The Politics of Colonial Comparison

Interview With Sam Klug

June 10, 2025

How did the global struggle for decolonization impact Black political thought in the United States? And more specifically, how did US understandings of decolonization (and therefore of colonialism) shape domestic debates over race and class in that country? Sam Klug’s new book, The Internal Colony: Race and the American Politics of Global Decolonization, takes up these questions directly by tracing the “politics of colonial comparison” over the three decades between World War II and the waning of the Black Power era.1Sam Klug, The Internal Colony: Race and the American Politics of Global Decolonization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2025). Spectre’s Zachary Levenson interviews Klug about his timely intellectual history, which forces us to rethink some of the dominant narratives of US Black radicalism in this period and advocates a properly internationalist frame.

Sam Klug is an Assistant Teaching Professor in US History at Loyola University Maryland. The Internal Colony: Race and the American Politics of Global Decolonization is his first book. His writing has appeared in Politico Magazine, Boston Review, Dissent, and other venues.

The book does present a genealogy of the concept of the internal colony, but it does so in service of answering a broader question: how did Americans understand the implications of global decolonization for supposedly “domestic” problems of racial and class inequality? Tracing the history in Black political thought of conceptions of African Americans as an “internal colony” or a “domestic colony” between the 1930s and the 1970s demonstrates the centrality of the unfolding process of global decolonization to African American thinkers and activists—as reference point, as inspiration, and as site of conceptual innovation.

Exploring the history of the internal colony concept also opens a window onto a broader field of comparative thinking. From the 1940s through the 1970s, the question of how to define colonialism, and how to think about its relationship to forms of racial and economic inequality within the United States, mattered a great deal to US elites as well as to Black activists. Foreign and domestic policymakers, as well as their allies in nonprofit foundations and the academy, insistently drew lines of comparison between the decolonizing world and various aspects of US society, particularly in relation to debates about international development policy and domestic social policy. These figures formed a set of counterconcepts to that of the internal colony taking hold among Black thinkers and activists in the same period. And, I argue, these competing interpretations of the meaning of colonialism, the political economy of the decolonizing world, and the relation between colonial rule and the political order of the United States contributed to the growing rift between postwar liberalism and the Black freedom movement.

The idea of “the politics of colonial comparison,” which I use throughout the book, draws on the work of a number of theorists and historians, from Manu Goswami and Brent Hayes Edwards to Ann Laura Stoler, whose work on “the politics of comparison in post-colonial studies” has had a major influence on me. The aim of the phrase is to indicate that making comparisons is an act that carries with it implicit or explicit political content. Therefore, I treat the comparisons made by historical actors as objects of study, rather than engaging in a comparative history that employs comparison as a method.

In part, I came to the project out of a frustration with the way that many American historians (and perhaps especially intellectual historians) have taken the Cold War as the only international dynamic that matters to the political vocabulary of postwar US life. Reading widely in Black political thought, anticolonial political thought, the history of decolonization, and work in US history, gave me the sense that there was another story to tell about how interpretations of colonialism and its end had provided important keywords to struggles over US racial and class inequality in the twentieth century.

I started working on this project in 2015, and the early phase of the Black Lives Matter movement during and after the Ferguson uprising had a profound influence on the questions I was asking in my research. So, too, did conversations about the relatively low priority placed on internationalism and anti-imperialism in the early post-Occupy renaissance of the US left—something that has dramatically changed, for the better I think, in the intervening decade.

The vision of colonialism as a system of racialized economic exploitation encompassed a range of social processes. This should not be surprising, as the history of radical analyses of imperialism and colonialism has always been attuned to the malleability of colonial exploitation. We can see this in the 1910s, when Hobson, Luxemburg, Lenin, and Du Bois all argued in different ways that colonies were becoming less economically important to their empires as sources of raw materials—either as inputs in production or as export commodities—and more important as outlets for surplus investment capital and markets for overproduced goods.

Similarly, for the Black intellectuals and activists at the center of my narrative, the modes of racialized economic exploitation that were analyzed using concepts of colonialism and internal colonialism shifted alongside changes in the organization of capitalism, and, of course, varied depending on a particular thinker’s point of view. The superexploitation of Black labor was a common thread for many of the figures I analyze. For Du Bois in the 1940s, especially in his 1945 book Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace, colonial racism served as a means to ensure that colonial powers could “secure labor at the lowest wage” in Africa. In the 1960s, for the SCLC activist Jack O’Dell, internal colonialism was a helpful concept for identifying continuities across regimes of coercion in the labor process, which he argued were widely shared across the post-Reconstruction US South and European colonies in Africa.

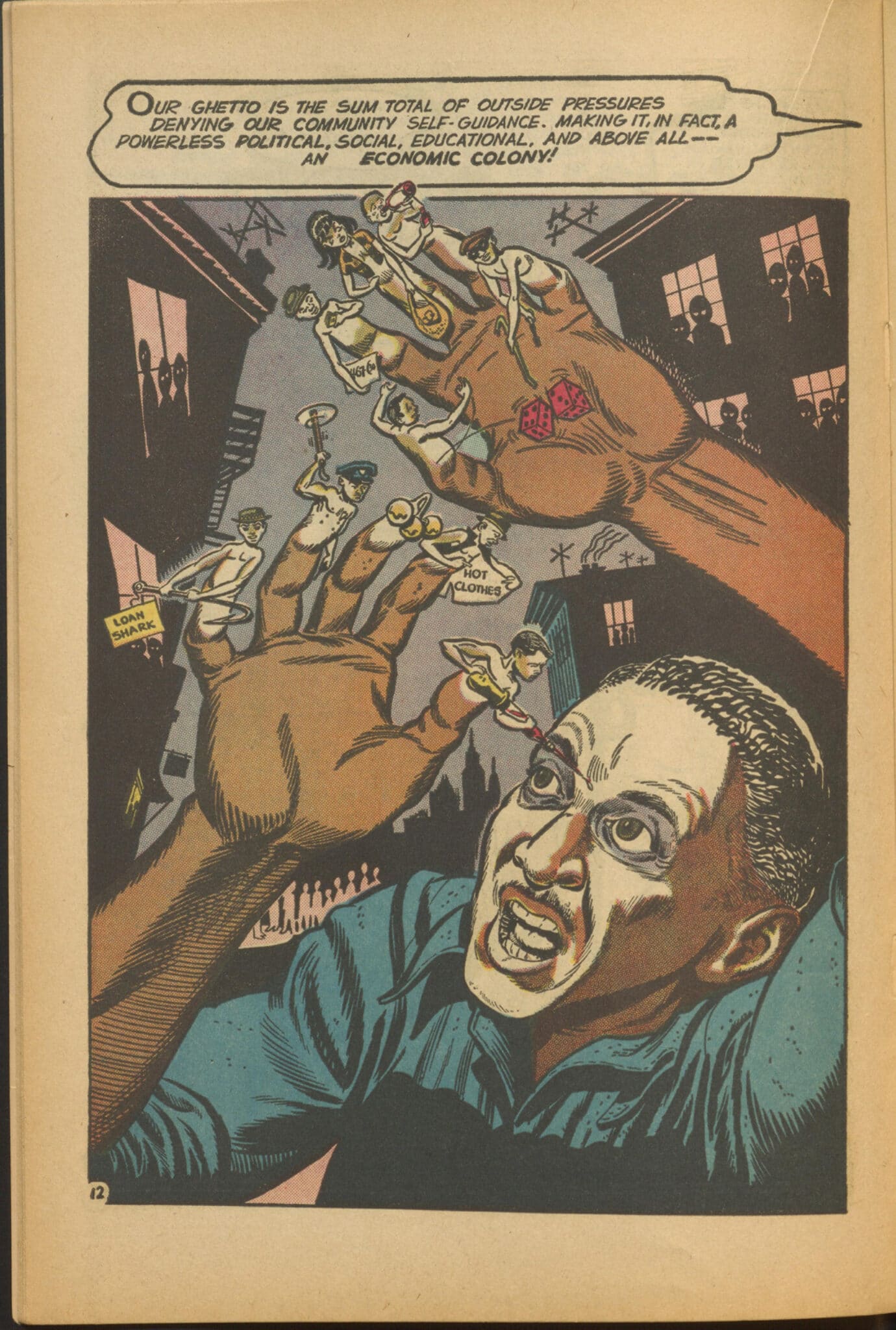

But for others, the language of colonialism provided a means to analyze forms of racialized exploitation that were not strictly tied to the labor process. For example, in the vision of the “ghetto-as-colony” that was formulated first by the liberal Black psychologist Kenneth Clark and then widely adopted in theorizations of internal colonialism by radicals in the Black Power movement, housing and consumer exploitation played a major role. Absentee landlords and absentee business owners (providing a surplus of overpriced, low-quality consumer goods) could prey on Black residents of the ghetto because regimes of housing segregation blocked their exit from these neighborhoods and employment discrimination kept Black workers in low-wage jobs.

Crucially, although a generalized vision of colonialism as a regime of racialized economic exploitation undergirded the politics of colonial comparison, this did not mean that analyses of internal colonialism constituted claims of equivalency across space. For example, the autoworker and Black Power activist James Boggs argued that the underdevelopment of Black America consisted not in arresting industrial development—characteristic of European colonial rule in Africa and Asia—but in accelerating the imposition of a postindustrial condition, defined by the racially uneven impact of automation and the increasing disposability of Black workers under American capitalism.

The role of Haywood and the Comintern is important. The adoption by the Sixth Congress of the Third Communist International (Comintern) of a resolution declaring the “right of the Negroes to national self-determination in the southern states, where the Negroes form a majority of the population,” which Haywood pushed for, helped to link the question of Black self-determination in the United States with the Comintern’s global commitment to the national liberation of colonized peoples. This resolution helped the CPUSA build support among African Americans in the 1930s especially and it is certainly a key moment in the genesis of the concept of internal colonialism.

The concept of internal colonialism really became a keyword in Black political thought in the postwar period, and especially in the Black Power movement in the mid-1960s. Some scholars have seen this as a story of, yes, diffusion from the Comintern outward, but even more as a story of disappearance and reappearance—of thinkers and activists in the 1960s reaching back to an earlier era for a political language that had largely disappeared. But I don’t think that’s correct.

A wider and more diverse set of influences shaped the emergence of internal colonialism as a keyword in postwar Black political thought. For one, during the Second World War both liberal and radical Black thinkers, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke, analyzed the condition of African American oppression as analogous to colonialism, but in ways that were very different from the Comintern’s Black Belt thesis. Of equal importance, during the 1940s and 1950s, African American thinkers were developing distinctive ideas about colonialism that would go on to influence theorizations of internal colonialism. These ideas, which were mobilized in debates about international development in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Gold Coast independence movement, focused on the insufficiency of political sovereignty without economic sovereignty—what I describe as an “anticipatory critique of neocolonialism.”

To be sure, some key figures who developed theorizations of internal colonialism, such as ex-Communist Harold Cruse, clearly drew on Haywood’s work and the idea of self-determination in the Black Belt. But Cruse’s concept of “domestic colonialism,” which he elaborated most fully in his 1962 essay “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American,” also differed from Haywood’s significantly. His vision was not tied to the territory of the Black Belt in the South. And Cruse defined domestic colonialism not in terms of political sovereignty (or lack thereof) but in terms of cultural degradation and racialized exploitation. His definition was further tied to his belief, common on the New Left in the early 1960s, that the industrial working classes of advanced capitalist societies were unlikely to serve as the agents of revolutionary transformation. As he put it, the “revolutionary initiative has passed to the colonial world, and in the United States is passing to the Negro.”

For other influential thinkers who pushed forward conceptions of internal colonialism, such as the liberal psychologist Kenneth Clark, the colonial analogy emerged out of a kind of immanent critique of Great Society liberalism. Clark’s famous description of American ghettoes as “social, political, educational, and—above all—economic colonies” emphasized that urban political economy was the crucial arena of racial domination in American life; it became extremely influential on formulations of the internal colony thesis in the Black Power movement, which Clark himself opposed. (To give just one example, Clark’s words served as the epigraph to Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton’s 1967 book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America.) This line is best-known from Clark’s bestselling 1965 book Dark Ghetto, but Clark had actually written it earlier, in a six-hundred-page social survey he conducted with his community action agency, Harlem Youth Opportunity Unlimited. Clark’s growing frustration with community action, and with the limitations of the policy programs of the War on Poverty, influenced his decision to analyze the political economy of the Black ghetto in colonial terms.

Clark’s case is a good example of why I tell the history of the internal colony concept in relation to other currents of comparative thinking about the US and the decolonizing world. Clark’s disillusionment with community action derived in part from how the architects of the War on Poverty took very different lessons from the unfolding process of decolonization. The American urban crisis was a stage on which competing visions of colonialism and decolonization played out.

The internal colonial analysis did not necessarily point in the direction of a single political program, but it did entail a clear set of political commitments. First, it entailed a rejection of what Aziz Rana calls the “creedal narrative” of American history, or the idea that the nation is defined by the gradual extension of rights and freedoms to those initially denied them.2Aziz Rana, The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document that Fails Them (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226350868.001.0001. Second, it involved a focus on the structural and cultural components of American racial inequality. Third, for almost all of its adopters, it demanded an internationalist commitment to anticolonial struggles outside the United States.

One major reason for its adoption, especially in the middle of the 1960s and after, was the feeling among Black freedom movement activists that the prevailing vocabulary surrounding Black inequality—especially the concept of “second-class citizenship”—failed to capture those commitments. Many framings of the Black freedom movement as a struggle against second-class citizenship—by, for example, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP—seemed to buy into the “creedal narrative,” foreshortening the horizon of the movement to the pursuit of equality before the law and rendering internationalist commitments suspect. Malcolm X explicitly contrasted the two concepts in his 1964 speech, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” suggesting that the language of colonialism underscored the basic injustice of the American constitutional order and promoted opportunities for solidarity with the Third World.

Beneath these commitments, a wide range of demands were formulated. For the Black Panther Party, for a time at least, the concept of internal colonization undergirded their demand for a UN-sponsored plebiscite among Black Americans for the purpose of determining their “political destiny.”

More broadly, though, the colonial analogy framed the demands for economic redistribution articulated by many segments of the Black Power movement. There are innumerable examples of this, but two illustrative ones emerged at the National Black Economic Development Conference, held in 1969 in Detroit. There, the Detroit-based Black Power activist James Boggs called for a series of reforms that linked longstanding socialist aims, such as social housing, with Black nationalist priorities, such as a “land bank” that would enable Black people to become landed proprietors in the South. At the very same conference, James Forman, the former SNCC leader, issued the “Black Manifesto,” which called for reparations to Black Americans funded by white-majority churches and synagogues. Both sets of demands, despite clear programmatic differences, were framed by a colonial analogy—indicating the degree to which the idea of internal colonialism formed a key part of the lingua franca of Black Power politics.

The spread of the analysis of internal colonialism among Black activists in the 1960s opened space for dynamic conversations about the varieties of American colonialism, including the history of Indigenous genocide and dispossession encapsulated in the term “settler colonialism.” For Vine Deloria Jr., the Standing Rock Sioux intellectual and a leading influence on the American Indian Movement (AIM) at this time, the turn by Black Power leaders toward an embrace of “self-determination” presented new opportunities for solidarity among Black and Indigenous peoples in the United States. There were clear episodes of this solidaristic approach, as when the Black Panther Party organized demonstrations to support AIM’s occupation of Wounded Knee.

However, these conversations about the varieties of American colonialism also included misunderstandings and missed opportunities. While Deloria lauded the Black Power movement, his analysis often flattened the longer history of the Black freedom movement, reducing its rich and radical history to a mere demand for inclusion within the settler state. On the other side, certain Black activist formations that embraced the analysis of internal colonialism could overlook key elements of the critique of settler colonialism. The Republic of New Afrika, in the most direct attempt within the Black Power movement to renew Haywood’s Black Belt Thesis, envisioned a sovereign Black nation-state encompassing five states in the US South—a vision at odds with Indigenous claims to sovereignty over the same land.

Across the period I examine, state policymakers were engaged in their own politics of colonial comparison, a politics that responded both indirectly and directly to Black activists’ politics of colonial comparison. Even during the Second World War, high-ranking State Department officials Leo Pasvolsky and Isaiah Bowman were aware that an acknowledgement of “internal colonies” in the United States—and they used that language explicitly—posed a thorny diplomatic problem in their attempts to design a trusteeship system for certain colonies after the war. For these State Department policymakers, who spent the war negotiating with the British over the future of their empire, the fact that racial oppression against African Americans could be seen as an internal analogue to that empire—leaving aside the question of the United States’s own territorial empire, an important issue in its own right—was hardly academic. So, really from the early 1940s onward, rather than a story about cooptation, you have one about competing projects of colonial comparison authored, on the one hand, by liberal policymakers and state actors and, on the other, by Black activists and intellectuals.

By the early 1960s, liberal policymakers and their allies in the nonprofit and academic worlds had gotten used to drawing lines of connection between the colonial/postcolonial world and disadvantaged communities in the United States. A host of excellent scholars have demonstrated conclusively how thoroughly “domestic” social policy in the 1950s and 1960s was imbued with concepts and practices derived from “international” development policy. This was especially true in community action, which, as Daniel Immerwahr has shown in his 2015 book Thinking Small, was modeled on community development programs overseas.3Daniel Immerwahr, Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt13x0h4w.

What was particularly interesting to me, as I looked at this material, was the way this story intersected with Black politics. The Community Action Program (CAP) of the War on Poverty is sometimes romanticized because of the call, written into the legislative text of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, for the “maximum feasible participation” of the poor in the design and implementation of antipoverty programs. But a competing and, I argue, more important imperative in CAP delimited the program’s potential from the beginning: the empowerment of politically moderate leaders in poor communities.

The idea that the success of antipoverty programs depended on “indigenous leadership” in poor communities had its origins in the international development work of Paul Ylvisaker, a Ford Foundation official who designed the earliest community action programs and inspired their uptake in the Johnson administration. Ylvisaker was an urban planner and the originator of the Gray Areas Program in the Ford Foundation, which was the first place the independent community action agency was developed as a means of fighting poverty. His vision of these agencies was based on the idea that they should empower “indigenous leaders” in poor communities who aligned with the aims of the Foundation and the demands of liberal capitalism more broadly—a vision he had forged through a brief foray into international development politics in India. At the very same time, in activist and intellectual circles in Black urban politics, a critique of “social welfare colonialism” emerged in response to these prevailing forms of liberal antipoverty work, which laid the groundwork for more thoroughgoing critiques of metropolitan political economy expressed in a colonial idiom. This conflict, I think, is best understood not as a story of cooptation, but as a story about distinct and incompatible attempts to articulate the significance of decolonization in relation to American politics.

That said, by the late 1960s, there are some clear instances of cooptation of the language of internal colonialism. Once the concept became part of the lingua franca of the Black Power movement, its proliferation—and especially the way it was increasingly linked with the social-scientific paradigm of ethnic group pluralism—made the concept available for more conservative appropriations. The most obvious example of this is when Richard Nixon, in his speech accepting the Republican Party’s nomination for President in 1968, defends his plans to scale back the War on Poverty by arguing that African Americans “don’t want to be a colony in a nation.” Nixon’s “Black capitalism” programs had some support from conservative elements in the Black Power movement, especially Roy Innis and Floyd McKissick, then the leaders of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). And, clearly, Nixon was attempting to build support for these programs by appropriating a concept that held a lot of purchase in the Black Power movement at that time.

Territoriality was an inescapable question for Black thinkers and activists who invoked the concept of internal colonialism. For Haywood and those who endorsed the Black Belt Thesis in the first half of the twentieth century, the land base for an African American national liberation struggle would naturally have to be in the South. But the Great Migration and the formation of an urban Black working class in the cities of the North, Midwest, and West complicated this view. The politics of colonial comparison took on a more urbanized character for Black thinkers and activists during the 1940s and afterward. St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton, in their magisterial 1945 work of urban sociology Black Metropolis, framed their ethnographic analysis of Black life in the Bronzeville neighborhood in Chicago in relation to movements against colonialism around the world.

In the 1960s, when the concept of internal colonialism begins to be embraced more widely across Black thought and politics, the question of territoriality remained important, but largely in relation to the territorial specificity of the Black ghetto. Most of the figures responsible for the concept’s growing popularity in the 1960s—such as Harold Cruse, Kenneth Clark, James and Grace Lee Boggs—were themselves residents of northern cities. In that context, it no longer made sense to couple references to land to demands for national sovereignty, as Haywood had done. For the Boggses, who coauthored an article entitled “The City Is the Black Man’s Land” in 1965, in addition to greater Black political power at the metropolitan level, the urban character of Black working-class life demanded forms of economic redistribution at the national level that would reverse the persistent disempowerment of predominantly Black cities that operated through US federalism, tax policy, and the like.

But issues of territory and scale were also dividing lines among those who invoked the colonial analogy in the 1960s and early 1970s. For Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton, the increasingly deterritorialized nature of American capitalism in an era of globalization was a reason to abandon the concept of internal colonialism altogether. To Newton, the fact that the American empire no longer depended on forms of territory to exercise control demanded a new geographic imagination, which Newton called intercommunalism: a vision of an archipelago of struggle of discrete communities against a technologically advanced, globally hegemonic superpower. The inability to resolve these territorial questions, or come to a consensus about them, was a major reason for the decreasing purchase of the concept of internal colonialism in Black activist circles by the mid-1970s.

I cannot stop thinking about the moment when, at last summer’s Democratic National Convention, attendees of the convention literally covered their ears as they walked by people protesting the genocide in Gaza and the Democratic Party’s role in perpetrating it. To me, this is a metonym for contemporary US liberalism, which insists that, in order to oppose the authoritarian right, we must keep domestic issues separate from international issues.

This is not only an ethical failure, but a political and strategic mistake. Undemocratic rule, state violence, and economic exploitation “abroad” do not exist in some separate realm from how these forces operate “at home.” As many activists have pointed out, we can see these continuities in the militarization of police, in the crises of austerity doled out to Black neighborhoods of debt-ridden American cities and to debt-ridden nations of the Global South alike, and in many other arenas of contemporary life. We need a political vocabulary that helps people understand these connections—that helps us see the domestic in light of the international. My modest hopes for my book are that it might give readers a sense of how a previous generation constructed such a vocabulary (with all its promises and pitfalls), and that activists might find resources within the history I recount for such a task today.