Socialist Contagion in a Time of Pandemic

Spectre introduces itself at a moment of world-historical crisis.

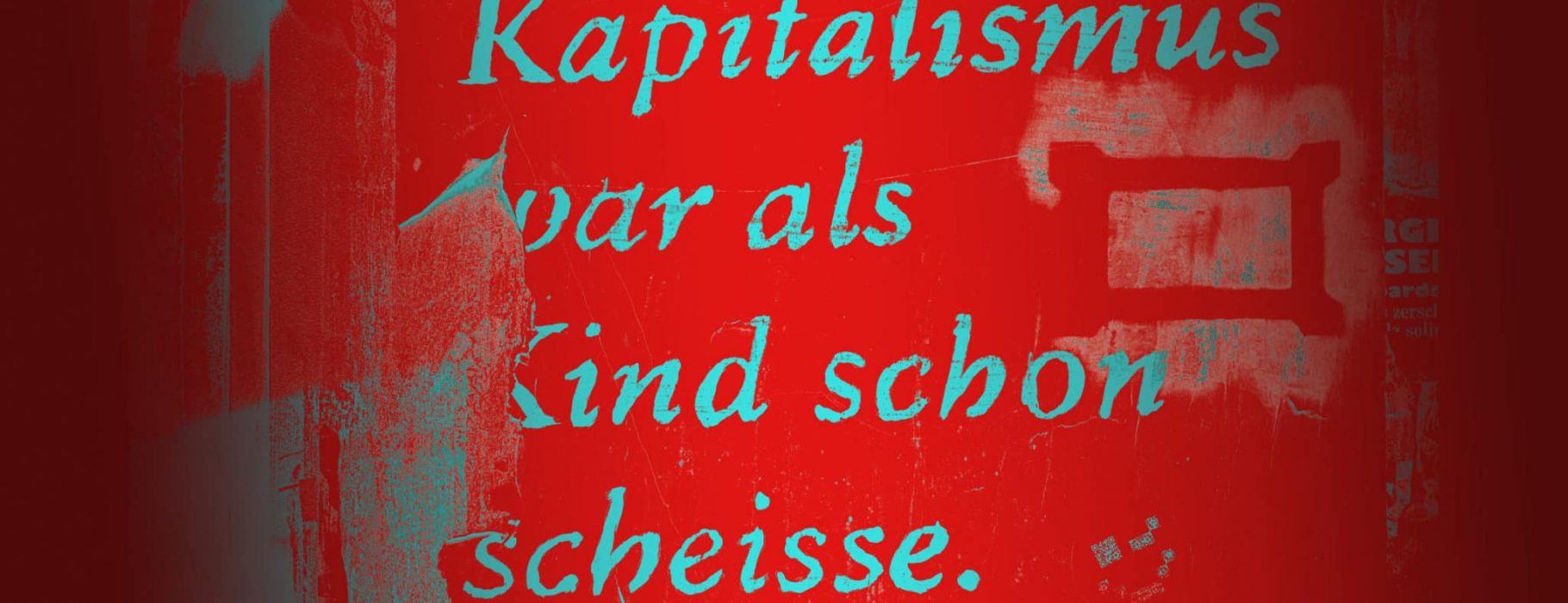

A global pandemic has catastrophically amplified the economic recession that began in the autumn of 2019. Millions of lives are imperiled as multiple contradictions of capitalism—ecological, economic, social-reproductive, and bio-medical in particular—explode simultaneously.

There is much we do not know about what our world will look like in six, twelve, or twenty-four months.

But this we do know. That global capitalism has demonstrably failed. That the only genuine alternative is a system of socialist democracy, planned economy, and world cooperation. That none of this can be achieved without years of mass struggle and socialist organizing internationally. And that the ruling class is frantically regrouping to survive this crisis and reimpose its domination—by ever more authoritarian means where it deems that necessary.

We can see ominous forebodings of this in the closing of borders to migrants and refugees, in the invocations of war-time powers, in the promotion of anti-Asian racism, in state decisions to save banks rather than the poor, the homeless, and the dispossessed.

This crisis exposes the capitalist imperative to accumulate monetary value at the expense of the conditions for the reproduction of life, both human and non-human. And once more, women are bearing the brunt of it—as nurses, caregivers to the elderly, and those who pick up the slack in the household.

Fortunately, the human lifeworld refuses to sit still. Mothers organized into Reclaiming Our Homes have seized vacant housing in Los Angeles, insisting that lives come before property rights. Wildcat strikes by Detroit bus drivers, Amazon warehouse workers in Italy, autoworkers in Canada, among many others, have won anti-virus protections at work. In Argentina, worker-controlled enterprises have elected to produce alcohol gel and masks for the healthcare system. In city after city, activists have forced a halt to evictions, urging that no one will be made homeless in the midst of pandemic. Private hospitals in Spain have been commandeered to treat people for free. And veterans of the struggle against the HIV-AIDS pandemic are instructing activists on how to organize in the face of Covid-19.

To be sure, these acts of resistance are just the beginning, none of them equal to the momentous tasks before us. For these we need nothing less than to break the domination of capital. Yet all of these acts carry germs of resistance and solidarity that might breed anti-bodies to capitalism. And that is where Spectre comes in. Our job is to deepen that socialist contagion. By providing a site for revolutionary theory, political analysis, and historical study, we seek to foster a new insurgency.

Of course, the work a radical journal does can never be sufficient. But it is necessary. Writing from a fascist prison cell in the 1930s Antonio Gramsci observed that, “the old is dying but the new cannot yet be born.” We inhabit a similar moment today. And we make one unflinching commitment to our readers: Spectre will mobilize its meager but precious resources to hasten the birth of the new. We will bend all our efforts to assisting the growth of socialist movements dedicated to attacking the virus that is capitalism.

Once again, a spectre haunts our world: the spectre of communism. By “communism” we do not refer to the bureaucratic, nationalized economies that until recently masqueraded as socialism. Instead, following Marx, communism is “the real movement which abolishes the present state of things”1—the movements of working class and oppressed peoples against capital. As right-wing regimes encircle the globe, spreading from DC to Delhi and from Britain to Brasília, they everywhere encounter opposition.

The real movement against the existing state of things is found beyond the electoral arena: in particular, in the return of the mass strike. In France, an investment banker-in-chief’s crack at weakening pensions transformed tens of thousands of “Yellow Vests” into hundreds of thousands on the picket lines. One out of every eighteen Chileans mobilized against austerity, with workers across many sectors striking in solidarity. In Brazil, Bolsonaro was met with a general strike of 45 million, while four times that number struck against austerity and Hindu nationalist violence in India. Those who thought they would rule peacefully over the corpse of the Arab Spring are facing new movements in Beirut, Baghdad, and beyond.

Climate change begins its disaster phase, and “climate refugee” enters our vocabulary for the first time. In the face of denialists and do-nothing incrementalists, transnational movements demanding immediate solutions grow daily. Wars both formal, as in Syria and Iraq, and informal, as in Central Africa and Central America, send waves of refugees toward Europe and America, only to be met with official disdain and brutal repression by states and proto-fascist vigilantes. Meanwhile, a global pandemic is met with efforts to close borders rather than socialize healthcare and enhance workers’ rights to sick leave and safe work. Against this exclusionary conception of the world, another politics beckons: crowds occupy airports and storm borders, transforming “no one is illegal” from a phrase into a reality.

The era of “there is no alternative” to capital’s rule is behind us, but what lies ahead? This latest resurgence of socialism again poses questions that the left has debated for well over a century: Is it possible to reform and regulate capitalism? Can the working class make use of the existing state to transform society? Do working people still possess the social power to transform the world through their struggles? How do we help the working class forge itself into a universal, collective force while attending to the real divisions within the working class along lines of race, nationality, citizenship, gender, and sexuality? How do we build a socialism that is antiracist, feminist, pro-queer, and ecological?

Enter Spectre. While we are a US-based journal, we are resolutely internationalist in our outlook. This means that we draw extensively from the experiences of both historical and contemporary struggles across the globe. We have no illusions that our politics of socialism from below is the “common sense” of this new generation of resurgent socialists. As we see it, our task is to make the case for radical politics in the new socialist movement by advancing clear and concrete analyses of the current realities, while constructively engaging in strategic debates running through our movement.

Spectre seeks a politics rooted in the real self-organization and self-activity of the working class. As this latest wave of working class activity reaches our shores, many look to forces from above to organize and direct any emergent movement. But as New Deal parallels abound, we mustn’t forget that FDR—an establishment figure who was only driven to reform, rather than to transform—rode an upsurge of mass struggles to power in the 1930s. Today, however, the argument is generally reversed, namely, that social democrats in office will facilitate working class militancy. The hope, in other words, is that a new movement will produce its own enabling conditions primarily through electoral victories.

But will it? The groundswell of resistance wasn’t immaculately conceived by an electoral campaign. Rather, it was born in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, growing in spurts, stalling then starting: from campus occupations to the Wisconsin Uprising, from Occupy to Black Lives Matter, from the Dakota Access Pipeline blockades to airport shutdowns, from the International Women’s Strike to the strike waves of teachers and health care, hotel, and auto workers.

It is only in the context of these real social struggles that we can make sense of the new salience of the communist idea. While the ascendance of social democratic electoral movements is welcome, once in office such regimes generally fail to fulfill even the most minimal hopes of radicals and socialists. For all the excitement generated by a Bernie Sanders or a Jeremy Corbyn, we need to understand the roots of the failure of Syriza in Greece—not to mention prior experiments in parliamentary social reform from Chile to Sweden to Tanzania. We need similarly to understand, especially in the US, the inherent limits of parties of the capitalist class for the advance of the socialist project.

A Labour victory in Britain or the election of Sanders in the US could certainly inspire new working class currents and amplify the power of their demands. But elections alone cannot take us beyond capitalism, or even win and secure new gains for our side in the class war. Without prior and ongoing working class mobilization in the workplace, the communities, and the streets, electoral victories have not prevented new rounds of austerity, continued decimation of unions, increased police targeting of youth of color, ramped up repression at the borders, and the like.

Anti-oppression struggles are not alternatives or even supplements to class struggle but constitute key elements of the class struggle in the present era.

A second major problem with any socialism-from-above approach is that it usually relies on an abstract vision of working class unity constructed from on high, while ignoring how in their everyday lives workers are pushed together and pulled apart by capitalism. Any alternative politics must proceed from people’s lived conditions of existence—from the actually existing working class in all its differences and diversity. Socialists should not be in the business of persuading Black workers facing racist police violence that they need to focus on “unifying” demands, as if the demand to be free of capricious state violence is somehow not already universal and working class in character. Nor should we be lecturing queer workers or undocumented immigrants that their concerns are “narrow” or merely “identity-based.” Such an approach is a socialist variant of trickle-down economics: it assumes that unity proclaimed at the top finds its reflection below. Any Marxist politics that does not begin from the real differences among working people will never be able to develop into a truly universal politics.

We reject the politics of prioritizing so-called “universalist” campaigns over struggles against racial domination, patriarchal subjugation, cis-heterosexist erasure, Islamophobia and antiSemitism, xenophobia, and imperialism and nationalism in all their beastly guises. Insofar as there is a unified position at Spectre it is this: these anti-oppression struggles are not alternatives or even supplements to class struggle but constitute key elements of the class struggle in the present era.

If the emergent socialist left is serious about helping to reconstitute working class unity, we cannot remain willfully indifferent to the actually existing fragmentation of workers or to the demands for solidarity that arise from their struggles. Feminist calls for reproductive autonomy, campaigns against racist police terror, movements for the abolition of all border patrols or for free gender affirmation on demand: these aren’t simply limited skirmishes. Insofar as each of these struggles serves to integrate sections of the proletariat, moving to unify them in fits and starts, these “particular” struggles are integral elements of the universal struggles we seek to build.

This is where Spectre comes in. Rather than building an echo chamber or advancing a single political or organizational line, we seek to create a venue for discussion and debate on the revived left—a left we see as emerging from 2008 rather than 2016. To this end, we seek to elaborate a comradely range of revolutionary socialisms and to invite debate, disagreement, investigation, rethinking, research, and polemic.

To be clear, we remain wary of putting our eggs in the social democratic basket. But we are equally suspicious of critics who take pleasure in denouncing the reformist turn from a place of insular detachment. Marxism is engaged, or else it fails on its own terms; it is a practice rather than a gesture.

And while rejecting one-size-fits-all universalism, we also question any individualized brand of point-scoring framed as identity politics. We see these as two sides of the same undialectical coin, two routes to a dead end.

Here at Spectre we are especially keen to publish articles on questions related to working class feminism, racialization under capitalism, migration and borders, anti-imperialisms, anticapitalist queer and trans* critiques, ecosocialisms, indigeneity and land reform, the state and Marxist strategy, union and shop floor radicalism, and all other modes of anticapitalist and pro-working class analysis. It goes without saying that we are resolutely internationalist in our outlook, and we especially welcome engagement with contexts beyond the US and Europe. We will try to prioritize global and transnational work, as well as writing that seeks to build solidarity across borders and all other existing divisions within the global working class.

We are equally resolute in our opposition to imperialism. While the period of formal colonial rule may be over, the impact of imperial domination remains ever present in much of Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Latin America, not to mention in postcolonial diasporas across Europe and the Americas. Across the globe, new working class movements, strikes, and mass struggles are arising. Our solidarity is with workers in motion against imperialism in any form and against the ruling class of every country.

We remain wary of putting our eggs in the social democratic basket. But we are equally suspicious of critics who take pleasure in denouncing the reformist turn from a place of insular detachment. Marxism is engaged, or else it fails on its own terms; it is a practice rather than a gesture.

We refuse to align ourselves with autocrats like Putin in Russia, Xi in China, and Assad in Syria, who remain enemies of their own respective working classes. When these rulers crush uprisings and strikes, they set back struggles against imperialism and capitalism many years. Our internationalism is not based on siding with one capitalist state over another but with unwavering solidarity with the struggles of the only collective agent of any progressive importance: the global working class.

This inaugural issue of Spectre opens with David McNally’s “Return of the Mass Strike.” In a sweeping panorama he analyzes the past two years of mass struggles from a global perspective. While McNally is hardly the first to analyze these revolts, his insistence that the return of the strike underlies this resurgence is unique. He argues that the self-activity and self-organization of a remarkably heterogeneous working class is central to any understanding of the current geography of resistance. A second installment will revisit his argument in relation to the classic mass strike debate prior to World War I, insisting upon its relevance for today.

McNally’s piece is followed by a provocation from philosopher Vanessa Wills. Entering into the fraught debate over “white privilege,” she argues that there are in fact two contending theories passing under that name. One is a liberal version that conceptualizes privilege as a personal asset, as individualized and asocial. The other, Wills argues, can be derived from the work of W. E. B. Du Bois. It was Du Bois who described a set of relative advantages grounded in the racial and class relations of capitalism, and Wills extends this approach into a broader materialist analysis of white privilege today—one she explicitly poses as an alternative to the liberal version.

Also entering into the debate over racism under capitalism is historian Edna Bonhomme, with her powerful case for reparations today. After explaining the difference between liberal and Marxist demands, she provides a globally situated analysis of Haiti’s experience with slavery, colonialism, and imperialism in order to emphasize the need to internationalize the debate over reparations. Bonhomme concludes by showing how internationalism underwrote the success of the Haitian Revolution, drawing lessons for the necessity to look beyond the US by reframing reparations struggles today in global terms.

Turning to questions of migration in the current conjuncture, philosopher Ashley Bohrer asks us to consider immigration as a process of socially reproductive labor. She argues that this may be a site and source of labor by migrants, available both to employers as a source of surplus value and, potentially, to the working class as a force for transformation. Her analysis explores the value of free movement for working class people against the backdrop of state violence, barricaded borders, and the rapaciousness of capital.

In a considered engagement with Sophie Lewis’s recent book Full Surrogacy Now, Sue Ferguson takes up the notorious rallying cry of the Communist Manifesto that Lewis has helped revive: Abolish the family! Moving beyond the reactive responses to the book that have appeared in both mainstream and left-wing venues, she delves into the implications of some of Lewis’s central assertions. These include fundamental debates over species-being, work, labor, gender, and reproduction, raising the question, what parts of our bodies “work”? If you have been following this debate across the London Review of Books, Catalyst, The Tucker Carlson Show, New Politics and Twitter, Ferguson’s review is definitive and not to be missed.

Finally, the issue concludes with two book reviews. Cinzia Arruzza critically engages Sue Ferguson’s recently released book, Women and Work: Feminism, Labour, and Social Reproduction, thinking about it in relation to social reproduction theory and autonomism. And Jeff Webber reviews Marian Schlotterbeck’s Beyond the Vanguard: Everyday Revolutionaries in Allende’s Chile, a careful study of on-the-ground militancy in the run-up to the election of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government in Chile in 1970. More than simply a book review, Webber maps out the Chilean political terrain in this period, drawing lessons for today.

In future issues, you should expect much more of this kind of developed engagement, further debate, and deepening of Marxist analysis. This year we will publish a second issue, in hopes that we might soon expand our publication schedule. We are living through the greatest opening for “a real movement that abolishes the present state of things” in many of our lifetimes, yet simultaneously the most extreme peril humanity has ever faced: seemingly unceasing economic crisis, rapid climate change, the spread of a global pandemic, and the uprooting of huge sections of humanity without any obvious place to go, to name but a few. We don’t want to come off as Pollyannaish. We face incredible hurdles, both from a renascent right and the doom merchants of capital, and surmounting these barriers is going to require quite a bit of strategizing. A journal is, of course, not a revolution or even a party. But it may play some modest role in contributing to what comes next. Without theory, there’s no adequate practice, and thus we bring you Spectre.

1 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The German Ideology (New York: Prometheus, 1998), 57.