn’t an African American to be seen – the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was added in 1986, and more recently Sojourner Truth and Rosa Parks, seeming attempts to compensate for the overwhelming emphasis on a heroic elite whiteness. This is the symbology of a Herrenvolk democracy. In the invasion of the citadel, one set of supremacist fantasies faced off against another imaginary order. Amidst the sound and fury of liberal indignation, insiders in business suits and outsiders wearing denim and camo struggle over the same set of signs.